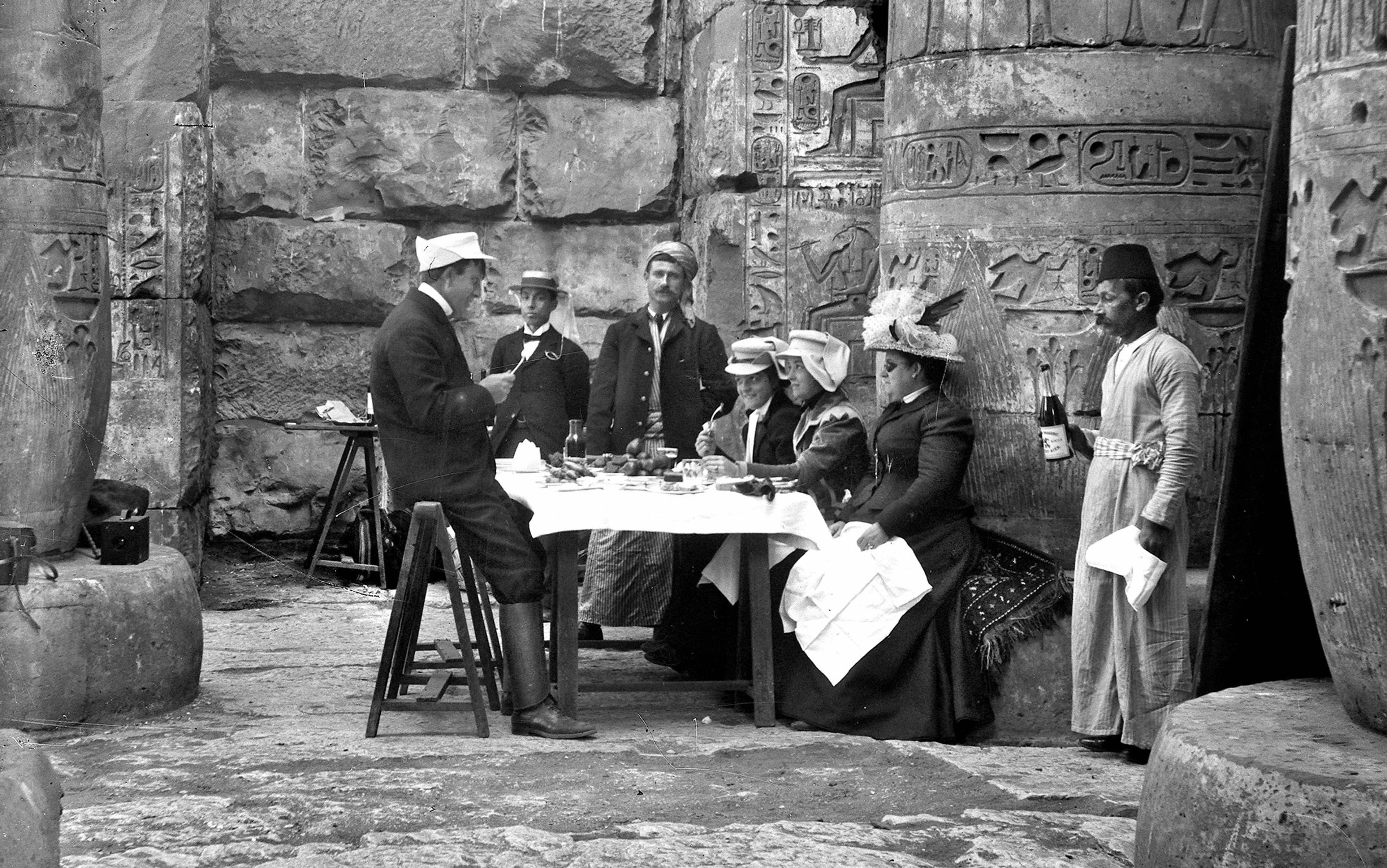

March 2022. Invading Russian forces have captured the city of Melitopol in the south of Ukraine, one of few successes amid the failure of the wider invasion of Ukraine. In the city’s Museum of Local History, a collection of at least 198 golden artefacts is deliberately and systematically pilfered by the occupiers. This is not the opportunistic, haphazard looting of individual soldiers. According to eyewitnesses and local officials, it is a well-organised, meticulous operation, led by Russians claiming to be archaeological experts, and enacted in the immediate aftermath of the city’s capture. The museum staff, anticipating the danger, attempt to hide the artefacts in a cellar; but their efforts ultimately prove futile; betrayed by a collaborator, they are forced to watch the Russians abscond with the museum’s prized possessions.

Around 2,700 kilometres away in the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam, a similar collection of golden artefacts became embroiled in a legal battle lasting nearly a decade. Loaned to Amsterdam by museums from the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea, the artefacts were left in limbo after Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014. After three high-profile court cases to determine whether the artefacts should be returned to Crimea or Kyiv, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands finally ruled in Ukraine’s favour in 2023. These artefacts and the collection stolen from Melitopol share a common origin: the Scythian civilisation that inhabited the steppes of present-day Ukraine and parts of Russia thousands of years ago. Far from being consigned to the pages of ancient history, the Scythians have now found themselves on the cultural frontlines of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

The Scythians are known today from the substantial surviving archaeological evidence, much of it exquisite golden artefacts from warriors’ tombs, and from historical accounts from the ancient world. A warrior people of Iranian ethnic origin famous for their skills in mounted archery and their nomadic lifestyle, their presence in Ukraine and Russia has left a historical and archaeological legacy to both countries. Some evidence of a more symbolic cultural presence can be found in Russia, where elements of nationalist thought and political philosophy have conceptualised the Scythians as embodying both the warlike side of Russian identity and its sense of cultural superiority over its neighbours. Although ancient history features infrequently in