My 13-year-old nephew Butta was getting into trouble weekly. Arguing with teachers, ignoring administrators, and walking out of class. To the point where my sister had a time-block in her schedule every month dedicated to parent-teacher conferences – but they didn’t work.

Butta is as harmless as he is plump – that jolly kid who loves to split up his chips between his friends and would gladly give you the last bite of his sandwich. He’s never been in trouble outside of school, which says a lot, since his dad, the rest of his uncles and I had all been arrested or kicked out of a school at least once by the time we reached his age.

‘What’s going on with your classes?’ I asked him.

‘My teachers hate me and they throw me in wit Mr Ronald, that sub who be on his phone all day, talkin’ about he don’t need this job, cuz he got his own company! He ain’t got no company!’

Butta’s in middle school so he should have more than one teacher. But they throw all the troubled kids in one class with a long-term substitute teacher all day, where they are allowed to shoot dice, play cards, IG, Tweet, Facebook, dance, stand on desks and basically do whatever they please. I’ve been guilty of pushing subs around – everybody taunts the sub when the normal teacher is absent, but these kids have been doing this for months.

Everyone knows how tough the middle schools in Baltimore are. I recently had a conversation with Stacey Cook, a former teacher from James McHenry Elementary/Middle in South Baltimore and she told me that they had multiple shootings last year, right in front of their building during school hours. ‘One day the gym teacher was almost caught in the crossfire. He hit the buzzer, fearing for his life, begging to be let in. But the principal waited until the shooting stopped. He said we knew where we were and that’s how it is. The gym teacher, me and a bunch of other educators left at the end of the year.’

I’m grateful that no one has shot up my nephew’s school, but his learning experience was still criminal. Being trapped in a room for six-plus hours a day, surrounded by chaos and a sub fingering his phone sounds illegal.

I thought that Butta and his teachers probably had a communication problem that I could mediate. A lot of inner-city teachers are used to dealing with just one parent, if any – I wanted to be the objective voice considering all points of view with the hope of helping him develop a working relationship with his teacher and getting back on track, so I decided to visit.

My sister and I pulled up in front of his school on a Monday. It looked clean from the outside and was located on a nice tree-lined block.

We were buzzed into a narrow hallway. Three huge school officers in small uniforms clogged the path. They looked like COs. The built-in metal detector was cracked and unplugged, so in prison fashion one of the guards scanned us with a wand while another checked our credentials. We passed their test and were directed to the main office, a level up at the end of the same hallway.

The stairwell smelled like used rubbers and rat piss. Blunt guts, unidentifiable fluids and candy wrappers laced the floor. I stepped over all of that and made my way to the office. Some concerned-looking parents and guardians were present, probably trying to see what it would take to make sure their kids received a quality education – the same thing I wanted to do for Butta.

I got the concept of dreaming; but my ancestors came here bearing only fear, chains and uncertainty

We greeted the secretary. She seemed nice, remembered my sister and instructed us to sign in before sending us up to Butta’s class. That same funky smell in the stairwell greeted us again as we advanced another level.

This school seemed like a jail, and level two – Butta’s floor – was the psych ward. Students bolting up and down the hallways, desks taking flight, a trail of graded and ungraded papers scattered everywhere, fight videos being recorded on cellphones, Rich Homie Quan turned to the highest level, crap games and card games going down with children named Bitch and Fuckyou everywhere – all bottled up and sealed with that same shitty smell, so bad it was loud enough to hear, a shit stench I hoped wouldn’t stick to my flannel.

‘So this is it,’ my sister says with an uneasy smirk. This is her only option. She’s raising Butta alone and even though we all chip in, private school is still too expensive. Butta’s classroom was an East Baltimore block party – slam-dancing, students leaping from tabletop to tabletop, and one of the substitutes Butta talked about texting and Facebooking. A main goal for our visit was to get Butta away from the texting sub and back to his real teacher, but she was gone that day anyway – stomped down and beat up, we later learned, by eighth-grade girls mad after she confiscated their cell phones.

It’s hard to receive a good education in this environment. I’d be hard pressed to believe a good teacher could be effective. The computers were ancient, the textbooks were decayed, and the classroom felt like it was 15 degrees Fahrenheit – 30 to 35 musky, puberty-drenched kids and it was still cold. How can you learn in the cold? How can we be in the United States, in 2014, in a major metropolitan city and not have temperature-controlled rooms? I mean, the main office was nice and cozy so why were the classrooms meat freezers?

