In the early 2020s, a trend called ‘gentle parenting’ gained popularity among millennial parents, and I quickly found my friends who are parents of young children getting wrapped up in it. My high-school best friend Macy, mother of two boys aged two and four, explained over coffee that she tries never to say ‘No’. Midway through our two-hour catch-up, the older one threw a small fist when she stopped him from tipping the sugar bowl into his milk. ‘I can see you’re upset because you really wanted to pour the sugar yourself,’ Macy said calmly. ‘But sugar isn’t for pouring right now. How about you stir your milk instead?’

Always validate the child’s feelings, prioritise warmth at all costs, and avoid negative words such as ‘no’, ‘don’t’ or ‘bad’ – that’s how Macy explained gentle parenting to me. This certainly isn’t how she and I remember our mothers parenting us in 1990s Hong Kong. Before Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (2011) scandalised Western readers, Chinese parents were already infamous for their strictness – corporal punishment for wayward and defiant children, academic excellence as non-negotiable, and ‘No’ delivered once, sharply, without negotiation or explanation. Macy laughed ruefully: ‘My mother would have given me one look and I’d have known to sit still. Now I’m reading articles about how saying “no” damages my sons’ self-esteem.’

My friend learns everything about parenting from books and Instagram reels, not her own mother. And gentle parenting certainly isn’t the only parenting philosophy trending among young mothers these days. AI-powered apps like Glow Baby, which has garnered more than a million downloads, help mothers track milestones and manage feedings, while also providing personalised recommendations tailored to each baby’s needs. Sleep training divides into warring camps: cry-it-out advocates cite studies on self-soothing. Attachment-parenting proponents warn of cortisol damage – harm caused by prolonged, high-stress hormone levels. There’s also the age-old breast versus bottle debate, repackaged as ‘fed is best’ versus ‘breast is best’.

All of these purport to be ‘science-backed’, but there’s no shortage of backlash against the philosophy. The journalist and mother Polly Dunbar writes in The Independent that gentle parenting is a set of rules regulating the behaviour of parents, not children. She worries that this kind of parenting raises a generation of spoiled brats who prioritise their emotions and needs over those of others. Psychologists also argue that validating emotions doesn’t essentially solve the child’s behavioural problems.

I have not sent these articles to Macy, lest she beats herself up for doing it all wrong yet again. But what may be oddly reassuring is that mothers have been getting it wrong for a while, as motherhood has long been a profession requiring credentials no mother could ever fully possess.

The paradox facing my friend (and many mothers across the globe) wasn’t invented on Instagram or TikTok: ‘mothercraft’ in the hegemonic, Western sense was engineered more than a century ago by Victorian-era experts who convinced mothers they couldn’t trust themselves. ‘Good motherhood’ has since become a moving target that tracks social class and institutional power more than biology or care, with poor, working mothers and mothers from racial minorities bearing the brunt of motherhood surveillance. This invention of maternal standards transformed motherhood into a mechanism for controlling not just children’s development, but women’s bodies, choices and lives.

