In the summer of 1999, with nowhere to go between my second and third year in college, I decided to stay with my sister who was living with a couple of roommates in an apartment in Berkeley, California. Soon, I was fortunate to land a summer internship at the San Francisco office of Amnesty International, then located just across the bay in the city’s downtown.

The internship was unpaid, and my student visa barred me from getting a paid job. To earn my keep – or, more modestly, my next lunch – I often went straight to the campus of the University of California, Berkeley after work to be a subject in psychology experiments. Labs would pay $15 in cash for filling out a survey, or $20 if they had to clamp down my fingers with electrical sensors before displaying images on a screen. I would have bought a ticket for the chance to see what labs at a vaunted university were doing behind secured doors, but instead they were paying me for it.

To get to San Francisco, I joined in the daily ritual of the commuting masses on BART (the Bay Area Rapid Transit system), the morning solemnity interspersed with outbursts of underground performances and conductor announcements. But a few weeks into my internship, I heard about an intriguing alternative to BART: the Berkeley carpool, a free ride.

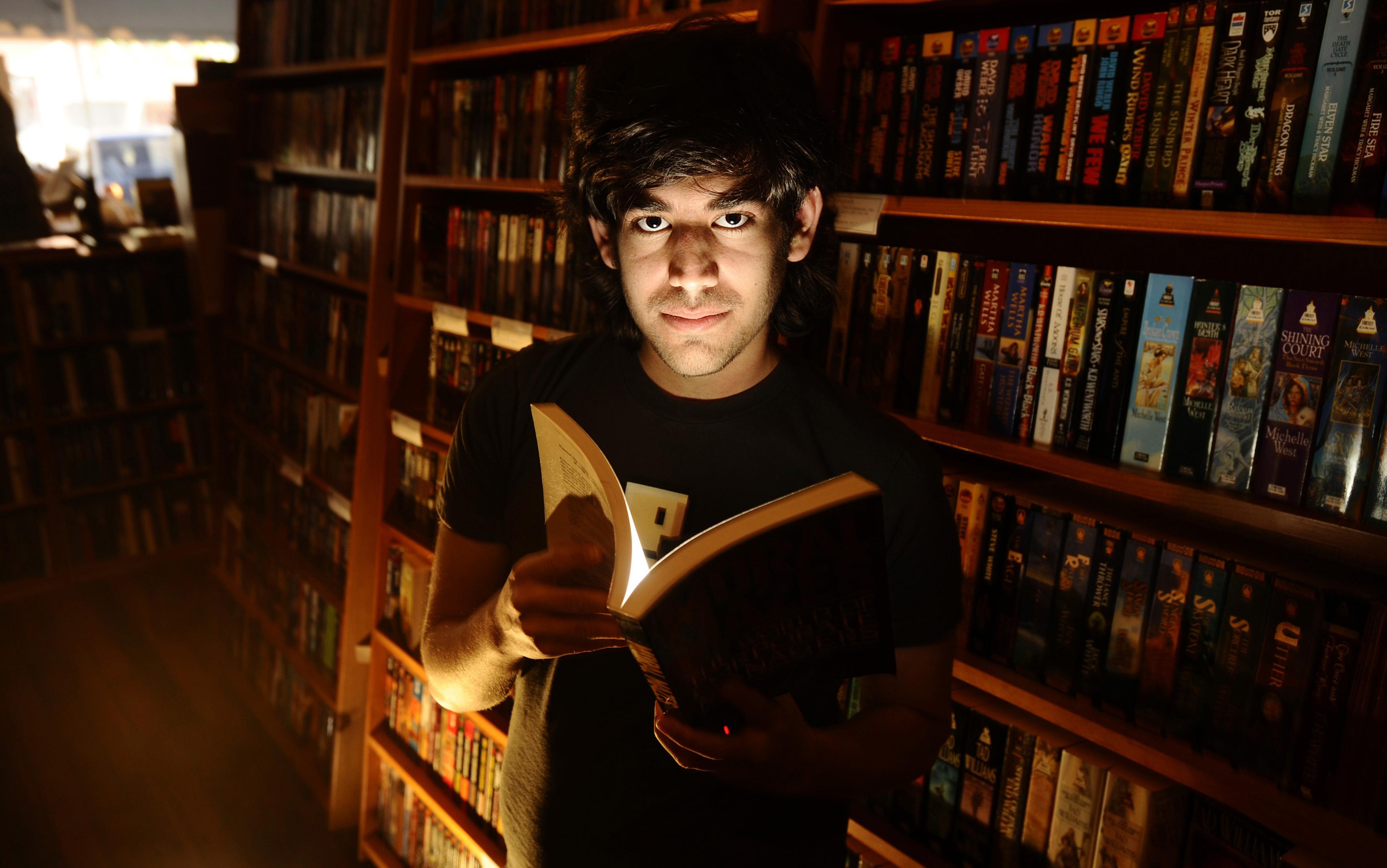

Photo by Damien Maloney

This was before Google, so the only way to find out how carpooling worked was to show up. Here’s what I discovered: you walk to a designated spot – a quiet residential street in North Berkeley – during the regular morning commuting hour. There, you’d find a tidy line of people on the sidewalk, and alongside it a lineup of cars by the curb. There are no signs, no instructions. One by one, a person gets into a car at the front of the line and the car takes off; the line keeps moving as more people and cars replenish it at the back. Everything moves along swiftly. When it’s your turn, you get in the first car in line – no swapping spots, you get what you get – and greet the driver. There are two destination options, both in the heart of San Francisco, and you tell the driver which one you’re headed to.

Then it’s a 20-minute ride across the Bay Bridge, past Treasure Island and into San Francisco, with glimpses of the bay, the sky and the downtown. The genius of this system was that, while the rider got a free ride, the driver got reduced highway tolls and a faster ride into the city for taking in a passenger and using the express carpool lane during rush hour. It enabled a true win-win situation for the two parties, with an extra win for the environment, to the extent that it reduced the number of cars on the road. It worked beautifully.

There was an implicit norm, I soon learned: you did not make conversation with the driver, and the driver did not make conversation with you. Almost without exception, these rides were quiet ones, focused on getting from here to there. This served me just fine; I didn’t care much for small talk at 8 am, not before my morning coffee. Nevertheless, it was a constant source of wonderment that total strangers could reliably give me rides to work, only to be never seen again. There was a potential for a story to emerge if a pair decided to converse, but for me the rides were the story.

I’d play a mental game of luck: joining the line, I’d count the number of people in front of me, then count up to the car that would be my ride. Would this be my lucky day? The luckiest day – grant that I was 20 – was a ride in a sparkling Jaguar. The unluckiest I ever got was being covered in cat hair in a vehicle that was likely better off decommissioned, which was not so bad, all things considered.