Not that I was surprised. My middle-school experience had been identical, from the smell and lack of technology to the over-worked and/or disengaged teachers who turned into a sub-hub by mid-year. Add that learning experience to the idea of being educated in a war zone. My story in conjunction with Butta’s does nothing but follow a long tradition of the African-American educational experience in the US.

Back in the late 1990s, my all-American, apple-pie-faced middle school history teacher used to put us to sleep with his month-long patriotic rants. He would gaze into the sky and tell stories about how the US was the only place where you could come bearing nothing but your religion and a dream, and experience an inexhaustible amount of success. I got the concept of dreaming; but my ancestors came here bearing only fear, chains and uncertainty. They were not people in search of hope but captives forced to cultivate and construct the so-called free world.

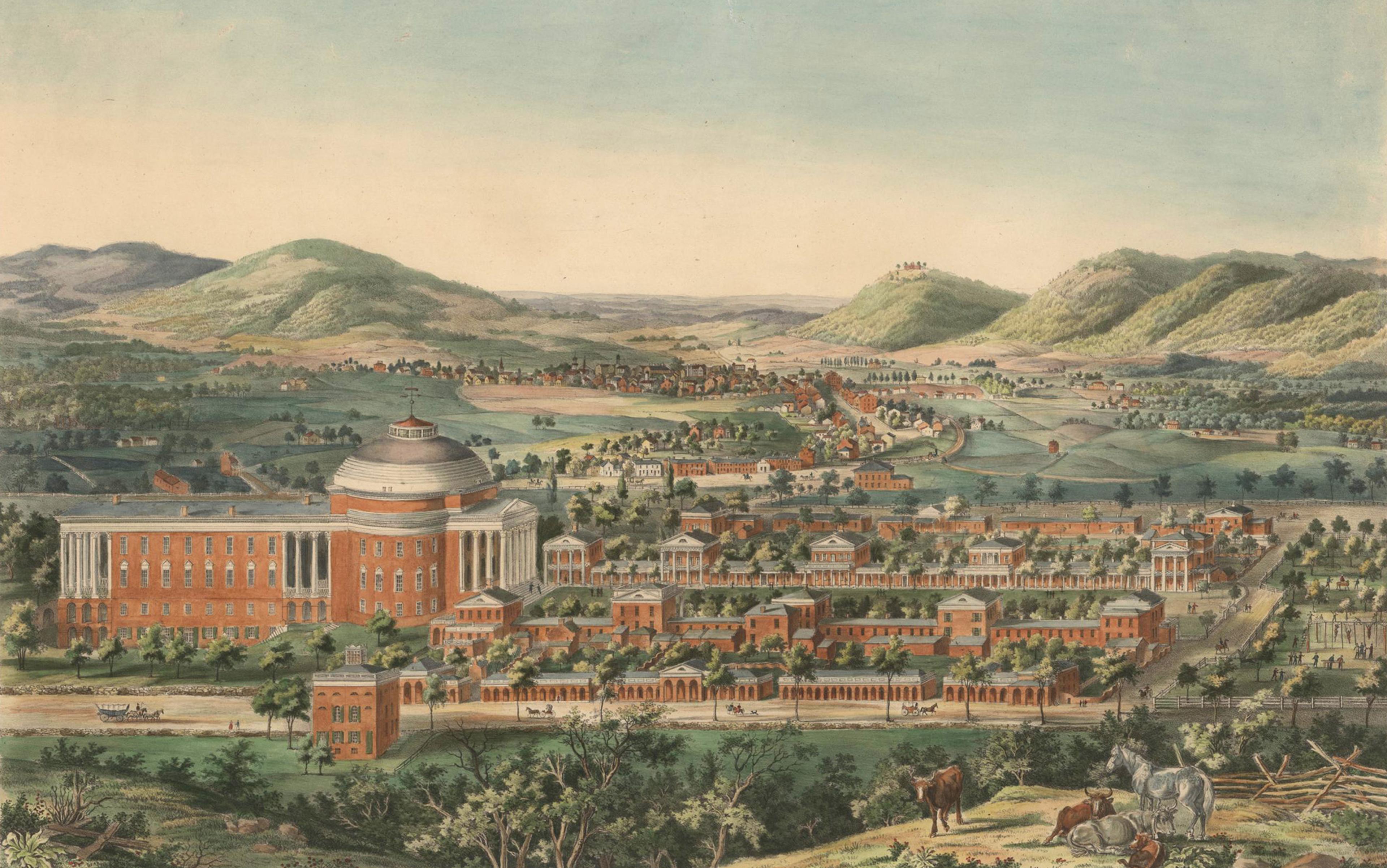

While African slaves spent countless days cooking, cleaning, being raped, beaten, sweating in the fields, and occasionally lynched, the children of their rich masters were being educated. The 1800s saw schools pop up all over the US, and by the end of the 19th century, free public education was available for all white children. Blacks have been in America since 1619 and received virtually no schooling until after President Abraham Lincoln decreed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. That is a 244-year head start given to whites – 244 years of exposure to scientific reasoning and philosophical thought, hundreds of years to discover the power of books and reading, and shape dreams into reality.

‘There’s a myth floating around that education is white culture, books are white culture,’ said Eric Rice, an expert in urban education, when I went to visit him at the Johns Hopkins University School of Education this year. ‘But African Americans have a long history of wanting education. The South had laws against teaching slaves to read, and people risked beatings and death trying to learn to read during slavery. There has always been a huge demand.’

The Lincoln administration made a conscious effort to right the wrongs in education along with other social injustices through the Freedmen’s Bureau, established in 1865. Charged with clothing, feeding, employing and otherwise helping the newly free people of colour become US citizens, it even had dispensation to grant land. The Reconstruction era in the US, those couple of years when the South was to rebuild itself from 1865 through 1867, would have been a great time to help blacks assimilate to the dominant culture through education. For the first time, the US was seeing the rise of black business owners, black politicians, and the black church, but our country didn’t capitalise on the opportunity. None of that success led to a spark in black schools.

Instead, Lincoln’s promises died with him that night at the theatre in 1865. Andrew Johnson, the next president, vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau renewal in 1866. He confiscated the land African Americans were acquiring in the South and gave it back to the white Southerners who occupied it before the war. From 1866 to 1869, Johnson depleted the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was eventually dismantled in full by his successor, Ulysses Grant in 1872.

