The new medium would spread half-truths, propaganda and lies. It would encourage self-absorption and solipsism, thereby fragmenting communities. It would allow any amateur to become an author and degrade public discourse.

Sound familiar? Such were the anxieties that the invention of printing unleashed on the world as 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century authorities worried and argued about how print would transform politics, culture and literature. The ‘printing revolution’ was by no means universally welcomed as the democratiser of knowledge or initiator of modern thought.

In 1620, Francis Bacon named printing, gunpowder and the nautical compass as the three modern inventions that ‘have changed the appearance and state of the whole world’. For others, this outsized influence was exactly the problem. A few decades earlier, the scholar William Webbe complained about the ‘infinite fardles of printed pamphlets; wherewith thys Countrey is pestered, all shoppes stuffed, and every study furnished.’ Around the same time, the pseudonymous Martine Mar-Sixtus lamented: ‘We live in a printing age,’ which was no good thing, for ‘every rednosed rimester is an author, every drunken mans dreame is a booke’. Printing was for hacks, partisans and doggerel poets.

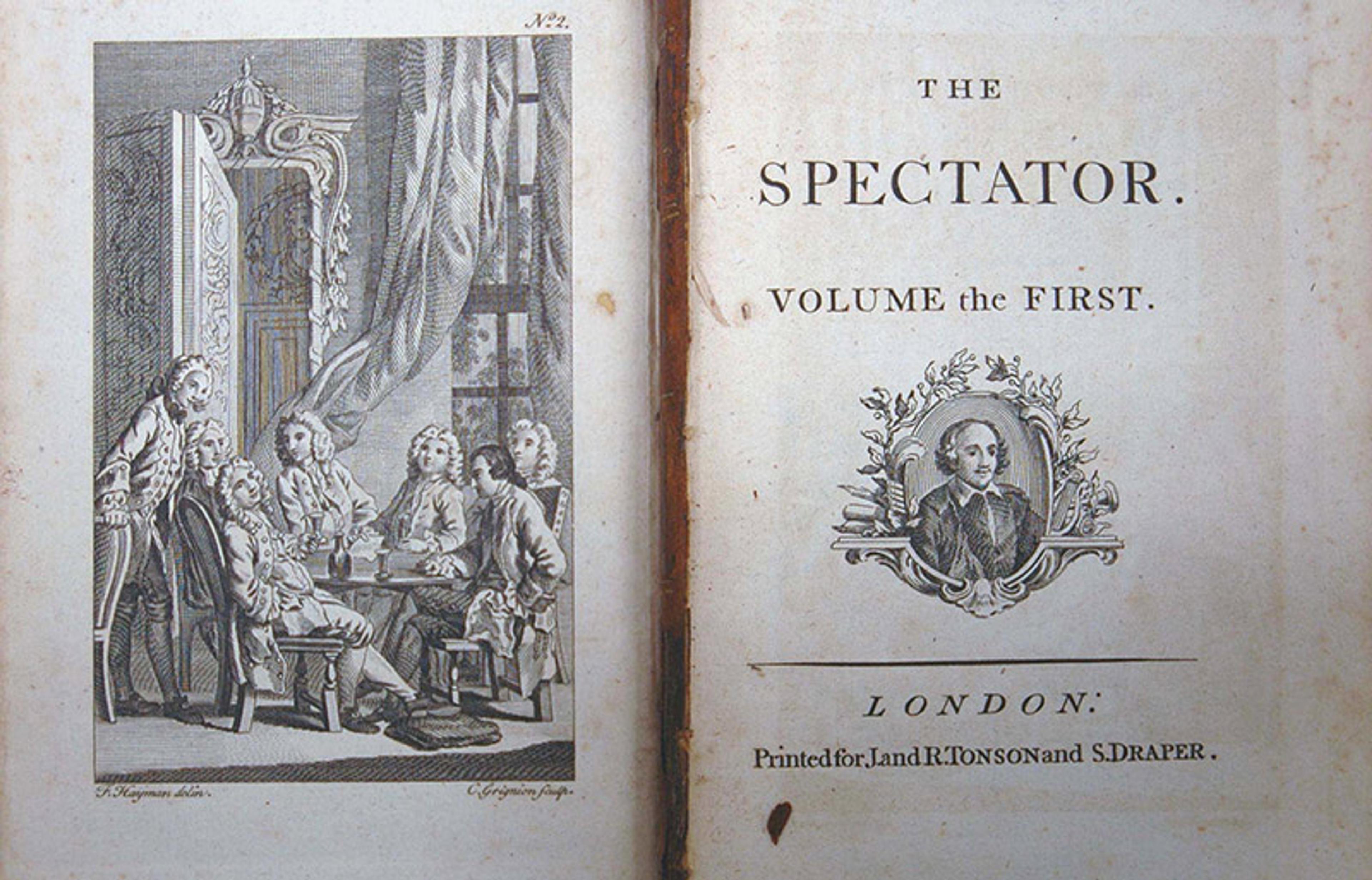

In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962), Jürgen Habermas argued that print enabled the establishment of an arena of public debate. Print first made it possible for average people to come together to discuss matters of public concern. In turn, their knowledge and cooperation undermined the control that traditional royal and religious powers had over information. Habermas pointed to the early 18th century as a crucial moment of change. At that time, newspapers and periodicals exploded in both number and influence. ‘In The Tatler, The Spectator and The Guardian the public held a mirror up to itself,’ Habermas noted of the impact of a trio of periodicals by the journalists Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. The new publications allowed readers to shed their personal identities as rich or poor, male or female. Instead, in print they could enter into conversation as anonymous equals rationally engaging with the topics of the day.

Addison himself was not so sure about the positive effects of print. In 1714, he wrote in The Spectator:

It is a melancholy thing to consider that the Art of Printing, which might be the greatest Blessing to Mankind, should prove detrimental to us, and that it should be made use of to scatter Prejudice and Ignorance through a People, instead of conveying to them Truth and Knowledge.

The Tatler included a character, the ‘political upholsterer’, who was so obsessed with reading the news that he neglected his shop, leading to bankruptcy and insanity.