Photo by Damien Maloney

A decade later as a graduate student, I read the Yale social scientist James C Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed (2009) when it was first published, along with other works of anarchist history. Scott’s works revolutionised my thinking about authority and human agency. This was every bit the intention of Scott’s writing – to go against the grain of pervasive statism that underlies conventional notions of justice, good governance and social progress. In studying remote communities in Southeast Asia’s hinterlands, The Art of Not Being Governed offers analysis aimed at inverting our priors: where we might observe economic underdevelopment in the rural hills, Scott saw zones of relative autonomy from the state – a successful ‘evasion of subject status’. Where we might note high rates of illiteracy, held universally to be a social deficiency, Scott saw a deliberate safeguarding of oral traditions over generations – an act of ‘cultural refusal’. These communities’ rebuffing of written text was also strategic, as written histories risked exposing themselves to state authorities; illiteracy, then, was an ‘active choice’ made by the hill people in a state-centric world run by ‘text-based’ rulers.

Scott suggests we withhold our pity: while those living within the reaches of the state toiled under systems of taxation, conscription and servitude to state interests, the seemingly ‘uncivilised’ populations of the rural hills achieved a ‘purposeful statelessness’ that kept them free from all of the above. Scott’s scholarship does not ask us to buy these arguments wholesale so much as it pushes us to reconsider what the state stands for and how much agency our bases of knowledge afford to ordinary people as they navigate structures of power, whether in upland Southeast Asia or elsewhere. It asks us to do the hard work of continual questioning.

A few years later, as a professor of international relations, I included a segment on anarchism in one of my courses. This was the era of expansive state-building in Iraq and Afghanistan; soldiers and technocrats swooped in from abroad to install a new government designed by foreign officials, and sought to ram in the projects amid violent insurgencies jeopardising their plans. Though written in other contexts, Scott’s works served as a clarion call for a radically different approach. In Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998), Scott reminded us of the deep reserve of knowledge people held, organically, about their own communities, cultures and organisational systems, and urged healthy scepticism toward outsiders’ ability to prescribe solutions ‘from above’. When students invariably asked: ‘So what should the US do?’ in response to US-led foreign regime change run terribly amok, I used Scott to probe whether that was always the right question to ask – didn’t it preclude broader possibilities and voices? What alternatives can be envisioned? We discussed what Scott termed ‘high-modernist designs’ introduced by detached experts and their disregard for local knowledge, and the resulting mismatch between scientific ideals and reality. One could almost believe Scott was writing specifically about US foreign policy in the counterterrorism age, making his case against the imposition of grand, decontextualised, ahistorical social engineering projects that discounted those for whom the plans were ostensibly drawn – the people.

