Sometime around 650 CE, Mahdukh, daughter of Newandukh, had a headache. I first read about Mahdukh’s migraines – excruciating and debilitating – on the inside of a bowl. Her name is written in black ink among spiralling, partially faded lines of Jewish Aramaic, the language of late antique Mesopotamia’s Jews, on an unglazed clay vessel’s inside surface.

Just beneath the lip of the bowl, a black circle surrounds the 15 lines of text. ‘By your name, I act, great holy one,’ the scribe, who was also the magical practitioner, begins in the first person. ‘May there be healing from heaven for Mahdukh daughter of Newandukh.’ The incantation calls powerful intercessors to her aid: divine names, magical words, angels and spirits and biblical verses.

Surprising though it might seem, Mahdukh’s headaches have changed how scholars understand a crucial period in Jewish history. At the same time, her migraines have become entangled in debates over ethics, ownership and our responsibility to the past.

Thousands of similar incantation bowls, also known as magic bowls, were produced in the area of today’s Iraq between the fifth and eighth centuries. Like Mahdukh – who commissioned dozens of bowls – clients used incantation bowls to protect and heal, to frighten off demons and evil spirits, and, in a few cases, to enlist demons to help secure love or money, or to harm adversaries.

In addition to the magical texts, scribes sketched drawings of bound and chained demons – pictorial representations of the spells’ desired effect – on the bottom of about a quarter of the bowls.

Late-antique Mesopotamia was religiously and linguistically diverse. Most of the population, including Christians, Manichaeans and those who still followed the ancient Babylonian religion, used a dialect of Aramaic known as Syriac. The Mandaeans, a small, Gnostic religious community whose members have now mostly fled Iraq, had their own, closely related Aramaic dialect. So did the Jews, a longstanding minority whose presence, the Bible tells us, goes back to the Judean exiles first deported to Babylonia by Nebuchadnezzar in the 6th century BCE. The region, an important province of the Iranian Sasanian empire, whose capital was located near present-day Baghdad, was also home to Persian-speaking Zoroastrians.

The bowls reflect this diversity, though not in the way we might expect. The largest number of known incantation bowls are written not in Syriac, but in Jewish Aramaic by Jewish scribes (though not necessarily for Jewish clients). Mandaean bowls are the second most numerous, only then followed by bowls in Syriac. A handful of bowls in Arabic and Persian are also known, in addition to bowls – perhaps 10 per cent – that can only be called ancient forgeries. These latter are filled with scribbles that mimic cursive writing but are not, in fact, in any language at all; perhaps they were made by illiterate scribes preying on equally illiterate clients.

The prevalence of Jewish Aramaic bowls are what makes these artefacts so important for Jewish history. They provide the sole piece of epigraphic evidence documenting Jewish language and religion at one of the most important times in Jewish history: the period of the composition of the Babylonian Talmud.

The Babylonian Talmud is a massive collection of law, commentary, exegesis, legend and myth. Passed down and expanded orally by generations of rabbis, the Talmud, committed to writing only in the early Middle Ages, became the ultimate arbiter of Jewish life and practice for communities from Spain to India. Today, almost without exception, Judaism is Talmudic Judaism. Even Jews who reject Judaism are in effect rejecting a religion cast in the Talmud’s mould.

The Talmud itself contains a number of stories about demonic encounters and rabbis using magic to heal and harm (though it never refers to incantation bowls specifically). Scholars once dismissed these passages as anomalies meant to placate the rabbis’ unsophisticated flock. But the incantation bowls unequivocally show that there was much rabbinic culture shared with such magical traditions. Demons mentioned in the Talmud, such as Ashmedai and Lilith, also appear in the bowls, as do stories about rabbinic sages and wonderworkers. Mahdukh’s bowl contains just such a story, similar, though not identical, to others found in the Talmud, about the Jewish sage Hanina ben Dosa vanquishing a demon by reciting a biblical verse. Rabbis are even named in a few cases as the bowls’ clients.

However, the incantation bowls do not simply confirm the picture of Babylonian Jewish life that the Talmud presents. The Talmud, like other late-antique theological works, is concerned with protecting the boundaries of the faith from outside influence. Magicians adhered to a different standard.

