On 22 December 2012, the distinguished African-American film director Spike Lee tweeted: ‘American Slavery Was Not A Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western. It Was A Holocaust.’ He ignited a small storm in the US media, saying that he would not see Quentin Tarantino’s new film Django Unchained because it was an insult to his ancestors. Less than a month later, at the Berlin premiere of the movie, Tarantino himself declared that American slavery was a Holocaust. The German media chided him for his ‘provocative’ and ‘exaggerated’ remarks, but concluded that it was the sort of thing audiences in Germany — where he is extremely popular — have come to expect from Tarantino.

If someone had predicted a year ago that I would find myself writing about a Tarantino film, I would have bet a large sum against it. I didn’t even want to see one. Because it was the subject of intense discussion over issues I care about, I had dragged myself to see his previous film, Inglourious Basterds (2009), and found it bearable, but I had no interest in his other work. Tarantino seemed to suggest that you can revel in every form of violence and exploitation so long as they are depicted with skill and plenty of irony; you can take gun-dealing — arguably the lowest form of human occupation — and make it seem hip and sexy. Aren’t moral objections to this sort of thing simply uncool?

But my view of Tarantino changed profoundly as I watched Django Unchained the night it opened at my local cinema in Berlin. For the film is spiked with complex references that made clear how profoundly Tarantino had been influenced by German attempts to come to terms with the shame of its criminal past. Since those attempts are not well-known to a wider American or British public, it is important to sketch them — not only to understand Tarantino’s latest work, which is barely intelligible without that background, but to address the broader questions of what other nations can learn from Germany’s struggles to address its own historical guilt.

Germans have been wrestling with the question of history and guilt for more than 60 years now. Their example makes clear just how many moral questions a serious contemplation of guilt must raise for America. These include what constitutes guilt, what constitutes responsibility, and how these are connected. A common slogan of second-generation Germans has been: ‘Collective guilt, no! Collective responsibility, yes!’ But the question of what responsibility entails has been politically fraught. Does taking responsibility for a violent history demand an eternal commitment to pacifism? Or to supporting the government of Israel whatever it does, as some argue? Or rather to supporting the Palestinian people whatever they do, as others have claimed?

Working through Germany’s criminal past involved confronting one’s own parents and teachers and calling their authority rotten

Contemporary Germans understand collective responsibility as meaning a commitment to avoiding in the future the sins their fathers and grandfathers committed in the past — but this raises fresh moral tangles. Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels and a few others offer clear cases of guilt and responsibility: they planned and carried out crimes with malice and forethought. What about those who didn’t plan them, but merely carried them out without much thought of any kind? Were those who signed orders on desktops more guilty (because further up in the hierarchy) than the guards who herded naked Jews to their deaths? Or is a human being who is capable of doing that to another human being more depraved than a bureaucrat such as Eichmann, who claimed that watching a mass execution made him sick? And what about the voters who put the Nazis in power, hoping it would stop the inflation, streetfighting, and general chaos that threatened to engulf the Weimar Republic?

Of course, there are those who say they worked with the Nazis in order to prevent worse things that might have happened had less scrupulous people done their jobs. There were many of these, ranging from the Jewish councils who helped prepare the lists for deportation to the State secretary of the Foreign Office, Ernst von Weizsäcker, who was instrumental in a host of crimes, but successfully argued at his trial that anyone else would have done worse.

These are just a few of the moral questions that cannot be avoided when you begin to examine real, historical cases of evil. Hannah Arendt tried to tackle them, with the result that her book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) was surely the most vilified work of 20th century moral philosophy. Her careful attempt to understand forms of responsibility and to disentangle responsibility from intention was misunderstood by nearly everyone, and created furore and fury even among those who had been her close friends. Perhaps it’s not surprising that so many moral philosophers since have preferred to stick to trolley problems.

