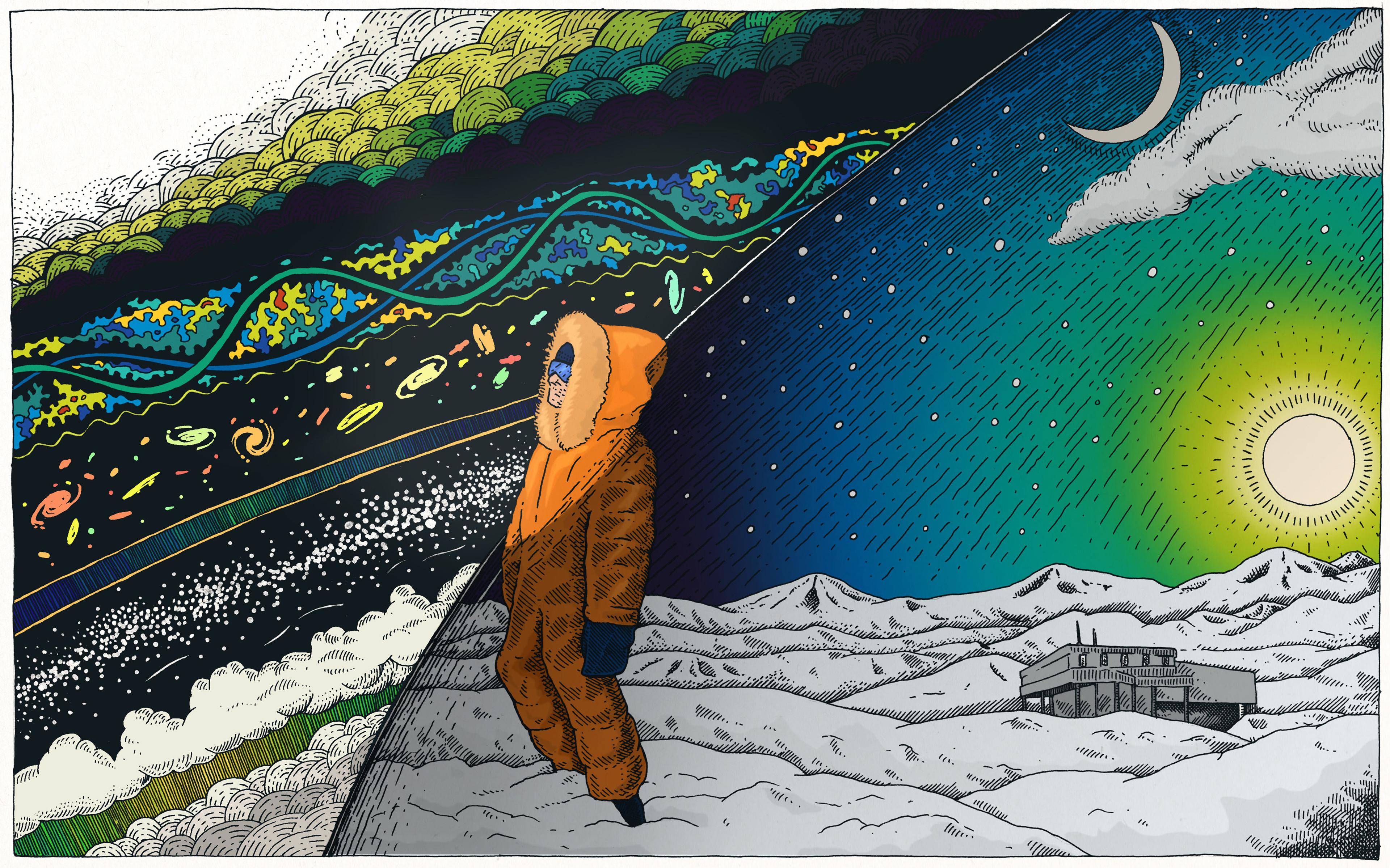

One afternoon some years ago, I was walking through the snow thinking about other universes. More specifically, I was turning over in my mind the fact that the hospitality provided by our universe depends on many extremely special things. For example, if the electric repulsion between protons in the nuclei of atoms were just a bit stronger, then those atoms, and hence chemistry, and hence life itself, could not apparently exist. And there are many other such ‘coincidences’. I had convinced myself that there were four – and pretty much only four – possible explanations for the fact that the laws of physics seem to be carefully chosen to allow us living, conscious beings to be here.