Though written by Jewish scribes, many of the clients of the Jewish Aramaic bowls were not themselves Jews. Mahdukh, daughter of Newandukh, for instance, has a typically Zoroastrian name: Mahdukh means ‘daughter of the Moon’, a Zoroastrian deity, and Newandukh is Persian for ‘daughter of the brave’. Other bowls were made for clients with similar names, including Ispendarmed, the Zoroastrian goddess of the Earth; Burznai, meaning ‘high’ or ‘elevated’; and Gushnasp, the name of a sacred Zoroastrian fire.

But the interest in foreign magic went in more than one direction; Jews, including rabbis, purchased bowls from non-Jewish scribes. ‘Everyone goes to everyone,’ said Gideon Bohak, an expert on ancient religion at Tel Aviv University. ‘You visit healers and magicians who are from different religious and social traditions. It’s something that happens all the time, partially because the neighbour’s grass is always greener; the neighbour’s magic is always more powerful.’

Magicians of all stripes also incorporated foreign influences in their work. Though written in different dialects, the Jewish, Mandaean and Syriac incantation texts often share extended passages and use the same spells. One striking example is found on an otherwise unexceptional Jewish Aramaic bowl that invokes, among other protective spirits, ‘Jesus, who conquered the height and the depth with his Cross, and in the name of the Exalted Father, and in the name of the Holy Spirits, forever and ever, Amen Amen Selah.’ Bohak noted that the client might have been a Christian for whom the Jewish scribe included a special paean to the Trinity.

This openness to influence, said Siam Bhayro, professor of theology at the University of Exeter, was probably a function of the market. ‘If Christian practitioners have the latest fad, of course Jewish practitioners or pagan practitioners are going to want it as well, to make themselves more marketable. You can see this being driven by economic imperatives.’

We don’t know where or when Mahdukh’s bowl was discovered. This recent history, while fragmentary and contentious, is as much a part of the artefact’s story as the rabbis and magicians of late antiquity. For incantation bowls are, of course, not just texts. They are artefacts of considerable interest – and value – to collectors and dealers in the global antiquities trade.

