On 11 September 1939 in the city of Guadalajara in Spain, 13-year-old Ascensión Mendieta Ibarra opened the door to a group of ‘well-spoken’ men who had come to talk with her father, Timoteo Mendieta Alcalá. Timoteo, 41 years old, was a butcher, president of the local union, and father of seven. Upon gaining entrance to the house, the men arrested Timoteo and took him to a makeshift prison where he was beaten and put through a military tribunal. He was convicted of having given ‘aid to the rebellion’, that is, fighting for Spain’s democracy during the Civil War (1936-39). He was executed against the wall of the Guadalajara civil cemetery on 15 November, and buried in a mass grave. Ascensión blamed herself for her father’s death. She spent the rest of her life fighting for the right to exhume and rebury his body in accordance with her family’s wishes – not his murderers’.

The tragedy of Timoteo, and the other 23 people executed and buried alongside him, was a common story. By the end of the Spanish Civil War, more than 500,000 Spaniards had died, including an estimated 120,000 to 140,000 killed in extrajudicial executions – a purge of progressives, democrats, artists, teachers and the unlucky. During the immediate postwar period, more than 400,000 people were imprisoned, at least 20,000 of whom were executed. Hundreds of thousands more likely died while incarcerated, from neglect and disease.

The almost 40-year dictatorship that followed (1939-75) ensured that General Franco’s power infiltrated every aspect of Spanish society. He was relentless in punishing and repressing the defeated republicans – supporters of the Second Spanish Republic. Franco’s regime enacted a series of economic policies that effectively created second-class citizens. War widows and orphans, or those wounded on the Francoist side, received pensions or jobs, while their republican counterparts received nothing. The regime seized the property and assets of republican families, crushed unions, declared strikes to be acts of state sabotage, and purged ‘Leftist’ professions. These economic policies left most republican families in abject poverty.

In a particularly cruel form of psychic violence, the regime also banned all death rituals, including any kind of public mourning for those who died on the republican side during the war and those executed during the immediate postwar era. Simple markers of respect for the dead, such as placing flowers on unmarked graves, had to be done secretly, for to do so publicly was to risk one’s life. During my time in Spain, I heard a story of a widow who, after having her life threatened for erecting a memorial that was destroyed multiple times by the local police, scattered seeds over what she thought was her husband’s grave. Every spring since, for more than 80 years, a flood of lilies sprouts up over the hillside. A beautiful, but silent, protest.

After Franco’s death in 1975, the Spanish political elites decided, in the hope of maintaining political and economic stability, to pass what came to be known as ‘the pact of forgetting’. This agreement, made between the Right and the Left, asserted that the atrocities that had occurred during the Civil War and the Franco regime were to be forgiven and forgotten. This institutionalisation of sanitised silence preserved the status quo of victors and losers. Some victims’ families, like that of Ascensión’s, were able to finally place a headstone over the mass grave they assumed held their loved ones. But many more were left with nothing but fading pictures and deafening silence from their government. For almost 30 years, the Spanish population internalised the ‘pact of forgetting’.

Then, in the new millennium, the forensics-based human rights movement reached Spain. The silence that had long kept away the past began to break down, and those who had been killed by Franco spoke once again.

What is forensics-based human rights? How does it work? And, most importantly, how does it shape collective memory in cases such as Spain’s?

In its most immediate form, the forensics-based human rights movement’s objectives are simple: to help families find, recover and rebury their missing loved ones, and to offer scientific certainties about what happened in moments of state terror, war and genocide. In a longer view, it also gives human rights activists the possibility of challenging dominant histories of violence by providing new truths that emerge alongside the technical work of recovering and identifying remains. Forensics-based human rights is a scientific movement focused on uncovering the real stories of violent and chaotic pasts.

Despite the potential progress offered by this movement, the countries that require the services of forensics-based human rights are reckoning with rips to the societal fabric so deep they seem endless – and often, for the victims’ families, they are. This level of destruction to the social contract leaves countries in a complicated balancing act between the raw emotions created by the violence, and the need for political and economic stability. Throughout the scholarship, how best to transition out of war, genocide or authoritarianism is deeply debated. Over time, the preference for amnesty and silence evolved into following the calls for truth, reconciliation and legal justice for past instances of state terror, war crimes and genocide. In practice, of course, the success of these different paths varies by country and situation.