political discourse in both Ukraine and Russia, its relevance lies more in its illustration of the all-encompassing nature of the existential war that Russia has brought to Ukraine. The significance of the Scythians – both in a tangible and symbolic sense – to Russia and Ukraine cannot be considered independently of the wider context of the impact of Russia’s invasion on the cultural heritage of both countries.

Much of our knowledge of the Scythians and their culture comes from the writing of the 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus, considered by many to be the ‘father of history’. He was also the first known historian of Ukraine. In his Histories, a project that aimed to chronicle the extent of the known world and its people, he wrote extensively on Scythian culture, customs and history. The Scythians themselves left no written records and were likely illiterate, so we have to rely on ancient Greek writers like Herodotus to provide an insight into their world.

The term ‘Scythian’ has at times been used as a more general description of the (often interrelated) nomadic steppe peoples of Central Asia, the Caucasus, Russia and Ukraine. Herodotus, however, defines ‘Scythians’ (as I will do here) as the inhabitants of the steppes of what is now Ukraine and a small part of modern-day Russia between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE, having migrated there previously from Central Asia and settled in the land the Greeks called ‘Scythia’. It is unclear whether or not Herodotus ever visited Scythia, although there are several indications in his detailed account of the coastline of southern Ukraine that suggest he travelled at least as far as Greek settlements on the shores of the Black Sea. Greek settlers developed commercial links with the Scythians down the Dnipro River (Herodotus calls it the Borysthenes and compares it with the Nile in Egypt). Some Scythians eventually intermarried with Greek settlers and lived alongside them in multicultural, multilingual trading communities along the Dnipro and the southern coast. This intercultural contact also allowed Scythian legends and tales to make their way into the writings of Greeks like Herodotus.

One such legend made it significantly further than that. Mixoparthenos, a part-woman, part-snake goddess who was worshipped by Scythians on the Crimean peninsula and allegedly considered to be the mythological ancestor of the Scythian race, is the figure that appears in the Starbucks logo. Thousands of years later and thousands of miles across the world, the Scythians’ legacy runs surprisingly deep.