Other contemporary commentators shared Addison’s misgivings. They would have been surprised by Habermas’s claims that print could create the ideal ‘public sphere of civil society’ consisting of ‘the critical judgment of a public making use of its reason’. Print could just as easily allow irrational, false and defamatory claims to circulate. While it is true that, over time, print came to seem the appropriate medium for public affairs, this was a process that took centuries. During that long transitional period, print borrowed from the associations of longer-standing media to establish itself as an authoritative source. In particular, the public sphere relied on the continuing power of what we now see as the quintessentially private form: the handwritten letter.

The frontispiece to a 1750 reprint of The Spectator, depicting seven honest readers discussing issues of the day. Courtesy Special Collections, the University of Otago, New Zealand

The first issue of The Spectator closed with an address ‘for those who have a mind to correspond with me’, at the printer ‘Mr Buckley’s, in Little Britain’. The public answered the call. The periodical, like its predecessor The Tatler, reproduced hundreds of readers’ letters, using them to represent alternative viewpoints, provide comic relief or just fill space. Collections of handwritten letters that readers sent to Steele and Addison remain at the British Library. The publication of letters fulfilled the claims of the magazine to represent a diversity of opinion.

Printed news also started out as, essentially, collections of letters to the editor. Newspapers did not routinely employ full-time reporters until the 19th century. At that point, the older meaning of ‘journalist’ – someone who keeps a journal – disappeared, and the word began to refer solely to news-gatherers. Similarly, interviews and in-person reporting did not become common until the 19th century. The earliest papers, in the 17th century, simply cut-and-pasted from letters that printers had received from correspondents around England and continental Europe. Some printers obtained letters by bribing officials with access to diplomatic correspondence. The first ‘foreign correspondents’ were diplomats who supplied intelligence offices and newspapers at the same time. In 1733, one magazine editor wrote that the meaning of the word ‘news’ was the collection of information out of letters that had arrived through the ‘Posts Foreign or Domestick’. When the wind blew toward the west, holding back ships travelling from the continent, there was no news.

Therefore, the earliest forms for public discussion of politics and literature in print presented themselves as epistolary conversations. Rather than negating the personalising effects of handwritten correspondence, they relied on them to make new forms of print seem familiar and understandable. The ‘print public sphere’ made its debut as a series of letters.