First, perhaps the laws of physics really were designed for us: when the universe began, it (or some superbeing that created it) had us – or at least life – in mind. Second, perhaps it was just an immense coincidence: there was one ‘roll of the dice’ that specified, among other things, the force between protons, and we just got colossally lucky. Third, it could be that many ‘universes’ exist with different laws of physics, and we are perforce in one of the universes that allow life. Fourth, perhaps the coincidences are illusory: perhaps life would somehow find a way to arise in any universe, with any possible set of physics.

A feeling grew in the pit of my stomach that the Universe really is a pretty mysterious place. The mystery is not about why the Universe has some particular properties rather than others, but about the connection between those properties and our very existence as living, conscious beings contemplating those properties. Not only are you intimately connected to the Universe on the largest scales, you are central. This is not to deny that you are in some sense an infinitesimal arrangement of dust on one small planet out of billions of trillions in our observable universe, which might well be one of many universes. But you are also a giant: a thinking, conscious being responsible for giving meaning, and even existence, to the universe you inhabit.

Sometime after, I was recounting my thoughts to a good friend who happens to be a longtime practitioner of Zen Buddhism. He noted that my experience reminded him of Zen koans, vignettes that embody teachings about reality as explored by Zen adepts. Through koans, a teacher can confront a student with a situation that, while initially baffling, can be resolved through added insight rather than more knowledge or previous experience.

I decided to create a set of cosmological koans to explore the connections between us and the Universe – a set of open doors through which you are invited to walk. The selection below interrogates the nature of time, and the way we pass through it in the cosmos at large.

Right now, as you read this, a baby in India is taking its first breath, and an old woman her last. A young woman and her love are sharing their first kiss. Lightning flashes across a dark sky. The wind blows through the hair of a solitary hiker in the Sahara desert.