Herodotus’ discussion of the Scythians focuses on a failed invasion of Scythia by the Persian Empire. The Persian king Darius (550-486 BCE) was allegedly motivated by a desire to avenge historical grievances; around a century earlier, the Scythians had invaded and occupied territory in modern-day Iran. In 513 BCE, Darius led a vast force up the western Black Sea coast to establish Persian dominance over Scythia and further expand his colossal empire. Outnumbered and outmatched militarily, the various Scythian tribes united to resist the invasion and resorted to unorthodox tactics. Using their nomadic, mobile lifestyle to their advantage, they avoided open battles with the Persian army and forced the invaders to chase them deep into their territory, towards the Don River. They employed scorched-earth tactics that left Scythia devastated but denied the Persians any tangible victories. Eventually, worn down by fatigue and partisan raids and frustrated by the elusive nature of their foes, the Persians were compelled to abandon their attempt at conquest.

The Scythians’ irreverence is reminiscent of some of the defiant Ukrainian responses to Russia’s invasion

The accuracy of Herodotus’ account is of course subject to debate, as his is the only surviving description of these events. More significant is the narrative he presents of a smaller, militarily inferior force successfully frustrating an invasion against the odds. Here, the parallels with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 seem apparent, although it would be overly simplistic to map one attempt at conquest onto the other, not least because the identities and motives of the invaders differ substantially.

The Persians themselves seem to have told the story rather differently. A royal Persian inscription displayed at Darius’ tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam lists the ‘Scythians across the Sea’ among the peoples conquered by the Persians, and a separate inscription at Mount Behistun mentions Darius’ conquest of Scythia, indicating that – to a domestic Persian audience at least – Darius presented his campaign as a victory. There is no evidence of Persian political or administrative rule over Scythia, other than a string of forts built on the banks of the Don River that, according to Herodotus, were in ruins several decades later.

One anecdote from Herodotus relates that the Scythian king Idanthyrsus had a frog, a mouse, a bird and five arrows delivered to Darius with no further explanation. The Persians initially interpreted this as a pledge of allegiance, akin to the symbolic offerings of earth and water that the Persians demanded from conquered nations. But one of Darius’ advisors eventually gleaned the true meaning: ‘Unless you become birds, Persians, and fly up into the sky, or mice and hide in the earth, or frogs and leap into the lakes, you will be shot by these arrows and never return home.’ Apart from being an example of Herodotus’ characteristic narrative wit, the irreverence and mockery displayed by the Scythians here is reminiscent of some of the defiant Ukrainian responses to Russia’s invasion, from the tiny garrison of Snake Island’s famous retort to the Russian flagship Moskva, to the innumerable memes circulated by Ukrainians on social media to express their defiance and determination to resist the invasion at all costs.

After the failure of Darius’ invasion, the Scythians continued to develop their commercial and cultural relations with Greek settlers in the region and remained in control of Scythia for several centuries until they were eventually displaced by the Sarmatians, another nomadic steppe people from the east. By roughly 200 BCE, Scythian territory had dwindled to the Crimean peninsula, and four centuries later little trace of them remained.

Herodotus’ account of Scythian resistance to the Persians is most relevant in its contribution to a cultural perception of the Scythians’ indomitability, courage and hardiness. This is not to say that his characterisation of the Scythians was overwhelmingly positive. He recounts many of their more brutal alleged customs, such as drinking blood, scalping enemies and performing human sacrifice, to name a few. This characterisation led other Greek authors to depict the Scythians as stereotypical ‘barbarians’: uncouth, uncultured and uncivilised. The Greek term βάρβαρος originated as a general description for any people who did not speak Greek, conveying the meaning ‘foreigner’ or ‘non-Greek’ as well as ‘barbarian’ in the modern sense of the term. However, it gradually came to be associated with the hostile caricatures with which Greek (and especially Athenian) literature portrayed foreigners.