Intellectuals had been using letters as spaces for quasi-public engagement for decades prior to the emergence of newspapers and periodicals. In what some have called the ‘Republic of Letters’, scholars exchanged their literary and philosophical work and critiqued others’ productions. Similarly, the natural historians of the Royal Society debated experiments via letter, and sent out questionnaires with sailors travelling around the world. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, these epistolary exchanges migrated into print. The Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions – the world’s oldest scientific journal – and the first journals for book reviews both established themselves in part by re-publication of letters. The printed versions continued to use the letter format to signal their epistolary origins.

At the time, the reliance of the print public sphere on personal handwritten letters would not have seemed paradoxical. Early modern and 18th-century correspondents had a fundamentally different understanding of the letter genre than the one that prevails today. While we tend to see the space of the envelope as almost sacrosanct – making it a federal crime to open mail addressed to another – letters in the 17th and 18th centuries enjoyed no necessary connection to privacy. For one thing, ready-made envelopes did not come along until the 1840s. But even letters carefully sealed with string and wax were sometimes less than private.

Writers knew letters were part-public and part-private, and it shaped how they were written

The common practice would have been to read letters aloud upon receipt rather than to retire for silent, solitary perusal. Letters were also frequently written in groups with multiple correspondents adding notes or commentary. They were a kind of public property, conveying news from one place to another. They were also crucial to the functioning of business, dispatching orders and receipts, and would have been filed with other documents as general commercial papers. Writers knew this and did not presume the privacy of their letters when they were in transit. The English government had an entire office, the ‘private’ or ‘secret’ office, dedicated to opening and surveilling correspondence. In short, at any stage in its composition, transmission and reception, a letter might travel beyond the bounds of the one-to-one relationship that moderns imagine when we read a letter beginning ‘Dear X’, and ending ‘Signed, Y’ (or, in the period’s common subscriptions – ranging in degrees of intimacy and obsequiousness – ‘Your affectionate friend,’ ‘Your humble servant &c.,’ ‘Your worship’s most humble and obedient servant’).

The fact that writers knew letters were part-public and part-private shaped how they were written. Sometimes writers exploited the tension inherent in this aspect of their character. A popular work of epistolary proto-fiction, Charles Gildon’s The Post-Boy Rob’d of His Mail: Or, the Pacquet Broke Open (1692), for example, purported to be a collection of 500 letters stolen by a club of gentlemen engaged in a ‘frolick’. The letters included those from a gentleman to his mistress, an aspiring poet to the editor of the Gentleman’s Journal, a ‘Country Fellow giving an account of London to his Cousin in the Country’, and an apprentice to his mother complaining about mistreatment by his master. The collection showed the range of different and subtle ways that letters worked, from the sensational to the scholarly.

Letters have always helped people separated by distance to create a community of likeminded readers and writers. In recent years, scholars have often turned to the analogy of the digital network to explain the role that letters played in creating literary, intellectual, political and scientific communities. As the historian Lindsay O’Neill writes in The Opened Letter (2015): ‘networking was often the purpose of a letter … An examination of networks blurs the borders between the modern and the premodern worlds, between public and private spheres.’ By linking disparate people through decentralised networks that connected male and female, elite and plebeian, personal and professional, letters allowed people to see themselves as connected on a national and global scale.

Handwritten letters first helped people to imagine themselves as members of a public – as entering into conversation with other distant, perhaps even unknown writers whom they could reach only through this medium of text. As printed periodicals and newspapers began aspiring to connect groups of people in a similar way, they used the model of the epistolary network to train readers in how to use the new medium. Print enabled a wider, less personal and more unpredictable version of the public sphere, operating on a scale beyond the reach of manuscript. Yet letters lay behind this new version of the public sphere. Many news pamphlets, for example, styled themselves as correspondence: for example, a ‘Letter from a Gentleman in Town to His Friend in the Country’ was actually a discussion of London politics. In this way, the form of the letter familiarised print.

References to manuscript correspondence also offered the nascent news industry a version of what we might now call objectivity, making it seem as though printers were simply reproducing other people’s opinions rather than distributing their own – although news remained one-sided. Early news sources were frankly partisan. During the English Civil War, newsbooks representing either the Royalist or Parliamentarian perspective attacked each other with accusations such as that the author of the Mercurius Aulicus, a Royalist publication, ‘hath a commission to lie for his life, for the better advancement of his Majesties service’. The writers traded insults in an effort to convince readers.