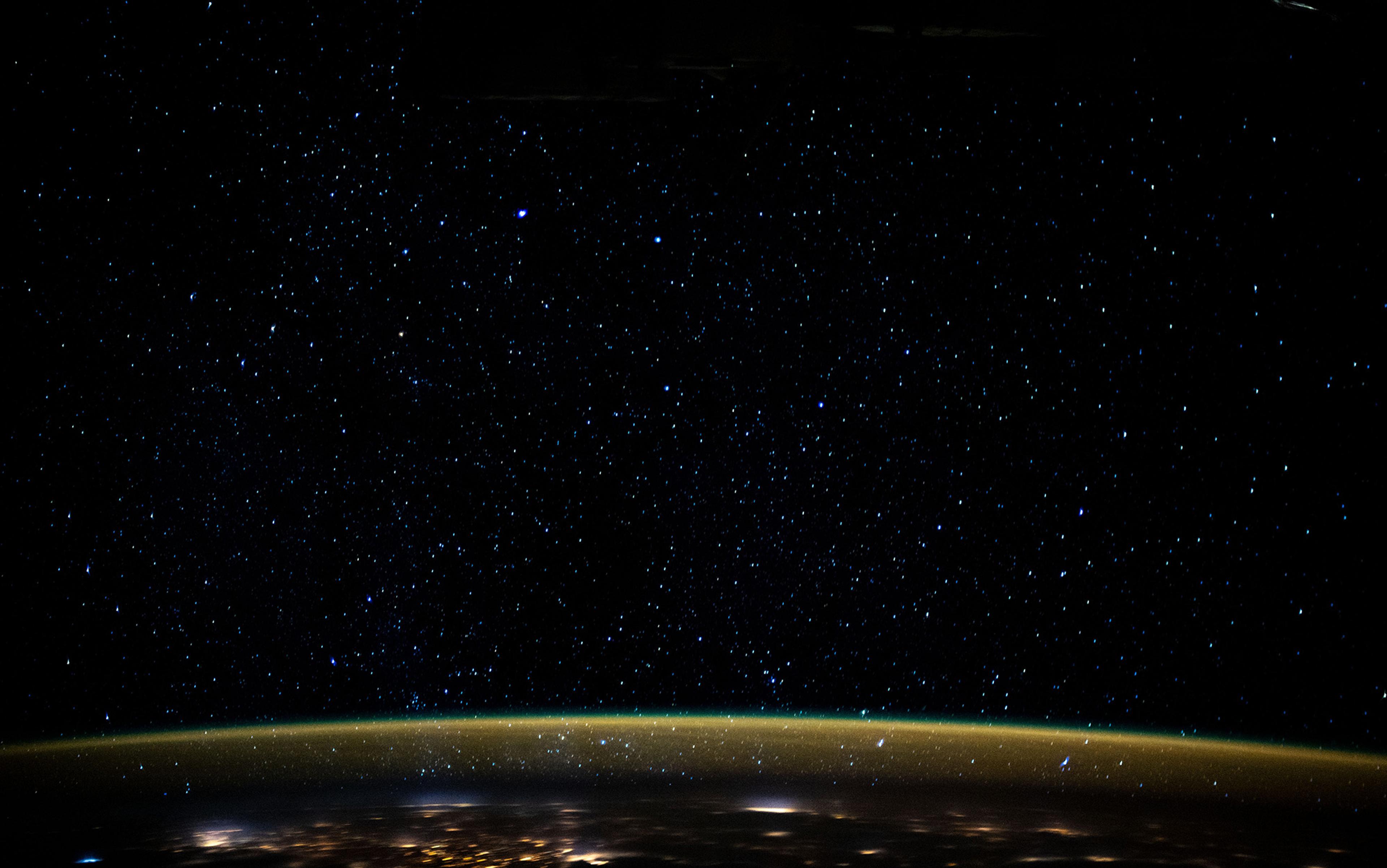

A satellite is seeing the Sun rise above the Earth. A hurricane is blowing endlessly through the clouds of Jupiter. Two rocks are colliding, just now, in the third ring of Saturn.

The new year is arriving on a planet around a star in our galaxy. Perhaps the world has inhabitants who are celebrating.

Our galaxy moves about 100 miles closer to our neighbour Andromeda, toward their collision and union 4.5 billion years from now.