For many victims’ families, this meant the chance to have a funeral for a lost father, to rewrite historical records

Along with calls for truth to be included in transition politics, the influence of science and technology has also grown. This has much to do with the global forensics-based human rights movement’s origins, which rose out of the ashes of Argentina’s last and brutal military dictatorship. During the democratic transition in 1983, two human rights organisations – the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (which goes by the Spanish acronym EAAF), and the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo – cultivated a new and powerful alliance between human rights activism, forensic anthropology, and emerging blood testing capabilities, such as DNA. This gave rise to a new social movement that relies on the power of science to offer victims’ families and post-conflict/post-authoritarian societies new ways to process societally violent pasts.

The promise of forensics-based human rights, however, is not solely about identifying remains. It also encompasses more nuanced understandings of what justice means at the individual, family and societal levels. For many victims’ families, this meant the chance to have a funeral for a lost father, to publicly grieve, to rewrite historical records, all of which can create lasting changes to historical memory. These new forms of justice can be particularly poignant in cases where victims do not have access to legal justice due to amnesty laws, the passing of time, or uninterested governments that benefit from silence. The forensics-based human rights movement offers the chance for other voices outside of the state, due to the perceived legitimacy of science, to become narrators of past violent histories. The movement has spread across the globe, from Latin America to Africa, Europe and, recently, to the United States.

How societies reckon with their past is always complicated. Collective memory does not reflect any ‘objective representations’ of history. Instead, it is a messy combination of the present moment’s hierarchies, identities, and moral and emotional relationships to the past. Collective memory is like layers of sediment shaped by countless variables including emotions, power relations, culture, storytelling, and the passing of time. Of course, those holding privileged statuses, such as politicians, often have greater opportunities to advance ‘official’ accounts from which they benefit. This is especially true in societies that have suffered societal ruptures related to political violence, war or genocide, as some governments have a stake in purposely silencing violent pasts. Scholars such as Claire Whitlinger and Eviatar Zerubavel have argued that this form of silencing destabilises social solidarity by threatening the open communication that forms the foundation of democratic political cultures.

State-imposed silences, though successful for a time, are not impenetrable, and are often vulnerable to countering techniques. Those attempting to contest memories of state violence, such as human rights workers, need to be seen as legitimate to be heard and taken seriously. As the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu noted in 1982, the success of actors often depends on the ‘authority of the speaker’. As such, social actors putting forth counter-memories of state terror and violence must be seen as reasonable and not oriented by revenge or corrupt purposes. This is especially true in high-intensity situations, such as a transition to democracy or a rupturing of state-imposed silencing.

So how can a movement find a voice that is seen as both legitimate and not oriented by political animus? Social movement scholars have long argued that framing – using interpretive schemas to define, understand, and negotiate experiences within a social environment – intensify the cogency of a movement’s arguments. What resonates as authentic is often tied to the movement’s goals and claims, and can be produced through individual activists, their representation of beliefs, and their relationships (or lack of relationships) with other groups or institutions. Throughout my research on the global forensics-based human rights movement, I have found it to be particularly successful at navigating difficult memory terrains by framing their work in two ways: through the rights of families, and through depoliticised science.

But let us take a step back. States that use disappearances, arbitrary executions and unmarked graves do so to terrorise and repress resistance to their authority. As such, searching for a person who has been disappeared by the state is itself an act that contests state power. So, the forensics-based human rights movement must position itself as being about the rights of families to find their missing – not the politics that led to the disappearing in the first place. The focus is on the belief that all families have the right to know what happened to their loved ones and, if that person is no longer alive, that they are then buried in accordance with their families’ cultural and religious beliefs. Activists, by leading with the ‘rights of families’ framing, centre their movement around the deeply human need of families to understand the fate of their kin, as opposed to emphasising the politics of the violence. This is one aspect to their depoliticised approach.