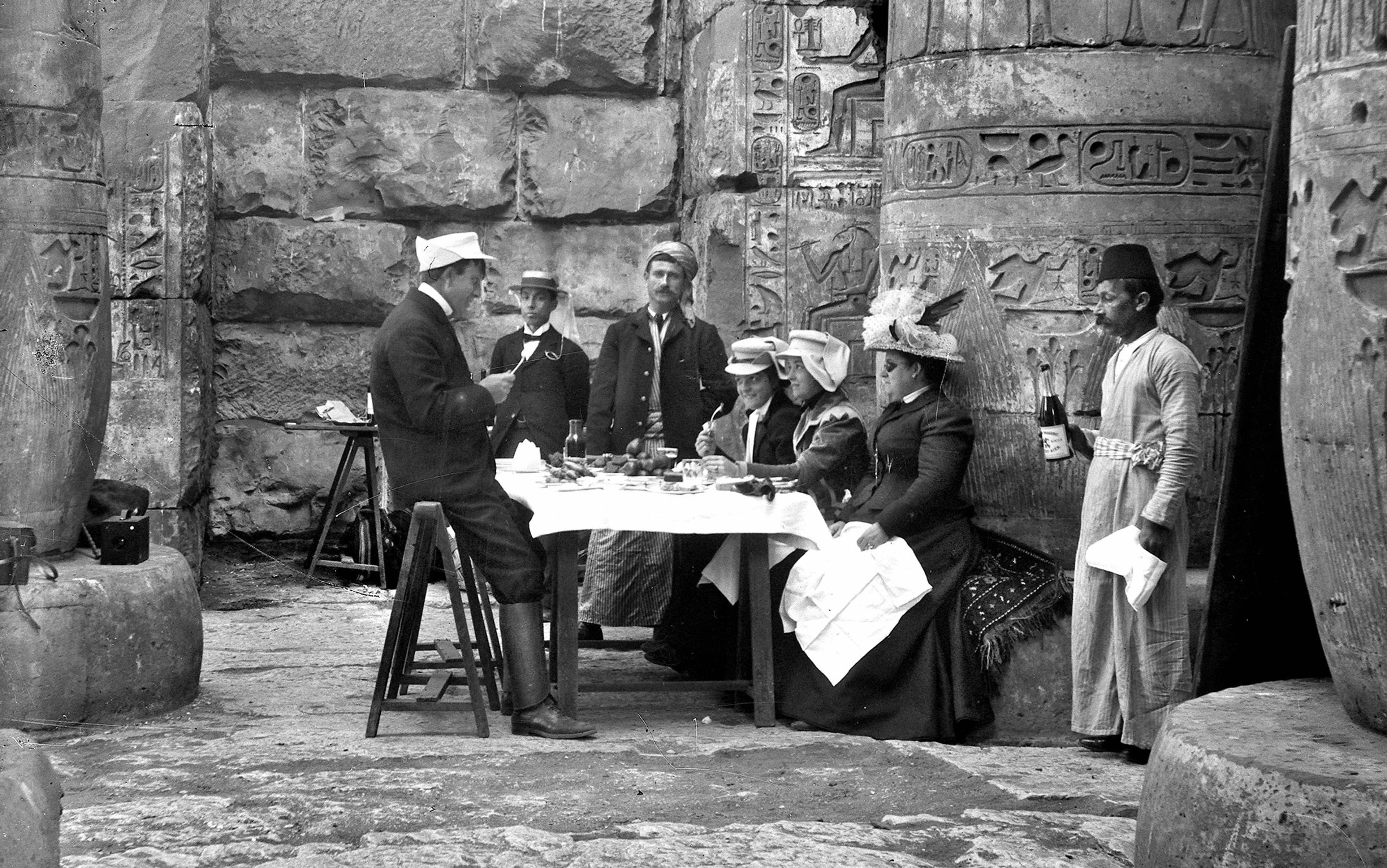

Nearly every museum in the world contains such unprovenanced antiquities. This abundance can partially be explained by the fact that scientific archaeology, with its emphasis on artefacts’ context, is so new. Current archaeological methods began to be widely employed in Iraq only in the 1920s, and museums are full of Assyrian statues, Babylonian tablets and Sasanian seals amassed by earlier collectors. The first published reference to the incantation bowls, Austen Henry Layard’s Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (1853), reads more like an Orientalist adventure than an academic tome. The description and translation of the bowls he discovered is sandwiched between accounts of a precocious 12-year-old Arab sheikh and the Ottoman governor’s tame lion.

‘The tragedy is that these bowls would have contributed so much to knowledge if their context had been known’

But is also because of looting. The practice of swiping valuables from tombs and ancient sites is nothing new, but in recent decades the looting and smuggling of antiquities has grown into a major problem worldwide. Advances in technology, communications and transportation have made it possible for objects from illicit excavations to reach dealers and collectors abroad within days. This is especially true in antiquities-rich but governance-poor places such as Iraq, where the authorities that could protect sites and prosecute smugglers are weak or nonexistent. Iraqi antiquities began entering the market on a massive scale in 1991, in the political chaos and economic collapse that followed the first Gulf War and, as the 2003 looting of the National Museum of Iraq demonstrated, the looting only increased after the US-led invasion that year.

