The popular Austrian tabloid Heute has a tradition of publishing pictures of the first babies born around the country in the new year. Vienna’s 2018 baby was a girl named Asel. She was born of Muslim parents. And she was received with hate.

‘Next terrorist born.’ ‘Deport the scum.’ ‘I’m hoping for a crib death.’ Hundreds of similar comments flashed across Austrian social-media sites in what has become a familiar piece of the news cycle not only in Austria, but across the Western world. Between 2013 and 2015, for example, Germany witnessed an 87 per cent increase in hate crimes, rising to its highest levels since the Second World War. In Spain, hate crimes surged from the low 200s in 2009-2012, to more than 1,100 in each of the years 2013 to 2016. In Poland, activist watch groups estimate that hate crimes rose 10-fold in the new millennium.

For a while, such trends were chalked up to an enduring Western anxiety over Islamic terrorism. But as Islamophobia increasingly becomes a single motive among many in these hate crimes, this story no longer holds up. Anti-Semitic crimes are rising dramatically all over Europe, including in typically more tolerant countries. Across the United Kingdom, anti-Semitic crimes rose 34 per cent from 2017 to 2018, hitting an all-time high. France witnessed jumps of over 20 per cent in both 2016-2017 and 2017-2018.

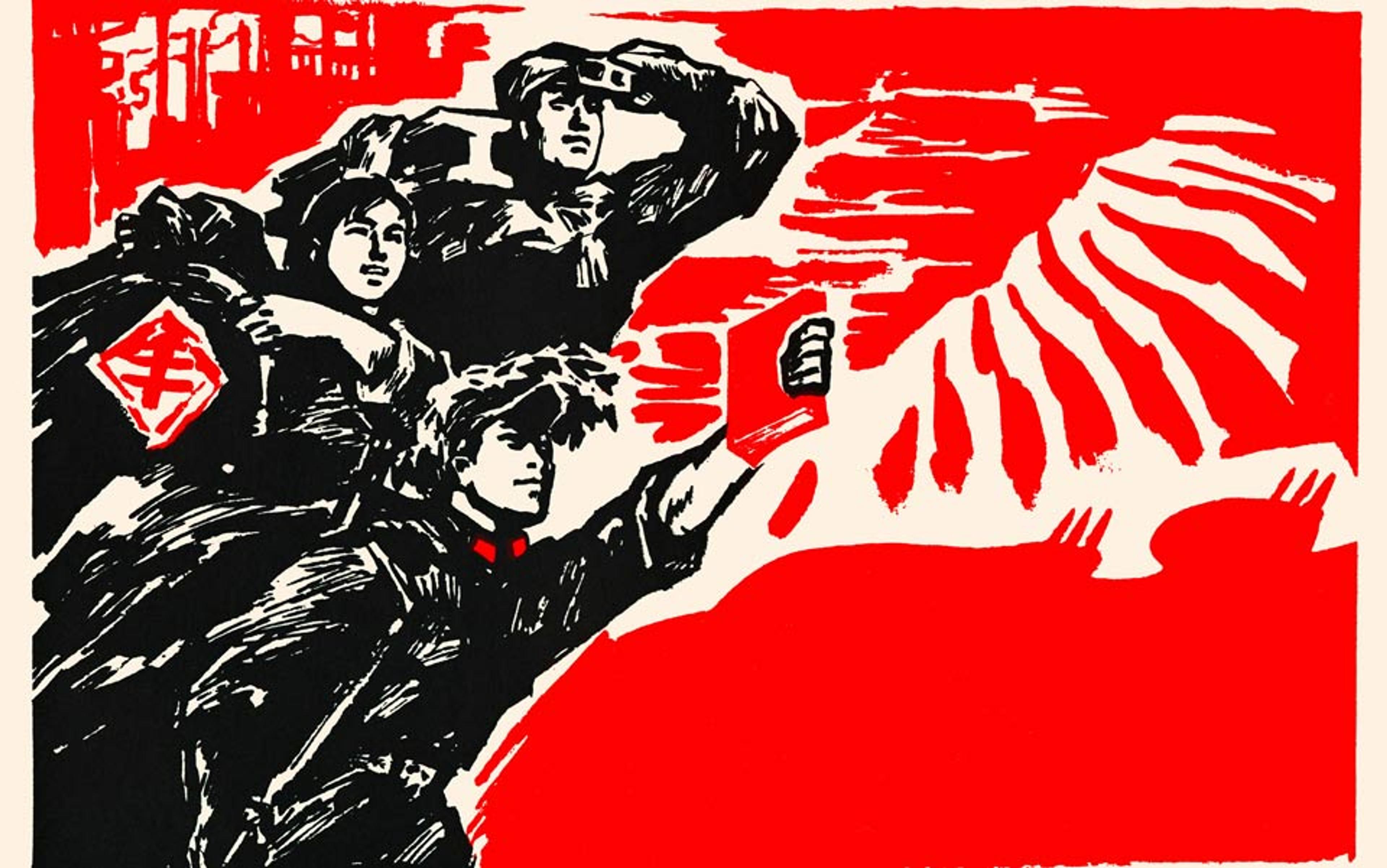

African nationals are also at increased risk. In Italy, where the far-Right nationalist association Forza Nuova now has more Facebook followers than Italy’s largest Left-wing party, a man recently drove around the town of Macerata shooting black immigrants from his car. In Poland – where the nationalistic Law and Justice party ascended to power in 2015 – Amnesty International reported the story of a man who, in 2014, was beaten with sticks in a nightclub by multiple attackers yelling: ‘Fuck niggers, fuck Jews.’ The man was actually Syrian. Two years later, 60,000 nationalists marched on Warsaw brandishing signs bearing slogans such as ‘Clean Blood’.

Meanwhile in the UK, in a sad reversal of malice, hate crimes against Polish people increased 10-fold in 2004-2014, and continue to make headlines. This April, a Polish man in Hull was chased by a gang of 20 men and beaten with a nailed plank of wood. Afterwards, his friend told reporters: ‘This sort of thing happens nearly every day to Polish people here.’ In Northern Ireland in 2015, Igor, an 11-year-old originally from Poland, was beaten so badly that, when his friend arrived to help, he didn’t recognise him. The attackers were other children, some as young as eight. As they beat Igor, they yelled: ‘You are Polish shit!’ ‘Go back to Poland!’