Evidence from Greek literature and vase paintings indicates the presence of a group of Scythians as some sort of police force in Athens during Herodotus’ lifetime. The circumstances surrounding the establishment and responsibilities of this force remain unclear, but it is likely that encountering Scythians in their daily lives would have helped Greeks to associate them with the image of the ‘barbarian’. A member of this alleged police force appears as a ‘Scythian archer’ in a play by the comic playwright Aristophanes, speaking broken Greek and intended as an object of mockery – a far cry from the Scythians of Herodotus’ Histories.

The depiction of the Scythians by ancient writers, from their customs and practices to historical events such as Darius’ invasion of Scythia, may not be entirely accurate. But this matters less than the lasting cultural perception of the Scythians as a warlike, savage but also indomitable and powerful people, rulers of the steppes in the far north of the known world. This undoubtedly influenced later cultural conceptualisations of the Scythians in the lands they once inhabited, particularly in Russia where nationalist thought has incorporated the image of the Scythian into a wider conception of Russian identity.

This symbolic appeal of the Scythians to nationalist ideology in Russia began in the 19th century and still exists to a certain extent. The discovery and excavations of Scythian burial mounds (known as kurgans or kurhany) from the 18th century onwards accrued more widespread public interest in the Scythians. Dotting the steppes of Ukraine and Russia, many kurhany were found to contain valuable Scythian artefacts worked in gold and silver. Ukraine’s most prized Scythian artefact is an elaborate golden pectoral from the Tovsta Mohyla kurhan, discovered in 1971 near the city of Pokrov. Made from solid gold, it depicts intricately worked scenes of humans and animals (both real and mythological).

The golden pectoral from the Tovsta Mohyla burial mound. Courtesy the Museum of Historical Treasures, Kyiv/Wikipedia

Other finds in the kurhany provided evidence of the Scythians’ extensive trade links with regions as far away as China, from where some of the artefacts originated. Excavations of Greek settlements in the late 19th century also unearthed Scythian relics such as a limestone statue of Mixoparthenos, the snake goddess who appears in the Starbucks logo, in the Greek settlement of Pantikapaion (modern-day Kerch). Although many of the kurhany were physically located in Ukraine, no distinction of ownership was made between finds from excavations in Ukraine and those in Russia and elsewhere until Ukraine became an independent state in 1991.

,_a_hybrid_creature_from_the_Black_Sea,_limestone_sculpture,_1st-2nd_century_AD,_from_Panticapaeum,_Taurica_(Crimea)_(12852697335).jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Limestone statue of Mixoparthenos, 1st to 2nd Century CE. From Panticapaeum, Taurica. Courtesy Wikipedia

Inspired by the archaeological discoveries, a literary and cultural movement known as Skifstvo (‘Scythianism’) emerged in late 19th-century Russia that identified ideologically with the Scythians as Russia’s cultural forebears. These poets and artists viewed the Scythians through the lens of Russia embracing its identity as both Asiatic and European, as well as freeing itself from the (European-imposed) constraints of moderation and etiquette. They were idealised in art and poetry as wild, untamed and fierce warriors living in harmony with the natural world. In the words of the historian Orlando Figes, the Scythians became ‘a symbol of the wild rebellious nature of primeval Russian man’. One of Pushkin’s poems contains the lines ‘Now temperance is not appropriate/I want to drink like a savage Scythian’. Association of the Scythians with drunkenness has been a literary trope since ancient Greek times.

Members of a notorious far-Right biker gang involved in the invasion of Crimea use the pseudonym ‘Scythian’

Perhaps the most famous example of Skifstvo is the poem Skify (1918) (‘The Scythians’) by Aleksandr Blok, in which the poet emphatically identifies Russia with the Scythians, as a means of asserting its cultural superiority over West and East alike. The poem depicts Russians as Scythians keeping ‘two hostile powers –/Old Europe and the barbarous Mongol horde’ at bay, using the image of the Scythian to present Russia as superior to both in terms of population size, military strength and national character.

