The year was 1960, and Dr Stanley Milgram had a theory about Germans. Only 27 years old, Milgram was a rising star in social psychology. He had just finished his doctorate work at Harvard on the phenomenon of conformity and begun a prestigious professorship at Yale. For his first experiment as a full-fledged academic, he wanted to push the literature on conformity further, to make it less abstract. Ever ambitious, Milgram didn’t just want a bigger challenge, he wanted to recreate the Holocaust, to quantify and study it at the microscopic level. And unfortunately, he got his wish.

Milgram’s graduate dissertation on conformity followed the famed work of Solomon Asch, a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College. Asch’s 1951 experiment requires a small group made up of confederates (ie, knowing actors) and one unknowing subject. They are presented with a card with a single black line, then shown another card with three black lines of varying length. The participants must pick one line out of the three that matches the single line. It’s a task so easy everyone gets it right on their own, but in this experiment the unknowing subject goes last, after the confederates have all given the same wrong answer. Asch found that under these circumstances a third of subjects routinely conform by giving the incorrect response.

Milgram tweaked Asch’s experiment a bit – using auditory tone lengths instead of lines – and sought an international comparison. (He wanted to use Germans, but his adviser persuaded him to use Norwegian and French populations instead.) The results would go on to be published in Scientific American, but Milgram was unsatisfied. This is how he described his thinking at the time to Richard Evans in The Making of Social Psychology (1980):

One of the criticisms that has been made of [Asch’s] experiments is that they lack a surface significance, because after all, an experiment with people making judgments of lines has a manifestly trivial content. So the question I asked myself is, ‘How can this be made into a more humanly significant experiment?’ And it seemed to me that if, instead of having a group exerting pressure on judgments about lines, the group could somehow induce something more significant from the person, then that might be a step in giving a greater significance to the behaviour induced by the group. Could a group, I asked myself, induce a person to act with severity against another person?