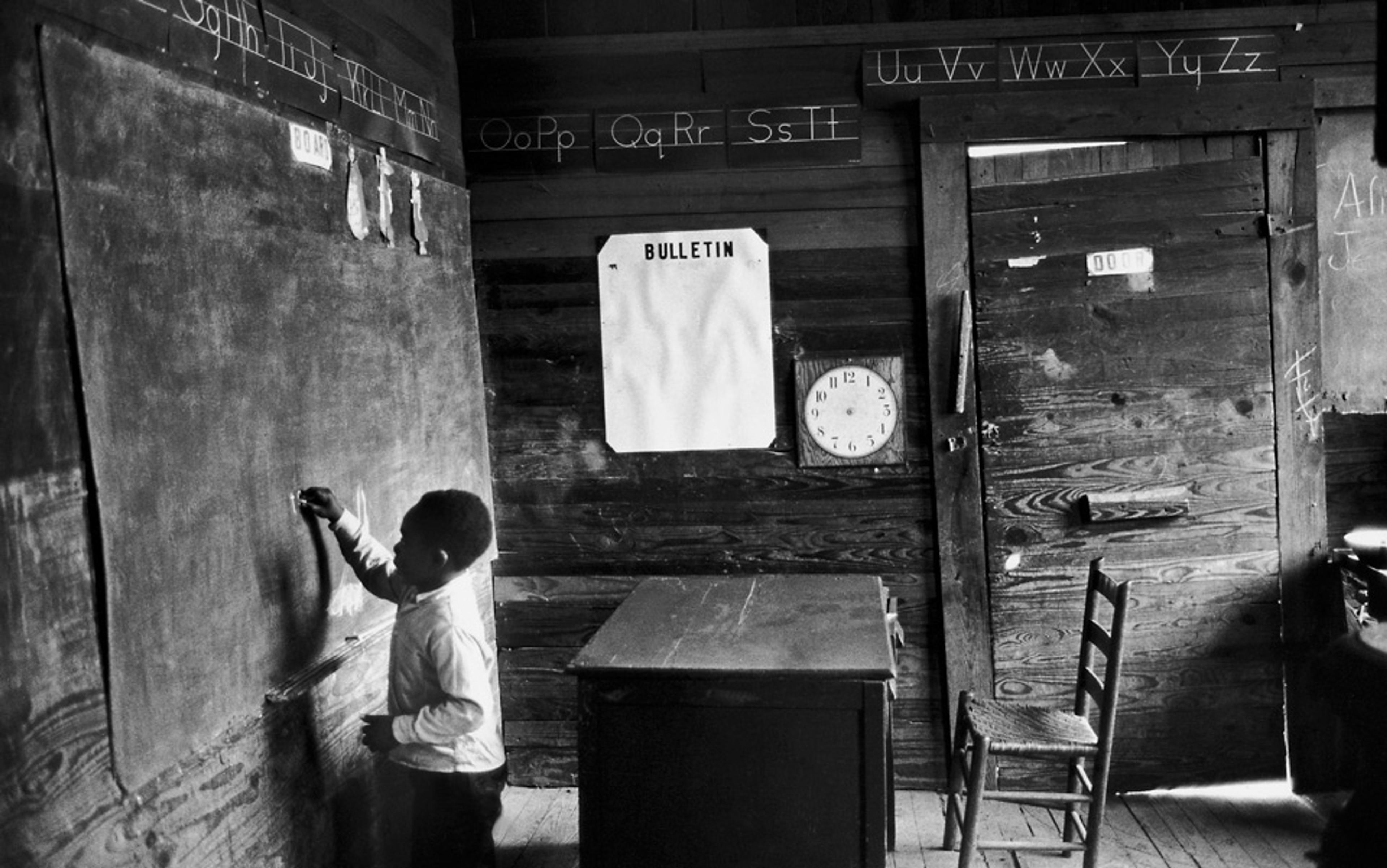

Sure, schools for freed slaves emerged. Within a year of emancipation, at least 8,000 former slaves began attending schools in Georgia; eight years later, those same black schools struggled to contain nearly 20,000 students. Scores of children piled into these shacks, trying to compete while dealing with broken or no desks, leaky ceilings and limited utensils.

‘Many of the early schools for black students received hand-me-down supplies and textbooks from white schools. The class sizes were larger and the teachers had fewer qualifications. The resources devoted to black schools were fewer and lower-quality than those devoted to white schools,’ Rice told me. We made it into the classrooms but not on the same level.

Jim Crow laws allowing racial segregation guaranteed that the gap would widen as years passed. By the end of the 19th century, 17 states and the District of Columbia required school segregation by law. Four others allowed the option.

That seemed poised to change when, in 1951, 13 families from Topeka, Kansas filed a lawsuit against their Board of Education. Like their ancestors, they wanted a quality education for their children – similar to what white children in the US had been receiving for decades. The case came to be known as Brown v the Board of Education and was a major victory in the fight for education for African American students. Brown v Board of Education showed an immense amount of promise, giving many blacks hope that the US could change. The landmark Supreme Court decision of 1954 overturned the Plessy v Ferguson verdict of 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation with a 9-0 unanimous decision declaring that separate schools for blacks and whites were unconstitutional.

