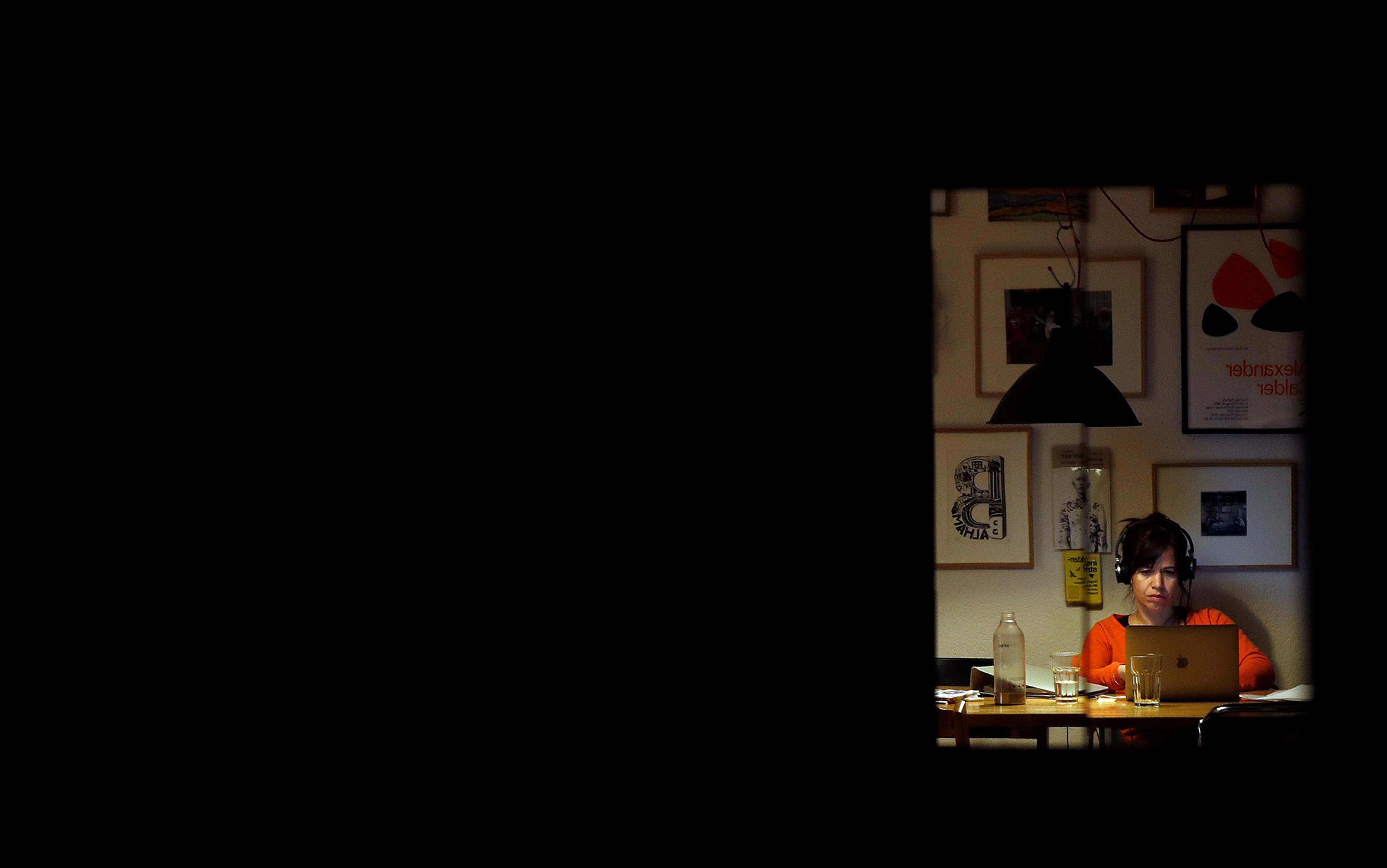

Adrienne Boyle, one of Britain’s most important flexible-work activists of the past century, gazed out the window of her houseboat in Dublin’s historic docklands district. She had a clear view of Google’s 14-storey European headquarters. ‘There’s not much flexible working in that one! Lights on all night, 11pm Saturday night,’ she told me, when I spoke to her in December 2017. ‘It’s flexible all right, but you’re working 60-hour weeks.’