The complementary side of this framing is that forensic science is the medium to achieve the rights of families because it is seen as the arbiter of truth. The science itself, whether it be exhumations or DNA testing, has no political agenda. The findings are just outcomes of scientific methods and practices. This is an effective strategy. Previous scholarship has shown that forensic science, and science in general (with the notable exception of climate science and, more recently, vaccines), is generally received by the public as being objective, truthful, value-neutral and free of political influence. Research has also suggested that television shows about crime have helped to reinforce the legitimacy of forensic science worldwide, which may explain why it has not been as easily dismissed as some other forms of science.

Forensic science is also more accessible because it is not necessary for non-professionals to understand the procedures that produce the scientific outcomes. They just need to understand the conclusions. Human remains with clear signs of violence, such as bullet wounds, ligatures or torture-induced fractures, are very powerful evidence as they can ‘speak’ clear truths. One does not need to have gone to university, or even be an adult, to understand what a bullet through the head means.

In Argentina, DNA testing has led to the recovery of the identity of at least 130 missing children

To put it in positivist terms, the simplicity of some forensic outcomes relies heavily on verification: someone shot this other person in the head and then they died. Other research on forensics-based human rights activism has shown that, once activists provide scientific evidence, such as DNA identifications of bodies in mass graves with 99.9 per cent accuracy, or forensic proof of torture, it can be difficult, if not impossible, for rivals to reasonably argue that the activists’ version of violent pasts are false or tainted by politics. Of course, there are rare examples, such as the complicated case of Bosnia, where underlying and historical tensions have been used to discredit or ignore forensic findings; see Sarah Wagner’s book To Know Where He Lies (2008) for a brilliantly nuanced analysis of the Bosnian case and its difficulties.

Since its inception in the mid-1980s, the global forensics-based human rights movement has become an integral tool in human rights investigations across the world. Its success can be measured a few different ways. In terms of legal justice, hundreds if not thousands of perpetrators worldwide have faced justice, whether in an international tribunal or in their home countries, based on the scientific findings of forensics-based human rights.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the International Committee on Missing Persons has identified more than 70 per cent of the missing killed during the genocide, and they have painstakingly put back together many of these remains. These findings were used in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to prove the crime of genocide. In Argentina, forensic science has long been associated with the human rights movements after the fall of the dictatorship in 1983: DNA testing has led to the recovery of the identity of at least 130 missing children. It has also been used in the court of law to hold many of the former regime accountable for their crimes against humanity. Forensics-based human rights blocked the perpetrators from completing their intention of fully erasing their victims from the earth.

In Spain, the ‘pact of forgetting’ remained in force until the year 2000, when the first scientific exhumation of the Civil War-era dead occurred. This was a watershed moment. A historical memory movement, grounded in forensics-based human rights, exploded across Spain as the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH), founded in October that year, began exhuming and commemorating Spain’s missing dead.

The ARMH (much like the EAAF and the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina) broke through the repressive silence of the past by using the ‘rights of families’ and ‘depoliticised science’ framings. It was able to do this by positioning itself as an organisation focused on the ‘rights of families’ to recover and rebury their long-missing dead. It then presented itself as the true narrator of Spain’s history, using science to ground its claims. By doing so, the ARMH has been able to sidestep many delegitimising strategies of the Spanish state.

The historical memory movement has had to brave a long-lasting conservative government that fought its efforts continually and aggressively. Yet the movement has stuck to the argument that all families, no matter how much time has passed, have the right to recover and rebury their dead – an especially powerful claim in a predominately Catholic country like Spain. Meanwhile, the organisations that led directly with politics – seeking a posthumous referendum on Franco – did not survive or else became online advocacy groups.

Naturally, there are those who do not like the depoliticised style of this movement. For some, and perhaps rightfully so, the depoliticised approach sanitises the politics of the victims too much: their ideologies, morals, and the reasons they died. This critique is valid. But this is not a zero-sum game. Both have their role in ongoing memory and justice pursuits. If anything, the depoliticised approach creates new opportunities to have overtly political, moral and justice-oriented conversations.

