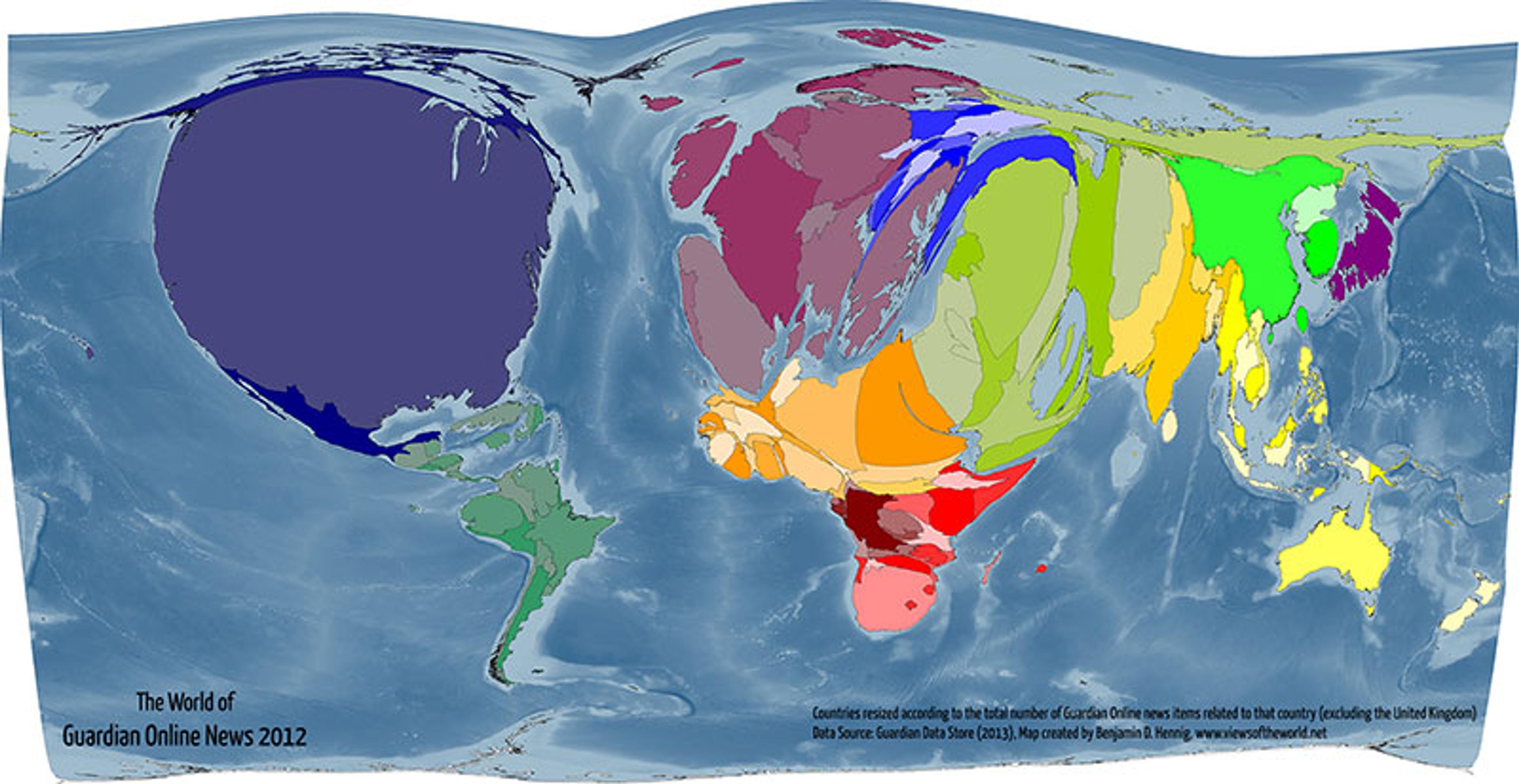

In 2013, the German geographer Benjamin Hennig produced a series of maps depicting the size of countries in terms of the number of articles about them in The Guardian in any particular year. The maps depicted a swollen, obese United States, an emaciated Latin America, massively enlarged European countries, and shockingly small African and Asian ones. The Arab Middle East, however, loomed large and, despite the uprisings and civil wars throughout the region, Israel was among the largest.

Courtesy Benjamin Hennig/Worldmapper

Hennig has not produced more recent iterations of this map, but it’s safe to say that Israel would feature at least as prominently, if not more so, if the map were released today. Why does Israel attract so much attention, and, even more important, why does it elicit such passion? Even now, when Israeli forces have killed scores of thousands of people in Gaza and thousands in Lebanon, the answer is not obvious. At no time in history have Americans, especially those on elite university campuses, been so exercised about a conflict in which American youth were not being sent to die. The last major wave of campus protests – against South Africa’s apartheid regime during the 1970s and ’80s – pales in comparison with the current moment.

The question I am asking – why Israel? – is valid and important, but only if approached with honesty and an open mind. All too often this question is employed by Israel’s supporters as a rhetorical tool known as tu quoque, or, in simple English, ‘what about?’ What about millions of deaths in Ethiopia, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one might ask. Or mass killing and destruction of cities in Syria? Or widespread Russian atrocities in Ukraine? What about mass incarcerations in China’s Xinjiang Province, and the ongoing Sinicisation of Tibet? Why didn’t students disrupt classes, occupy and vandalise buildings, and set up encampments when US forces killed hundreds of thousands of civilians during the Persian Gulf War?