The Scythians have since been appropriated as a symbol of cultural superiority by present-day Russian nationalists, but any remaining links with the Skifstvo of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are tangential and distorted. One fringe group calls itself the ‘New Scythians’ and members of a notorious far-Right biker gang involved in the invasion of Crimea have used the pseudonym ‘Scythian’ when interviewed by international media. These groups subscribe to the wider ideology of ‘Eurasianism’, a far-Right, ultranationalist movement that seeks to restore Russian dominance over its neighbours in ‘Eurasia’, especially Ukraine. Eurasianism is at its core deeply hostile to the West and supportive of a Russia-dominated sphere of influence that corresponds to the former borders of the Soviet Union. Its proponents, most notably the far-Right philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, have spent decades advocating against Ukrainian independence and in favour of Russian political control over its neighbour. The image of the Scythian is an admittedly minor element of this strain of nationalist ideology.

Scythians have, however, made a recent cinematic appearance in a big-budget Russian historical-fantasy epic released in 2018. Skif (‘The Scythian’) imagines the ahistorical existence of a group of Scythians in the medieval state of Kyivan Rus, the last remnants of an ancient civilisation who have somehow survived centuries after their historical presence in these lands. Despite this historical inaccuracy and the film’s brutal, almost comically overblown action scenes (featuring a man who can partially transform into a bear), the film’s depiction of the Scythians themselves is fascinating. Rustam Mosafir, the film’s director, was evidently familiar with Herodotus’ tales of the Scythians, presenting them as savage, nomadic raiders who set the plot in motion by abducting the wife and child of the protagonist Lyutobor, a Kyivan Rus warrior. To save them, Lyutobor is forced to make an uneasy alliance with a Scythian outcast; over the course of the film, this develops into a sense of mutual respect despite the cultural gulf between them.

Skif contrasts the brutal but honour-bound Scythians with the duplicity, conspiracy and power struggles of the film’s Kyivan Rus. This is exemplified by the character of Oleg, based on a real-life Rus prince. At the film’s conclusion, Oleg massacres the entire Scythian tribe after promising them his protection, asserting that he will have absolute dominance over his land and that no people other than his will inhabit it. Lyutobor subsequently refuses to recognise Oleg’s authority and declares himself to be a Scythian instead, thereby rejecting his Kyivan Rus identity and self-identifying as the last of the Scythians.

Given the prominence of Kyivan Rus in Russian nationalist thought and pseudohistorical narratives that identify Kyivan Rus with the modern Russian imperialist project, it is striking that Skif invites its Russian audience to identify instead with the seemingly culturally alien, barbaric Scythians. The cynical perspective on power and authority articulated by Oleg is particularly interesting considering the fact that Skif was filmed in Crimea in the years following Russia’s annexation of the peninsula. Whether or not Mosafir intended Skif to be subversive, it would be difficult to interpret its depiction of the Scythians as inspired by Russian nationalism.

Russia’s current invasion of Ukraine has brought the Scythians to the world’s notice most notably with the lengthy legal dispute over the Scythian artefacts in the Netherlands. Over ten years ago, shortly before Russia’s invasion of Crimea, an exhibition of Scythian artefacts was displayed at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam. Entitled ‘Crimea: Golden Island in the Black Sea’, it displayed 565 artefacts from Crimean museums, including golden ceremonial helmets and weapons and ornate jewellery intricately worked by skilled Scythian craftsmen. Most were made from gold, but not all (such as the limestone statue of Mixoparthenos from Pantikapaion). Their estimated combined value was almost €1.5 million. By the time the exhibition concluded, Crimea had been occupied by Russia and a dispute arose about whether the Crimean artefacts should be returned to their original museums or to Kyiv. Naturally, the Crimean museums requested the return of their artefacts. Ukraine claimed the collection was its legal property and that returning the artefacts to occupied territory would in effect be relinquishing them to Russia.

This dispute resulted in a nine-year legal marathon in the Dutch courts, eventually reaching the Supreme Court. All three of the court rulings – by a lower court in 2016, the Court of Appeal in 2021, and the Supreme Court in 2023 – were in Ukraine’s favour. The Crimean museums appealed the result of each case, but their efforts were in vain. In June 2023, the Supreme Court rejected their final appeal, upholding the decision of the lower courts. In November, the artefacts were finally returned to Kyiv, where they currently reside. Russian media and politicians denounced the Dutch courts as biased and politicised, and claimed that they were the true victims of theft and issued a slew of vague threats.