And then there is the United States, where such stories are turning up literally every day. In one incident this year, a woman was aggressively badgered by a white man in a park near Chicago for wearing a shirt printed with the Puerto Rico flag. She captured the incident on Facebook Live. ‘Why is she wearing that shit?’ the man snarled, while stalking after her. ‘You’re not an American citizen!’ The biggest news angle of the incident was the derelict response of the police officer present.

But other concerns were rightly raised. Some, like Luis Gutiérrez, the House representative for Illinois, alluded to the so-called ‘Trump effect’. Between the US president’s racially charged policies and his own willingness to use dehumanising language, Donald Trump has ‘unleashed’ (as Gutiérrez put it) a new tolerance for public expressions of bigotry – a claim given credence by a variety of empirical studies. Others argued that the Chicago incident should not be reduced to reinvigorated white supremacy, stressing instead that the US, like Europe, is now breeding general xenophobia. ‘Germany in the early 1930s wasn’t so different,’ stated one public comment. ‘This is how things start.’ Indeed.

However, Ricardo Rosselló, the governor of Puerto Rico, had a more philosophical take on the Chicago incident: ‘It’s an issue of education, it’s an issue of civil rights, and it’s an issue of basic human dignity.’ Notably, the same point was made by Caitríona Ruane, until 2017 a member of the Northern Ireland Assembly, regarding the attack on Igor: ‘All forms of hate crimes, whether it is racism, sectarianism or homophobia, are wrong … We have always hoped and expected that [families from other countries] would be treated with dignity and respect.’ And here’s Austria’s president Alexander Van Der Bellen speaking out against the slander hurled at the new year’s baby from Vienna: ‘All men are free and born equal in dignity and rights … Welcome, dear Asel!’

Incidents like the ones in Austria, Northern Ireland and Chicago contradict the contemporary Western dogma to treat every individual in a way that acknowledges his or her worth as a human being, regardless of their port of departure. And yet, this dogma is delicate. Not just because human dignity seems presently jeopardised by some kind of ‘Trump effect’, or even by some broader reawakening of authoritarian sympathies across the Western world. No: the very concept of human dignity is tenuous.

Dignity has three broad meanings. There is an historically old sense of poise or gravitas that we still associate with refined manners, and expect of those with high social rank. In this sense, dignity is almost synonymous with ‘dignified’. Much more common is the family of meanings associated with self-esteem and integrity, which is what we tend to mean when we talk of a person’s own ‘sense of dignity’ or when we say, for example, ‘they robbed him of his dignity’. Third, there is the more abstract but no less widespread meaning of human dignity as an inherent or unearned worth or status, which all human beings share equally. This is its moralised connotation, and what I’m interested in here.

