Scroll through the comments section of any popular YouTube video about Vietnamese history, and you will see admiration and respect from around the world for Vietnam’s anticolonial prowess. ‘I’m Nicaraguan and we went up against US imperialism several times and won. Vietnam was a huge inspiration to the Sandinistas! Long live a free Palestine!’ ‘The Vietnamese struggle for independence is one of the greatest David vs Goliath stories in the history of the world.’ ‘How Vietnam managed to endure Chinese domination, French colonialism, and US imperialism is beyond me. What a country.’

These sentiments reflect a heroic narrative of resistance, one that is effectively propagated by the Vietnamese Communist Party as Vietnam’s ‘official history’ in state-sponsored publications, schools, museums and elsewhere. The narrative goes like this: for the past 2,000 years, the Vietnamese people, unified by national pride, time and again expelled more powerful foreign invaders from their land. This tradition of anti-imperial struggle culminated in the rule of the Vietnamese Communist Party whose official political ideology is ‘Hồ Chí Minh thought’, named after the narrative’s protagonist, the first president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Inspired by a vision of communist revolution and drawing on a deep-seated tradition of Vietnamese resistance against Chinese domination, Hồ Chí Minh led the Vietnamese people to defeat Japanese occupation (1940-45) and French colonialism (1858-1954), as well as US imperialist invasion and their Vietnamese puppets (1955-75). The story evokes pride among Vietnamese people. As one Vietnamese translator put it: ‘Do you realise we are the only nation on Earth that’s defeated three out of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council?’

This romantic story is reflected not only in Vietnamese historiography by Vietnamese nationalists but also in classic works of Vietnamese history written in English by Westerners. Frances FitzGerald’s influential, Pulitzer Prize-winning book Fire in the Lake (1972), published before communist victory, proclaimed that the Vietnam War was not a civil war but, rather, Hồ and his followers represented the real Vietnam, carrying ‘on the tradition of Lê Lợi and those other Vietnamese heroes who waged the millennium-long struggle against foreign domination.’ For FitzGerald, the United States – in supporting Ngô Đình Diệm’s anticommunist regime – was on the wrong side of history and doomed to failure.

But in the past decade, scholars of Vietnam have been showing that the history of Vietnamese anticolonialism is not so simple and romantic. Vietnamese anticolonialism includes an array of competing nationalisms. A handful of competing theorists and activists in the first half of the 20th century became influential ‘thought leaders’ amassing thousands or hundreds of thousands of followers. They offered diverse ways of making sense of and responding to foreign domination, and proposed a wide variety of counter-versions of a Vietnamese national identity, in which Hồ’s vision was one of several possibilities. What makes Vietnamese anticolonialism especially unique is its use of national shame for productive, anticolonial, nation-building purposes.

Let’s begin with a simple but troublesome fact: early Vietnamese calls for resisting French colonialism often invoked Vietnam’s own colonial past, and proudly so. After gaining independence from a thousand years of Chinese rule in 939, the Vietnamese conquered the Cham and the Khmer people, taking their lands and participating in what we would call genocide as they marched southward in the 15th century to create their settler colonial state. Rather than look upon their colonialism with shame, pioneering nationalists such Phan Bội Châu ironically evoked Vietnam’s colonial past to motivate the Vietnamese to resist French colonialism. Without the heroic efforts of Vietnamese colonisers, he argued in 1907, Vietnam would be ‘no more than the lair of the people of Linyi, Ailao and Chenla [Champa, Laos and Cambodia].’ How could the Vietnamese now simply let Europeans take their land after their ancestors had fought Indigenous peoples to create their country of Vietnam?