Long before the 2020 pandemic made remote work a necessity, employees across Anglo-America said that they wanted more flexibility about where and when they work. A 2017 Gallup poll in the United States found that 51 per cent of workers would be willing to change jobs for one that allowed them some control over their hours, and 35 per cent for one in which the location was flexible. While flexibility was originally associated with women seeking to combine paid work with unpaid childcare, it’s since become a key item on the list of desirable perks for all workers. In the 21st century, flexible work culture has found its apogee in large tech companies that have embraced notions such as work-life balance, family-friendliness and employee wellness as guiding principles.

Yet even those employees who enjoy the benefits of flexibility – and it’s still a privileged minority – have found that it doesn’t necessarily mean their working lives have become easier or better. Flexibility can make it hard to draw boundaries around paid employment, and difficult to disaggregate work from the rest of the day. Nor has flexibility at work solved the pressing problems of child or eldercare, or shifted the gendered division of housework. While companies such as Google and Facebook like to trumpet their employee benefits, they still haven’t fixed the childcare problems of staff, and they still fail to make their benefits accessible to everyone. The abrupt restructuring of daily working life for tens of millions due to the COVID-19 pandemic has also dramatised just how different ‘flexible’ work is in different contexts: liberating for some, imprisoning for others.

Modern-day flexible work policies didn’t arise in a sudden moment of crisis, but from the slow burn of second-wave feminist activism. In the 1970s, even though growing numbers of women had entered the paid workforce, they continued to do a disproportionate share of the childcare and housework. In the consciousness-raising and campaign groups that cropped up in the US and Europe, women increasingly recognised that what felt ‘merely’ personal was, in fact, political. A new generation of activists pushed for changes in the structure and conditions of paid work. The idea was to render it more suited to the needs of workers with caring responsibilities and allow women of all backgrounds to participate in the economy on equal terms with men. Meanwhile, men would be urged to share more fully in maintaining home and family. Feminist activism for what we now call ‘flexibility’ was part of a vision for remaking communities and supporting the needs of workers as whole human beings. This is most apparent in the first-hand testimony of the women who dedicated their energies to reimagining paid work at a time when the 9-to-5, 40-hour working week was the near-universal model for professional success.

In the decades since feminists first challenged the structures governing paid work, the vision at the heart of their campaigning has been lost. While employers have adopted some feminist ideas for reforming the workplace, for the most part they’ve strategically bracketed the question of who ends up looking after the children. Ironically, piggybacking on feminists’ ideas about transforming paid work has done more to contribute to a 24/7 work culture than it has to opening up new options for women. Only by looking back at the earlier ideals that structured flexible employment policies can we recover a richer sense of what it might mean to imagine a future that works for us all.

Born in 1946, Boyle is one of eight children in a working-class family in inner-city Dublin. By the late 1970s, she had become involved in a range of radical activities in London, where she’d come to study. When she completed a community work qualification in 1977, she was a single parent, and looking for part-time employment. But she couldn’t find any, and faced the reality of taking on unskilled work.

Within the year, Boyle was meeting regularly with a small group of women in the front room of her housing co-op to think through what could be done. Inspired by an organisation called New Ways to Work in San Francisco, they formed the Job Sharing Project to advocate for allowing two people to formally divide a full-time position.

This was all unfolding in the crucible of the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, as women in the US and Europe pushed for fundamental reforms to relationships – intimate, professional and political. Some unions and employers in the US and Britain had toyed with flexible work in the 1960s, as a way of allowing professional women to remain in the paid workforce after having children. By the mid-1970s, research emerging from the European Economic Community suggested that flexible hours was the single measure most likely to improve women’s professional opportunities. Meanwhile, a new tide of grassroots social pressure for women’s rights was sweeping both Europe and the US. It was in this context that feminist activists first explicitly connected flexible work practices to the hope for a more equal society.