These are fair questions but, when employed as a form of advocacy, ‘what about’ is in fact a hostile riposte, a means of suppressing criticism. When raised in connection with Israel, it commonly invokes antisemitism as the ultimate explanation for global ire against the Jewish state.

Antisemitism has always played a role in accounting for animus towards Israel. But it is not the only factor. Ever since Israel’s creation and the Palestinian Nakba in 1948, Palestine has served as an affective magnet that attracts and generates emotions such as religious fervour, anticolonial anger, and Holocaust guilt and shame. Other global conflicts evoke high levels of emotional intensity, but mainly within the region where they are waged and among the ethnonational communities that wage them. Russia is obsessed with Ukraine, the People’s Republic of China with Taiwan, and ethnic strife in sub-Saharan Africa has killed millions, but few Americans who are not of Russian, Chinese or African origin are as emotionally invested in these struggles as they are in Israel/Palestine.

The prominence of Israel/Palestine in public opinion cannot be explained only in terms of the number of deaths, nor in the extent of Gaza’s or Lebanon’s ruination, nor in the Palestinians’ status as a dispossessed and oppressed people. (There are others, such as Kurds, Masalit, Rohingya, Sahrawis, Uyghurs, and Yazidis.) All national conflicts generate waves of emotion, but Israel/Palestine generates tsunamis. Or, to switch metaphors, Israel/Palestine is a superconductor of emotional current. There’s nothing else like it.