The German language has a word for coming to terms with past atrocities. Vergangenheitsbewältigung came into use in the 1960s to mean ‘we have to do something about our Nazi past’. Germany has spent much of the past 50 years in the excruciating process of dealing with the country’s national crimes. What does it mean to come to terms with the fact that your father, even if not a passionate Nazi, did nothing whatever to stop them, watched silently as his Jewish doctor or neighbour was deported, and shed blood in the name of their army? With very few exceptions, this was the fate of most Germans born between 1930-1960, and it isn’t a fate to be envied.

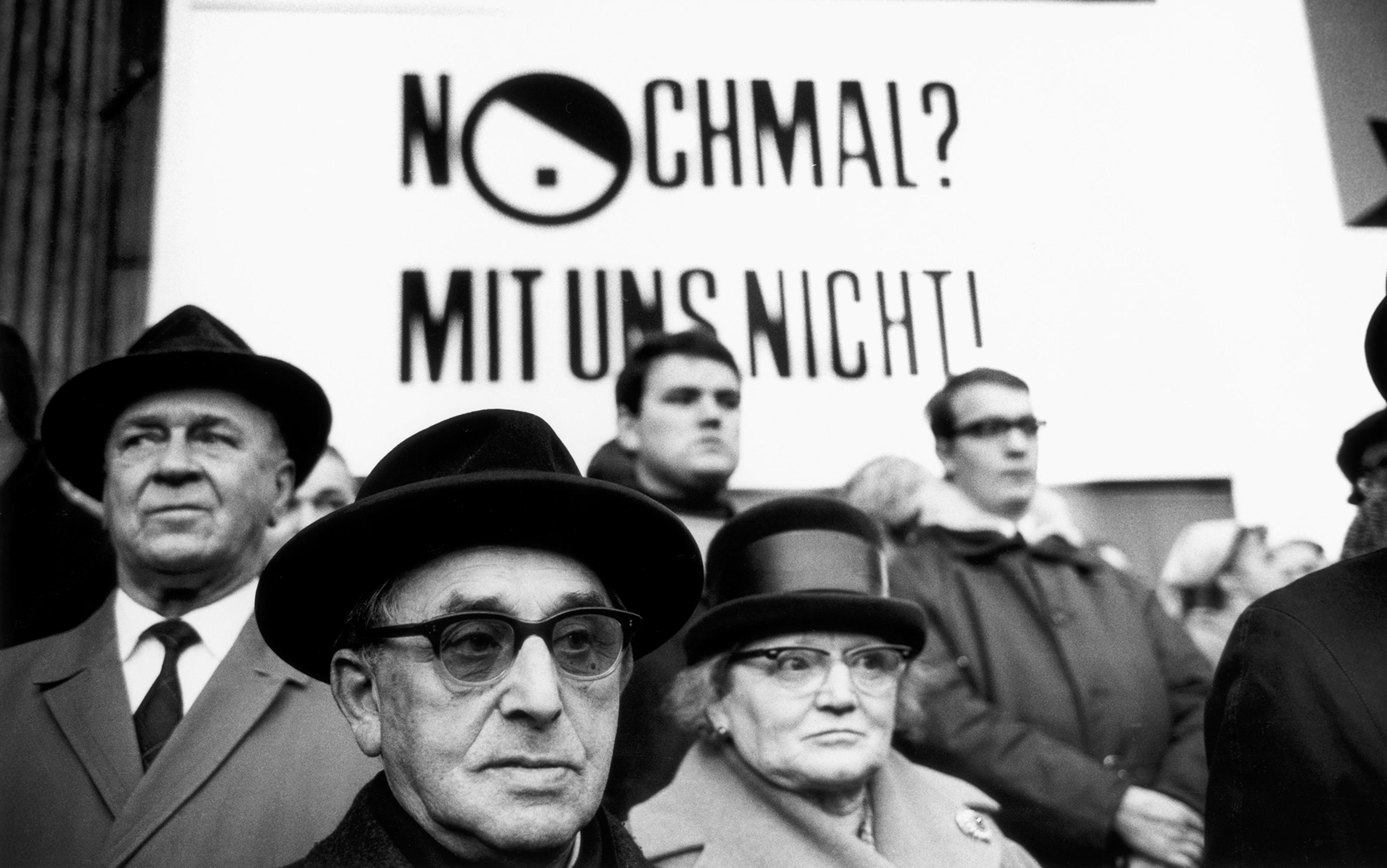

Working through Germany’s criminal past was not an abstract exercise; it involved confronting one’s own parents and teachers and calling their authority rotten. The 1960s in Germany were more turbulent than the 1960s in Paris or Prague — not to mention Berkeley — because they were focused not on crimes committed by someone in far-off Vietnam but considerably closer to home, by the people from whom one had learnt life’s earliest lessons.

The process of Vergangenheitsverarbeitung functioned quite differently in the Eastern and Western zones. Nazi propaganda had been far more interested in stirring fear of the ‘Bolshevist Jewish menace’ than of any other enemies, so when the Red Army advanced towards victory in Berlin in 1945, millions of Germans moved west to escape them. Those who had been committed Nazis, or simply knew something of the 20 million Soviet citizens that the German troops had killed, were understandably afraid of becoming targets of revenge. All of this meant that, when the guns stopped firing on 8 May 1945, more Nazi sympathisers lived in the West than in the East.

The country was divided into occupied zones, each ruled by a particular Allied military, while the Allies considered what to do with 74 million people who had committed, condoned, or ignored some of the worst crimes in human history. The Soviet and western Allies managed to co-operate long enough to carry out the Nuremberg Trials, which convicted a few of the most prominent war criminals. Both also instituted plans for re-education, which came to be known as ‘denazification’. Generally, the Soviets looked to German high culture as a source of inspiration, promoting theatre productions of the 18th-century philosemitic play Nathan der Weise (‘Nathan the Wise’) by the Enlightenment dramatist Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, while Americans leant towards lectures about freedom and democracy.

The generation that had fought the war refused to talk about the past