The 9-to-5 working week accommodated most men just fine but was inherently at odds with providing childcare

The postwar expansion of higher education created a large cohort of women with professional training and new aspirations to pursue fulfilling careers. By the 1970s, rising costs of living and wage stagnation meant that a single male-breadwinner income was becoming insufficient to support a whole family, and ever more women started jobs in order to make ends meet. Between 1951 and 1971, the percentage of married women who were in the workforce went from 22 to 42 per cent. This only continued to increase in the 1980s and beyond. By 1989, among two-parent families, 57 per cent were dual-income.

As women came together in activist groups, they reflected on the struggle of combining paid work with care work – what was named ‘the second shift’. Over the course of the 1970s and ’80s, feminists advocated for the introduction of flexible hours, for telecommuting, and for ideas such as ‘term-time working’ and ‘job sharing’. They hoped that these new policies would increase equality in employment opportunities for women, overturn the gendered division of labour at home, and challenge traditional views about paid work.

The programme was at once pragmatic and utopian. The idea was to open up part-time employment in a theoretically limitless range of professions. Job sharing would mean fewer hours and the chance for mothers to remain in paid work without a loss of benefits or status. At the same time, it would challenge the hegemony of what activists saw as a 9-to-5, 40-hour working week – which accommodated most men just fine but was inherently at odds with providing childcare.

While advocates of job sharing were largely white, middle-class women with higher education, they knew that job sharing couldn’t be a panacea for all workers – above all those who needed a full income. But the idea reflected the utopian conviction that job sharing would encode work, and by extension society, with an entirely new set of values. Job sharers could not be ‘egotistical or possessive’, as Pam Walton, a city planner and early job-sharing activist, put it – their responsibilities would demand teamwork and downplayed egos. Job sharing favoured what were traditionally seen as ‘feminine’ values such as collaboration, listening and sharing. It also promised to be what Boyle and Walton termed a ‘more social way of working’. Activists imagined that remaking work culture would transform work for all.

In addition to pushing for reforms to the structure of paid work, feminists campaigned for workplace nurseries. As the postwar British state scaled back its support for childcare, growing numbers of working mothers found themselves in a bind. Feminist groups such as the National Child Care Campaign continued to demand state-backed childcare throughout the 1980s, but many activists had resigned themselves to the reality of more minimal social provision. Instead, they began to turn to employers to provide solutions. This was also the case in the US, where a less comprehensive welfare state meant that activists were accustomed to petitioning the private sector for benefits.

Feminists pushed for nurseries in a wide range of workplaces, from universities to grocery stores. These campaigns recognised that flexibility alone wasn’t enough – particularly for those who wanted or needed to work full-time, or were on low wages. In 1970, Pam Calder, a psychology lecturer at London South Bank Polytechnic, campaigned for a workplace nursery. Although ultimately successful, it took five years to get off the ground, during which Calder struggled to secure reliable childcare. On the day she was due to return to work, when her daughter was three months old, the registered childminder she’d arranged was nowhere to be found. In desperation, Calder left her with a kind neighbour. The arrangement lasted, but this childcare solution was ‘not something that you can rely on as a system’.

Whether in favour of employer-led or community childcare, activists were motivated by a shared vision – a belief that childcare services should be available to all; should bring together diverse groups locally; and shouldn’t be provided by low-income women of colour for the exclusive benefit of middle-class white women. This vision included the hope that childcare and early education would be anti-racist and anti-sexist in its content.

While first introduced with women in mind, they eventually expanded to include workers of both sexes

In practice, using childcare as a vehicle of equality was a tall order in communities and workplaces alike, and white activists didn’t always recognise or address the unique barriers for Black families. Well into the mid-1980s, Black childcare activists highlighted these tensions. In 1985, members of a Black advocacy group within the National Child Care Campaign expressed their feeling that ‘the NCCC is a white organisation and doesn’t appear to think about how other people raise children differently’.