This is part of Russia’s attempt to appropriate, subsume and erase Ukrainian cultural identity

Litigation has been far from the only consequence of Russian claims to Scythian artefacts from Ukraine, as demonstrated by the theft of Melitopol’s Scythian collection. The Museum of Local Lore in the southern city of Kherson faced a similar fate. When Ukrainian troops retook the city in November 2022, they found the museum stripped bare of Scythian and other artefacts by the Russians. Unlike Kherson, Melitopol remains under Russian occupation, but its golden Scythian artefacts are presumably now ensconced within museums in Russia itself. These acts indicate a motive deeper than simply greed. Russia is attempting to deny Ukraine its cultural heritage and claim it for its own.

Scenes from the looted Kherson Regional Museum of Local Lore

Yet despite this, the Scythians are still rarely, if ever, mentioned in contemporary Russian discourse. This is particularly unusual given the current tendency of Russian politicians and media to weaponise history in order to assert Russian greatness and justify its imperialist ambitions in Ukraine and elsewhere. In a recent interview with the American Right-wing media personality Tucker Carlson, Vladimir Putin declaimed a lengthy list of historical grievances, many dating to the medieval times, in order to justify his invasion of Ukraine. The Scythians received no mention; indeed, it is striking, given the frequency of the use of historical narratives in today’s Russian political and media environment, that they feature only in fringe far-Right political theory. Even the discussion of the dispute over the Scythian artefacts from Crimea reveals more about Russian efforts to assert control over Crimea and its cultural heritage than it does about attitudes to the Scythians themselves.

Russia’s designs on Ukraine’s Scythian artefacts are merely a single aspect of its broader attempt to appropriate, subsume and erase Ukrainian cultural identity. This has become a central objective of Russia’s war. Putin’s denial of Ukraine’s right to exist and the independence of Ukrainian culture from Russia predates (and indeed, was used to justify) the full-scale invasion of 2022. Similar views have been shared by a wide range of prominent Russian politicians, journalists and other public figures, many of whom have also called for the destruction of Ukraine and its people, and publicly shared genocidal opinions.