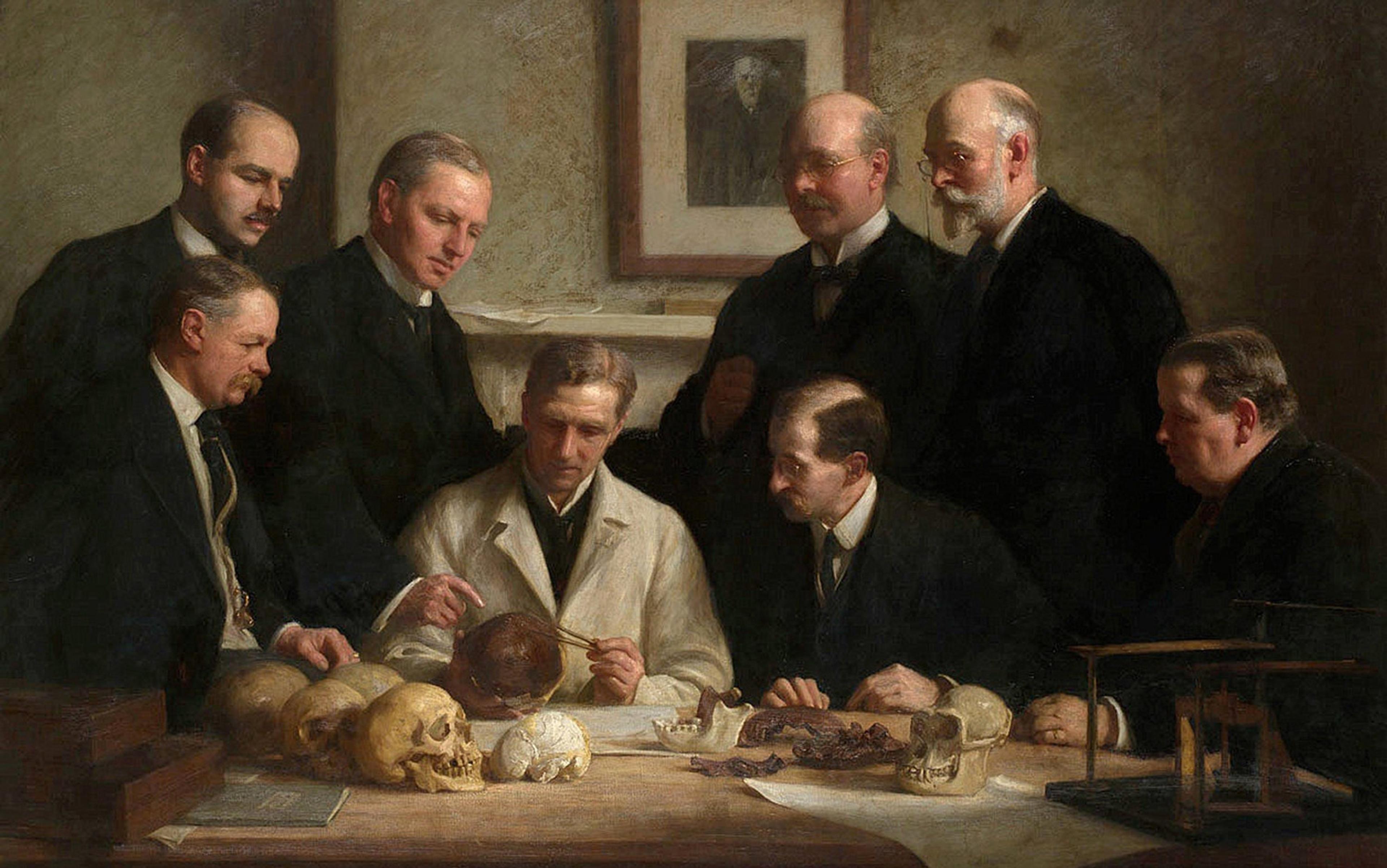

For archaeologists, unprovenanced antiquities have little to tell us. ‘It’s not just the objects that are interesting, it’s the detailed circumstances of the discovery,’ explained Colin Renfrew, now senior fellow of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge. ‘The tragedy is that all these incantation bowls would have contributed so much to knowledge and understanding if [the details of] their context and discovery had been known.’

However, Renfrew and others say that not only are these bowls not worth studying, but that they shouldn’t be studied. They argue that the study of these incantations, innocent as it might seem, is the last link in a chain of lawbreaking that begins with looting, theft and cultural destruction.

Mahdukh’s bowl, catalogued as MS 1927/45, is now owned by the Norwegian collector Martin Schøyen. He has amassed the world’s largest private collection of manuscripts, from cuneiform tablets to Scandinavian seals and Mayan vases. His collection includes 654 incantation bowls, the most in private hands.

In 1996, Schøyen invited Shaul Shaked, professor emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a leading expert in the field, to work on the incantation bowls. For Shaked’s convenience, the Norwegian collector arranged with University College London’s department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies for the bowls to be kept at a university warehouse. For nearly a decade, Shaked worked on the bowls and published the fruits of his research.