This moralised connotation is implied in the couplet ‘human dignity’, one that picks out the ‘basic’ kind of worth that Puerto Rico’s governor was pointing to. ‘Basic’ doesn’t mean ‘simple’ – as if the value in question were less important. It means ‘fundamental’. It is the kind of worth everyone has, and has equally, just because we are persons.

This fundamental worth is usually taken to be distinctive in some sense. Sometimes, this distinctiveness has been expressed by the claim that humans are supremely valuable. The chorus in Sophocles’ Antigone, for example, praises man as the most ‘wondrous’ thing on Earth, a prodigy cutting through the natural world the way a sailor cuts through the ‘perilous’, ‘surging seas’ that threaten to engulf him. But in modern discussions, dignity is usually said to be distinctive in the sense that it is incommensurable: it can’t be exchanged for other kinds of worth. The most influential expression of this modern idea comes from Immanuel Kant in Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals in 1785:

Whatever has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; on the other hand, whatever is above all price, and therefore admits of no equivalent, has a dignity.

Kant correspondingly argued that we have a categorical duty to treat other human persons ‘always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means’. In other words, the distinctive value of dignity demands a special kind of respect, which we express through a self-imposed restriction on our deliberations about what to do or say.

So, why think the concept of human dignity is tenuous? In the first place, it is very young. The term is not in any existing copy of the Magna Carta (1215). It does show up much later in the English Bill of Rights (1689), but not with a moralised meaning. People were not yelling ‘Liberté, égalité, dignité!’ during the French Revolution. And for all its fiery rhetoric about equality and ‘inalienable’ rights, the US Declaration of Independence does not speak of human dignity. Nor does the US Constitution.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights used dignity to justify itself: a conceptual watershed

You won’t find any moralised talk of human dignity in any of the old slave narratives. And it isn’t in the passionate abolitionist speeches, pamphlets and newspaper editorials of the 19th century. Ditto for suffrage. Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Susan B Anthony, Jane Austen, Harriet Beecher Stowe: none used the term much, and almost never with its moralised meaning. In fact, until at least 1850, the English term ‘dignity’ had no currency as meaning anything like the ‘unearned worth or status of humans’, and very little such currency well into the 1900s. When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) used the terminology of human dignity to justify itself, this turned out to be a conceptual watershed. We have not been talking about human dignity for long.

There are some fascinating exceptions in the early modern intellectual canon, but they don’t change the timeline. Kant’s German term Würde was indeed rendered as ‘dignity’ by even his earliest translators. However, his ethical philosophy was very slow to gain traction, especially beyond the German-speaking world. He enjoyed a flash of popularity in England around 1790, but little of that was for his ethics, and it faded by the end of the century. Anglophone interest in Kant began to reemerge around 1820 but, again, not for his practical philosophy. In fact, the Groundwork wasn’t professionally translated until 1836. And even that translation wasn’t easily available until a revised edition appeared in 1869.

Or consider Kant’s predecessor, the French polymath and mastermind of the celebrated Encyclopédie (1751-1766), Denis Diderot. Diderot was working towards his own conception of human worth. In his view, our basic moral status is what justifies our individual rights. However, this status also places us under a duty to respect the status and rights of others. This is because, according to Diderot, one’s basic moral status is realised through social participation in a community:

It is for the general will to determine the limits of all duties. You have the most sacred natural right to everything that is not resisted by the whole human race … Say to yourself: ‘I am a man, and I have no other truly inalienable natural rights except those of humanity.’

Later in the same Encyclopédie essay, Diderot even used the French term dignité (instead of humanité) to explain the kind of shared status in question. However, both Diderot’s moral philosophy and terminology never took on, and he remains a fairly obscure figure today.

Diderot was building on the views of the 17th-century German jurist Samuel von Pufendorf, which went something like this: we reciprocally assume one another’s basic moral status – I of you, you of me – whenever we interact. This assumption is conceptually implicit in any exchange between us. This is because, whenever we address another person directly – for example, with a claim like ‘You must allow me to speak’ – we already treat them as an accountable, responsible being. That is, we treat them as capable of being responsible to us, for that claim. Otherwise, why address them at all? Moreover, like Diderot, Pufendorf in Law of Nature and Nations (1672) uses the term ‘dignity’ to bring these ideas together:

There seems to him to be somewhat of Dignity (dignatio) in the appellation of Man: so that the last and most efficacious Argument to curb the Arrogance of insulting Men, is usually, I am not a Dog, but a Man as well as your self. Since then Human Nature is the same in us all, and since no Man will or can cheerfully join in Society with any, by whom he is not at least to be esteemed equally a Man and a Partaker of the same Common Nature: It follows that, among those Duties which Men owe to each other, this obtains the second place, That every Man esteem and treat another as naturally equal to himself, or as one who is Man as well as he.