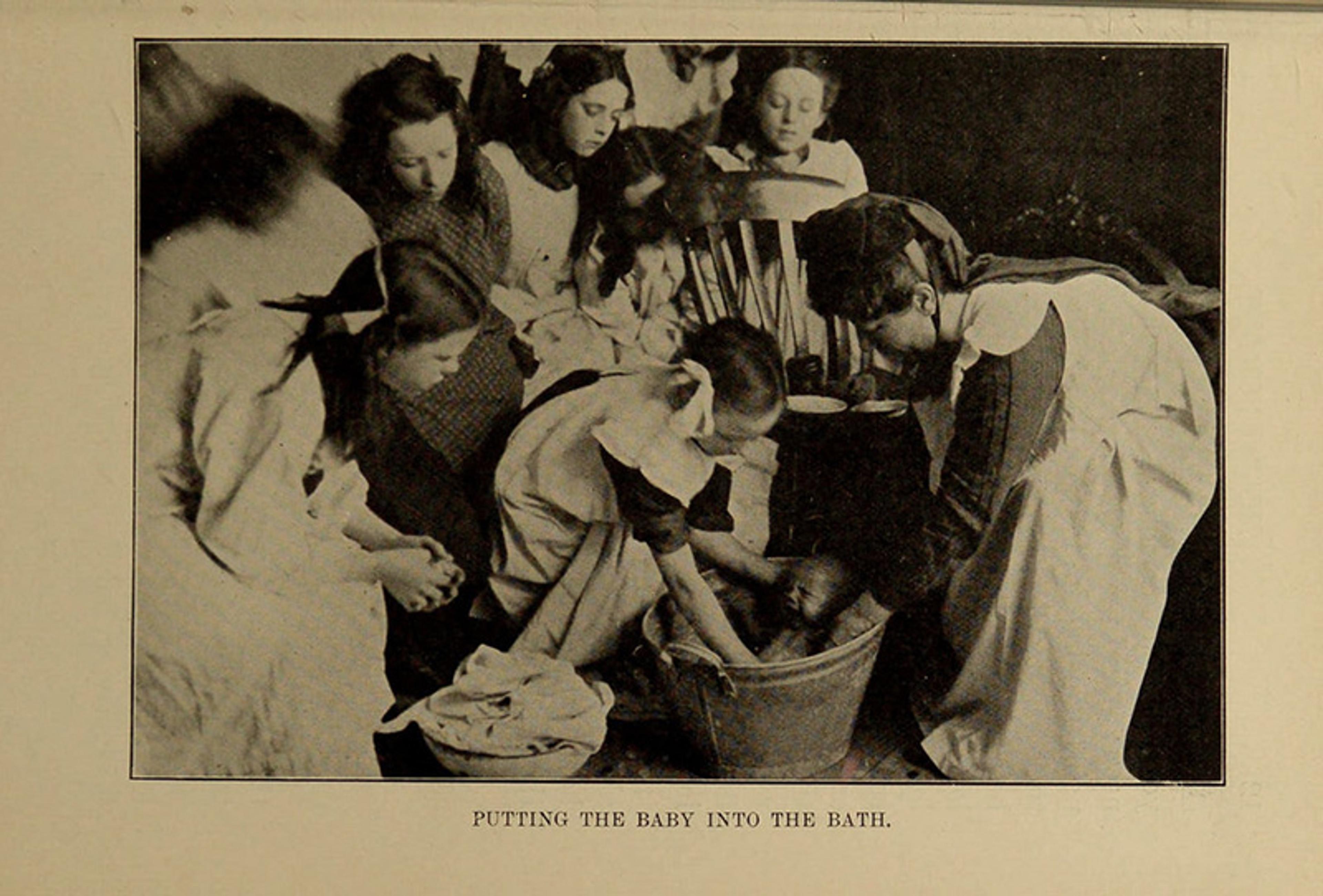

Seen in this light, today’s anxieties echo a much older project – one that began when mothering was first recast as a science. With her book Mothercraft for School Girls (1914), Florence Horspool, an inspector for midwives in Swansea in Wales, was doing something both revolutionary and ominously familiar. Her guide reads like any parenting bestseller on Amazon today: the correct way to bathe a baby, developmental charts, nutritious recipes. Horspool, also honorary secretary at Swansea’s Mothers’ and Babies’ Welcome, was writing a manual not merely for her 12- to 14-year-old students. She was codifying a revolution in the making: the transformation of private maternal care into public policy, the conversion of kitchen wisdom into classroom curricula.

From Mothercraft for School Girls (1914) by Florence Horspool. Courtesy Wellcome Collection

Horspool’s classes, like the other mothercraft classes that sprang up in England’s urban and industrial centres during the Edwardian era, were a direct response to the national call to train better mothers to raise the nation’s children. Britain had emerged victorious from the Boer Wars (1880-81; 1899-1902), but the victory was shadowed by staggering losses and a humiliating revelation of national weakness. When patriotic Britons willing to fight for the nation rushed to army recruitment centres in great numbers, recruiters found that these men lacked what it took to survive a war, or even a weeks-long sea voyage to reach it. The 860-page Report of the Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration (1904), chaired by Almeric FitzRoy and commissioned to investigate why British men were too frail for war, states that in Manchester, England’s industrial hub, 75 per cent of recruits had been turned away as unfit for duty. The national rejection rate reached a staggering 40 per cent for a war that had relied heavily on volunteers.