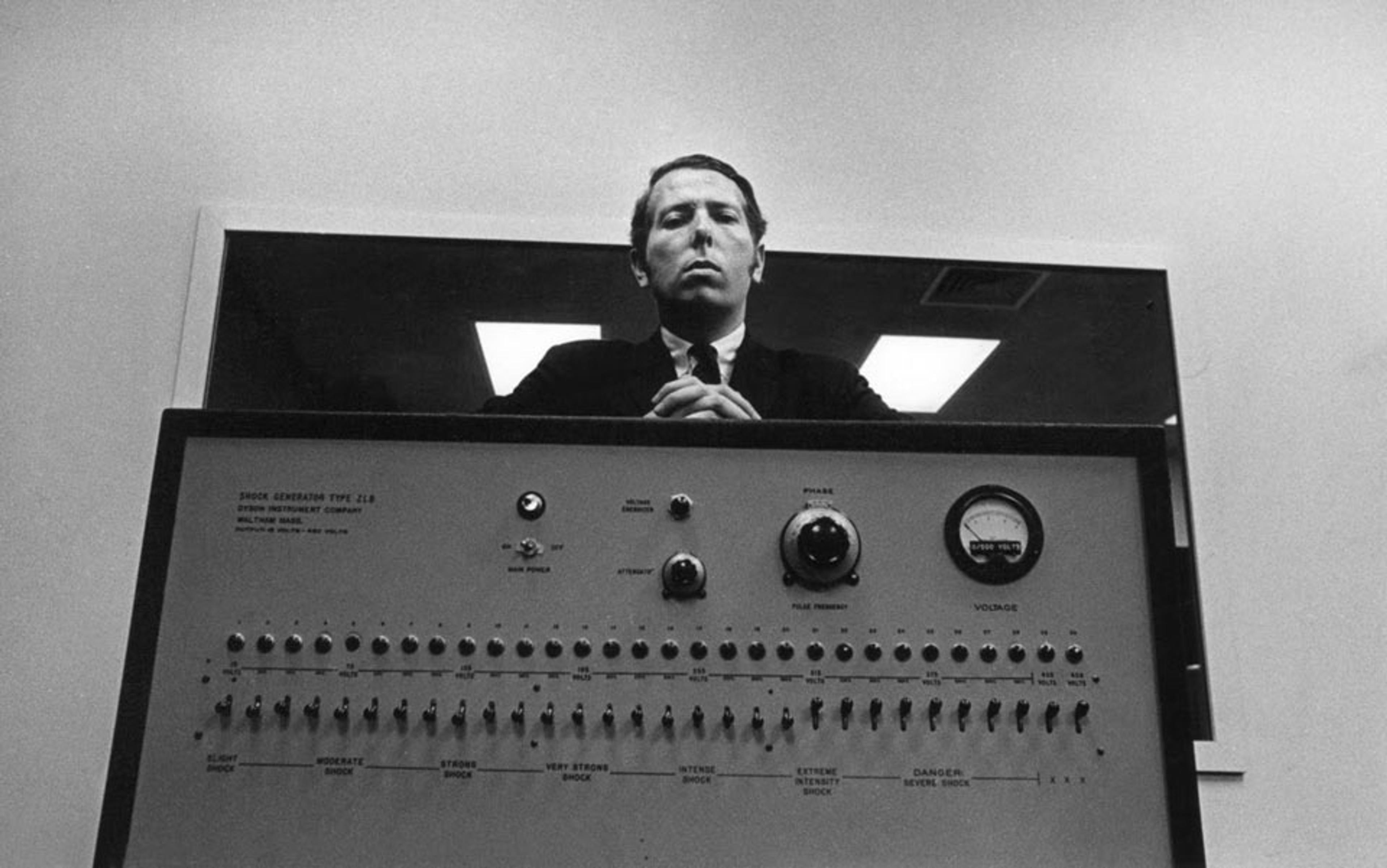

Milgram made sketches of a long box with circular buttons numbered one through nine. It was an electric shock indicator, a way to quantify and measure a person’s willingness to torture. This was the significant test he was looking for. No one would be actually shocked, of course, but the confederate would fake it. There was only one problem: in Asch’s experiment, it was easy to get a control test without group pressure; all you had to do was give the same line test to an isolated individual. But without the group, a lone person wouldn’t have any cause to shock a stranger. The control would require the experimenter to order the subject to perform.

In what he later called an ‘incandescent moment’, Milgram became more interested in the control than the test. He wondered how far people would go to follow his orders, and so he shifted the experiment’s focus from conformity to obedience. He planned to try it on Americans in New Haven, after which he would perform the experiment in Germany to see how the two compared. But once he saw the first results, Milgram knew the German comparison wouldn’t matter.

You probably already know the story: the subjects were far more obedient than they were expected to be, in both frequency and intensity. Milgram surveyed other psychologists before he ran the experiments, and his consulting group guessed about a tenth of one per cent (.125) of subjects (only sadists and psychopaths) would max out the voltage before refusing. Instead, 65 per cent of subjects hit the 450 volt button – labelled ‘XXX’ instead of ‘lethal’ in the final model – three times before Milgram cut them off. All subjects reached 300 volts, which meant they believed they had administered 20 distinct shocks. It was a successful experiment. Too successful. Cross-cultural comparisons were beside the point if most Americans were already Nazis just waiting for the right orders.

In his book Obedience to Authority (1974), Milgram published the results of his first experiment, along with the different variations he’d tried. It’s an ostensibly dry text, yet a narrative seeps through the columns of results and lists of control conditions. In the context of the first experiment’s unexpected results, the changed versions look like a man digging desperately for a limit. In the second test, he had the shocked confederate call out in pain and plead for mercy, clearly audible through the wall. A few more subjects stopped early, but only one person fewer went all the way. In the third test, Milgram put the victim in the same room as the shocker, but still 40 per cent got through 450 volts. Determined to find something humans wouldn’t do, the fourth version of Milgram’s experiment required the subject to hold down the confederate’s hand on a shock plate, even as he refused to co-operate and begged to be set free. Still, 12 of 40 subjects went all the way.