Despite the challenges of building a broad-based feminist movement, by the 1980s feminist campaigns to remake work had gained some traction – particularly in the public sector. In both the US and Britain, employers ranging from school districts to local government councils introduced job-sharing policies. While first introduced with women in mind, they eventually expanded to include workers of both sexes. The London Borough of Camden led the way by introducing extensive parental and family leave, an official job-sharing scheme open to all staff regardless of sex or paygrade, and an onsite childcare centre. The council worked tirelessly, if not always successfully, to see that the opening hours catered to the needs of its workers, and that staff of all income levels and backgrounds could use it. It was these policies, rather than flexible hours or locations, that activists believed were likely to foster a healthier work culture.

Well into the 1990s, feminists in the workplace presented flexibility about hours and location as just two of a number of benefits needed to support workers as human beings with lives and responsibilities beyond those furnished (and depleted) by capitalism. In 1999, the Leeds Animation Workshop – a British feminist film collective – released the film Working with Care that featured the fairytale story of a queen and her staff. As a benevolent ruler, she guaranteed all royal staff not just flexibility regarding hours and work locations, but also access to onsite child and elder care, a company laundry, cafeteria, gym, massage centre and union office. The workplace resembled a town with the needs of its community firmly at its centre.

Beyond progressive pockets of the public sector, the history of evolving Anglo-American employment practices was a rather different one. Public sector policies to support the needs of workers with caring responsibilities were made possible by the largesse of postwar economic growth. But over the 1980s, economic stagnation and cuts to the public sector ensured that progressive workplace innovations largely fizzled out.

It was now the private sector that took up the baton of structural workplace reform. Major American and British companies ranging from American Express and Rank Xerox to the NatWest bank and Sainsbury’s supermarket implemented so-called ‘family friendly’ policies for the first time. In under a decade, private companies had begun to actively compete with one another to be perceived as having the best benefits for workers with families. But what looked at first glance like a resounding feminist victory was, in practice, a pared-down compromise.

The private sector’s openness to rethinking women’s work was far from automatic. Rather, it depended on the tireless, concerted efforts of feminists pursuing organisational change. In 1978, the academic Margery Povall received funding from the German Marshall Fund of the US for a project to stimulate affirmative action for women in Europe. She spent a year embedded at NatWest in Britain. There, Povall tried to push back against the assumption that women always wished to stay at home once they’d had children, and emphasised what the bank itself would gain by retaining trained female employees. But she faced an uphill battle with company managers.

It took her a long time, Povall told me in an interview, to see that ‘these men didn’t realise what a married career woman was’. She frequently found the process exhausting and depressing, yet it was also galvanising: ‘Interviewing managers turned me into a feminist.’ By 1981, Povall had persuaded the bank to introduce one of the first maternity-leave returners schemes in the UK. But her further recommendations – including flexible hours, onsite childcare and parental leave for men and women – made little headway.

Nonetheless, feminists redoubled their efforts to engage with the private sector. As many activists struggled to keep afloat financially, working with the private sector also presented advantages. What started life as explicitly Left-political activist groups – including the Job Sharing Project – reconstituted as politically neutral non-profits. In 1980, the Job Sharing Project took the name New Ways to Work, in parallel with the US organisation that had inspired it, and transformed into a consulting body that worked with the private sector. While trying to remain connected to their political vision, feminist charities such as New Ways to Work sought to capitalise on the sustainability and credibility engendered by the 1980s boom in business consulting.

Activists had long suffered from a blind spot when it came to the realities confronting low-income women

At the same time, private-sector employers in Britain were growing nervous about demographic shifts that would lead to a declining pool of traditional recruits. Policymakers began to talk about a ‘demographic time bomb’, the result of the sharp birthrate fall in the late 1970s on the tails of the growing availability of birth control and the legalisation of abortion. The worry was that, by the mid-1990s, this would produce a precipitous decline in school-leavers entering the labour market. As a consequence, the need to recruit and retain female staff assumed a degree of urgency. Progressives seized this opportunity to advance feminist ideas about restructuring paid work – but, crucially, they also absorbed some of the private sector’s own interests and ways of framing the problems.