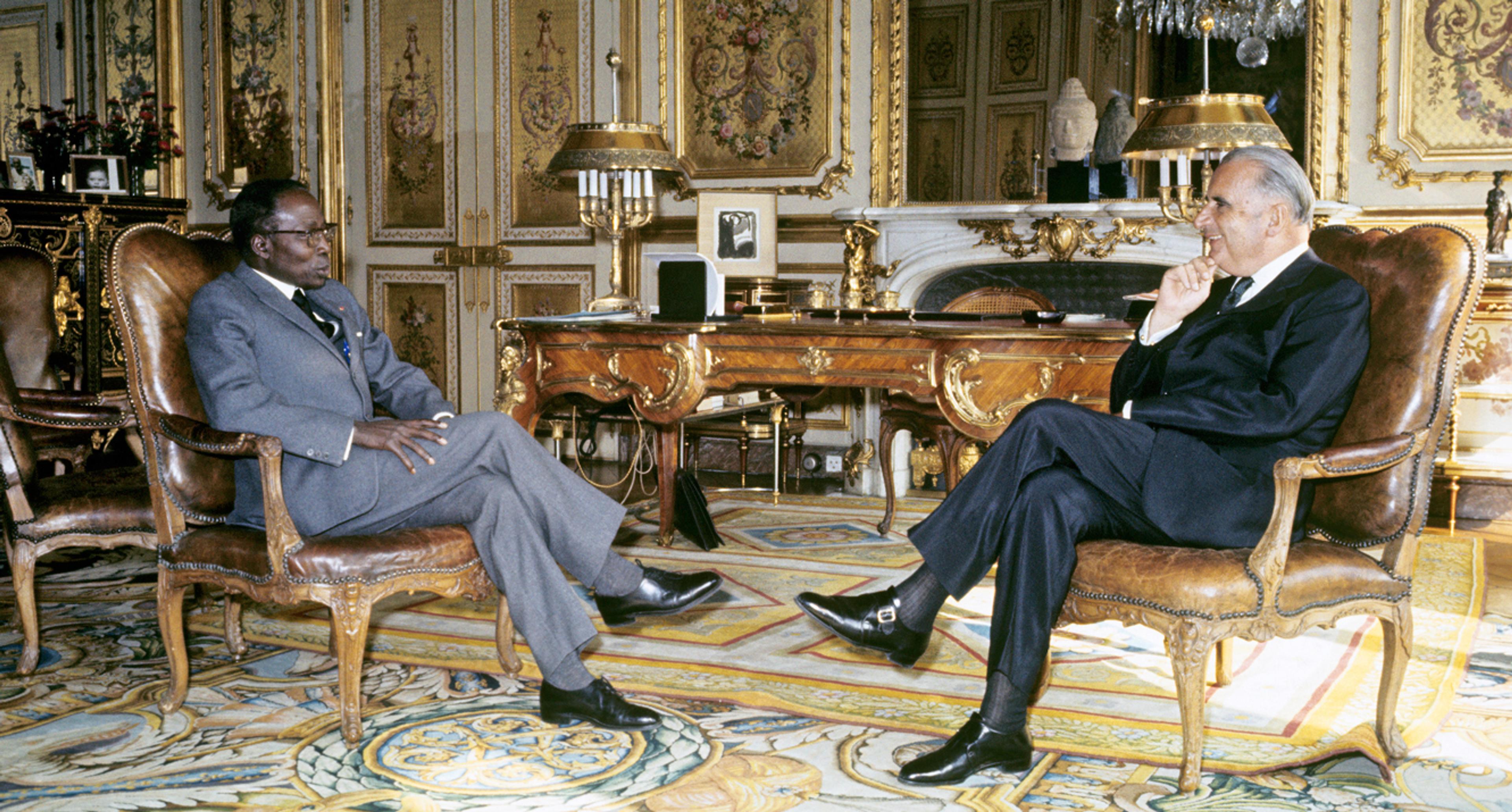

A view of Saigon in 1866. Public domain

And, contrary to the notion of a single, unified ‘Vietnamese people’, there has always been division. In the centuries after Chinese domination, civil wars persistently plagued the Vietnamese. Even after the emperor Gia Long unified Vietnam in 1802, civil strife continued up to the French invasion in 1858. As Phạm Quỳnh, a leading nationalist intellectual, put it in 1931, ‘since the end of the 18th century, internal dissension, including civil strife, has profoundly weakened us as the breaking up of our country combined with unrest have brought about such a state of affairs that could justify the French encroachment.’ And during French colonialism, Vietnamese figures influential in the public sphere had diverse, often conflicting ways of making sense of French colonialism, of how to respond to it and of the political ideology that should guide Vietnamese society after independence.

My father was 16 when he left Vietnam on a boat on the day the communists took over Saigon

Those ideological differences devolved into violent civil wars among Vietnamese, beginning not during the ‘Second Indochina War’ (1955-75) but earlier. Conflicts between Stalinists and Trotskyists persisted from the 1930s until the Trotskyists’ elimination in 1945. The ‘First Indochina War’ began in 1946 as a conflict between two sides – Hồ Chí Minh’s ‘Viet Minh’, a communist-led coalition of all Vietnamese (communists and non-communists) who opposed the French, and French colonisers – and ended with French defeat at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954. However, by 1947 and onward, the war against France simultaneously became a civil war between Vietnamese in the south, with some groups defecting to the French given their differences with the communists. And after French defeat in the north in 1954, Vietnam was divided into two countries: the ‘communist’ north and the ‘anticommunist’ south. The Geneva Accords allowed for a period of 300 days for Vietnamese to choose a side. About 800,000 moved from north to south, and about a third of that number moved in the opposite direction. Thus began the ‘Second Indochina War’. In the north, the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), supported by the Soviet Union and China, called it the ‘The Resistance War Against America to Save the Country’. And those in the south, the anticommunist Republic of Vietnam (RVN) supported by the US, called it the ‘War Against Northern Communist Invasion’. Americans call it, simply, the ‘Vietnam War’. It took the lives of 58,000 Americans and, according to the Vietnamese government, more than 3 million Vietnamese. Although the RVN lost and no longer exists, it still exists nostalgically in the minds of Vietnamese in the diaspora, such as my parents. The winning DRV unified the country and renamed it the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