Milgram kept looking for ways to isolate the reason for this failure of empathy. He tried to establish a new baseline by having the confederate complain of a heart condition and scream as if he were actually dying. After 330 volts, the confederate would make no response, as though now unconscious or dead. It didn’t move the needle. ‘Probably there is nothing the victim can say that will uniformly generate disobedience,’ wrote Milgram. Begging for your life, it turns out, doesn’t do much good. Milgram could get subjects to rebel if he inserted disobedient confederates or a second authority with conflicting orders, but he never found a vaccine. In the epilogue of Obedience to Authority, he concludes that the human willingness to obey orders is ‘a fatal flaw nature has designed into us, and which in the long run gives our species only a modest chance of survival’. This had not been his hypothesis, nor was it his hope.

The spectre of Nazism and the banality of evil haunted the Milgram experiment. The capture and trial of the Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann took place at the same time as Milgram’s tests; the tests concluded within days of Eichmann’s execution. At the core of Milgram’s tests was the scientist’s desire to replicate as best he could the conditions of the gas chamber. He sought to induce the Holocaust in individual subjects so that he could measure evil at the atomic level. In an interview for 60 Minutes in 1979, Milgram told the host Morley Safer:

I would say, on the basis of having observed a thousand people in the experiment and having my own intuition shaped and informed by these experiments, that if a system of death camps were set up in the United States of the sort we had seen in Nazi Germany, one would be able to find sufficient personnel for these camps in any medium-sized American town.

It’s an ugly thing to know, and no doubt a stressful thing to prove a thousand times. After controversy regarding the ethics of his experiments, Milgram was denied tenure. He had a successful career at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, but nothing he did could eclipse the notorious experiment he had designed in his 20s. In 1984, Milgram died, after his fifth heart attack, at the age of 51.

When I first learnt about Milgram in a high-school psychology class, I asked my grandfather, a Jewish clinical psychologist of the same era, about the experiments. He shook his head, sighed, and said ‘Poor Stanley’. Milgram had hoped a version of the Nazis’ own racial logic could save the rest of us from being implicated in the depths of their crimes: that there might be some distinctive evil about the Germans. But once the cross-cultural comparison was quickly deemed irrelevant, why proceed with the experiments? As a society, what do we have to gain by recreating this historical trauma?

What Milgram and his assistants told the subjects was that they were doing important work to advance the cause of science. It wasn’t a lie per se, but the social value of this knowledge isn’t immediately clear. The conclusion that man is cruel and beastly is repeated throughout art, theology and philosophy, not to mention the historical record. Milgram half-heartedly hoped that knowledge and awareness about obedience might decrease the human propensity to follow orders, but there’s no evidence that this is the case. In 2007, the Santa Clara University psychologist Jerry M Burger in collaboration with ABC News reproduced the experiment under current ethical guidelines. Nearly half a century after Milgram first performed the test, they found virtually no change in compliance, even with additional warnings and disclosures to the participants. It’s one of the most famous social science experiments of all time, but awareness, like pleading, doesn’t seem to do much good.

And yet, despite there being no obvious social value and some obvious individual harm, researchers keep creating new Milgram experiments. In June, a group of European researchers released a Milgram-based study that cross-referenced participants’ shock scores (on a mock game show instead of a lab session) with their results from a personality survey administered months later. Though the results weren’t dramatic, they found that ‘nice’ and ‘agreeable’ people were more likely to follow instructions from a game-show host telling them to torture strangers.

He was haunted by the demon of obedience, of Eichmann and the gas chamber, and he took an active role in calling it forth

In 2005, a research team at Eindhoven University of Technology in The Netherlands produced a study that found a novel spin: they replaced the confederate/victim with a robot that participants had to train in word recognition. But with no sympathy for the bot, not one subject refused to obey. An international team of researchers had a similar idea in 2006 where they tried the experiment with a virtual confederate/victim. When faced with a life-size Sims-style cartoon figure, three of 20 participants disobeyed. The original Milgram experiment has also been repeated in a number of countries, including West Germany and South Africa. What all of these tests have shown is that, in a controlled situation, most people will obey an authority, even if that authority tells them to do something that conflicts with their morals; but why do research psychologists remain so interested in demonstrating the phenomenon?