It’s moving prose. However, once again, it never eventuated in any established terminology. Pufendorf was virtually forgotten by the end of the 18th century.

Are the roots of dignity really so shallow? How we answer this depends on what we take as the measure of success. If we want some unambiguous historical basis for the way we talk about human dignity today, then we will be disappointed. There are certainly some alternatives on offer – especially coming from the Christian tradition – that deserve mention.

Since about 1950, there has been building interest in the Christian Renaissance writer Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and his Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486). By the end of the 20th century, Pico and his Oration were routinely being praised in history textbooks of various stripes in the most superlative terms. And it is now common to find Christian theological treatments of human dignity that laud Pico for his genius on the subject. However, as the medievalist Brian Copenhaver has recently shown, this is all highly ironic. For a start, the Oration was condemned in its own day, and Pico himself was forgotten for most of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Even the title of the text postdates Pico. More to the point, Pico’s Oration isn’t about dignity in the moralised sense. It uses the Latin term dignitas only twice, and, as Copenhaver states: ‘in neither case does dignitas belong to humans, except aspirationally’. Instead, the term denotes angelic rank, which makes sense since Pico’s aim is to argue that humans must escape the body and turn into angels. This is not our moralised idea of basic human dignity.

Another widespread error is the claim that our idea of human dignity can be traced to the Biblical doctrine that God created humans in his image, more commonly referred to as imago Dei. There are many early Christian writings from late antiquity to the Middle Ages that discuss this idea, and many that talk about the ‘dignity’ of various beings and things. But they are not about some kind of basic worth that, as the scholar Bonnie Kent recently put it, ‘all people have just because we are human, or because humans are created in God’s image’. On the contrary, she explains: ‘As the creation story came to be understood in the Latin West, it was only the beginning of a narrative of humankind’s sin and redemption. [And that] narrative is predicated on the assumption that human nature is mutable.’ In other words, human nature was ‘so badly deformed by the Fall that it needs to be reformed in the likeness of Christ, the second Adam’.

Beyond its youth, there is another reason our concept of dignity is tenuous: it comes with a peculiar existential challenge. To appreciate this challenge, start by considering that the relative youth of our concept of human dignity is juxtaposed by its present ubiquity. The moralised concept of dignity is a cornerstone of our contemporary Western ethos, standing shoulder to shoulder with other fundamental ideals such as liberty and equality. In everything from the aforementioned Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (1949), the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference (1975), the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000) and the constitutions of an array of modern states from Portugal to South Africa, ‘human dignity’ is literally ascribed as the basis of human rights. Judges appeal to it for similar effect in court rulings. Humanitarian agencies often cite it in their mission statements. And the oppressed the world over cry out in its name.

And yet, the idea of human dignity is beset by hypocrisy. After all, our Western ethos evolved from, and with, the most violent oppression. For 200 years, we’ve breathed in the heady aspirations of liberty and justice for all, but somehow breathed out genocide, slavery, eugenics, colonisation, segregation, mass incarceration, racism, sexism, classism and, in short, blood, rape, misery and murder. It shocks the imagination.

The primary way we have dealt with this shock and the hypocrisy it marks has been to tell ourselves a story – a story of progress. Made up of many chapters, and available in various versions, the story’s common hook is the way it moves the ‘real’ hypocrisy into the past: ‘Our forebears made a terrible mistake trumpeting ideas such as equality and human dignity, while simultaneously practising slavery, keeping the vote from women, and so on. But today we recognise this hypocrisy, and, though it might not be extinct, we are worlds away from the errors of the past.’ This story has sold especially well in mainstream white America.

It is tempting to talk of what we are ‘becoming’: it is another way of avoiding the worst of the present

Incidents such as those from Chicago, Austria and Northern Ireland lead us (or some of us) to reconsider this story. There is something increasingly mundane about them, which rightly frightens us into reflection, which we should certainly encourage. But this moment of collective reflection is not the existential challenge I’m trying to elucidate. Something subtler and decidedly more destabilising lurks just below.