For the past decade, I have explored various Vietnamese visions of decolonisation, motivated by a desire to examine my Vietnamese roots and also by a professional ambition to help broaden political theory beyond its European biases. My father was 16 when he left Vietnam on a boat (captained by my grand-uncle) on 30 April 1975, the day the communists took over Saigon. For those on the boat, the day marked the ‘Fall of Saigon’, and for the communists it was the ‘Liberation of Saigon’. My mother attempted to flee that day but managed to succeed only five years later. My parents met in California, where I was born. My aunts and uncles and the broader Vietnamese American community in San Jose, California where I grew up was deeply ‘anticommunist’.

My friends in high school and college were self-proclaimed Marxists who sympathised with the Vietnamese communists more than with my family. When a white, Marxist friend said to me that my family fled Vietnam because they ‘were lazy and didn’t want to work’, I felt offended. He couldn’t seem to acknowledge that they were fleeing persecution. And yet, as a Left-leaning student, I, too, found it difficult to sympathise with my own family’s ‘side’ of the Vietnam War. I once asked my aunt, who was in her late 70s: ‘What was your life like in Vietnam before the war?’ She replied: ‘It was so nice! We owned a big house. We had servants. They did everything, so we never worked. I read books in the garden all day. Then, the communists took it all away! They’re evil!’ It was difficult to sympathise with her as it seemed natural, not evil, to me that peasants would feel resentful toward people like my aunt. How could she not see it from the perspective of the communists?

In my efforts to learn more about Vietnamese history, the only material I could find in the public library and on my university course were US-made books, movies and documentaries about ‘The Vietnam War’. Watching them, I often felt frustrated at how the Vietnamese were portrayed. They were either victims (of the Americans, or of the communists, or of the refugee experience), villains (fascist dictators from the north or the south), or mere puppets of big powers (such as the US or the Soviet Union). In these portrayals, the Vietnamese were never thinkers. They never had complex motivations or complex answers to big political philosophical questions. In my final year as an undergraduate at the University of California, Irvine, I asked myself: were there Vietnamese political theorists that we in the West can learn from?

After I graduated in 2010, I moved to Vietnam to seek answers to my question and to recover the Vietnamese language (my first language until I was about seven years old). For eight months, I lived in Nha Trang, in southern Vietnam. For work, I taught English and, in my time off, I’d travel around the country. One thing stood out to me: the names on street signs. Major streets and schools were named after Vietnamese national heroes, from those fighting Chinese domination, to those fighting against French colonialism, to those fighting South Vietnam and the Americans.