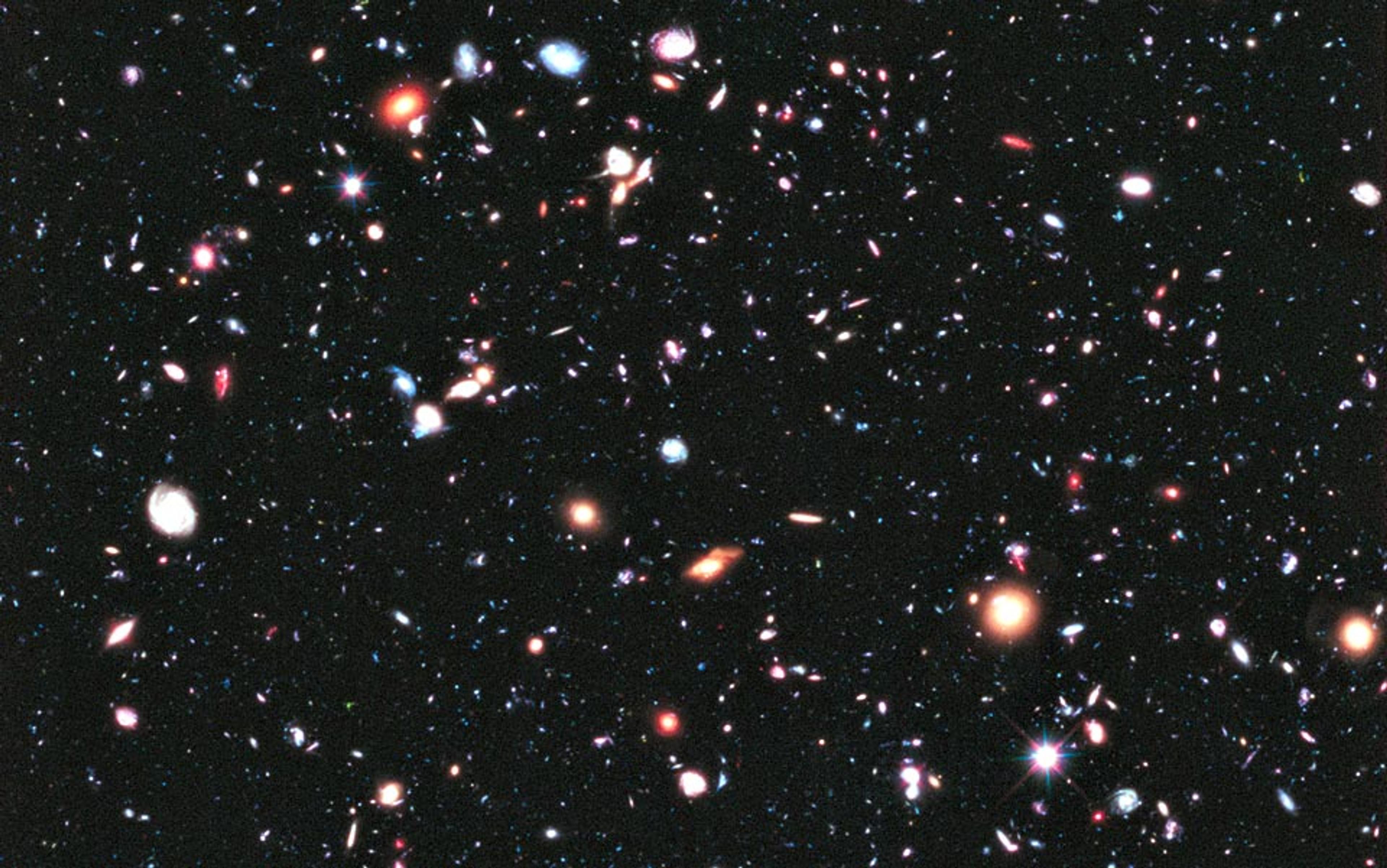

A star in a distant galaxy ignites a titanic supernova explosion that ends its 100-million-year life. At the same time, hundreds of new stars first ignite.

The observable universe adds enough new space for 100 new galaxies.

All of this is happening this very second, across the universe, right now.

Yet this ‘right now across the universe’ does not exist.

Did a child in India really just take its first breath? Probably. There are about a billion people in India. If each person lives up to 100 years, then at least 10 million people must be born each year just to maintain India’s population, and of course the population is growing. Now, a year has 365 days of 24 hours of 60 minutes of 60 seconds – or about 30 million seconds. Thus, on average, at least one person is born every three seconds in India. A more careful estimate shows that one person is born about every second there, so indeed it is likely that, in the last second, a baby there took its first breath.

The explosive death of a star occurs many times per second somewhere in the observable universe

What does this illustrate? First, that there are many interesting calculations that can be done approximately – but well enough – using just some thinking and some numbers that we might happen to know or can easily obtain. These are often called order of magnitude estimates. The art of these calculations is to understand the essential ingredients of a question, to know how to combine them, and to be able to obtain the result to within a factor of about 10 – that is, to be able to say that about one Indian child is born each second, and not 10 per second, or one per 10 seconds.

These numbers also illustrate how very large our world is. Birth – an event that happens just once in a person’s lifetime – happens every second somewhere in the world! Similarly, the explosive death of a star as a supernova, which happens just once in the 100-million-year lifetime of just a small fraction of stars, occurs many times per second somewhere in the observable universe. (I follow the convention that ‘Universe’ means roughly all that exists; ‘observable universe’ means that which we can currently probe using observations with telescopes and other experiments’, and ‘universe’ means the space-time region encompassing, and with similar properties to, the observable universe. Is the Universe bigger than the universe? Bet on it!)

It is a big place! (And getting bigger, to the tune of about 1062 cubic metres per second.)

When we contemplate all of these things happening now, it feels very intuitively clear what we mean by ‘now’: some event either happens now, or it does not, right?

Wrong.

To begin to see why, let’s think about what we mean when we say something is ‘happening now’, and in particular how we know it is happening now. When you say that a falling leaf hits the ground ‘now’, you mean that the event coincides with your internal perception of the present. When you say that the leaf hit 10 seconds ago, you mean that your internal ‘clock’ (or maybe a wristwatch) has ticked 10 seconds since your perception of the landing leaf.

But imagine yourself in the thunderstorm that is happening somewhere on Earth at this moment. You notice that a flash of lightning and the accompanying thunder happen at different times by your internal clock. The interpretation is simple: the thunder is a soundwave travelling at the speed of sound and takes some time to reach you; the flash, travelling at the vastly faster speed of light, takes an imperceptible amount of time. Just as for the falling leaf, this light-travel delay is so short that you generally consider the strike to happen at the same time that you see it.