While neither effort was particularly effective, the process of denazification was promoted in the East thanks to the fact that hundreds of German communists were ready to return from exile to form the country’s leadership. The new German Democratic Republic of East Germany, created from the Soviet-governed zone in 1949, considered itself anti-Nazi. It expressed this by symbolically renaming streets, reshaping the city’s architecture along with its lesson plans, and commissioning a new national anthem, Auferstanden aus Ruinen (‘Risen from the Ruins’).

Without a leadership that was committed to confronting the nation’s crimes, the population of the Federal Republic of West Germany was even less willing to take up the mantle. With its cities still in ruins, its citizens — still reeling from the loss of sons and husbands on the front — were inclined to think of themselves as the war’s biggest victims. Not enough that the devastation of the war was evident on every street corner; on top of that, the occupying armies insisted that it was the Germans’ own fault! A few young intellectuals and artists agreed with the Allied perspective, and produced important works such as the film The Murderers Are Among Us (1946) and books by authors from the literary association Gruppe 47, whose members included the later Nobel laureates Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass. But neither the majority of German citizens nor their American overseers desired critical engagement with the Nazi period, nor sought to address the fact that the schools, courtrooms and police stations of the Western zone were still largely staffed by former Nazis. For the Cold War began before the Second World War ended, and the US president Harry S Truman’s administration was far more interested in undermining the Soviet Union than in rooting out former Nazis.

The 1950s and early ’60s offered little change. With all energies focused on rebuilding the economy, and most traditional authoritarian structures left intact, the generation that had fought the war refused to talk about the past. Accounts differ about when the silence began to break. Was it the series of radio programmes on anti-Semitism produced by the philosopher Margherita von Brentano? Or Rolf Hochhuth’s 1963 play Der Stellvertreter (‘The Deputy’) about the Pope’s complicity in the Holocaust? Or was it the Eichmann trial of 1961 together with the Auschwitz trial of 1963, which drew public attention and left major writing in their wakes? What’s undisputed is that, by 1968, young Germans including the future foreign minister Joschka Fischer were throwing rocks at police whom they considered to be not only the agents of present evils, but standing in a direct line with those responsible for evils past.