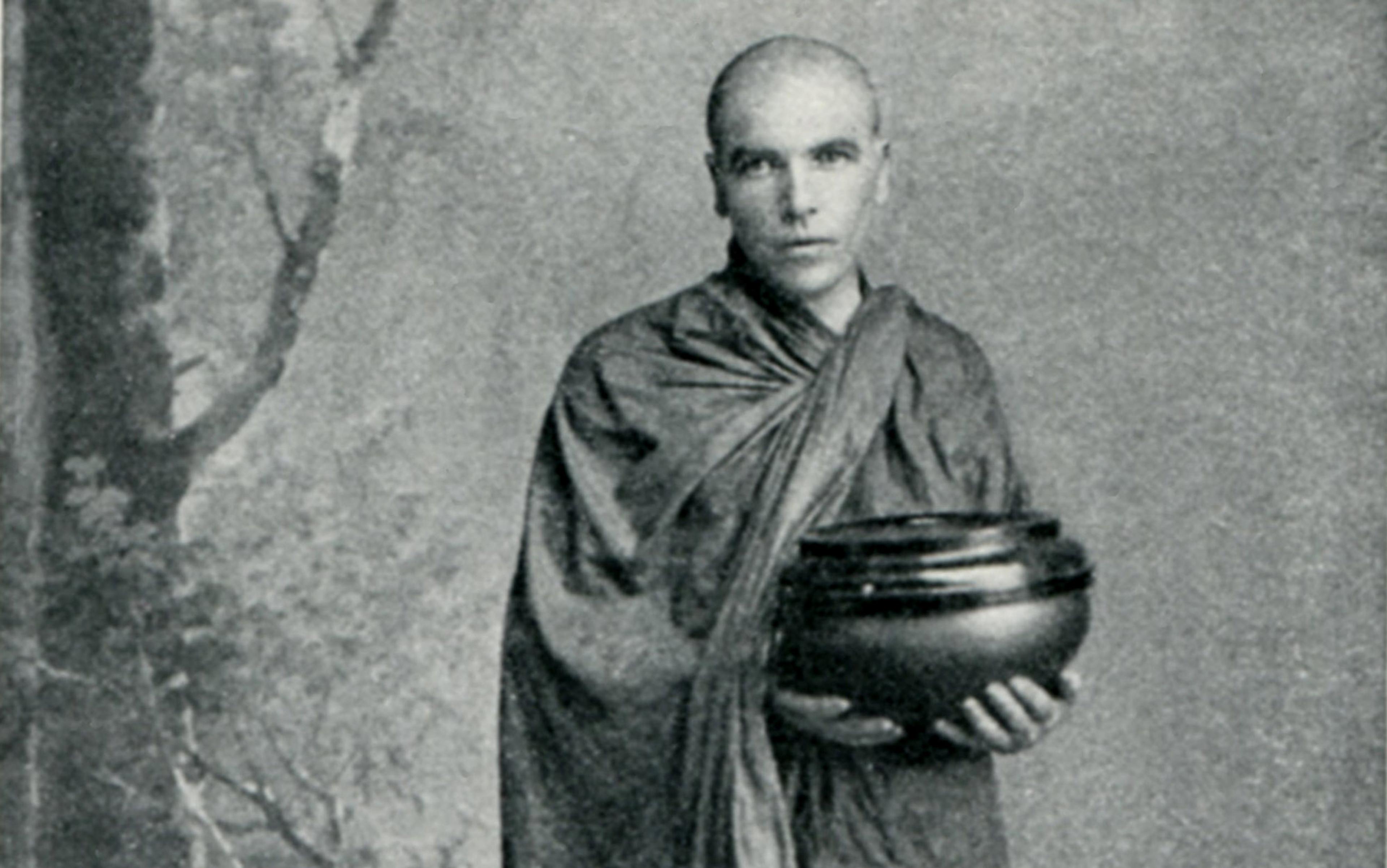

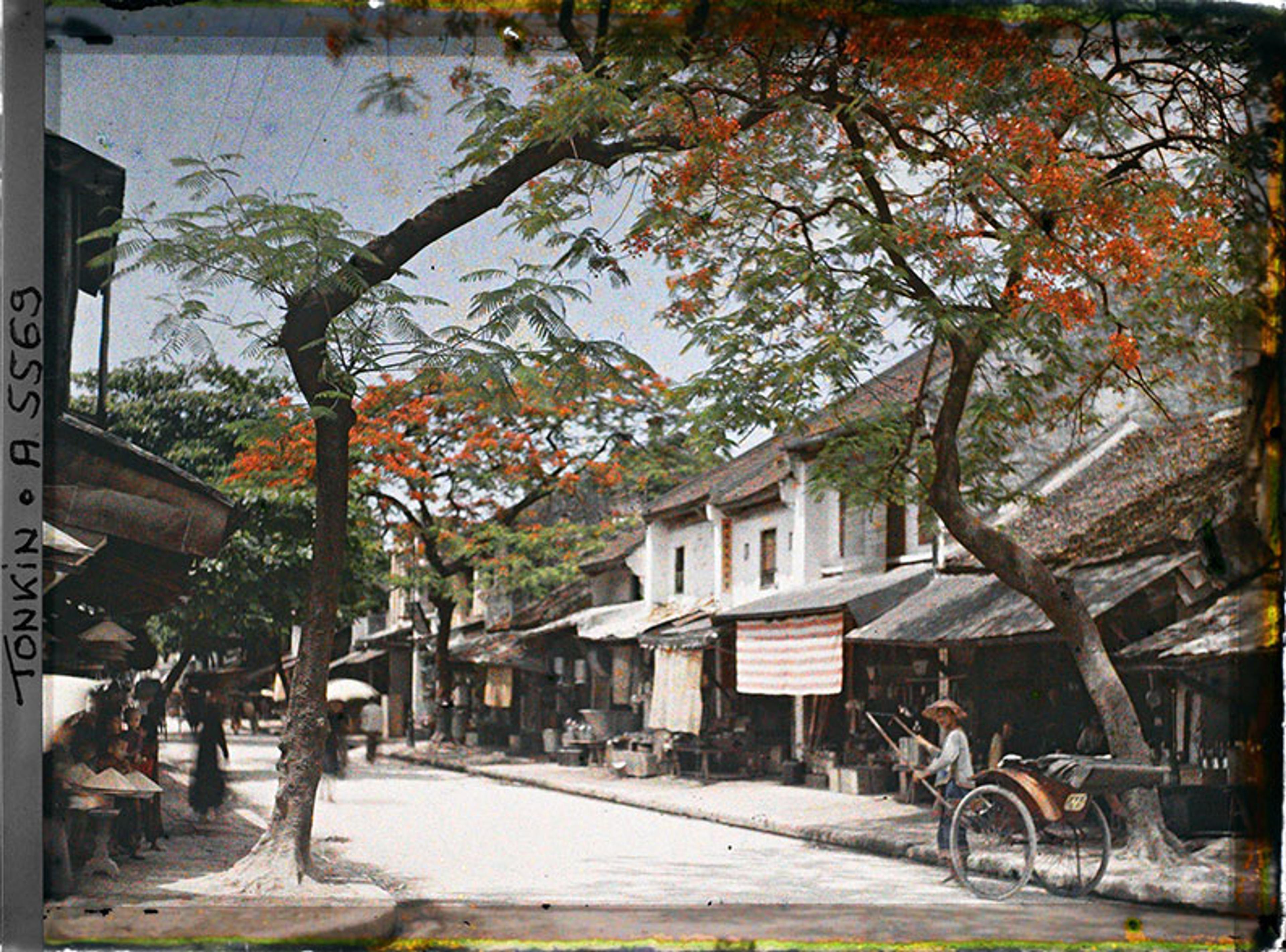

Rue Paul Bert in Hanoi. French photographer Léon Busy documented life in Indochina c1912-18 using the hand-coloured photochrome process. All photos courtesy the Albert Kahn Museum, Paris