Everyday forms of nonviolent resistance can be carried out in many smaller but no less powerful ways

Anarchism has no single definition. Scott’s anarchism is not of the window-smashing anti-capitalist variety, nor is it a promotion of a Marxist utopia. It does not require people to live in communes and grow their own food, nor does it suggest an armed uprising to topple regimes. It is not even anti-statist per se, as Scott holds that the state ‘is the ground of both our freedoms and our unfreedoms’. Scott’s anarchism is one that allows me to embrace his scholarship while simultaneously, without intellectual incongruity, making a career of educating aspiring diplomats and civil servants and submitting my own child to public education, seen in other corners of anarchism as a bastion of statist propaganda.

Scott’s anarchism is, rather, a way of seeing the world, a ‘sensibility’ as he calls it, one that can be honed the way a bird watcher can train herself to hear the calls of a particular species, or a cook can learn to detect the early scent of a good char. It is not anti-statist but anti-oppression, pro-human and proactive. It is about noticing taken-for-granted social designs and erecting creative defences against powers and arrangements that chip away at one’s ability to exercise self-ownership. It is Scott following his ‘rational convictions’ and choosing to jaywalk when everyone else waited patiently for the light to turn at an intersection free of vehicle traffic. It is people’s feet forming the most direct and well-trodden path across a park’s lawn – known as ‘desire paths’ – in defiance of urban planners’ aesthetic inclinations. It is the city of Houston, where I live, declaring itself a ‘book sanctuary’ and ensuring its public libraries carried titles banned in schools, thus rendering state-imposed book bans de jure effected but de facto nullified in an unequivocal pushback against censorship.

The path of desire. Photo by Duncan Rawlinson/Flickr

Throughout history, communities have demonstrated a tremendous ability to think for themselves and, more than that, to resist, in an entirely pragmatic fashion, forces of domination and devise alternatives that help restore their agency. Scott’s anarchism is in this sense manifestly anti-authoritarian. There is a clear theme of subversion running through his scholarship. But what he brings to light, in particular in Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (1985), is people’s ability to carry out ‘petty acts of insubordination’ and acts of ‘quiet evasion’ against exploitative and repressive powers, the very opposite of violent revolts in the spectrum of resistance. Collective civil disobedience and mass protests are somewhat close cousins, but Scott insists that subtler, everyday forms of nonviolent resistance against domination can be found, and carried out, in many smaller but no less powerful ways. They may not always work, but when they do the result is a restoration of individuals’ sense of dignity.

Of the numerous examples of what it means to approach the world with an anarchist sensibility, I liked to use one that Scott offers in Two Cheers for Anarchism (2012): the contrast he draws between the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Iwo Jima Memorial, both located in the Washington, DC area. The Vietnam memorial is minimalist in its design: two black granite walls stretch across a lawn and meet to form a wide angle; they are engraved with the names – staggeringly numerous – of fallen US service members. The names are not listed alphabetically or by military rank, but chronologically in the order in which they fell. The memorial has no other adornments and makes no overt political claims. Rather, for Scott, ‘a great part of the memorial’s symbolic power is its capacity to honour the dead with an openness that allows all visitors to impress on it their own unique meanings, their own histories, their own memories.’ Those who lost a loved one will find the name they seek amid the multitude, then they might run their fingers over the engraved name, put a paper and pencil to it to make a rubbing, or leave mementos by the wall. The monument invites visitors to participate in meaning-making; it does not itself offer it. And, in so doing, it leaves room for as varied a view of the war and its legacies as is held by the public.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Photo by Howard Ignatius/Flickr

In contrast, the Iwo Jima Memorial (officially, the US Marine Corps War Memorial) is ‘manifestly heroic’, consisting of a colossal sculpture of a group of Marines raising the US flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima in Japan in the Second World War. It captures a moment of military victory gained at a great cost in lives. For Scott, it is not surprising that the memorial is ‘monumental and explicit’ given the ‘virtual unanimity with which that war is viewed in the United States’. Yet, Scott suggests that the effect of the dramatic display is to foreclose the kind of reflection, participation and questioning the Vietnam memorial inspires; the Iwo Jima memorial is ‘symbolically self-sufficient’ if not ‘canned’. Visitors can ‘stand in awe’ and thus receive its message; they do not complete it.