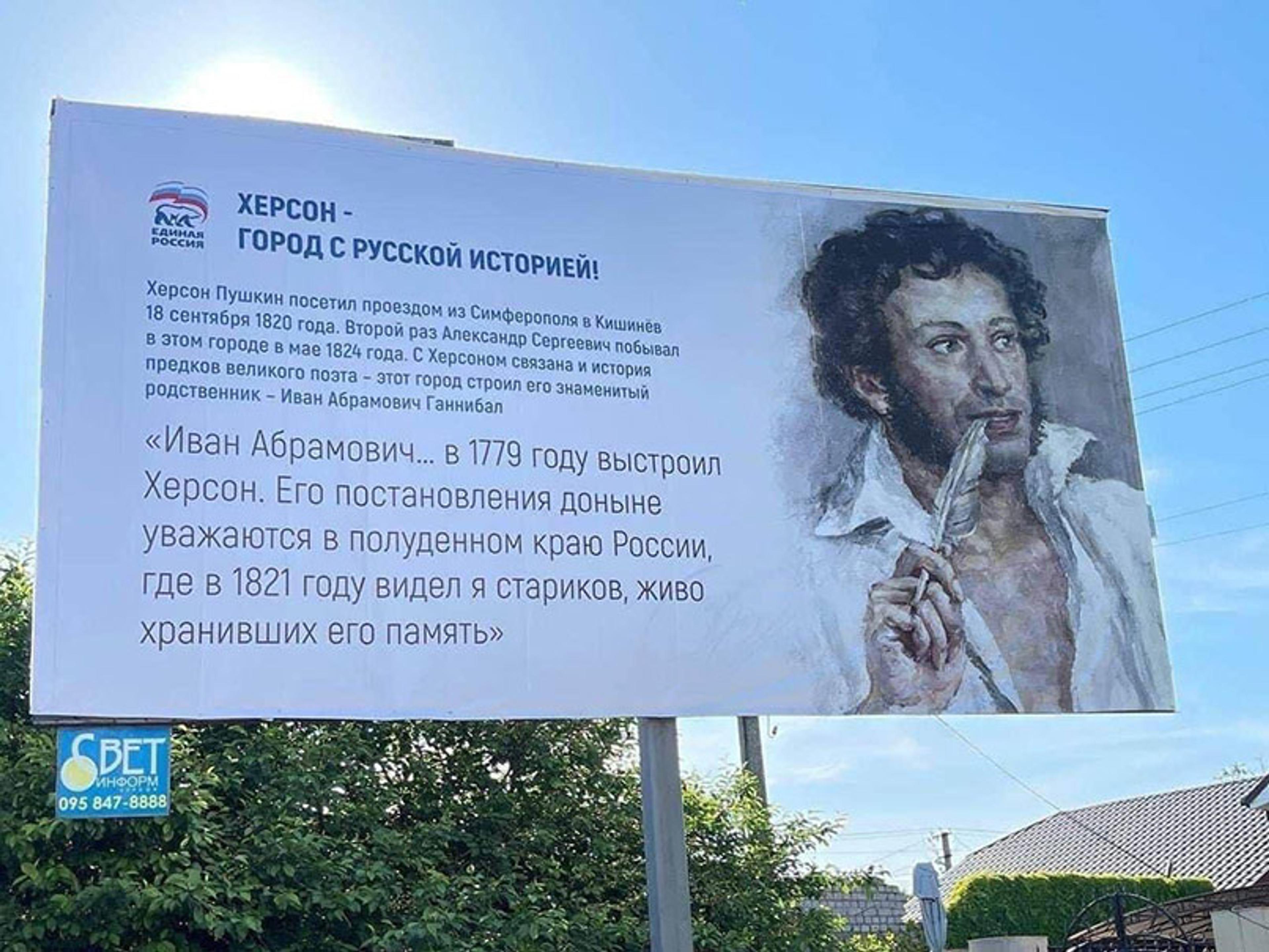

Russia’s full-scale invasion attempted to transform this rhetoric into reality. The invading forces have deliberately targeted and destroyed hundreds of Ukrainian sites of cultural heritage. Looting has been widespread, forcing museum curators across the country to take specific measures to safeguard their collections, including Scythian artefacts. In the regions it has occupied, Russia has erected posters and billboards portraying Russian cultural and literary figures, some deliberately positioned atop the ruins of Ukrainian cultural heritage sites destroyed by its bombing. In Mariupol, occupying Russian forces constructed a crude façade depicting Russian literary and cultural figures around the ruins of the city’s famous theatre, destroyed by Russian shelling that killed up to 600 Ukrainians. The looting of artefacts from cities such as Kherson and Melitopol signifies not that the Scythians are intrinsically culturally important to Russia, but that they represent the tangible cultural history of a country that Russia claims as its own. In an existential effort to assert Russian dominance over Ukrainian culture in its entirety, ancient history has not been spared.

Soon after the invasion, posters began appearing of Russian cultural icons; in this case, the poet Pushkin. Photo courtesy Karyna Struk/X

This attempt, like Russia’s invasion, will not succeed. The Scythians are part of the history of both nations. Despite its efforts, Russia has not been and will not be able to deny Ukraine its historical and cultural identity. As for the artefacts themselves, the Scythian gold collection at the centre of the Dutch legal dispute is now back in Kyiv, but this is not its final destination. Volodymyr Zelenskyy has stated that when the Ukrainian flag flies in Crimea once more, the Scythian artefacts will return along with it. The eventual return of those stolen from Melitopol seems far less likely at present. But however long it takes, these artefacts have already survived for thousands of years. They will endure.