A rickshaw beneath trees in the Rue des Ferblantiers, Hanoi, Indochina

A group of notables, seated in the interior courtyard of a house in Tonkin

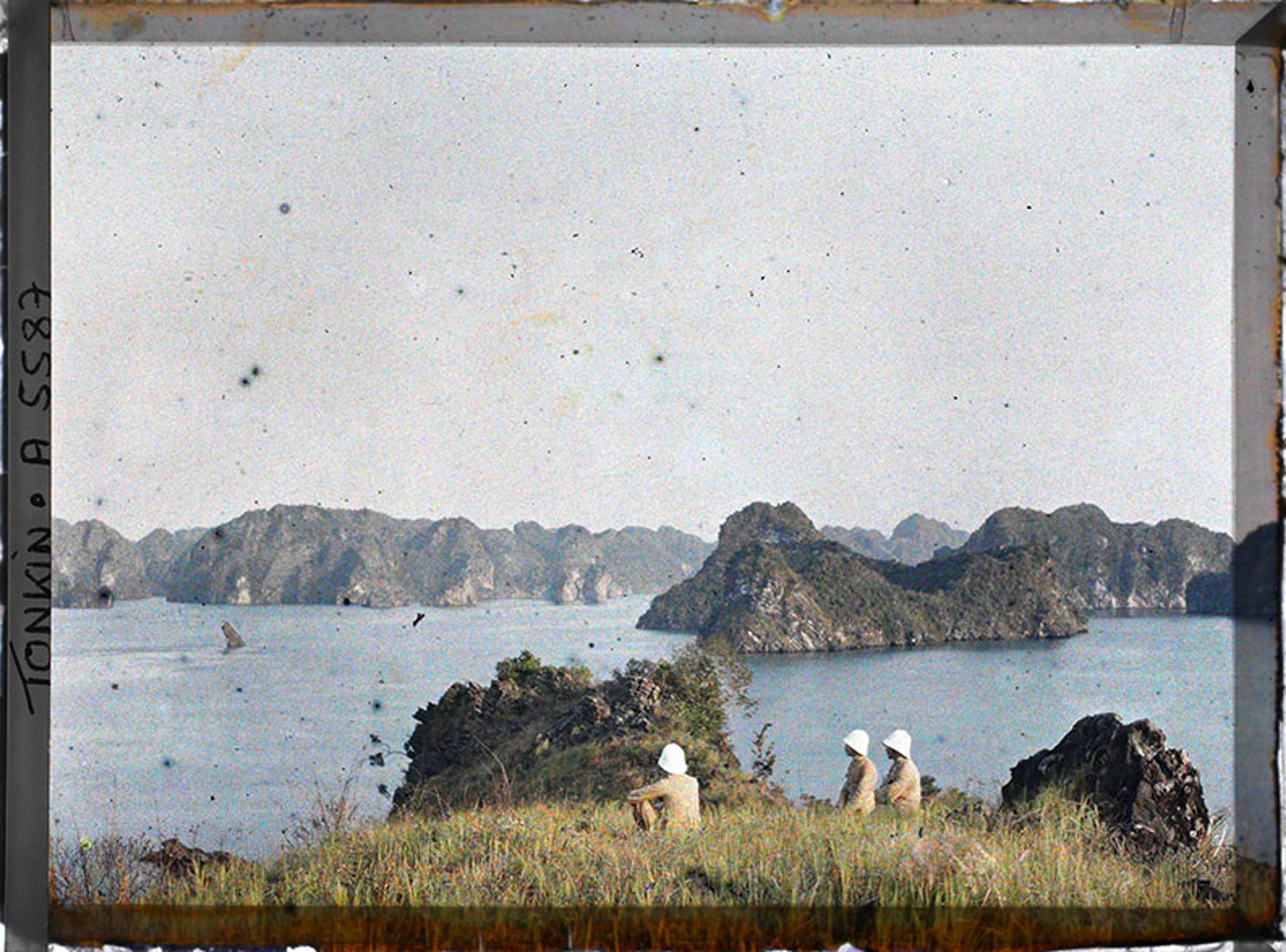

French colonial infantry officers overlooking Hạ Long Bay, Tonkin

Who were these figures and what were their thoughts? I was especially interested in the French colonial period, because – as a Vietnamese American with one foot in Californian punk-rock culture and the other foot in Vietnamese culture – I felt I could identify with those young Vietnamese intellectuals in the early 20th century who attempted to make sense of mentally inhabiting both ‘East’ and ‘West’. I wanted to know who were the most important, influential political thinkers of that time, and I wanted to read their thoughts. So I asked shopkeepers, street vendors selling pho, students, business people and teachers. I read books on Vietnamese history.

If these questions were universal, why were my books attentive only to how Europeans have answered them?

Shortly before moving to Vietnam, I asked one of my uncles who had fought for the South Vietnamese Army (the Army of the Republic of Vietnam): ‘The South Vietnamese were fighting against communism, but what were they fighting for?’ He replied: ‘Freedom and democracy.’ But in Nha Trang, as I read Hồ Chí Minh’s writings, I saw that ‘freedom and democracy’ (tự do and Dân chủ) were also the exact words that Hồ and his followers used to describe what they were fighting for. How could two sides use the same words to describe their goals and at the same time consider each other enemies?

These questions led me to an interest in political theory, in how people in conflict could offer different meanings to concepts like ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, as well as different answers to questions such as: what is a good life? Should society be thought of as a contract or a family? What values should we prioritise? Who should rule? These questions seemed universal: questions that anyone, anywhere, anytime should be able to answer. Later, I studied political theory in graduate school.

But, if these questions were universal, why were my books and courses on political theory attentive only to how Europeans have answered them? Until the past two decades or so, political theorists assumed that political theory happens in only treatises: written books with systematic, logical arguments. But over the latest generation, many have accepted that political theory also happens in speeches, letters, newspapers, pamphlets, wherever humans express themselves to make sense of what is happening in their world so that they can respond to it. With this broader understanding of where we can find political theory, we are now seeing scholarly work emerge about the political thought of people previously excluded from the field. It turns out that political thinkers from outside the West can challenge and enhance our Western conventional wisdom about political life, partly because there is at least one big difference between Western and non-Western political theory: the experience of European colonialism.