They took their tax money, their resources, and their high-quality schools with them to the ’burbs

But the idea of blacks and whites being schooled together sent the nation into a frenzy. On 11 June 1963, George Wallace, Governor of Alabama, went as far as to stand in the door of the University of Alabama flanked by state troopers, so that black students couldn’t get in to register, standing down only after President John F Kennedy called in the National Guard.

‘White flight’ was the remedy for many Caucasians petrified by the thought that their child might share class with a Negro. They took their tax money, their resources, and their high-quality schools with them to the ’burbs. Blockbusting – the practice of pushing down property values in a neighbourhood through rumours of an imminent influx of some ‘undesirable’ group – and redlining – the practice of denying and charging more for banking services in an effort to racially construct a neighbourhood – were the most publicised means of keeping the races separate. Banks’ ability to accept and decline mortgages on the sole basis of colour were adjuncts to the effort, as well.

So there you have it; a combination of poor schools, institutionalised segregation, and minimal funding not only cultivated the deep roots of educational denial, but also strengthened the foundation upon which achievement gaps are built on today. The combination of all of these historical events led to what I call the Tradition of Failure. The tradition was not self-imposed. Obviously, African Americans can take some personal responsibility for the state of our race; however, many of us do not have a clue because we come from a tradition of people who never had a clue, leading all the way back to the day our ancestors left Elmina, the former slave port in Ghana that launched us on our turgid journey to this new world.