In their collaboration with businesses, activists started to shift their focus from utopian ideas about job sharing and mothers’ needs to the benefits of flexibility and the needs of workers generally. By framing demands in terms of the needs of both male and female workers, activists could push back against the trivialisation of the flexible-work agenda. This allowed them to overcome many of the obstacles Povall had faced a decade earlier, and to shape a new ‘business case’ for flexibility. Yet activists walked a fine line between appealing to the corporate bottom line and maintaining an explicitly feminist agenda. Flexible-work activists had long suffered from a blind spot when it came to the realities confronting low-income women – a myopia that was only exacerbated by the private sector’s near-exclusive concern with retaining the most highly paid, skilled women staff.

Companies soon discovered that flexibility, along with basic maternity leave and provisions for returning to work after a baby, served their own financial interests. Greater flexibility about when and where white-collar workers did their jobs didn’t noticeably affect staff productivity, quality or efficiency. At the same time, flexible policies allowed companies to portray themselves as ‘progressive’, and so to appeal to the increasingly economically significant group of professional women workers. It’s telling that the same organisations that were enthusiastic about the introduction of flexible work nonetheless tended to reject onsite childcare. A handful of companies did create nurseries for staff from the late 1980s, but this was the exception to the rule. The vast majority rejected it as simply too expensive; instead, they followed the lead of American Express, and set up childcare information services for parents. These involved directing parents to resources, but otherwise outsourced all responsibility to the families themselves.

Nonetheless, many private sector companies began disseminating a triumphant narrative of healthy, happy workers in appealing, accommodating environments. To some degree, feminist organisations facilitated this image. Beginning in 1990, the Working Mothers’ Association – a charitable advocacy group for the interests of working parents – began to host competitions for Employer of the Year, designed to ‘encourage employers to adapt corporate culture to fit in with the needs of working parents’. These publicity events cast a spotlight on organisational change, yet the vast majority of working families were left with few, if any, new benefits or forms of tangible support, even as the number of dual-income households continued to climb.

The rationale that guided the corporate embrace of new employment policies was largely detached from feminist visions for a more equal society. It’s unsurprising, then, that the private sector embraced feminist ideas and language selectively. Yet it wasn’t the case that feminism was simply eaten alive by a new corporate capitalist culture; rather, feminist activists and organisations actively worked in and through the private sector to shape what became the status quo. If new policies weren’t everything that activists had hoped, the introduction of some kind of flexibility felt like a step in the right direction.

Over the past 40 years, flexibility has allowed some, primarily white, middle-class workers to have greater control over their working lives. It’s had transformative effects for professional women in particular. The need for parental leave and other forms of support for workers with family responsibilities is now well-established in both the UK and the US, if not yet in organisational practice.

But now that we’re squarely in the 21st century, perhaps we’re finally turning a corner, and recognising that flexibility alone isn’t an adequate wellbeing safeguard. For one, the blindness of the original feminist flexible work campaigns to the needs of low-income workers and their families has become more glaring than ever. For shift workers who are required to work flexible hours in the service sector, it’s stable scheduling, not greater flexibility, that’s most needed. As the 2020 pandemic has shown, working from home, or with flexible hours, isn’t always possible or necessarily even desirable. Women still end up bearing the bulk of the care burden. A wider rethinking of work and its place in our lives is overdue.

Since the turn of the 21st century, theorists and decision-makers tend to reflect on the tension between work and family through the lens of ‘work-life balance’. For Boyle, the concept seems very middle-class and not particularly radical. As she told me from her boat, pointing at those beavering away in Google’s offices: ‘They shouldn’t be working long hours and then be so exhausted that they can’t go and enjoy other things.’

Moving forward arguably requires a new language that isn’t centred on mothers, or parents, or even family-friendliness or work-life balance. What ties communities together isn’t employment but, first and foremost, the bonds of care. The future of work must involve a reckoning with our collective responsibility for and to our children, as well as the elderly, the sick and other vulnerable but vital members of our society. Moreover, it must be a vision that grasps these responsibilities not solely in terms of labour but as encompassing a range of human values.