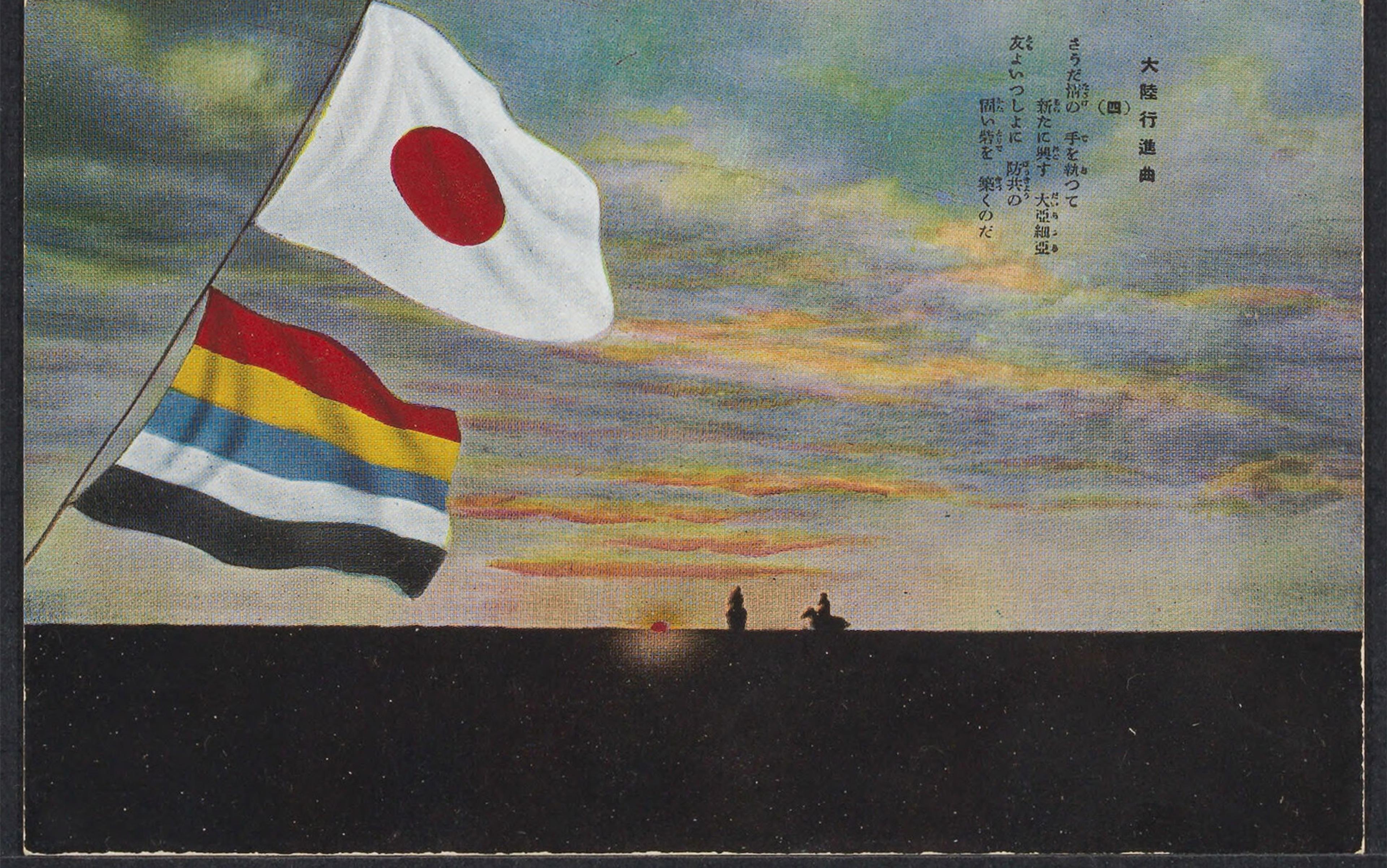

The source of Palestine’s uniqueness lies in the past. During the 1800s, the ancient religious significance of Palestine for Christians, Jews and Muslims became politicised. First, Palestine fell into Europe’s colonial orbit, and then it became both the object of the Zionist movement’s yearnings for a Jewish homeland and a site of early Arab nationalism. Palestine’s significance as a subject and object of political emotion expanded during the interwar period, when Britain held a League of Nations mandate to govern Palestine. Zionists found British rule to be at first exhilarating but then infuriating, as early expectations of Jewish sovereignty gave way to accusations of betrayal when Britain attempted to balance its commitments to Zionism with its geopolitical interests in the Arab world. The British Mandate, in turn, exasperated and enraged Arabs and Muslims, whose strivings for independence made progress throughout Asia but were blocked in Palestine. These politically framed emotions enhanced, and were in turn amplified by, religious sentiment. In 1929, rumours that Jews planned to purchase the Temple Mount (the Al-Aqsa mosque compound) in the Old City of Jerusalem provoked calls among Palestinians that ‘Al-Aqsa is in danger’ – a phrase that has remained in use to this day.

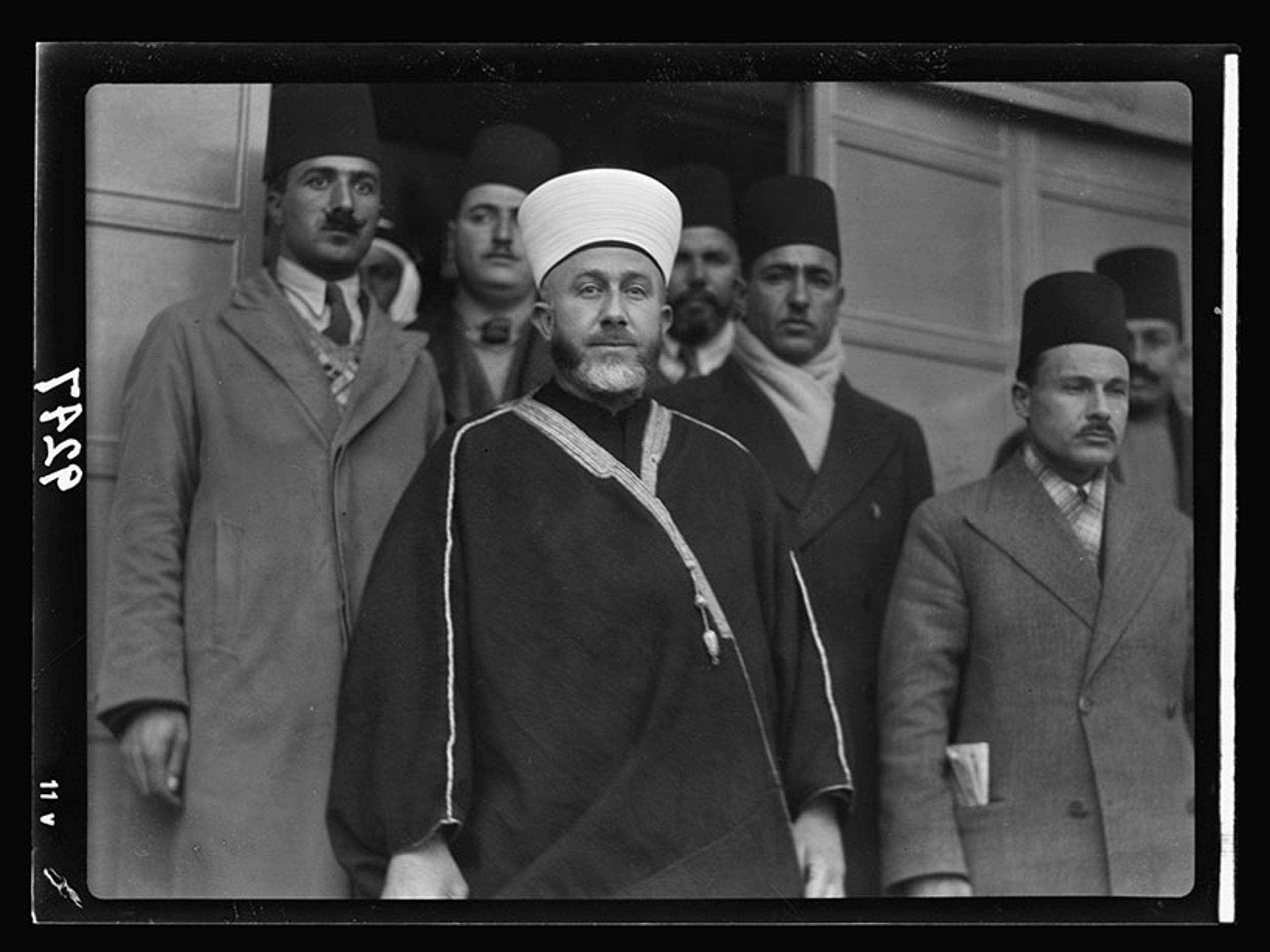

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, with attendants, leaving the offices of the Palestine Royal Commission in 1937. Courtesy Library of Congress

In 1931, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini – the mufti of Jerusalem – and the Indian Muslim leader Shawkat Ali convened a World Islamic Conference in Jerusalem that strengthened perceptions of Palestine as not only a pan-Arab concern but also a pan-Islamic one. After the Second World War, just as the world’s Jews, reeling from the genocide of European Jewry, united around the call for a Jewish state, Palestine grew into a symbol of anticolonial aspirations. In the Western world, which perpetrated the Holocaust, abetted it or stood by while it took place, the fate of the Jews was a sensitive and fraught subject. Despite professions of sympathy for the survivors, few countries in Europe or the Americas wanted to repatriate them or accept them en masse as refugees. For many countries, shunting the survivors to Palestine was an attractive solution – an option advocated by the vast majority of Jews and opposed just as strenuously by the Arabs of Palestine and throughout the Muslim and Arab worlds. During the immediate postwar years, the world was rife with crises – civil war in China and Greece, anticolonial uprisings in Indonesia and Indochina, and the division of Europe between East and West. Even then, what was widely known as the ‘Palestine Question’ had the greatest global reach.