They did not have a clue what was waiting for them on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. Perhaps worse, we entered America as the lazy, ungrateful, enemy without even knowing why, and it has been an uphill battle full of limitless racial and social restraints every step of the way. We didn’t invent the idea of race or conceptualise the theory of free labour and what it could mean on a global scale. We just did what we were forced or told to do, and have been paying the price ever since.

The biggest price has been something that even my slave ancestors might never have imagined: while education was being withheld from blacks, the prison doors were wide open and welcomed us with open arms. The Ohio State University civil rights attorney Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow (2010), writes: ‘The criminal justice system was strategically employed to force African Americans back into a system of extreme repression and control, a tactic that would continue to prove successful for generations to come.’

The pipeline from school to prison has been a hot topic in the US and the subject of many lectures and debates. M K Asante, who wrote about this loop in Buck (2013), his memoir of inner-city Philadelphia, says his own public-school experience forced many of his friends into the streets. ‘There’s a toxic, incestuous relationship between pipeline schools, prisons and the politicians whose campaigns are funded by corporations that directly benefit from mass incarceration, prison labour and contracts, all at the expense of black lives. Black schools are a part of the prison industrial complex,’ he contends. Asante thinks that pipeline schools run through poor urban communities strictly to prepare black students for prison. ‘Grade school is supposed to prepare students for college or a trade. So think about it, there’s bars on the windows, prison-like guards, and metal detectors! Every thing is institutionalised just like a jail. The combination of these elements make up a breeding ground for prison.’

I thought about the things I saw as I entered Butta’s school and asked about the role corporations play. ‘Prisons are being privatised now, and a poor education in combination with other factors that exist in poor-black communities are making black failure profitable [for those companies],’ Asante contends.

He asked the question in his memoir in the chapter ‘The Pipeline’: ‘If schools look like prisons and prisons look like schools, will we act like students or prisoners?’

The ambience that created my schooling experience explains why many of the people I went to middle school with didn’t make it to high school. And even though I finished, the bulk of my surroundings and influences make me feel like a transition into a life of crime is easier than reading on grade level, which sounds crazy, but it might be true.

I don’t know what percentage of kids Butta’s age sell drugs. But in April 2014, our hometown paper, The Baltimore Sun, reported our city’s educational achievement: ‘According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress exam, only 7 per cent of black boys in Baltimore City schools are reading at grade level in 8th grade. Even worse, in Maryland, 57 per cent of black males are currently graduating from high school compared to 81 per cent for white males. Hundreds of black boys drop out of Baltimore high schools each year. They enter the adult world unable to read and comprehend the daily newspaper or to find a job that supports the cost of food and shelter.’

Something is missing in a large number of the predominantly black schools in the US. Whatever that missing ‘thing’ is, the streets seem to fill the void. The streets provide an education in everything that many of these schools don’t, such as survival skills, kinship, moneymaking opportunities, and love. A love that is absent from the cold hallways of schools such as the ones Butta, myself and millions of other African Americans attend.

There are schools in Philadelphia that are packed with rodents and hold classes with as many as 50 students

Butta’s school has been shut down along with a few other troubled city schools since my visit. He now must attend another school in a different district full of the kids who already attended, in addition to the new students who are being packed in because their school was shut down, creating an even worse climate. Butta’s new school is almost the same as his old one. He’s receiving a semi-education now; even more schools in Baltimore are closing this year following Maryland’s new republican Governor Larry Hogan’s massive proposal to cut $35 million from Baltimore Public Schools, meaning that classes could become more crowded and all of these issues could get worse. This isn’t just a Baltimore issue. There are schools in Philadelphia that are packed with rodents and hold classes with as many as 50 students.

Too often I hear people cry: ‘Our schools are broken, our schools are broken!’ But are they? Are our schools broken or is our system working perfectly for its creators? During the years I pursued a master of science in education at Johns Hopkins, I studied a theory called ‘social reproduction’, the brainchild of a Connecticut sociologist named Christopher Doob. His theory holds that we’ve got to produce a certain number of minimum-wage workers and inmates – a general collection of bottom-feeders – for capitalism to sustain, and so we build the social structures to keep that going.