Meanwhile, Norwegian journalists and academics were becoming suspicious about the origins of Schøyen’s collection. In September 2004, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation aired the documentary The Manuscript Collector. It alleged that Schøyen’s incantation bowls had been looted from Iraq in 1992 in violation of international sanctions and British law. In the wake of the documentary, in October that year, UCL officials announced that they had contacted London’s Metropolitan Police, who informed them that they saw ‘no reason to take the matter further’ and that there was ‘no objection to the return of the material to Schøyen’.

However, acknowledging a UNESCO treaty banning the sale of antiquities whose ownership history before 1970 could not be demonstrated (a treaty that the UK had ratified in 2002), UCL appointed an independent inquiry tasked with establishing the provenance of the bowls. The committee was made up of London lawyer David Freeman; Sally MacDonald, then director of UCL Museums and Collections; and Renfrew. It delivered its report in July 2006. Though suppressed as part of the settlement of Schøyen’s 2007 lawsuit against UCL for return of the bowls, Renfrew deposited a copy in the House of Lords Library in 2009, and it became available on WikiLeaks that same year.

According to the report, Schøyen began buying incantation bowls from various London antiquities dealers in the early 1990s. All these dealers, in turn, had bought their bowls from a Jordanian named Ghassan Rihani.

Rihani, who died in 2001, was well-known in the antiquities community. He’d been head of the Jordanian Antiquities Association, and in 2003 The New York Times described him as a middleman dealing in looted Iraqi antiquities. A knowledgeable Jerusalem dealer also told me that Rihani was perhaps the main conduit in bringing stolen Iraqi artefacts to market.

For his part, Schøyen told the inquiry that the bowls came, not from Iraq, but from Rihani’s family collection, in existence since 1965, with origins going back to 1935. The report discusses at length two Jordanian documents presented as evidence of Schøyen’s claim. These documents are so vague that they could refer to any number of antiquities, or almost anything at all. Alone, they do fall far short of establishing a provenance for the bowls, though a London dealer told me that other documents, not mentioned in the report, paint a more complicated picture.

Nonetheless, the UCL report concluded that ‘on the balance of probabilities’ the bowls were removed from Iraq after 1990, in violation of Iraqi law and international sanctions. It cites Iraq’s first antiquities law, from 1924, granting the Iraqi state primary ownership over all antiquities and prohibiting unauthorised export, and recommends that UCL return the 654 incantation bowls to the department of antiquities of the state of Iraq.

The report also calls on UCL to follow ‘not merely the dictates of legal doctrine, but the demands of ethical principle and public decency’. But, in fact, what do ethics and decency demand? While Renfrew and others are adamant that the incantation bowls should be returned to Iraq, other scholars argue that Jewish Aramaic bowls are part of Jewish history, not of the modern Iraqi state. Considering Iraq’s treatment of its own Jewish citizens, they say, returning the bowls would be foolhardy and unjust.

If the bowls were in Iraq, many of the leading scholars in the field, including Shaked in Jerusalem, would no longer have access to them. Jewish scholars, Israeli or otherwise, have never been given permission to study the National Museum of Iraq’s 600 incantation bowls, the largest publicly owned collection in the world. Under Saddam, Jewish archaeologists were specifically excluded from working in Iraq. The attitude among some Iraqi archaeologists, it seems, remains unchanged. In September, Ali al-Nashmi, professor of history at Al-Mustansiriya University in Baghdad, said that an international Jewish conspiracy ‘reinforced following the 1897 Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland’ was plotting to steal the Middle East’s antiquities and destroy its Arab heritage. ‘That,’ he said in an interview with Al Mayadeen TV network, ‘is why the most prominent archaeologists in the world are Jews.’

‘A British person doesn’t feel it very much,’ Shaked said. ‘But Jews aren’t allowed to enter certain parts of the world. And sometimes the things are connected to them personally – to their history and their tradition.’ The bowls, he continued ‘can be anywhere, as long as they allow access to the material’.