Solidarity with a colonised people helped produce strong contemporary support for the Palestinian cause

In 1947 and ’48 – the years of the United Nations’ debates about partitioning Palestine, the 1948 war, Israel’s establishment, and the Palestinian Nakba – global discourse about Palestine expanded still further and grew even more intense than during the interwar era. The United States’ Middle East policies in 1948, and US responses to events in Palestine, have received a great deal of scholarly attention, but ‘the Palestine Question’ was even more prominent and controversial in Asia from the Arab Middle East to the Subcontinent, in western Europe, and in Latin America. It commanded global attention.

The Arab Muslim heartland was both an observer of and a participant in the struggle for Palestine. Many Arab Muslims responded to the international community’s endorsement of partition with incredulity, indignation and profound fear that a Jewish state would dominate the region. On the Subcontinent, solidarity with a colonised people (and, for India’s Muslims, co-religionists) helped produce strong contemporary support for the Palestinian cause. That support was also more measured and less inclined to draw upon antisemitic motifs than in the Middle East. In Europe, the Holocaust generated sympathy for Zionism rooted in compassion, shame and guilt, but antisemitism and Cold War political calculation caused considerable scepticism about the establishment of Israel. In Latin America, the presence of substantial Jewish and Arab communities, the legacy of the continent’s own anticolonial struggles against Spain and Portugal, and the influence of Roman Catholicism all fostered competing and contradictory sympathies for the antagonists in Palestine. The affective responses on these three continents were evident in force from the beginning of the UN debates about partition and formed a complex tapestry, much of which remains recognisable to this day.

When Britain handed the matter of Palestine to the UN in February 1947, the representatives of the states of the Arab League spoke of Palestine as an integral part of the Arab world. They demanded that it be established as an Arab state. These Arab leaders were incredulous and indignant that the UN, an organisation dominated by the colonial powers, would assume the authority to intervene in Palestine’s natural path towards independence. The Arab Higher Committee (AHC), the umbrella group of Palestinian political parties, boycotted the UN’s enquiries.

Nonetheless, in July 1947, members of the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) met in Geneva with the Palestinian leader Musa Alami and in Beirut with political and diplomatic figures from Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. All of them demanded statehood for what they called the Arabs of Palestine, whom they also referred to as Palestinian Arabs or, more rarely, Palestinians. They justified the creation of a Palestinian state via appeals to universal human rights, the principle of popular sovereignty, and the Arabs’ historic presence in Palestine. In turn, they depicted Zionism as the handmaid of British and, more recently, US colonialism. (‘Colonialism’ as understood in this sense referred to Great Power desire for political and economic control over the Middle East. The displacement of Palestinians that lies at the heart of the currently popular notion of settler colonialism had barely begun.) Following a long line of anti-Zionists, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, the Arab diplomats also denied that Jews constituted a nation and so they had no right to self-determination. The Arab diplomats insisted that Jews were a religious community, whose freedom of religious practice would be guaranteed in a Palestinian Arab state.

Whether one agreed with these arguments or not, they had historical and ethical foundations. The resentment and anger underlying these claims, however, led to an embrace of overtly antisemitic views. Faris Bey el-Khouri, an eminent Syrian politician and diplomat, told the UN General Assembly that Jews had no claim on Palestine because 90 per cent of eastern European Jews were descended from Slavs, Germans, Franks and Khazars, without a connection to the ancient Middle East. (The ‘Khazar hypothesis’, attributing the origins of Ashkenazic Jewry to a dubious mass conversion of the medieval Khazar kingdom in the Caucasus, was commonly invoked in Arab critiques of Zionism at this time, and remains popular.) El-Khouri added that ‘the choice of Palestine to satisfy Zionist aspirations was based not on humanitarian sympathy but on the intention of the Zionists in the United States to launch an economic invasion of the whole eastern world and to achieve that end by creating a bridgehead in Palestine to be the headquarters of their activities.’ Such a state would rely on the US and on the Zionists’ ‘coreligionists’ in the US, who had thus far flooded Palestine’s Jewish community with dollars to give it what el-Khouri called the ‘symptoms’ of prosperity.

The Arab Higher Committee accused Zionist forces of having crucified Arab prisoners

In late 1947, when fighting between Jews and Arabs in Palestine broke out, Arab public rhetoric see-sawed between realistic and fantastic assessments of the Zionists’ war aims and methods. In January 1948, the Austrian ambassador in Ankara spoke of moderate Arabs who were willing to accept partition but feared – accurately, as it turned out – that Jews would infiltrate territory allocated by the UN to the Arab state. In May, however, the Jordanian ambassador to Ankara said that Palestine’s Jews planned to invade the entire Levant and that Arab Legion troops had found maps of Palestine and Iraq proving Zionist intentions to establish a Jewish empire.