By 1968, few of those most directly responsible for Nazi crimes were running the show. But anyone who was staffing positions in the army, the police force, the intelligence service and the foreign ministry, among others, had been, at the very least, trained by former Nazi officials. It’s still sometimes thought that the Nazis appealed to illiterate mobs, a view unfortunately suggested by Bernhard Schlink’s dreadful book Der Vorleser (1995) and the subsequent movie The Reader (2008). In fact, the highest proportion of Nazi party members came from the educated classes. Without the sort of denazification that neither the Federal Republic nor its occupier were willing to undertake during the Cold War, there was no one initially available to staff leading institutions but old Nazis.

An old joke illustrates the problem. A former émigré arrives at Frankfurt airport and asks the first stranger he meets if he had been a Nazi. ‘Not me,’ says the stranger. The émigré asks the next man. ‘Heaven forbid!’ he replies. ‘I was always inwardly opposed to them.’ Finally, the émigré meets a man who admits to having been a Nazi. ‘Thank heavens!’ says the émigré. ‘An honest man. Would you mind watching my bags while I go to the toilet?’ For the next generation it was clear that Germany’s institutions needed to be overhauled from top to bottom.

The American television miniseries Holocaust (1978), though schlocky and little-noticed in the US, caused waves in Germany by exploring the ordinary human lives that lay behind the cold number of 6 million. The 50th anniversary of Hitler’s takeover was marked in 1983 in Berlin by a year’s worth of exhibits on topics as various as ‘Women in the Third Reich’, ‘Gays and Fascism’ and ‘The Architecture of Destroyed Synagogues’. Neighbourhoods vied with each other to explore their own local history. In Berlin, a play entitled It Wasn’t Me, Hitler Did It opened in 1977 and ran for 35 years.

When in 1986, the right-leaning historian Ernst Nolte suggested that Hitler had learnt most of his lessons from Stalin, he was accused by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas of trying to excuse German crimes. The ensuing ‘Historians’ Debate’ raged for three years — not in academic journals but in newspaper, television and radio discussions.

The prominence of the Holocaust in American culture serves a crucial function: we know what evil is, and we know the Germans did it

The mid-1990s brought a fresh shock when a Hamburg research institute decided to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the war’s end with an exhibit proving that not only the SS but many ordinary Wehrmacht soldiers participated in the perpetration of war crimes. To the rest of the world this was hardly news, but the exhibit prompted unexpected protest, and was even firebombed by those who claimed it dishonoured the memory of their fallen comrades or fathers; eventually a special session of parliament was convened to discuss it.

Nor has the need to rake through the Nazi period shown many signs of diminishing as the years go by. Just this spring, German viewers were offered an excellent television miniseries Unsere Mütter, unsere Väter (‘Our Mothers, Our Fathers’), depicting the ways in which four well-intentioned young people became slowly implicated in Nazi crimes.

In 1999 the German parliament voted, after years of public debate, to build the official Holocaust memorial in the most prominent piece of empty space in Berlin. I prefer a more unsettling monument to the past — the thousands of Stolperstein or ‘Stumbling Stones’ that the German artist Gunter Demnig has hammered into sidewalks in front of buildings where Jews lived before the war, listing their names, and birth and deportation dates. As some opponents predicted, the uses to which the Holocaust Monument has been put are anything but appropriate. But given that the centre of Berlin has been rebuilt with bombast, a bombastic Holocaust memorial, sticking out like a stylised sore thumb amid the triumphalist architecture of the Brandenburg Gate and its surrounding embassies and institutions seems just about right.