For the past 500 years, Europeans have conquered or colonised most of the planet at a speed and scale never seen before. Therefore, much of modern political thought in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America has been shaped by their experiences under European colonialism or domination. Thus, their big questions might look a little different. In addition to asking: ‘What is a good life?’ and ‘What values should we have?’, Vietnamese thinkers in the first two decades of the 20th century asked questions such as: how did these Europeans dominate us? Is European colonialism a law of nature, the strong dominating the weak, as social Darwinists might say? Or is European colonialism a result of capitalism, as Vladimir Lenin might say? How do we respond to European colonialism? What should we do with our traditional values given the influx of new ideas from Europe? And when colonisers racially abuse us, humiliate us or dehumanise us, how do we channel our indignation into productive political projects? How do we generate power among ourselves to resist colonialism or to do revolution? And what should the methods and goals of resistance and revolution look like? In short, what is the best vision of decolonisation?

In the late 19th century, anticolonial uprisings such as the ‘Cần Vương’ (Save the King) movement aimed to expel the French to restore the monarch. These movements were conservative, not revolutionary. The earliest Vietnamese intellectual responses to colonialism that began to consider revolutionary paths are best understood through the eyes of two of the most important nationalists of the early 20th century: Phan Bội Châu and Phan Châu Trinh. Two decades older than Hồ Chí Minh, both were the first to articulate a Vietnamese response to ideas from the West.

Châu’s goal was for the Vietnamese to see themselves not just as subjects of an emperor but as citizens of a nation

Like other young men and their fathers, Phan Bội Châu (1867-1940) devoted himself to studying for the civil service exams. But with French control over Vietnam complete by the turn of the century, they were beginning to doubt that the best life was to be a mandarin serving the Vietnamese emperor. At the time, social Darwinist explanations for Vietnam’s fall to the French prevailed among Vietnamese intellectuals, who had learned them from the writings of Chinese reformers adapting the theories of Herbert Spencer. It was Spencer who coined the expression ‘survival of the fittest’ and was, according to some scholars, ‘the single most famous European intellectual in the closing decades of the 19th century’. Only by the 1930s, among Vietnamese intellectuals, would Marxist-Leninist explanations for colonialism displace social Darwinism.