In 1948, the AHC submitted pamphlets about the partition to the UN that toggled between accuracy and baleful myth. The pamphlets accused Zionists of barbaric and intentional cruelty towards the Arabs of Palestine. Zionist actions, such as the notorious massacre in April 1948 of some 100 Arab civilians in the village of Deir Yassin, on the western outskirts of Jerusalem, provided some justification for such an accusation. The Egyptian embassy in Vienna, for example, responded to the massacre by contending that the ‘true purpose of Zionism is the complete annihilation of the Arab element in these territories.’ The AHC pamphlets, however, went even further, claiming that Jews were eternally and preternaturally violent. Their ‘cold-blooded and well-calculated Zionist plan for the massacre of populations’ was ‘a renewal of the technique adopted by them when they first entered Palestine about the year 1400 BC.’ Zionist savagery, according to the AHC, reflected their longstanding status as ‘international intriguers’, controllers of ‘the channels of propaganda in important countries’. Jewish global power, embodied in the Jewish Agency, had enabled the construction of a ‘totalitarian’, ‘fanatic’ and ‘terrorist’ community in Palestine, employing means of violence ‘equalled only by the Nazis’. The AHC accused Zionist forces of having crucified Arab prisoners.

The Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question of the United Nations General Assembly in Lake Success, New York, November 1947. Courtesy UN Photo

This language reflects not only hatred but also deep-seated fear – fear stoked by the UN’s approval of the partition of Palestine in November 1947. On the day after the passing of the partition resolution, the Syrian education minister, Munir al-Ajlani, spoke of the ‘liberation of Palestine and the conservation of Arabism in spite of the great world conspiracy against us.’ Al-Ajlani feared an impending ‘catastrophe’ (nakba) for Syria and the entire Arab world. Shortly thereafter, Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, described Palestine as the Muslim world’s ‘first line of defence’ of Islam, and in 1949 he described Israel’s creation as the product of a Jewish conspiracy against the Arab world and Islam alike.

Al-Ajlani’s application of the term nakba to the Arab world, rather than the Palestinians in particular, is telling. During and immediately after the Second World War, what became known in later decades as the onset of the Palestinian Nakba – the dispossession of their homes and homeland – had a more popular meaning. In his booklet The Meaning of Catastrophe (1948), the Syrian intellectual Constantin Zureik used the term nakba to depict the disunity, backwardness and weakness of the Arab world, as opposed to the alleged towering strength and fortitude of its Zionist enemy. A zealous proponent of political pan-Arabism, Zureik saw Israel as the greatest threat to the creation of a powerful, vibrant and healthy united Arab polity. He fretted that, if under the current circumstances such a state were created:

the Zionist danger will gradually permeate our sickly, worn body with a cancerous taint, and one day we will wake up and lo! All of Palestine will be in the hands of the energetic, militant Zionist minority …

Even more worrying, Zureik said in a radio broadcast on 31 May 1948:

The facility that the Zionist forces have for growth and expansion will place the Arab world forever at their mercy and will paralyse its vitality and deter its progress and evolution in the ladders of advancement and civilisation – that is, if this Arab world is permitted to exist at all … We struggle simply to defend ourselves against a treacherous aggression and to protect our very existence.

In Arab responses to the war, the line between manipulation and sincere belief was blurry. Shortly after the Deir Yassin massacre, Hussein Fakhri al-Khalidi, secretary of the AHC, directed the Arabic service of the Palestine Broadcasting Corporation to depict the atrocities in the most gruesome terms, including graphic allegations of rape. Al-Khalidi hoped that lurid narratives about Jewish atrocities would bolster the Palestinians’ determination to fight against the Zionist enemy and dissuade them from fleeing the country. (The opposite was the case: both Arab and Zionist propaganda intensified Palestinian fears for their lives and accelerated Palestinian flight.) Even if Arabs at times intentionally exaggerated the Jews’ malevolence, the malevolence was taken for granted. In 1947 and ’48, Arab fear and hatred of Zionists in Palestine was entangled with fear and hatred of Jews everywhere and throughout history.

In South Asia, Muslims had a different approach. They had a long history of sympathy for the Palestinian Arab cause, but in 1947 and ’48, the partition of India and its aftermath overwhelmed their concerns for Palestine. (Between August 1947 and January 1948, at least 10 million Hindus and Muslims fled for India and Pakistan respectively, and a million died in intercommunal violence.) Perhaps for these reasons, or maybe because of physical and cultural distance from the Arab Muslim heartland, the rhetoric of Indian Muslims was relatively free from antisemitism. Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, who after partition became Pakistan’s first foreign minister, was a fierce critic of Zionism, as was the Muslim League, the political party that, since the early 20th century, had championed the interests of India’s Muslims. In his memoirs, however, Khan chided his Arab counterparts in the UN for resorting to antisemitism, which he saw as unnecessary to their cause. Khan thought that Arab Muslims weakened ‘solid arguments’ with speech that was largely ‘emotional’:

and the speakers spent most of their time in a vain effort to prove that the Jews coming to settle in Palestine were not the descendants of Abraham, and belonged to a Russian tribe named Khazar whose forefathers in a distant past had converted to Judaism. The Arab cause in all its aspects was so strong and just that to support it with such irrelevant arguments amounted to weakening it.

In 1940, Khan proposed a federal scheme for Palestine with neither partition nor population transfer, claiming that

the forcible creation of a Jewish state within the heart of the Arab world would constitute a serious factor of disturbance, not only within the boundaries of Palestine, but would also jeopardise the peace and international security throughout the Middle East.