It included charts for tracking infant weight gain, and warnings about the dangers of old wives’ tales

This crisis of physical unfitness sparked what contemporaries called ‘the campaign for national efficiency’, and a need to discipline mothers: the term ‘mother’ appeared 1,102 times in the FitzRoy report. The committee had identified the usual suspects: industrial pollution, slum housing where nine children were packed into one single room with their parents, contaminated water supplies, grinding poverty. Yet, though the committee recommended tackling factory pollution and housing reform alongside maternal education, it was motherhood that captured the imagination of public health officials and became the primary focus of intervention. The pursuit of physical efficiency would be achieved not through structural reform, but through the creation of more efficient mothers: school girls were recommended to be trained on infant feeding and management, mothers to be lectured on the importance of milk being heated to 40 degrees Celsius, and ‘ladies’ health societies’ to be established nationwide to nurture women qualified to raise the nation’s men.

Even so, Horspool admitted that her mothercraft classes were met with criticism; even back then, 12 was considered too young to be taught the craft of motherhood. Yet, as Horspool wrote in her preface, working-class girls were already helping their mothers to nurse younger siblings, and ‘the teaching of Mothercraft simply means teaching them what they already know and practise, but know and practise badly.’ Horspool was satisfied with the results of her classes: ‘These future mothers … will not be the victims of ancient custom, indeed they … will continue to regard the education they receive at the Mothercraft classes as of superior authority to the advice of a past generation.’

Horspool’s instructions were not suggestions but imperatives: babies must be weighed weekly, fed on rigid schedules, and bathed according to precise protocols. The text included detailed charts for tracking infant weight gain, and explicit warnings about the dangers of old wives’ tales.

Through manuals like Horspool’s, maternal care had been transformed from a private domestic skill into a matter of state concern. And, as the gospel of scientific motherhood took hold, next came its apparatus – the careful sorting of worthy mothers from worthless mothers. The influential 1913 report by I G Gibbon for the National League for Physical Education and Improvement crystallised the logic: Schools for Mothers should focus on the ‘respectable’ working poor – those with irregular but steady work – rather than waste resources on what he called the ‘idle and vicious’ classes below them. The evangelical fervour of maternal education drew a new moral boundary and demanded its own doctrine of election: some mothers could merit the state’s pedagogical grace, and some should be abandoned to their ignorance.

Public health legislation didn’t have to explicitly name class to enforce it. Middle-class mothers, with their private doctors and well-stocked nurseries, existed outside the range of municipal health visitors and school inspections. Working-class mothers, by contrast, were visible: their children attended public schools where medical officers recorded weights and teeth; they gave birth in municipal maternity wards; they lined up at infant welfare centres for cod-liver oil and lectures on the dangers of traditional remedies.

Once these mothers were in the system, health visitors, functioning like foot soldiers, would make sure they stayed in it. These agents were trained in the principles Horspool had codified for schoolgirls. Their job was to cross the literal threshold of the working-class home, notebook in hand, and translate public health policy into domestic practice – while reporting back on what they found in the households. They counted heads in cramped bedrooms, noted dampness on the walls, and enquired whether the baby was being breastfed ‘on schedule’. They could recommend a child for medical treatment, but they could also flag a mother for neglect. Officially, they were there to advise; unofficially, they were the state’s eyes and ears in the kitchen and the scullery. (Infant mortality began a major, long-term decline around 1900 but, ironically, not because working-class mothers were being trained. Public health officials today attribute dramatic increases in infant health to the introduction of clean water, sewage systems, pasteurised milk, and basic hygiene informed by germ theory. These public-health improvements dramatically reduced the infectious diseases that had been the leading killers of infants.)

For women, now primed to aim for the ideal of ‘good motherhood’, there was no escape. Consider this: at the turn of the century, the moral panic of infant death by ‘overlaying’ – the accidental smothering of infants who slept in the same bed with their parents – consumed the minds of infant welfare enthusiasts. The number of deaths from overlaying was small – the rate in 1911 was only 1.4 per 1,000 – but the incidents attracted a disproportionate amount of attention. The authors of a 1903 article in The British Medical Journal blamed ‘drunken, careless, or incapable’ mothers for this kind of infant death. The solution was simple: a separate cot for the baby. In 1906, The Lancet insisted that any ‘sober, kind-hearted, and hard-working’ parent could devise some kind of cot with ‘a little self-denial’.