By comparison: can you imagine a monument to the genocide of Native Americans or the Middle Passage at the heart of the Washington Mall? Suppose you could walk down the street and step on a reminder that this building was constructed with slave labour, or that the site was the home of a Native American tribe before it was ethnically cleansed? What we have, instead, are national museums of Native American and African American culture, the latter scheduled to open in 2015. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian boasts exhibits showing superbly crafted Pueblo dolls, the influence of the horse in Native American culture, and Native American athletes who made it to the Olympics. The website of the Smithsonian’s anticipated National Museum of African American History and Culture does show a shackle that was presumably used on a slave ship, but it is far more interested in collecting hats worn by Pullman porters or pews from the African Methodist Episcopal church. A fashion collection is in the making, as well as a collection of artefacts belonging to the African American abolitionist Harriet Tubman; 39 objects, including her lace shawl and her prayer book, are already available.

Don’t get me wrong: it is deeply important to learn about, and validate, cultures that have been persecuted and oppressed. Without such learning, we are in danger of viewing members of such cultures as permanent victims — objects instead of subjects of history. The Jewish Museum Berlin is explicit about not reducing German Jewish history to the Holocaust. One section of the museum is devoted to it, but the rest of the permanent collection features things such as a portrait of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, filmed interviews with Hannah Arendt, a Jewish Christmas tree, and a giant moveable head of garlic. (Don’t ask.) The exhibit is awful, but presumably useful for those visitors whose only association with the word ‘Jew’ is a mass of gaunt prisoners in striped uniforms. In the same way, some Americans, no doubt, still need to see more than savage Hollywood Indians or caricatured Stepin Fetchit black people in order to get a more accurate picture of the cultures many of our ancestors tried to destroy. But more importantly, America’s museums of Native American and African American history embody a quintessentially American quality: we have always been inclined to look to the future instead of the past, and our museums follow suit. It’s impossible to compare what’s on display in our national showcase with what you can find in Germany without feeling that America’s national history retains its whitewash — and that a sane and sound future requires a more direct confrontation with our past.

We do have one place on the National Mall that focuses on unremitting negativity: the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. I am not the first person to ask why an event that took place in Europe should assume such a prominent place in our national symbolism — particularly when our government did little to save Jews before and during the Holocaust, yet ensured that former Nazi scientists could be smuggled into the US afterwards. The idea that it is evil to round up people and send them to gas chambers is about as close to a universal moral consensus as we get. And having a symbol of absolute evil unconsciously gives us a sort of gold standard against which most other evil actions measure only as common coin. Nazis function conveniently as place-holders of a paradigm of evil, useful to discredit opponents as varied as Saddam Hussein, Karl Rove, and Barack Obama. (It is truly terrifying to see how many pictures of Obama with a tiny moustache exist on the web.)

The prominence of the Holocaust in American culture serves a crucial function: we know what evil is, and we know the Germans did it. There is, of course, a large and growing body of work done by historians, cultural critics, and others that examines more specifically American forms of evil. Few of them, however, receive the same widespread public attention or sales figures as the latest book, film or memoir about yet another aspect of the Holocaust, which lets us have our cake and eat it, too. We can spend our time pondering serious matters, give appropriate expression to our horror, and lean back in the confidence that it all happened over there, in another country.

We no longer believe in bad seed or bad blood. Still, the idea that we are tainted by the sins of our fathers has a long and profound history. According to traditional Christianity, nothing we can do is enough to expiate them: we are all doomed to die for the fall of Adam and Eve, and salvation can come only after death. According to the Old Testament, we must serve some time for the sins of our fathers, unto the third and fourth generation. These traditions run deep even for those who might have rejected them, for they have a reasonable core. We all of us benefit from inheritances we did not choose and cannot change. Growing up involves deciding which part of the inheritance you want to claim as your own, and how much you have to pay for the rest of it. This is as true for nations as it is for individuals.

A Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung must force emotional confrontation with the crimes it concerns, not just a rational assessment of them. This confrontation was notably missing in the first decades of the Federal Republic of West Germany, which used reparations payments to the State of Israel as a substitute for facing up to what it meant to have caused the murder of millions. The country thus assumed forms of legal responsibility without really assuming moral responsibility until the slow, fitful turmoil of the 1960s. Mutatis mutandis, something similar has happened in America. Affirmative action measures are a way of taking collective responsibility for slavery and the blackface minstrel Jim Crow, but few white Americans have been forced to face just how awful slavery was. (And few of us know just how long it continued, in one form or another. I discovered by accident, when reading a biography of Albert Einstein, that he supported a group of clergymen who visited Truman’s White House in 1946 to push Truman to make lynching a federal offence. Truman refused.)

Some degree of traumatisation must take place. Facts are insufficient, and numbers often make them worse

This is why the violent scenes in Django Unchained were absolutely necessary. As both Tarantino and his black stars have said, real slavery was a thousand times worse than what they showed in the film. Tarantino edited out parts of the two most brutal scenes, in which men are torn apart by fellow slaves or packs of dogs, because early audiences found them too traumatic. Still, what he left in was brutal enough; as he said in an interview with the African American historian Henry Louis Gates Jr for The Root magazine: ‘People in general have so put slavery at an arm’s distance that just the information is enough for them — it’s just intellectual. They want to keep it intellectual. These are the facts, and that’s it. And I don’t even stare at the facts that much.’ To borrow a distinction from the philosopher Stanley Cavell: if we are to acknowledge, and not merely know, the extent of our nation’s crimes, some degree of traumatisation must take place. Facts are insufficient, and numbers often make them worse. As Gates notes, many of his students have become inured to the horror of slavery. Scenes such as Tarantino’s, which stay in our imaginations longer than any argument or historical description, offer a taste of immediacy with which we must linger before we go on.

To appreciate Tarantino’s intent, you have to take Inglourious Basterds seriously, which I initially did not. On first viewing, it’s easy to agree with The New Yorker’s description of the film as a baseball bat ‘applied to the head of anyone who has ever taken the Nazis, the war, or the Resistance seriously … too silly to be enjoyed, even as a joke’. However, one thing Tarantino does know well is the history of film. In one interview, he spoke of being influenced by Hollywood films of the 1940s, ‘when the Nazis weren’t a theoretical, evil boogieman from the past but were actually a threat’.

Film directors of that period — often European refugees such as Fritz Lang or Billy Wilder, as Tarantino pointed out — had no compunction about making war movies that were also exciting, entertaining, and even funny. Tarantino did the same. And if his fantasy that film could rewrite history might seem a tad extravagant (‘narcissistic’ is a cruder word for it), it’s a fantasy to which many Germans thrilled. A friend who has written a series of deep, complex and nuanced books on the subject of his nation’s criminal past told me he cheered like a child when Tarantino’s Nazis burst into flames. For all his erudition, the film had tapped into buried emotions that had moved and motivated him for decades. In a recent interview for Die Zeit, Tarantino said he was always being asked what Germans thought of Inglourious Basterds. ‘If anyone in the world dreams of killing Adolf Hitler,’ he answered, ‘aside from the Jews, it’s the last three generations of Germans.’ American history, German imagination: Tarantino got both of them right.

Tarantino is not the first American director to follow a major film about the Nazis with a film about American slavery. Steven Spielberg did the same when he followed Schindler’s List (1993) with Amistad (1997). Both are means for sending a message that Nazism should not be used to end discussions about evil but to begin them, and that American crimes deserve as hard a look as any other. In Django Unchained, Tarantino took it one step further than Spielberg in Amistad, by making the only decent white person in the film a German. The good guy could have been any old European, but Tarantino underlines his character’s German identity with constant references to it. And he rubs our noses in our own prejudices by using Christoph Waltz, the actor he cast to play the most memorable SS officer in film history, to be the only white person in Django who is viscerally revolted by American slavery.