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan in 1939. Courtesy the NPG London

In 1947, Khan repeated these arguments at the UN, while the Muslim League fiercely objected to any justification for the partition of Palestine via references to the ongoing partition of India. Indian Muslims who accepted the creation of Pakistan were parties to a partition with at least some measure of mutual agreement, whereas the partition of Palestine was being forced on Arab Muslims. Indian Muslim leaders pointed out that the partition of India was based on demographic majorities within provinces, whereas in Palestine Jews formed a majority only in the district of Tel Aviv and its environs.

The Indian press strongly supported an independent Arab Palestine

Mohammad Abdur Rahman, a distinguished jurist in Lahore and the Indian delegate to UNSCOP, opposed the partition of Palestine in principle, and as the result of personal experience. While he was working for the committee, his country was being torn apart by partition. Abdur Rahman’s family was forced to flee its home and their possessions in Delhi, barely making it to Lahore. Under pressure from the prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Abdur Rahman proposed to UNSCOP a Jewish-Arab federation that resembled Khan’s idea, but he preferred a unitary Palestinian state with guarantees of religious freedom for Jews. Dismayed by the partition vote, Abdur Rahman predicted that the partition of Palestine would turn out badly, writing that ‘there is no other land in the whole world which arouses so much religious sentiment and feeling.’ A year after the vote, Abdur Rahman wrote to another committee member, the Canadian jurist Ivan Rand, who had forcefully supported partition, ‘please do not call me presumptuous as I say so with all humility, but I still feel that federation was and probably would be the best solution of Palestine as it would have been of [my] country also.’

The predominantly Hindu Indian National Congress shared the Indian Muslim opposition to the partition of Palestine, and for similar reasons. In October 1947, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Nehru’s sister and the Indian ambassador to the UN, cabled her brother that ‘the Arab demand is based on the same principle of right of self-determination and freedom, which [the Indian National] Congress … has always fought for.’ During debates, the Indian press strongly supported an independent Arab Palestine. Referring to the British tradition of using religion as a divide-and-rule strategy in India as well as recent ‘tragic conditions’ in the country, The Leader, The Bombay Chronicle and the National Herald, all of which had ties to the Indian National Congress, urged that, when considering Palestine’s future, UNSCOP should not take religious differences into account. Throughout 1947 and the first half of 1948, The Times of India, whose views were also close to the government’s, condemned partition, championed the proposal for a Palestinian state that Nehru had devised, and characterised both Jews and Arabs as ‘inspired by and victims of narrow, essentially selfish and sectional interests.’ Yet in September 1948, the newspaper acknowledged that ‘actual and effective partition had been achieved by Jewish arms.’ For entirely different reasons, such pragmatism and non-partisanship was harder to come by in the Arab world, or, for that matter, in Europe.

Europeans who had committed, abetted or benefitted from the Nazi genocide of the Jews had a vested interest in endorsing Zionism as a means of expiating guilt. Or, to the extent that they were still antisemites, Europeans saw Zionism as a means of getting the surviving Jews out of Europe. Social-democratic and Soviet bloc governments with longstanding ties to the Zionist labour movement, which was the dominant political force in Palestine’s Jewish community, saw in a socialist Jewish state a kindred spirit and a blow to British imperialism in the Middle East.

In France, although the foreign and intelligence services cautioned against support for Zionism lest it harm relations with the Arab world, the government and public opinion favoured Israel’s creation. (The only exception was the Catholic Church, which at that time was not politically influential.) An intricate combination of sympathy for Jewish victims of the Holocaust, solidarity with Jews who had played a prominent role in the French resistance, and unacknowledged guilt for wartime indifference towards Jews (or outright collaboration with the Germans) led to frequent comparisons between the Jewish fighters in Palestine and the partisans in the French countryside, the maquis. When, in late 1947, three Jewish men were tried for arms smuggling on behalf of the Zionist paramilitary organisation the Irgun, the coverage in the Leftist and Gaullist press was sympathetic to the defendants. So was the judge, who said as much when he acquitted one of the men and handed out light sentences to the other two. The prestigious newspaper Le Monde wrote of Israeli smuggling of aircraft to Palestine with thinly concealed excitement and admiration of a ‘brilliant and massive improvisation’.

Joseph Kessel was France’s most prominent journalist of the time, a Jew of Russo-Lithuanian origin who attained literary fame as a novelist (he was the author of Belle de Jour), and in 1962 was elected to the Académie française. In his wartime dispatches from Palestine, which were published in major French newspapers, Kessel extolled the Zionists in language that reflected common Jewish sensibilities of the time: eg, intense admiration for the Israelis’ tanned bodies, calm demeanour, dedication and sensitivity. He also connected with his French audience via specific references to ‘the traditions of the maquis, the partisan fighters, and colonial engagements’. The Jewish state, he wrote, was ‘a vast maquis’, and its actions in war were ‘maquisard expeditions’. Like the maquisards, they had no uniforms, possessed only light arms, and kept their names and faces secret. Kessel described the ‘extraordinary Jewish people’ he encountered as constituting ‘a sort of Foreign Legion that had gathered on the soil of its ancestors.’ Kessel made frequent and hostile references to Britain, with whom the French had a long history of rivalry despite their wartime alliance, as the Jews’ true enemy.

The reportage had a Christian perspective, concerned with whether Jews and Arabs alike were threats to holy sites

Kessel wrote as a Zionist Jew, but his work was published in France’s major newspapers and aimed at a mostly non-Jewish readership. His writing was not an apologetics for Zionism in the face of Gentile criticism so much as a triumphant account of the establishment in Palestine of a maquis-state, composed of Jews from the Middle East as well as Europe, both dark- and pale-complexioned, and endowed with a mission civilisatrice towards what he depicted as the backward Arabs of Palestine.