Public health officials created a system that could blame women for the structural failures of industrial capitalism

The fact that most working-class families could not afford a separate mattress, cot and blanket for the baby was not a concern for these maternal and infant welfare societies. In her book Round About a Pound a Week (1913) – the Nickel and Dimed of Edwardian Britain – Maud Pember Reeves documented how, for families surviving on a pound per week (just under $5 at the time), sharing a bed with infants simply made economic sense. Her study of poor families in Lambeth in south London revealed a broader pattern: the gap between expert advice and economic reality. Many children never tasted milk once weaned, but this had nothing to do with maternal ignorance. As Reeves explained: ‘The reason why the infants do not get milk is the reason why they do not get good housing or comfortable clothing – it is too expensive.’

The Tabard Estate, London, c1913. Courtesy London Picture Archives

The apparatus of maternal surveillance that emerged in Edwardian Britain was never really about saving babies – it was about saving the idea of the nation itself. By transforming motherhood from an intimate, embodied practice into a technical skill to be measured and monitored, public health officials created something unprecedented: a system that could blame individual women for the structural failures of industrial capitalism. The power of this invention was its apparent reasonableness. Who could argue against clean cots and regular feeding schedules? Who would defend ‘ignorant’ mothers against ‘scientific’ expertise? But scratch the surface of any maternal welfare programme, from the banana-crate cots to 40-degree milk, and the same pattern emerges: middle-class solutions imposed on working-class problems.

These ideals were modelled on a middle-class household with a breadwinner husband, separate bedrooms, running water, and money for fresh food. The same hidden assumptions shape today’s expert advice. When I think of Macy, her hands wrapped around a cup gone cold while her son flails at the café table, I realise that she too is being asked to perform a version of maternal perfection built for someone else’s circumstances: a mother with infinite patience, infinite time, and a private room for every tantrum.

As a movement, ‘scientific’ mothercraft coincided with British eugenics and the future of the white race. Francis Galton – Charles Darwin’s cousin and a polymath in his own right – coined the term ‘eugenics’ in his Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development (1883). Long before the phrase ‘scientific motherhood’ entered public health discourse, Galton had laid the intellectual groundwork for transforming mothering from instinct into science. His racial taxonomy distinguished between the ‘unassisted mother-wit’ – natural instinct without scientific guidance – in the child-rearing of Indigenous peoples, and the supposedly more evolved capacities of the civilised races – a framework that would soon be applied to British mothers themselves. In this schema, ‘good motherhood’ was implicitly white middle-class motherhood; the rest were cases to be educated, inspected or abandoned.

Before the 20th century had even dawned, medical officers of health were recording infant deaths in England. Some took note of the Gouttes de Lait (the Drop of Milk) initiative in France, which provided free sterilised cow’s milk while weighing babies and dispensing advice to mothers. A few similar programmes had been started in Britain with help from the Ladies Sanitary Association – the same women who had spent decades visiting the poor to distribute soap, disinfectants and religious tracts.

For years, these efforts remained firmly in the realm of private charity, reaching only those mothers willing to endure middle-class sermonising about cleanliness and moral conduct. The work was viewed as an extension of traditional ‘lady visiting’ – well-meaning but ultimately small-scale attempts to reform the habits of the poor through personal contact with their social betters. Before 1900, no one imagined that the survival of the British Empire might depend on whether working-class mothers properly managed their babies’ feeding schedules.

But after the Boer Wars, as Britain’s empire expanded into Africa and Asia, imperial necessity demanded that the state take control of what had been left to voluntary charity. And maternal instruction doubled as racial discipline: good motherhood meant white motherhood, and the ‘unfit’ mother, whether the poor whites in London or the ‘backward’ one in Lahore, marked the boundary of civilisation itself.