Phan Boi Châu, c1920. Courtesy Wikipedia

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Châu and Trinh were convinced that Vietnam was conquered because it was weak and France was strong, and that Vietnam had to find a way to strengthen as quickly as possible. Inspired by Chinese reformers such as Liang Qichao whom he had met while in Japan to learn of Japan’s modernisation process, Châu wrote essays, such as History of the Loss of Vietnam (1905). His goal was to persuade the Vietnamese to see themselves not just as subjects of an emperor but as citizens of a nation. As the first modern Vietnamese nationalist, he wrote about the French violating the country to make his readers angry so that they would develop a national consciousness of themselves as Vietnamese. He also tried to make his readers feel hope by writing utopian descriptions of what Vietnam could be in the future, if the nation worked hard enough: it could have buildings thousands of metres tall so they’d touch the sky. Châu wanted to motivate his readers to fulfil their duty of improving their nation. He had his works, originally written in classical Chinese, recopied and translated to quốc ngữ(Romanised Vietnamese), and then circulated clandestinely and read out loud to villagers.

Châu said that he was ultimately a failure, but he provided a nationalist framework that later thinkers would work from and develop in new directions. Initially, Châu, like the disbanded Cần Vương members that he sought to mobilise again in the early 1900s, sought to expel the French only to restore the monarch. But later in life, he turned against the monarchy and came around to revolutionary ideas of republicanism. This was likely due to the intellectual influence of his friend, Trinh.

Phan Châu Trinh, date unknown. Courtesy Wikipedia

Like Châu, Phan Châu Trinh (1872-1926) argued that the Vietnamese were conquered because they were weak. But, unlike Châu, Trinh also offered a more fully fledged political theory of how the Vietnamese could strengthen themselves. Also unlike Châu, Trinh travelled to France – where he lived for 13 years – and returned to Vietnam in 1924 to be the first to introduce the idea of ‘democracy’. He explained to his compatriots that they were weak because they forgot the teachings of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher. The solution, he argued, was for the Vietnamese to adapt a new idea from Europe called ‘liberalism’ (tư tưởng tự do) and the form of government he thought came from liberalism: democracy (dân chủ). Doing so, he believed, would improve Confucian methods of self-improvement in Vietnam. For political theorists who see ‘Confucianism’ and ‘liberalism’ as opposed, this is an odd claim. Yet, Trinh takes liberties in interpreting liberalism, romanticising it, downplaying its individualism, and imports the creative distortion to Vietnam to revive its own faltering tradition.

Châu and Trinh wrote primarily in classical Chinese. A younger generation of intellectuals, Nguyễn An Ninh and Phạm Quỳnh prominent among them, went to French-language schools, where they learned European ideas, and expressed their political and philosophical thoughts primarily in French. Nguyễn An Ninh (1900-43) was a passionate anticolonialist who was arrested five times by the French. He argued that the Vietnamese should stop parroting Chinese and Confucian ideas, and learn to stand on their own feet and think for themselves. The Vietnamese elite, he said, hung on to Confucian ideas like shipwrecked people hang on to a wooden raft. They should let go and swim for themselves. For Ninh, Indian and German great thinkers could serve as inspiration to create a new authentic Vietnamese intellectual culture. The Vietnamese must become great writers and artists to raise Vietnam’s status and dignity in the world, just as Rabindranath Tagore did for India. Tagore, Ninh explained, ‘besides his glory as a poet, … devoted himself to national education, creating for his students literary masterpieces in the Bengali language, the translations of which are scattered across Europe.’

Hồ saw Party cadres as akin to wise parents, and the people like children in need of moral development

In 1926, Phạm Quỳnh (1892-1945) attacked Ninh for having the wrong ideas. Whereas Ninh wanted the Vietnamese to let go of the ‘Confucian raft’ to swim for themselves, Quỳnh thought Vietnam needed Confucian ideas and that abandoning them meant the Vietnamese people would drown. Quỳnh used his journal Nam Phong (‘The Southern Wind’, 1917-34) to assert the value of Confucianism and Vietnamese national language and culture. He wanted to harmonise Eastern and Western ideas to create a new Vietnamese national identity. The dominance of Western power, science and technology was destroying the world, as seen in the destruction of the First World War; the solution was to balance it out with ‘Eastern Wisdom’. Perhaps naively, he argued that the wrongs of colonialism could be superseded with the passage of time if the French lived up to their own enlightenment beliefs.

As Ninh and Quỳnh put forth their exhortations in journals in Vietnam, Hồ Chí Minh was abroad for three decades, from 1911 to 1941. Through his associations with socialists in France in the early 1920s, Hồ would come to see Lenin as Vietnam’s guiding light. He would take his knowledge of Confucian morality and fuse it with Leninism to form what he called ‘revolutionary morality’. According to this morality, Communist Party leaders must first remould themselves through criticism and self-criticism, and only then could they guide the masses towards communist revolution. Hồ saw Party cadres as akin to wise parents, whereas the people were like children in need of moral development. And he thought it democratic because the people are simultaneously the country’s masters while the Party is their servant.