French philo-Zionism had many sources, ranging from guilt to compassion, and saw no contradiction in conceiving of Zionism as both settler-colonial, on the one hand, and rooted in collective resistance and liberation, on the other. Ambivalence towards Zionism alongside unconcealed antisemitism nonetheless survived in Europe, including in the country that perpetrated the Holocaust, Germany. Until 1949, Germany was under Allied occupation and had no independent government, so it is difficult to access the real-time views of senior diplomats and political leaders on the Palestine Question. But despite Allied control and censorship, there was a relatively free press, whose representations of Palestine are surprising. Between the partition vote at the end of November 1947 and the first truce in mid-June the following year, Palestine was on the front page of the major German newspapers on a regular basis – and, for some periods, for weeks at a time. In 1948, the popular newsmagazine Der Spiegel covered Israel in 29 issues, as opposed to 20 for China, 12 for Greece, seven for India, and five for Indonesia. Most of the newspapers’ stories came from wire services and contained no analysis or commentary, but their prominence is revealing. During these immediate postwar years, German newspapers were slender, at most eight pages, and they carried a page or two of foreign news. News from trouble spots like Palestine, China or India competed for precious space with the brewing Cold War in Europe, the Marshall Plan, the currency reform in the western zones of occupied Germany, and, from June 1948, the Berlin blockade. Nonetheless, the war in Palestine, even if reported in the most neutral manner, was of paramount concern. Much of the reportage concerned Jerusalem and reflected a Christian perspective, concerned with whether Jews and Arabs alike were threats to holy sites. The little commentary tended to bemoan the war in general terms and expressed little sympathy for the Zionist cause.

The weekly newspaper Die Zeit, based in Hamburg, took a more hostile position towards Israel. The future doyenne of German journalism, Marion Dönhoff, began her career as the newspaper’s Middle East expert. Hailing from an old Prussian aristocratic family, she opposed the Nazis but was no republican and not free from antisemitism. For Dönhoff, Israel was a ‘foreign body’ that stood in the way of a territorial contiguous Arab realm with capacity for ‘an independent creative Arab politics’ nourished by Saudi oil revenues. Israel, Dönhoff, wrote, could not possibly solve the ‘Jewish problem’ as it was too small, and Arabs would never accept it unless it prohibited additional Jewish migration. Dönhoff described Israel simultaneously as a staging ground for Soviet communism and a continuation of Nazism in the form of a ‘noxious’, ‘extreme’ and chauvinistic nationalism.

On the other hand, the German weekly Der Spiegel covered the Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion as a hero. Der Spiegel also condemned Amin al-Husseini as a Nazi ideologue and collaborator, and it criticised the US and the UN for retreating from support for partition in the late winter of 1948. Der Spiegel featured several cover-page photographs of Israeli fighters, and it sympathetically documented the travails of displaced persons striving to get to Israel. Antisemitism, however, showed up in the magazine as well. In a story about female passengers on the SS Exodus who had, after a gruelling and protracted ordeal, finally arrived in the Jewish state, the magazine wrote that ‘many of the …women today wear gold rings, are manicured, made-up, and banknotes pile up in their husband’s briefcases.’ Der Spiegel described Tel Aviv as containing the ‘concentrated financial power of world Jewry’. Despite their interest in the travails of displaced Jews from Europe, Der Spiegel never mentioned why they were displaced. The magazine made no connection between the Nazi genocide and the displaced persons, it juxtaposed Christianity as a religion of peace versus the allegedly fanatical, hateful and enraged behaviour of Jews such as the refugees on the SS Exodus. Like Die Zeit, Der Spiegel took pains to condemn the Irgun and Stern Gang as ‘Jewish fascists of the first order’.

In 1948, during the war over partition, Germany had neither a government nor a foreign policy, but Austria did. Diplomatic correspondence from Austria’s ambassadors in the Middle East to its foreign ministry in Vienna show antisemitism shaping Austrian views. Israel, wrote the Austrian ambassador in Ankara in 1948, is divided between moderates and communists, or to be more specific, ‘western, democratically oriented Jews’ and ‘outcast eastern Jews who know no limits’. Notions of Jewish financial and political power in the US were omnipresent in the correspondence. So was the belief that Jews in Palestine enjoyed considerable wealth, some of it earned by German immigrants who moved to Palestine in the 1930s and manufactured knockoffs of patented German goods. Again, as in the German newspapers, the circumstances behind these Jews’ sudden departure from Europe passed unmentioned. In December 1948, a letter from the Austrian ambassador to the Holy See referred to ‘atrocities during and after the Second World War’. It did not mention the atrocities’ nature, scope, victims or perpetrators.

In Latin America, sympathy for Jewish victims of the Holocaust was largely free from the guilt felt by its European perpetrators and bystanders. Physical distance from both the killing fields of Europe and the battlefields of Palestine made for a more abstract approach to the Palestine Question. Enrique Fabregat of Uruguay and Jorge García-Granados of Guatemala, for example, were liberal, pro-Zionist members of UNSCOP. Fabregat was a Christian humanitarian and hostile to fascism; both of these commitments originated in the struggle against Francoist Spain. García-Granados shared these political views as well as anti-imperial animosity towards Britain, the master of neighbouring British Honduras (later, Belize). Zionist lobbying groups promoted Fabregat’s and García-Granados’s affective blend of attachment, admiration and solidarity against a common enemy throughout Latin America. The Jewish Agency, the Zionist proto-governmental body based in London and Jerusalem, established these groups following the Second World War in virtually every Latin American state. They were called ‘Pro-Palestine committees’, a reminder that before 1948 the word ‘Palestine’ was employed by both Zionists and Palestinian Arabs to refer to the same territory.