A dead baby might be a civic loss, but a surviving ‘defective’ one was a racial threat

What could replace ‘mother-wit’ as an effective tool to nurture more ‘efficient’ men? Galton found the answer in numbers. He developed a technique he called ‘pictorial statistics’, in which he overlaid multiple photographs of people who shared a trait to create a single composite image that he believed represented the group’s ‘average’ features. This was part of his broader effort to standardise the measurement and comparison of human traits. In a 1904 speech to the British Sociological Association, Galton lamented that eugenics was still treated merely as an academic topic. He argued that selective marriages – between people he considered socially fit – were efficient because: ‘What nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly, man may do providently, quickly, and kindly.’ Records of the discussion that followed show that the audience largely agreed with him.

By 1906, The Lancet was applying the same logic to British working-class mothers, dismissing their reliance on ‘traditions handed down from bygone ages’. What Galton had identified as racial backwardness was reconfigured as class-based maternal unfitness requiring systematic intervention. Edwardian public-health authorities consistently framed working-class mothers as threats to national wellbeing. As George Newman, Britain’s chief medical officer, insisted in Infant Mortality (1906), ‘the ignorance or carelessness of the mothers’ who worked in factories could explain the sorry state of infant mortality among their group. Included in their failings: ‘deficiency of exercise and exposure to inclement weather’.

The same evolutionary framework that positioned Indigenous peoples as primitively reliant on instinct now cast working-class British mothers as evolutionarily stunted, trapped in outdated customs that threatened the empire’s future. Newman even warned that ‘a high infant mortality rate almost necessarily denotes … degeneration of the race’. Some went further – Karl Pearson, an English biostatistician and mathematician, and a fierce protégé of Galton’s, insisted that some infants are better off dead, as by their very deaths they ‘offered the strongest possible presumption of inherent worthlessness.’ The moral arithmetic was brutal: a dead baby might be a civic loss, but a surviving ‘defective’ one was a racial threat. This logic made maternal ignorance not just a moral failure but a form of biological sabotage, a weakness that could be inherited.

Reformers across the English-speaking world gave this anxiety moral vocabulary. In the United States, prohibitionists and eugenicists joined forces to warn that alcohol, venereal disease, and even emotional excess were ‘racial poisons’. The maternal body became a frontier of national defence, its purity imagined as the bulwark against degeneration. Officials charged that ‘impure milk also threatened the survival and vigour of white babies.’ (It’s no surprise that the modern-day alt-Right in the US also uses milk as a symbol of racial purity) To be a good mother was to be biologically disciplined; to lapse was to endanger the empire: in Britain, the FitzRoy report warned that if a mother drank alcohol, ‘the future of the race is imperilled’. The empire’s public-health project thus merged moral hygiene with racial hygiene – its clean homes and pure-milk campaigns functioning as instruments of eugenic governance.

A temperance movement demonstration in Coatbridge, Scotland around 1912. Courtesy North Lanarkshire Council

The same surveillance that policed working-class homes in London was exported to the colonies under the banner of imperial hygiene. Colonial medical officers catalogued the fertility, feeding and supposed ‘instincts’ of Indian and African mothers, often comparing their ‘improvidence’ with that of Britain’s urban poor. As the historian Roberta Bivins notes, the management of colonised women’s bodies mirrored the management of the domestic poor: both were subjects of improvement, both blamed for endangering the health of the race. Maternal and racial hierarchies thus converged. The ‘unfit’ mother – whether the washerwoman in South Acton or the ayah in Calcutta – defined the limits of civilisation itself. The British state’s moral project to produce ‘better mothers’ at home became the template for its racial project abroad.

Victorian domestic ideology had already established the theoretical groundwork by enshrining motherhood as women’s natural and exclusive domain. The ‘angel in the house’ ideal positioned maternal instinct as both sacred and fragile, requiring protection from the corrupting influences of public life. This seemingly protective discourse created the conceptual space for its opposite: if good mothers were naturally maternal, then bad outcomes must indicate maternal failure. The doctrine of separate spheres thus provided the ideological foundation for holding women individually responsible for children’s welfare while systematically excluding them from the economic and political decisions that shaped family life.