Although Hồ’s vision inspired many, it also produced what some communist leaders would eventually admit were ‘errors’. From 1954 to 1956, the party implemented land reforms in which land was taken from landlords and redistributed to poorer peasants. Yet, General Võ Nguyên Giáp admitted to errors such as using ‘excessive repressive measures’. To some anticolonialists, the communists were becoming too dogmatic, authoritarian and fanatical after they won independence. One such critic was Nguyễn Mạnh Tường (1909-97), whom the Communist Party in the mid-1950s forced to retire from practising law due to his support for democracy and rights. To theorise what was going wrong with the Communist Party, he quoted the 16th-century French essayist Michel de Montaigne, arguing that the Vietnamese communists must embrace freedom of thought and discussion: they ‘must neither shut themselves up nor lock themselves in a closed world, but open themselves to the “commerce of men”, “rub and polish our brains by contact with those of others”.’

The romantic communist narrative that has been influential around the world portrays a proud Vietnamese people always resisting their colonisers. But key anticolonial figures, particularly in the early 20th century, were constantly using shame to goad their people into anticolonial action. In 1907, Phan Bội Châu wrote to his countrymen:

Those whom I blame most deeply are my people themselves.

Phan Châu Trinh lamented:

[I]t is a shame that our people … cannot look after their basic personal needs and prepare for their old age, let alone think of society or humanity. How could we not respect the Europeans if they are so superior to us?

Nguyễn An Ninh said:

If we take stock of the purely literary and artistic achievements that have been produced here, the intellectual legacy of our ancestors would certainly be meagre alongside the heritages of other people … Today when India and Japan are producing thinkers and artists whose talent and genius shine forth as brightly as those of Europe, Vietnam is but an infant that does not yet even have the notion or power to grope toward a better destiny and genuine deliverance.

Phạm Quỳnh scolded young people:

The youth lack personal power, strength, temper of character, that vigour of spirit and that moral virility.

Hồ Chí Minh declared in a letter:

Instead of blaming others, I think it is more reasonable to blame ourselves. We must ask ourselves: ‘For what reasons have the French been able to oppress us? Why are our people so stupid? Why hasn’t our revolution succeeded?’

And, after the French were finally expelled in 1954, Nguyễn Mạnh Tường shamed revolutionary leaders for having ‘alienated their individuality and even their personality, replacing it with a double of themselves whose reactions are remote-controlled from the outside.’ These thinkers attempted to shame their compatriots into productive, anticolonial, nation-building projects.

A thousand years of Chinese domination meant the shame of taking almost everything from China

When colonised peoples express shame, postcolonial theorists tend to dismiss it as a kind of ‘internalised inferiority’, ‘false consciousness’ or ‘colonial mentality’. However, these thinkers were ashamed of their people on their own terms and used such shame for productive, anticolonial purposes. They knew that it wouldn’t be enough to point out that the French were exploiting and abusing their people. That might be enough to spark anger, but it wasn’t enough to get the Vietnamese to devote themselves to long-term projects of changing their society – their habits, values and culture – for revolution. For them, shame could be more useful, a way to goad their compatriots into action. Shame can make one want to change, to become better, to overcome one’s inadequacies, to rise to the occasion.

Postcolonial theorists have also assumed that colonialism destroys ‘original’ Indigenous traditions. But this overlooks the fact that some colonised people themselves were unsure about the existence of their own ‘Indigenous’ traditions. In Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Frantz Fanon defines all colonised peoples as those ‘in whom an inferiority complex has taken root, whose local cultural originality has been committed to the grave.’ But the anticolonialists discussed above were conscious that a thousand years of Chinese domination meant the shame of taking almost everything – philosophy, political systems, literature, language – from China. They struggled to identify an Indigenous intellectual heritage to proudly call their own.

Yet, rather than despair, Vietnamese anticolonialists used self-shame and self-critique to motivate their compatriots to recreate their nation anew. A battle of ideas raged among Vietnamese anticolonialists. How can the Vietnamese construct an intellectual heritage to be proud of? What values should the nation uphold? From whom should the Vietnamese find inspiration? New research on Vietnamese intellectual history has shed more light on the complexity of these debates, further complicating our understanding of the conflicts in Vietnam. For example, recent work has examined how Ngô Đình Diệm, the first president of the Republic of Vietnam, was not just anticommunist but also anticapitalist, as he was inspired by the ‘personalism’ of Emmanuel Mounier, a French Catholic philosopher who was sympathetic to Marxism. On this view, the Second Indochina War is better understood as a war not between communists and anticommunists but between two kinds of anticolonial communists: Stalinists and Marxist humanists. Today, one might say that Hồ Chí Minh’s vision – or, perhaps more accurately, the Vietnamese Communist Party’s interpretation of Hồ Chí Minh’s vision – has emerged as the winner of this battle of ideas. But one may also say that such debates continue to persist.