In the 18th century, most newspapers enjoyed support from political parties. In the 1720s, the British prime minister Robert Walpole subsidised several different newspapers, although he was not successful in controlling the news. Because Parliament banned the reporting of speeches and note-taking in the galleries until the late-18th century, papers often relied on individual politicians for political news. Although papers came to support themselves through advertising and sales rather than government subsidy from the late-18th century on, it remained common into the early 20th century for newspapers in the UK and the US to be affiliated with particular political stances – a model that seems to be experiencing a resurgence today with cable and digital news.

Because letters imply the expectation of response, any reader could also be a source of news

During the ‘golden age’ of newspapers, from the 1940s to ’80s, mainstream media recognised and pursued an ideal of objectivity. It held that reporters should not advocate from a particular political stance but should follow a procedure that would present the most verifiably factual information available. Such an ideal and method was foreign to the writers of the 18th century; ‘objectivity’ took more than 300 years to develop in its modern form. However, earlier journalists used letters in a way that signalled an awareness of the problems with partisan reporting. Incorporating letters into newspapers and periodicals demonstrated that readers were getting a variety of perspectives – they were seeing the sources and could judge for themselves. This method was a different way of recognising the same problem, distrust of biased information, that the later professional standard of objectivity tried to solve.

Epistolary norms called for the writer not to impose their opinion upon the correspondent. Letters should present ‘news’ while allowing the recipient to form their own judgment. The common phrase that pieces of news were sent ‘for your information’ suggested that the writer would refrain from pushing a particular interpretation – whether or not they actually did so.

In newspapers, letters retained this sense of leaving interpretation up to the reader. Many printers would simply set incoming correspondence in type, leaving the news in the words of the letter-writer. This meant that references to ‘this city’ or ‘our king’ could be parsed only contextually, and might indicate foreign circumstances. In this way, the printer disclaimed an editorial position, implying that he or she was simply reproducing the words of others.

By addressing the reader through the second-person salutation (‘Dear You’), printed letters of news implied that anyone picking up the paper was a potential correspondent. And because letters also imply the expectation of response, this meant that any reader could also be a source of news – which often materialised when people wrote letters to the editor. The cyclical relationship of the epistolary network provided the logic for exchanges of printed news. Newspapers and pamphlets positioned their correspondents as sources of verification, rather than asking readers to trust the opinion of a single author, editor or printer.

Newspapers’ reliance on readers’ understanding of how to read and write letters could help to deflect some of the accusations against print. By reproducing letters, the print product could seem more of a continuation from existing media than a destabilising break with the past. Letters enabled a new scale of public communication by suggesting that print rested upon a manuscript foundation.

In the present-day shift to digital media and upheaval in the news industry, some idealise the printed newspaper and its ability to foster a unified understanding of the facts. Part of what has been lost, these commentators presume, is the ‘imagined community’ of newspaper readers. This sphere, as Benedict Anderson outlined in his classic study of nationalism in 1991, is one in which each individual reader is aware of the thousands of unseen others reading the same words in the same form at the same time (given the extreme ephemerality of any individual newspaper, which becomes outdated after 24 hours). In this way, the print public sphere allowed for citizens to debate topics of public interest but also implied arrival at a consensus, which would then be presented in the next day’s newspaper.

But the impact of print on public opinion was not only to establish a common understanding of the facts. It took hundreds of years for news reporters to develop the concept of objectivity, which did not necessarily mean that one was personally neutral but rather that one had followed a professional procedure to obtain unbiased information. And objectivity met with immediate objections from journalists who thought that an effort to present ‘both sides’ of every story might distort rather than reveal the truth. In recent years, political operatives have exploited this weakness in the concept of objectivity to present issues such as climate change and measles vaccination as having ‘two sides’, both of which must be represented in the media. For example, by treating climate change as a partisan issue rather than as scientific fact, ‘objective’ newspaper coverage has contributed to the perception that there is still legitimate scientific debate over humans’ impact on the environment. The result is not consensus but confusion for readers, compounded by, but not a direct consequence of, the decline of printed newspapers.

The public sphere was always perhaps more ideal than reality. Letters helped everyday readers understand how they could or should interact with print. But of course most people do not write letters to the editor; they consume other people’s opinions. And the personal, irrational or fake could never be banished from a world in which humans want to exchange gossip and scandal as much as – or perhaps more than – rational, enlightened debate. Understanding the complications of the public sphere 300 years ago illuminates how new media are again changing ideas about truth, fact and the news.