On larger scales, however, the effects are quite noticeable and even dramatic. When commanding missions elsewhere in the solar system, space scientists have to contend with delays of minutes or hours between the occurrence of events and the arrival of the signals describing them. Looking at the night sky, you ponder stars as they were tens, hundreds, or even thousands of years ago. And when astronomers observe distant galaxies as they rush away from ours because of the cosmic expansion, they are looking back billions of years through cosmic history; not only were galaxies younger, but the universe itself was expanding at a different rate.

We can look even farther: the so-called cosmic microwave background radiation consists of light that has freely travelled to us from a time 13.8 billion years ago, when it last interacted with a hot stew of hydrogen and helium gas. This light gives us an image of the structure of the universe when it was newly formed; the eventual vast array of galaxies, planets and stars was still just an embryonic ripple in the cosmic sea. This view of our nascent universe is here with us, right now; a bit of the static on an untuned (nondigital) TV is this very radiation. In this sense, we are seeing the universe’s earliest epochs right now, just like the view of the falling leaf.

This commingling of the present and the most distant past makes it clear that there is a complex relationship, and there can be an enormous difference, between what is happening right now and what we are observing right now. This does not feel terribly troubling, but it is a good reason to be very cautious. In particular, it suggests that we pay heed only to things that happen at the same time and the same place (the same ‘event’). For example, perceiving a leaf ‘now’ means that the light is reaching our eyes at (very close to) the same time and place as our internal perception of ‘now’ is taking place; the actual impact of the leaf on the ground is a different event. Likewise, if you disconnected your analogue TV a few years ago and had your last peek at the cosmic dawn then, this event was quite different from the initial launch of that radiation from the early cosmic fireball.

At 5:10, though she did not know it, amazing things were happening on Mars ‘right now’

But so what? you might ask. Despite these facts about what we know of the universe right now, our intuition tells us that there is something like a big cosmic clock ticking away in the background, that depends neither on our perception nor on our knowledge of when events happened. As Isaac Newton put it: ‘Absolute, true, and mathematical time, of itself, and from its own nature flows equably without regard to anything external …’ That is, although we see the stars in a delayed sense, there is still some particular way that the stars are right now; we would just have to wait a while to find out. Underlying this intuition is the idea that we could have some sort of signal that travels as fast as we like and that, if we used that signal, we could see the stars as they truly shine at this very moment.