The German presence in Django reveals the influence of German Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung on Tarantino’s films. While filming Inglourious Basterds, he lived in Berlin for half a year, which is long enough to get a sense of how Germans keep their awful past firmly in the present consciousness. His interview with Gates in The Root reveals just how conscious the influence was: ‘I think America is one of the only countries that has not been forced, sometimes by the rest of the world, to look their own past sins completely in the face. And it’s only by looking them in the face that you can possibly work past them.’ Nor does he shy away from the most direct comparisons. If there were a Nuremberg trial, he says in the same interview, then D W Griffith, the director of The Birth of a Nation (1915) — the silent film that inspired the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan — would be judged guilty of war crimes. And The Clansman (1905) — the book by Thomas Dixon on which that film was based — can for Tarantino ‘only stand next to Mein Kampf when it comes to its ugly imagery… it is evil. And I don’t use that word lightly.’

Some critics have questioned the appropriateness of a white director making a film about slavery, but that’s precisely the point of Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung. Tarantino has claimed that his great-grandfather was a Confederate general, which suggests that in making this film he was following in the footsteps of two generations of Germans and confronting ancestral evil.

The German reviews of Django whose headlines asked: ‘Dare we compare American slavery to the Holocaust?’ generally answered ‘No.’ In an inimitable blend of pedantry and cynicism, they explained the differences between slaveholding, which had an economic purpose, and the Holocaust, which had none. They then concluded that Tarantino had used the word provocatively to promote his film. As several commentators pointed out, the deliberately inflammatory use of the word ‘Holocaust’ is music to the ears of right-wing groups and should therefore be avoided at all costs. These reviews might show the wisdom of Tzvetan Todorov’s remark that Germans should talk about the particularity of the Holocaust, the Jews about its universality (applying Kant’s idea that if everybody worried about their own virtue and their neighbour’s happiness instead of the opposite, we would come close to a moral world).

But I am a little surprised that the American discussion of the film has focused more on counting the number of times the word ‘nigger’ is used than on the questions Django Unchained was meant to raise. Were Americans guilty of crimes that were as evil as those of the Nazis — and if so, what should we do about it today?

In a long attack on Django Unchained, the historian Adolph Reed argues that it represents ‘the generic story of individual triumph over adversity… neoliberalism’s version of an ideal of social justice’. While I applaud Reed’s attempt to call our attention to the pervasiveness of neoliberal ideology, I’m appalled by the idea that attending to individual stories is an invalid historical approach. The insistence that every human being has his or her own story is a statement about human freedom that is lost when we assume that ‘real’ history is only a matter of political economy and social relations.

After we’ve confronted the depths to which our history sank, we can — and we must — idealise those who moved it forwards. Tarantino’s heroes are as delightful as they are unbelievable; interestingly enough, his strength lies in depicting villains. Inglourious Basterds features two Nazis who are appealing, and very differently so. This is as it should be, if we are ever to understand how all kinds of ordinary, and even appealing, people commit murder, whether in Majdanek or in Mississippi. But it is equally crucial that we get our heroes right, too. Heroes close the gap between the ought and the is. They show us that it is not only possible to use our freedom to stand against injustice, but that some people have actually done so.

Yet, without some cultural experience of the violence that was a part of building this country, we risk the sort of liberal triumphalist narrative we would deplore if used elsewhere. There is much to be said for the American tendency to accentuate the positive. Rather than looking at the history of Jim Crow, we turn Martin Luther King’s birthday into a national holiday and put his statue on the Mall. Yet we would be disturbed by a German lesson plan that mentioned the Holocaust as a terrible thing, and then went on too quickly to described those heroes — Willy Brandt, Sophie Scholl, Claus von Stauffenberg — who opposed it. With far too few exceptions, America’s history of freedom-fighting — from Seneca Falls to Selma to Stonewall — is doing just that. It works for inaugural speeches, so long as you emphasise, as President Obama did, that we as a nation are on a journey in which there’s still a long way to go. Meanwhile, Tarantino’s approach is an antidote to triumphalism that’s all the more effective for being a roaring good film.