‘Social reproduction is a real thing,’ Rice tells me, ‘but I don’t think it’s intentional. The system tends to produce the people who are needed for the jobs that will be available. We hear all of this talk on how we need to teach critical thinking because the jobs of the future will be in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and computer science, but actually a huge number of jobs in the future will be in fast food, different service industries and many fields that don’t require critical thinking. I’m not saying that a small group of people are planning this; however, it strikes me as interesting that we continue to produce a huge number of people fit for these jobs and they tend to come out of these school systems.’

Schools such as the one Butta and I attended are funded by property taxes from neighbourhoods full of housing projects and boarded-up homes, where the poor pay to perpetuate their own misery. The age-old system, in conjunction with law enforcement, makes the pipeline from public school to prison a reality.

I agree with Rice: I’m sure we won’t find a room full of rich white men from the top 1 per cent planning to flow through the pipeline $5,000 bottles of champagne and hors d’oeuvre, but I think the system perpetuates itself. It’s easy to think the whole idea of social reproduction is a drummed-up conspiracy theory, that it isn’t real, but I feel sure it is. How can it be otherwise when the US – arguably the world’s capital of innovation – doesn’t aggressively address this problem from the top down.

And I would challenge anyone who disagrees to walk through the schools in the neighbourhoods where I grew up; if we don’t need to fill up the prisons with more of Baltimore youth, then why don’t we fix the schools now?

I applaud pioneers such as the charter-school pioneer Geoffrey Canada who recognised the disparities in education in the African American community and made an honest attempt to address them from the bottom up by creating schools that shattered the norms. To date, his Harlem Children’s Zone has produced multiple senior classes with over 92 per cent four-year college acceptance rates. Many charter schools across the US have adopted Canada’s model along with other new models that focus on creating college-ready kids and reported success. So if it works, why can’t his models be adapted in all public schools? Why can’t we evolve pedagogy and reach for even higher levels of success?

I posed this question to Rice, who also sits on the board of two charter schools in Baltimore. ‘Geoffrey Canada’s success has a lot to do with his ability to raise funds. He’s found donors and supporters who traditionally don’t want to give money to school systems. I don’t know if that is a sustainable way to solve the bigger problems in entire urban districts. For me, if we really want to solve education, we need to decide to solve issues in poverty, all of the associated health problems, and employment challenges.’

Rice is speaking a language that reverts right back to the root of all the educational issues our country faces. The idea that communities are structured to create generations of snubbed students who go on to create generations of snubbed students makes the idea of social reproduction real.

Revamping the public school system is just half the battle, says Celia Neustadt, founder of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor Project, a non-profit that works with schools and teens and specialises in social change. Neustadt says her project’s success comes from stepping outside the system. ‘The young people I work with are confronted by the reality of supporting their families and keeping them safe,’ she says. To help such teens succeed and make it to college, a radically different toolset must be employed.

We were born into a permanent recession where making $20 last a week is not a miracle – it is a way of life

We’re quick to say that the US is a fair place where anyone can excel, but that’s not true. We need to acknowledge the failure so entrenched in history we cannot see it clearly, let alone root it out. African Americans are not stupid underachievers. Our accomplishments in science, innovation, athletics, business and politics are extraordinary – especially when you consider the countless constraints. As a matter of fact, we should be judged by our survival skills. I remember asking my friend Ron from West Baltimore about the recession after the market crashed in 2008, and he laughed: ‘Recession? What recession? Everything is the same round here!’ In fact for us it was an equaliser in some ways – people outside our communities were starting to feel the pain we’re used to.

We were born into a permanent recession where making $20 last a week is not a miracle – it is a way of life. Ovens are frequently used to heat up homes, everyone works under the table, and a new hustle is created every day.

A given: African Americans want to learn and be inspired like anyone else. Scholars can help bridge the achievement gaps, but only if they take the time to see what these students are up against. My own way of tackling the problem is through literacy. I want to get more people in low-income neighbourhoods to develop a love for reading by creating literature that speaks directly to poverty-stricken people and encourages them to write.

But we all have a moral obligation to set things right. We are all responsible for challenging the system and forcing it to create a fair learning experience for all students because we are dealing with more than just a failed school system or a broken home, or even millions of broken homes: we are dealing with failure on a historic scale, spanning hundreds of years. Acknowledging that we face this kind of epic failure is the first step in bringing about real change. That’s the big challenge in the US, where accepting failure has never been our strength.

No one can do everything, but if we follow the Ethiopian proverb ‘When spiders unite, they can tie down a lion’, we’ll have a better chance of solving these issues together and creating a nation that lives up to its founders’ dreams of truly offering success.