Like the administrator in the experiment script, these researchers justify themselves with the pursuit of knowledge, but Milgram experiments seem to have a deeper motivation. In his essay ‘Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through’ (1914), Sigmund Freud introduced the idea of ‘repetition compulsion’. From the perspective of pleasure-seeking and pain-avoidance, Freud couldn’t understand why his patients would relive traumatic relationships from their past in therapy instead of trying to address them directly and move on. Gradually, Freud came to understand the urge to repeat as a way to master and control trauma, to take an active role in what had been a passive experience. The repetition that fills human lives ‘gives the impression of a pursuing fate, a daemonic trait in their destiny’, wrote Freud in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920).

Milgram was the child of two eastern-European Jews, and as an adolescent he was keenly aware that it was only historical chance that put him in New York and not a Nazi camp. His oft-cited letter to a Harvard classmate in 1958 reveals a young man beset with survivor’s guilt: ‘I should have been born into the German-speaking Jewish community of Prague in 1922 and died in a gas chamber some 20 years later,’ Milgram wrote. ‘How I came to be born in the Bronx Hospital I’ll never quite understand.’ He was haunted by the demon of obedience, of Eichmann and the gas chamber, and he took an active role in calling it forth from where it sits in the human psyche.

The Holocaust haunts more than just Milgram; in many ways, it’s the founding trauma for social psychology. So great was its influence, that in his 1979 history of the sub-discipline, Dorwin Cartwright wrote: ‘If I were required to name the one person who has had the greatest impact upon the field [of social psychology], it would have to be Adolf Hitler.’

Psychoanalysing the discipline itself helps to explain why social psychologists continue repeating the same series of experiments beyond their utility. The Jewish gestalt psychologist Kurt Lewin emigrated from Berlin to the US when Hitler came to power in 1933. Three years later, he would publish the founding equation of social psychology: B = f (P, E), meaning that behaviour is a function of a person in their environment. Perhaps the world expert on Milgram is Thomas Blass, a Hungarian Jew born during the Second World World War and himself a survivor of the genocide. So, far from being a pure, existential study of human nature, social psychology emerges from a particular moment in history.

Milgram didn’t write a hypothesis for an experiment, he made a script for a play. It’s poor science, but it might be great art

In Behind the Shock Machine (2012), the Australian journalist and psychologist Gina Perry assailed the very validity of the Milgram experiments. Although she initially came to the study of Milgram with sympathy for the haunted doctor, Perry quickly found a more worthy object for her feelings: Milgram’s subjects. Reviewing transcripts from the experiments in the Yale archive, she found a lot of disobedience hidden in the obedience numbers, and a number of confounding variables. For example, Milgram made sure subjects knew the payment for participation was theirs even if they walked away, but in the transcripts this seems to have triggered reciprocity with the experimenters. One subject continues only after the experimenter tells him he can’t return the money. Another obedient subject remonstrates after she’s finished obeying, because she quickly understands what the experiment was really about and is disgusted. In the drive for quantitative results, the procedure ignored valuable qualitative information. ‘I would never be able to read Obedience to Authority again without a sense of all the material that Milgram had left out,’ Perry writes, ‘the stories he had edited, and the people he had depicted unfairly.’

In an unpublished paper Perry found in the archive, Milgram was quite candid with regard to his experiment’s true purpose: ‘Let us stop trying to kid ourselves; what we are trying to understand is obedience of the Nazi guards in the prison camps, and that any other thing we may understand about obedience is pretty much of a windfall, an accidental bonus.’ Milgram didn’t write a hypothesis for an experiment, he made a script for a play. It’s poor science, Perry writes, but it might be great art.

To view the Milgram experiments as a work of art is to include the haunted young doctor as a character, and to question his reliability as a narrator. As an artwork, the experiments can tell us about much more than obedience to authority; they speak to memory, trauma, repetition, the foundations of post-war social thought, and the role of science in modernity. There is no experiment that can prove who we are but, in its particulars, art can speak in universals. Long after his tests are considered invalid, Milgram’s story will live on.