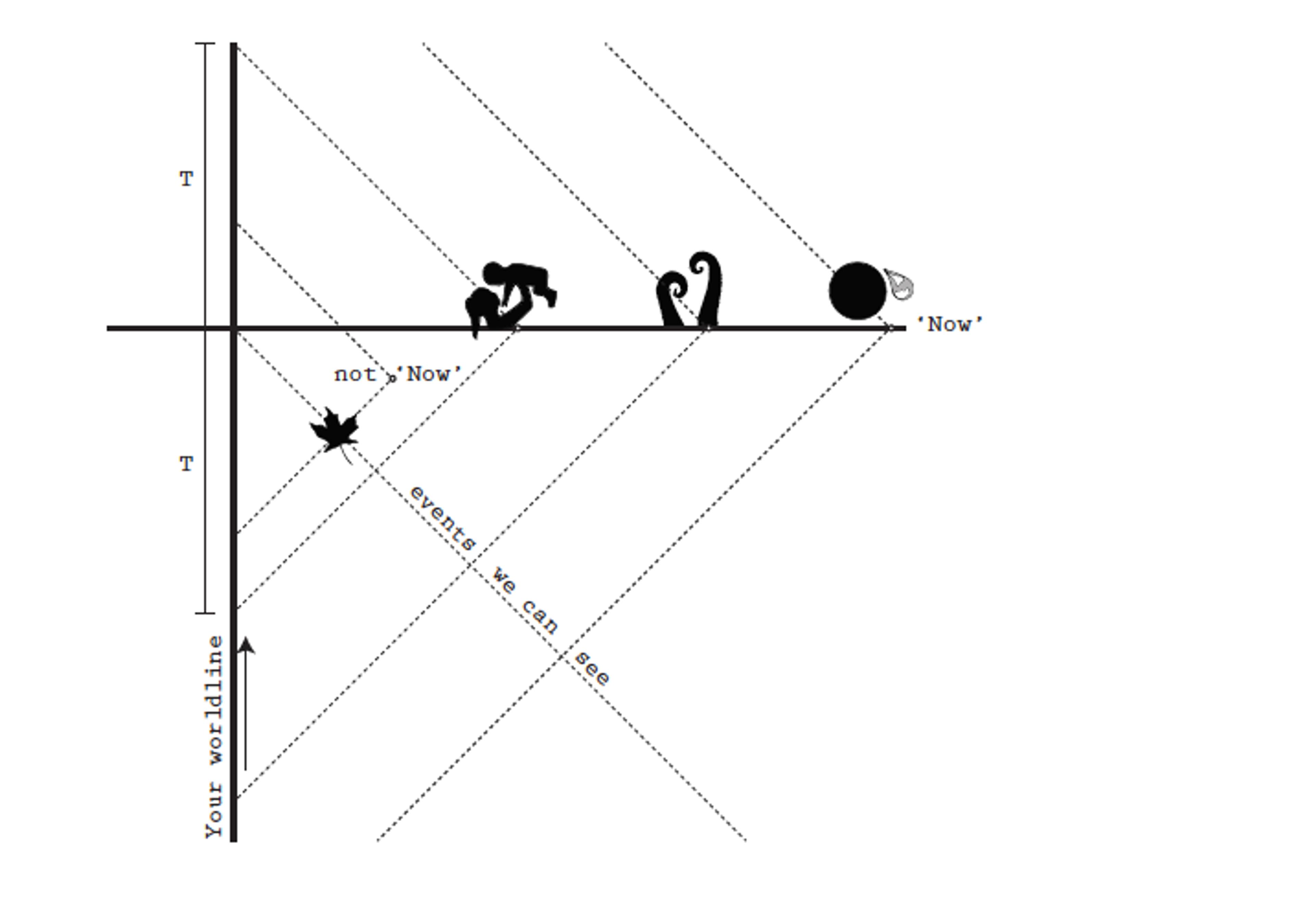

Even if no such signal exists, we can still imagine the set of events that happen right now, at least in retrospect, as it were. Suppose it is 5:00pm, and a NASA technician sends a signal to an exploratory vehicle on Mars, instructing it to take a photo and send it back. When, at 5:20pm, the technician receives a photo showing a waving tentacle about to grab the camera, she can infer that first contact occurred at 5:10pm. At 5:10, though she did not know it, amazing things were happening on Mars ‘right now’. Similarly, we could think of all sorts of events that are happening right now, by giving the corresponding definition, invented by Albert Einstein: if we sent a light signal to an event a time (t) ago, and if that signal reaches the event, turns around, and returns to us at exactly the same time (t) in the future, then we say that the event is happening now. Events for which this is not true would be in the future or the past.

The intersection of your worldline (vertical) and ‘now’ is here and now. From Cosmological Koans by the Anthony Aguirre

Taking this to its logical conclusion, by imagining signals all throughout the universe, we would think it possible to construct – in principle at least – the cosmic now. That is, we can imagine all sorts of events, all across the cosmos, even those that we cannot actually observe for a long time, if ever. And we feel quite strongly that each such event either is happening right now, or is not.

This construction is perfectly sensible, and accords with your intuition – but it is an illusion we maintain. Events such as the falling leaf or shining stars that we can see here and now are those from which light is reaching us now, and lie along the diagonal line labelled ‘events we can see’. Events such as the baby being born in India, the Martian waving its tentacles and a planet falling into a black hole are happening ‘now’, but not here; we cannot yet see them (we’ll have to wait a time (t), for example, to possibly see that the baby in India has been born). These ‘happening now’ events are defined to be those events for which we can imagine a light signal sent by us a time (t) ago that reaches the event, turns around, and returns to us exactly a time (t) from now. This is how we extend our sense of the cosmic ‘now’. Yet the universal now, the set of all events everywhere that are happening at the same moment as you read this – so clear in your mind – is just a dream.

This is an edited extract from ‘Cosmological Koans: A Journey to the Heart of Physical Reality’ (2019) by Anthony Aguirre, published by W W Norton & Company, Inc. and Allen Lane. Copyright 2019 Anthony Aguirre.