After the death of Franco, Ascensión Mendieta Ibarra continued to try to acquire permission to exhume her father, but that was difficult due to the circumstances of his burial in a municipal cemetery. Her battle to recover her father led her from one international court to another, and then all the way to Argentina. There, in her 80s, she testified in front of Judge María Romilda Servini de Cubría who was investigating Franco’s crimes. This was possible because of Argentina’s application of the international law of universal jurisdiction, which posits that any state can claim the authority to prosecute and adjudicate ‘core international crimes’, such as crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide, without having any personal, national or territorial interest or connection to the crime in question. After much legal wrangling, Judge Servini de Cubría mandated an order for the exhumation of Ascensión’s father, Timoteo.

After two different exhumations and a bitter fight with the local government, Timoteo was identified through DNA testing provided by the EAAF in early June 2017. On 2 July 2017, he was reburied surrounded by mourners waving republican flags. His family and members of the association walked alongside the casket; the Spanish press covered the funeral. As the casket was lowered, draped in the flag of the Second Spanish Republic, Ascensión threw republican-coloured purple, yellow and red carnations onto his grave, sobbing: ‘My beloved father, here you are finally. What a shame! My God, what a shame!’ She observed the crowd and said: ‘Thank you all for coming on this sad day.’ Then someone yelled back: ‘Thank you for fighting!’