The tempting move to make, when reflecting on the contradiction between our ideal of human dignity and the surge of bigoted and xenophobic hate crime in the West, is to sound an alarm about what we are ‘becoming’, or to emphasise the threats to human dignity that are ‘arising’. This is tempting because it is another way of avoiding the worst of the present. It ultimately dodges the possibility that the hypocrisy in our ethos never went away in the first place. The language of ‘becoming’ and ‘arising’ implies that there was some time when we lived in genuine mutual respect of one another’s dignity. Confronting this fallacy sets up the existential challenge: whatever ‘effect’ Trump, or any other political ideologue or extremist society for that matter, is having on the West in shifting us away from the ethos of human dignity, they are all more catalyst than cause.

A variety of examples could be offered to support this claim. And others have made similar claims in different contexts. But US race disparities make the point particularly well.

In the first place, economic inequality between whites and people of colour, which is one driver of this tension, had been growing steadily in the US long before Trump – since the Great Depression, actually. According to a major 2017 report from Prosperity Now and the Institute for Policy Studies, median black and Latino households witnessed 75 per cent and 50 per cent declines in wealth between 1983-2013, leaving them with a measly household wealth of $1,700 and $2,000 (respectively). Meanwhile, median white wealth grew to a whopping $116,800.

Or consider that Trump wasn’t seriously on the political scene when Black Lives Matter was born in 2013, after the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012. Ditto the tumultuous year that followed, when police killed Eric Garner with a choke hold in New York City; shot Michael Brown in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri; and shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio. At this time, Trump was still just exploring his options. More to the point, racial disparity has blighted US policing as long as anyone has bothered to keep records.

For example, black men who are arrested are six times more likely to be convicted than whites, and then sentenced to 20 per cent more time, for the same crimes. A 2014 study from the University of Michigan found that, again, blacks were 75 per cent more likely than whites to face a charge carrying a mandatory minimum sentence, for the same crime. Combined with the fact that incarceration has increased 500 per cent over the past 40 years, with the most significant increases occurring in 1980-2010, the end result is that, by 2017, one in every eight black men is in prison on any given day – that’s if he is not shot. A 2002 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that the death rates for black men were 4.7 times higher than for white men as a result of law enforcement in 1970-1988, and 3.2 times higher in 1988-1997. And a 2015 paper from the Harvard Chan School of Public Health showed that from 1960-2010, black men were always at least 2.5 times more likely to die than white men during episodes of police intervention. You can’t blame any of this on current politics.

To be clear, my point is not that we should pull back from criticising Trump or anyone else for practices that offend against human dignity. My point is that sincerely facing up to the hypocrisy in our Western ethos requires resisting the temptation to scapegoat both the past and the present. We must not divorce ourselves from the fact that the present is possible only because of our past, the one we helped to create. Likewise, the existential question isn’t, are we really who we say we are? The question is, have we ever been?

Let me suggest two responses to the challenges I’ve laid out. First, we might ask whether the concept of dignity had a life outside of and before it was connected to the term ‘dignity’? Put this way, it seems immediately plausible that it did. Even the range of other terms I’ve used so far – rights, worth, status, humanity, etc – give us possible starting points to track down the moralised concept without the actual term ‘dignity’. We still shouldn’t expect this to be unambiguous. Sophocles’ Antigone is a case in point. It didn’t use any obvious terminological clue. On the other hand, it did seem to be saying something about human dignity.

Second, even if the idea of human dignity is more tenuous than we’ve hitherto realised, there might be a silver lining to this admission. Namely, that the idea is yet malleable – open for reasonable debate and development. In other words, perhaps it is still up to us to say what this basic moral status is or entails, as well as what it is about being human that makes it true we have this status. To be sure, there is a danger in thinking this way. Once we start asking these kinds of questions, there is a risk of drawing lines between who or what ‘really’ has dignity and who or what doesn’t. But then again, we’ve been drawing these lines for some time anyway. Simply having the idea of human dignity on board hasn’t stopped us from leaving a wake of misery and oppression. So, maybe it’s time for more humility. Maybe if we assumed there is still much to learn when it comes to the idea of human dignity, we could do better. Maybe we could discover new depths, not only in the concept, but in our commitment to it.

This Essay was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon magazine from Templeton Religion Trust. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton Religion Trust.

Funders to Aeon Magazine are not involved in editorial decision-making, including commissioning or content approval.