Across Latin America, the Pro-Palestine Committees, which had hundreds of members in larger Latin American states and dozens in smaller ones, mobilised the elite of their countries’ societies – politicians, judges, professors, attorneys – to lobby state governments to support the Zionist cause. There were similar organisations in the US, but in Latin America there was one major difference – the presence of significant communities of Arab immigrants, often Christians from Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. The Arab Christians in Latin America were often behind the Palestinian cause. In Argentina, the Zionist Pro-Palestine Committee’s nemeses included the Prensa, described as:

an appeal to human solidarity. 400,000 persons displaced from their land and their homes in Palestine wait for help. CONTRIBUTE WITH YOUR AID to mitigate the indigence of so many thousands of children, old people, women and men who suffer from hunger and untold misery.

In the US, this kind of philanthropic organising and emotional messaging was far more widespread among Jewish organisations than Arab ones. In Latin America, Jews and Arabs fought on a more level playing field.

Then, as now in the US, people projected domestic political scenarios onto Middle Eastern terrain

As a result of these duelling pressures from Arab and Jewish groups alike, a half dozen Latin American governments abstained in the UN General Assembly vote on 29 November 1947 on the partition of Palestine. In doing so, Argentina and Mexico and other Latin American countries signalled their independence from the US, which had urged them to support partition. But it is also important not to underestimate the domestic political forces at work. Uruguay and Guatemala expressed support for partition before the US did. The Chilean president, Gabriel Gonzáles Videla, was pro-Zionist and was involved in his country’s Pro-Palestine Committee. Nonetheless, lobbying from the Chilean Arab community led Videla’s government to abstain from supporting partition. In Argentina, president Juan Perón’s decision to abstain on the partition vote was an acknowledgment of Argentinian Arab support for his regime. Despite US pressure, Cuba voted against partition. Ernesto Dihigo, who gave an impassioned speech at the UN supporting the Palestinian Arab right to self-determination, cast Cuba’s negative vote. The decision to vote against the resolution, however, came directly from the Cuban president, Ramón Grau San Martín, due to lobbying by Cuban Arabs and pique at the US over sugar trade policy.

The competition between Jewish and Arab communities in mid 20th-century Latin America reminds us of our own day, where Muslim and Arab voices in the US are growing more prominent. Then, as now in the US, people projected domestic political scenarios onto Middle Eastern terrain. As Mexico’s foreign minister in the late 1940s, Jaime Torres Bodet, wrote in his memoirs:

Personal sympathy made me prone to understanding the Jewish cause. But the historical rationale, and the memory of the case of Texas, forced me to imagine – as a Mexican – the reaction that the Arab people would necessarily have.

In November 1947, Mexico’s newspaper of record, Excélsior, also related the Palestinian cause to Mexico’s loss of territory to the US a century earlier:

The colonisation of a territory belonging to an economically weak and, naturally, less organised people, by organised groups with much greater economic power … would give birth to another injustice instead of solving the one committed against the Jews … Whosoever has suffered in flesh and blood the experience of Texas and everything else that occurred there has the authority to present themselves in every way as a defender of the right of the people to govern themselves.

Mexico itself was a settler-colonial state that had gained independence from Spain less than three decades before its defeat by the US. In 1948, as today, the interpretation of events in Palestine through the subject position of the observer was common.

The partition of Palestine and the 1948 war riveted the world. The emotional matrix framing Israel/Palestine at the time of the 1948 war – anticolonial anger and frustration, as well as a mixture of shame, guilt and compassion in response to the Holocaust – has proven highly durable. The antisemitism exemplified by German and Austrian coldness to Israel, and German, Austrian and Arab fantasies of Jewish aspirations for regional domination have also endured. The blend of sympathy for the Palestinians and antisemitism was not limited to the Arab world. On the day that the Mexican newspaper Excélsior published its editorial comparing Palestine with Mexico, it published another editorial accusing Jews of having ‘been repeatedly converted from persecuted to persecutors and vice-versa throughout their entire history.’ Moreover, ‘wherever they are, [Jews] isolate themselves, without mixing themselves or even less merging themselves with who they live with.’ Due to their ‘cohesion and solidarity … they are able to rapidly triumph in all means, finally becoming hated and provoking the most extraordinary explosions of violence against them.’ In other words, according to the editorial, Jews deserve to be hated and have invited their own persecution – perhaps not for killing Christ, but for their invariable success.

On the eve of Israel’s creation and the Nakba, people throughout the world viewed Palestine with powerful and varied feelings. Then, as now, Christian and Muslim fervour, anti- and philo-semitism, anticolonialism, altruistic humanitarianism and political self-interest all shaped how people around the world saw the region. The extraordinary symbolic power of the Holy Land to Muslims and Christians everywhere; a fascination, even obsession, with Jews that has both positive and negative valences; and anti-imperial principle and anger at the US for reasons beyond its support of Israel have all fuelled acute and enduring passions about Israel/Palestine. Palestine has become a palimpsest onto which people around the world project problems within their own countries, adding another layer of commitment – and, often, distortion. The magnitude and intensity of feelings about Palestine in the immediate postwar period, feelings created by an interaction of multiple, overlapping historical forces of singular strength and intensity, created an affective black hole possessed of enormous power, which remains with us to this day.