Not having a baby doesn’t grant you a free pass from the cult of good motherhood. My father has been relentless in badgering my husband and me to have a child. ‘Your life won’t be complete without one,’ he says each time we talk. ‘And don’t you think it’s selfish to stay childless?’ I stay composed and remind him it’s a decision between my husband and me. He doesn’t pause before replying: ‘It concerns me – and your in-laws, and, frankly, humanity itself. After 30, a woman’s shelf life is over. What’s left, if not children?’

If my father’s words sound like a red flag, they probably are. But he is also the archetypical Chinese parent who wants the best for me: that I’d get excellent grades, collect degrees and accolades, establish myself in capitalist society, own a house, find a man of at least the same calibre and financial means to marry, then have kids. Now I’m one step away from the whole shebang. I used to think my father’s words belonged to his generation, a relic of Confucian family logic. But the older I get, the more I realise how little these scripts change, even if the vocabulary shifts.

Mothers must optimise their children’s development through constant vigilance and expert guidance

The script stems from the positioning of children as the centre of any family, often at the cost of the mother. In Centuries of Childhood (1960), Philippe Ariès argued that the modern concept of childhood as a sacred, separate stage of life – one requiring intense parental devotion and expert guidance – emerged only in the 17th and 18th centuries. Before this, children were integrated into adult life; afterward, they became the centre of an increasingly inward-focused family. But Ariès also observed something else: with childhood elevated to the status of ‘divine purity’, motherhood had become its priesthood. The divinity of the child demanded the subordination of the mother. What appeared to be reverence for children was, in practice, an instrument for regulating the behaviour of women.

Ariès’s book has garnered criticisms from medieval historians, but parts of it still ring true today. Contemporary motherhood operates under what researchers call ‘intensive parenting’ – a philosophy demanding that mothers optimise every aspect of their children’s development through constant vigilance and expert guidance. The five key beliefs of intensive parenting still echo Ariès’s thesis: parenting is best done by mothers; significant time must be invested to meet children’s needs; expert knowledge should guide decisions; resources must be devoted to stimulating activities; and children are inherently precious and innocent.

Across the world, the same script plays out in different costumes. In the US and the UK, it’s called gentle parenting. Globally, attachment parenting promises secure children but demands constant availability. Japan’s kyoiku mama (‘education mother’) and Korea’s eomma-pyo (‘mother’s brand’) is expected to orchestrate her child’s every academic success, while sociologists describe Western middle-class parents practising ‘concerted cultivation’, an equally labour-intensive choreography of lessons, sports and self-esteem. Each framework claims to liberate mothers through knowledge, yet all tighten the same knot: whatever they do, they can always do more.

The apparatus of scientific motherhood that emerged in Victorian Britain didn’t just create standards for child-rearing. It created a comprehensive system for managing women’s lives. The same logic that blamed working-class mothers for infant mortality also circumscribed what women could do, where they could go, and who they could become. And baby’s welfare never ceased to be the state’s concern, or even its key performance indicator. In the past few years, Taiwan’s ministry of health and welfare evaluated hospitals and local health bureaux on whether 50 per cent of infants were exclusively breastfed for six months, turning an intimate, time-consuming act into a national ‘gold standard’. The cult of intensive motherhood, dressed up in the language of children’s welfare, has always been a means of restricting women’s freedom.

The machinery never disappears; it only modernises. Where lady visitors once audited kitchens, employers and HR policies now monitor women’s bodies and productivity. In the United States – a country without a law on universal federal paid parental leave – only 13 states and the District of Columbia guarantee paid family leave through state programmes. As a result, many new mothers are pressured to return to work within weeks of childbirth, often while still physically recovering and trying to establish breastfeeding. At the same time, they are told by doctors, hospitals, lactation consultants, workplace-wellness programmes and parenting culture that exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months is the unquestioned standard of ‘good motherhood’.

The vocabulary has changed but the script remains. We no longer speak of ‘race suicide’ or ‘maternal duty to the Empire’, but the command to reproduce, to nurture, to be endlessly giving – these are simply newer versions of the same social contract that has bound women for centuries. What we call ‘motherhood’ has never been a private instinct; it has always been a public institution, one designed to manage women’s bodies, emotions and ambitions in the name of stability.