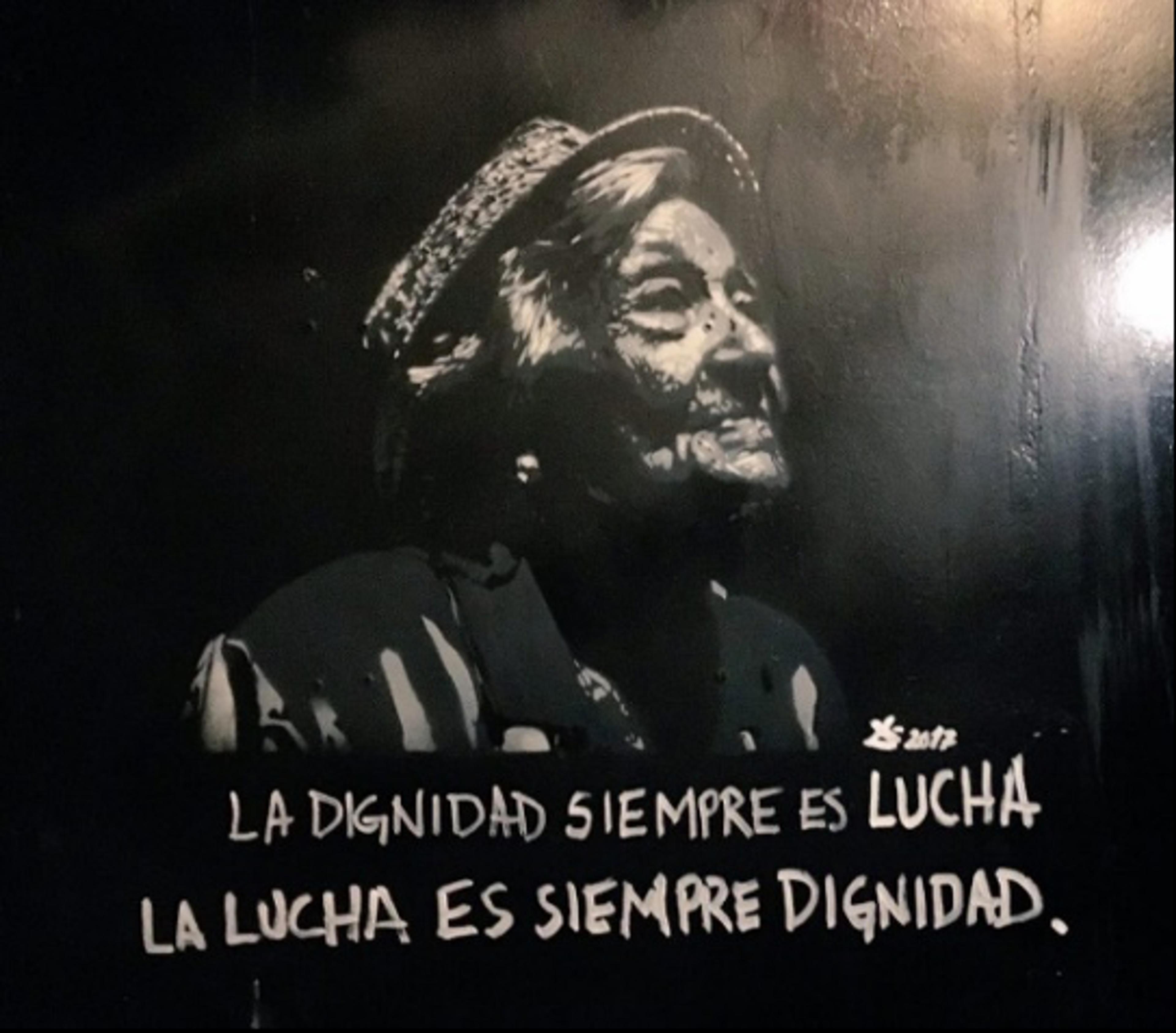

Due to these exhumations, an additional 100 people were also recovered. The local government initially requested that these bodies not be returned to their waiting families, but instead kept in the oblivion of their mass graves. It was only after an international outcry and the hacking of their city offices by the hacktivist organisation Anonymous that the city officials relented, and the bodies were returned to their loved ones. Ascensión continued to fight for others to recover their family members until she died in September 2019. She was buried alongside her father, as per her final wishes. Her image has also become part of political cartoons and street graffiti in Madrid.

‘Dignity is always a fight. The fight is always dignity.’ Graffiti in Madrid.

The effect of forensics-based human rights in Spain, including the work of the ARMH, cannot be underestimated. Local municipalities, such as the Basque, Catalan and Andalusian regions, have all implemented laws that address Civil War and Franco regime atrocities, with each of these regions supporting or creating their own forensic teams to investigate local mass graves. Since 2000, more than 9,000 bodies have been exhumed. The impact on the families is immeasurable; the impact on society incalculable.

It is justice to not leave these violent wounds festering, but to bring them into the open where they might heal

The movement has also been credited with helping set in motion the change in the dictator’s final resting place. In October 2019, the socialist government, after working with a commission that included prominent members associated with Spain’s forensics-based human rights movement, exhumed the body of Franco from the fascist mausoleum celebrating the Francoist cause, the Valley of the Fallen, near Madrid. He was moved to a municipal cemetery on the edge of the city, where the former dictator’s family has a crypt. On the day of the exhumation, there were no major disruptions or political backlash to Franco’s exhumation, contrary to what had been predicted.

This does not, of course, mean that all of Spain wanted the exhumation. On the contrary, one newspaper showed that nearly three-quarters of the conservative party voters believed Franco should not have been exhumed. Yet, one could argue that, for the future of the country’s democracy, the moving of the former dictator out of a massive mountain-top monument to a civilian cemetery reincorporates him into the realm of the ordinary citizen, and therefore opens him to a more critical remembering.

Most recently, forensics-based human rights have also intersected with premier Spanish filmmaking. At the end of Pedro Almodóvar’s latest film (spoiler alert), Parallel Mothers (2021), bodies recovered from a mass grave recompose from skeletal remains into recognisable human form. Almodóvar chose not to cast actors, but instead used real members of the forensics-based human rights movement in Spain, including the ARMH’s former lead archaeologist. The end of the film visualises what nuanced versions of justice mean in cases where legal justice is not accessible. It is justice to recover not only those lost to state terror, but also the larger truths about what happened during the violence. It is justice to allow families, no matter how generationally separated, to find each other again. It is justice to not leave these violent wounds festering in the dark, but to bring them into the open where they might heal.

Only time will tell how the global forensics-based human rights movement will continue to grow and evolve. It will be interesting to see if it can also make a difference in other cases of long-lasting impunity and silence in the aftermath of state terror. This would seem to be the case, as activists in Indonesia in the past two years have begun efforts to recover, identify and rebury the victims of the 1965 genocide and the Suharto regime.