Neil Brodie, one of the foremost researchers on the illicit antiquities trade, was sympathetic to this point. ‘We recognise the realities of the situation on the ground at the moment,’ he said. ‘We realise that this body of material is unusual: it’s Jewish, not cuneiform tablets. There are questions hanging over its fate if it is returned to Iraq.’

Brodie also argued that the situation is not as stark as Shaked implied. Returning the bowls to Iraqi ownership, he said, does not necessarily mean returning them to Iraqi territory. They could be housed in an institution outside the country until the political situation improves – the British Museum, the Louvre and other institutions have offered to serve as safe havens for material from war zones – and until all researchers are granted access to them. ‘People could accuse me of being a bit idealistic and naive,’ he added, ‘but it’s actually a very pragmatic approach.’

Brodie cautioned, however, that there are even more serious ethical issues. When scholars publish unprovenanced antiquities, or museums exhibit them, the market value of the objects increases – 10 times, he has written, in the case of the incantation bowls. There is a common-sense logic to this: Mahdukh’s bowl, which has been translated, published and deemed important to Jewish history, will command a higher price than a bowl no one has read about and that might well be covered with meaningless scribbles. As the value of these objects rises, so does the demand for more, similar antiquities. The increase in demand is met with an increased supply: more looting on the ground.

I asked Brodie how this could apply to the particular bowls owned by Schøyen, which – assuming they were looted – were removed from Iraq so long ago.

‘There might be an equivalent site or a better site and we don’t want the same thing to happen to that,’ he answered. ‘If we keep falling back and saying: “Well, that’s already happened so we might as well carry on with business as usual,” in 10 or 20 years we might be dealing with another similar or worse situation. So to stop it happening in the future we have to deter people from buying this material now.’

‘If you destroy the market entirely, then someone will come and just blow up all the bowls’

But the London dealer I spoke with said that, in the particular case of the incantation bowls, scholarly activity did not cause more looting. ‘That’s not an unrealistic thought, but it’s not reality,’ he said. ‘There was no secondary market for them. There wasn’t a third collector or a fourth collector. There was only these two collectors’ – referring to Schøyen and the recently deceased Shlomo Moussaieff. ‘By the time that both of them had stopped buying, there were enough problems with magic bowls that nobody would buy them anyway.’

As stricter guidelines make it harder to buy and sell unprovenanced antiquities in London – once a centre of the trade – the market is moving east. Singapore has become a transit point for looted artefacts from Iraq and elsewhere, and others mentioned collectors in the Gulf, China and Japan. In Brodie’s eyes, this is a success. ‘In the end, there will be nowhere to run and nowhere to hide,’ he said. As the market for antiquities moves, attention and pressure has to shift to those new environments.

In the meantime, though, until trading unprovenanced antiquities becomes inviable everywhere, scholars say that important discoveries will simply disappear, and that the looting continues on the ground regardless of how strictly ethical policies are enforced in the UK. ‘The crimes are happening in any case,’ said Bohak. ‘It’s happening whether you like it or not and whether you’re collaborating or not. Then the question is: are your steps helping at all, or is it only a way of clearing one’s conscience: the crimes are happening but not with British pounds so we don’t care.

‘In some cases, it seems that they’ve caused more damage than not,’ he continued. If recognised institutions are unable to purchase unprovenanced antiquities, it means that they will be traded only among private collectors. Access to material in private hands depends on the owner’s good will, and that of his or her heirs. ‘And if you destroy the market entirely, then someone will come and just blow up all the bowls.’

For Brodie, though he did not describe it as dramatically, the sacrifice of a certain number of antiquities would be a small price to pay in exchange for many more remaining underground, unexcavated and not looted. ‘Imagine if strong action had been taken in 1990, how much heritage would have been saved,’ he wrote to me after we spoke. ‘It would include, perhaps, a unique incantation bowl site.’

Shaked, for his part, is adamant that he will continue studying and publishing the bowls. ‘As a researcher, I won’t allow anything that has historical meaning and importance to rot someplace and not touch it, or be destroyed because someone can’t sell it,’ he said. ‘I think that it is a crime against humanity to allow this material to be lost.’