Iwo Jima Memorial. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

This visually striking juxtaposition served well as an illustration of the anarchist sensibility. But as I taught it, I began to see that instruction of Scott’s ideas must itself hew to his anarchist principles to do his works any real justice. There was a fine line to tread between teaching Scott’s text and distilling the true spirit of his works, and intoning that Scott’s compelling commentary embodied the one true anarchist interpretation of the memorials, extolling one as artful while critiquing the other as patronising.

A true anarchist interpretation would grant that anyone who could appreciate the simple straight lines of the Vietnam memorial’s stone walls could also meaningfully reflect on the politics, triumphs and tragedy of the Battle of Iwo Jima despite – or perhaps because of – the ‘heroic’ display. Adopting an anarchist sensibility requires that one puts due faith in the ability of ordinary people to think for themselves, for their own betterment and the betterment of their communities. In his works, Scott – who died this summer, aged 87 – gives all the agency to people, turning our understanding of power upside down. People see through the machinations of authorities. They may not always push back given the risks, but they know they have a cache of capability to evade or thwart projects of manipulation and extraction.

To extend this line of thinking is to presume that ordinary people who come to view an evocative monument can question its overt message and will do so if curiosity leads. Given the battle in the Pacific War is perhaps the lesser known and the more distant in time, the vivid sculpture might in fact do more to inspire visitors to further learn about the war, and ultimately the horror of all wars, than might a less expressive one. Fundamentally, an anarchist sensibility would be open – the theme of this particular section of Scott’s book – to that possibility, and would thus give two cheers for the diversity of forms of public memorialisation that the nation’s capital offers.

In reading Scott’s text with students, I learned anew how teaching, too, can reflect the ethos of the Vietnam memorial as Scott saw it: egalitarian, open and participatory, with a preference not for parsimony over loud claims but critical thought and experience over intellectual hierarchies.

After all, if every war memorial looked like the Vietnam memorial, it would surely be a sight of authoritarian dystopia.

Had the carpool’s norms been codified, enforced with the threat of punishment for infractions?

And that’s when I recalled those summer mornings riding in strangers’ cars across the San Francisco Bay. I reflected, nearly two decades later, on the operational attributes of the Berkeley carpool. No one organised the carpool; it arose from within the community to meet people’s needs in the face of rush-hour traffic, highway tolls and commuter costs. There were no written rules; codes of conduct were implicit and shared through quotidian practice. A programme without formality, an establishment without walls – an institution of the most durable kind, as social science theories taught us. It worked, and all participants benefited.

I thought this illustration from our everyday lives would encourage students to seek out their own. Like looking up an old friend long out of touch, I searched online with some trepidation for information on the Berkeley carpool. Was it still around? Had some municipal office taken over its management and logistics? Had the norms been codified, enforced with the threat of punishment for infractions? Do these sorts of community projects, operating on nothing more than mutual trust and collective benefit, even exist anymore?

And there it was: the same system, intact after decades, its existence merely more visible in the digital age. ‘Casual carpool started 30+ years ago and has been community driven since its origin,’ the minimalist website states. ‘Everyone who participates in casual carpool benefits from using the system, therefore they have an incentive to treat other users respectfully and to promote safety in order to maintain the integrity of the system.’ All of its essential features remained unaltered. Still no rules, just some ‘etiquette’ guidelines: ‘Be friendly with other riders but know when they’re looking for a quiet ride … Don’t jump ahead of others, these lines move pretty quick.’

I read the final lines of its FAQs with a sense of redemption and reclamation: of a youthful memory, of a community’s capacity for problem-solving and self-organisation, and above all of the endurance of social trust amid the daily onslaught of headlines pointing towards its disintegration:

Q: Who runs casual carpool? Who maintains this site?

A: The short answer is, everyone who participates in it plays a role in running it (it’s community driven). Due to this, no specific individual has authority over it (and probably shouldn’t).

I half suspect the website’s text was written by a Bay Area college grad well versed in anarchist theory. And carpooling is no longer so arcane; similar programmes operate in other cities now. Regardless, I gave my own two cheers – for the unexpected convergence of a scholarly argument and its empirical manifestation, a critical reading and openness in a classroom leading, as ever, to discovery.