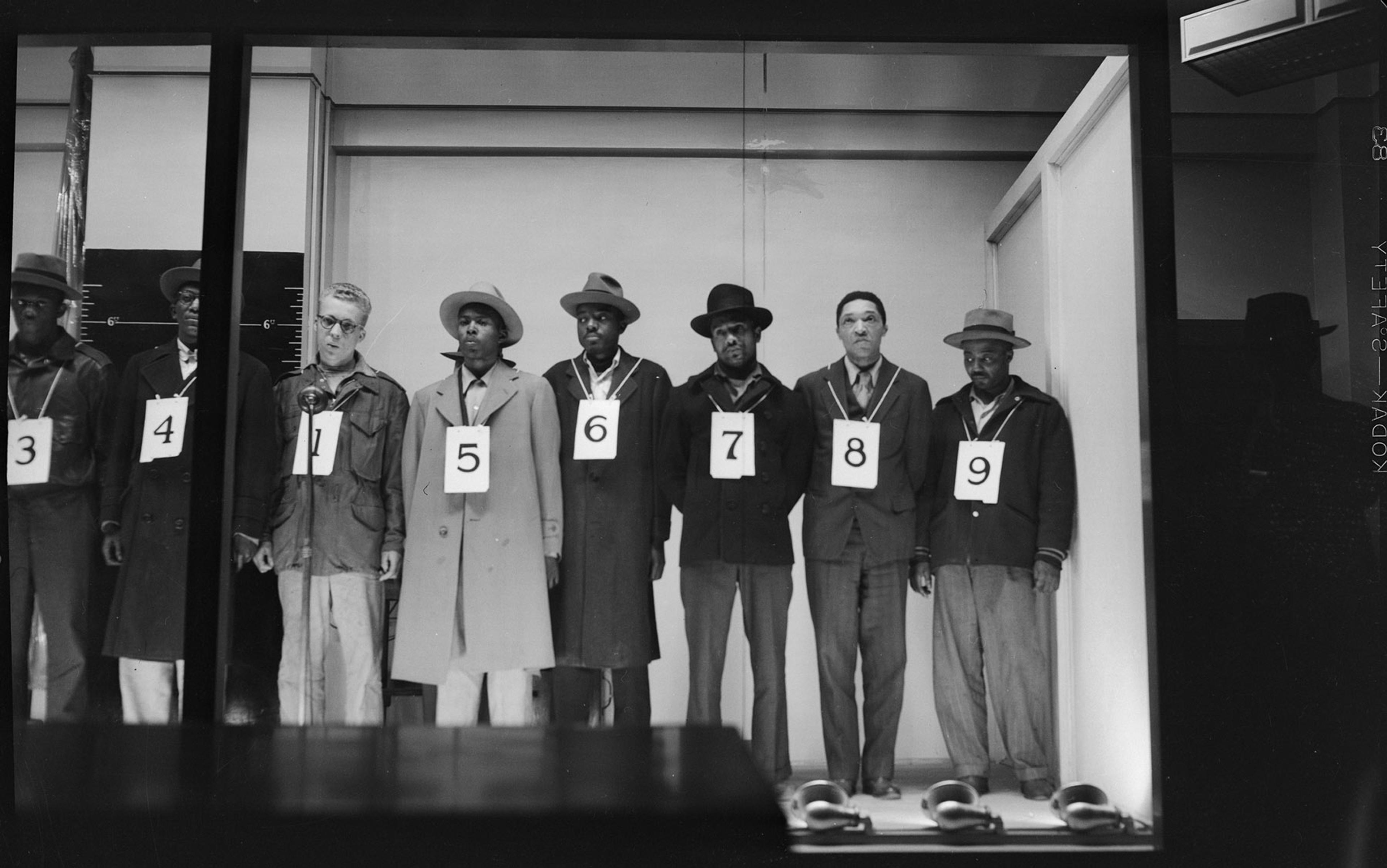

In the US, during the summer of 2021, forensic technicians began to exhume some of the presumed victims of the Black Wall Street massacre of 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which some 300 Black citizens were murdered by an enraged white mob over the course of two days. This marks the first time that forensics-based human rights have intersected with the long history of racial violence and terrorism in the US. Though it is too early to know the results of these exhumations, activists – and the three living survivors of the massacre, all over 100 years old – have been making efforts to receive reparations for those affected by the killings. In May 2021, at a hearing in front of the US Congress, one of the survivors, 107-year-old Viola Ford Fletcher, said: ‘I will never forget … I have lived through the massacre every day.’ For the survivors, what remains of state terror are its shattering and lifelong effects. Remembering what happened, even after they have gone, is the least we can do.