In the 18th century, European scholars began to envision a more enlightened world in harmony with nature. The old aristocratic regime, some hoped, would soon be replaced by a progressive society in which moral and social values were aligned with the natural and mechanical sciences. Aligning with nature, however, was not always a straightforward or positive process. In an enlightened world, human populations could not expand indefinitely. Resources would quickly become depleted by growing demand, which would slow progress and send humanity backward. That is why, at the end of the century, the British economist Thomas Malthus proposed that the growth of human populations needed to be kept in check. Like other species that were held in equilibrium with their environment, we should also find a balance between the supply of available resources and their demand. But if we failed to control our own populations, Malthus believed that war, famine or disease would do it for us. For humanity to advance, we needed hard limits.

Malthus’s ideas emerged at a time when Britain was being socially reconfigured. Rapid industrialisation and the expanding economy were followed by a population boom in which growing cities became overcrowded and dirty, leading to deteriorating living conditions. Poverty was on the rise, and social unrest grew as riots, strikes and protests spread across Britain. In 1843, Thomas Carlyle described England as ‘dying of inanition’ – a word that suggested the country was, despite its material abundance, starving to death from a lack of nourishment. The fabric of society seemed to be unravelling, the long-awaited enlightened world became a faraway dream.

A solution came from a naturalist inspired by Malthus’s vision. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection echoed the same idea: living organisms could not multiply infinitely, while resources were finite. Too few resources increased the pressure for survival, leaving only the ‘fittest’ to survive. But in the process of understanding ourselves as survivors, we lost our special status as divine creations. In 1867, the poet Matthew Arnold felt this loss when he described the spiritual emptiness created by evolution in terms of a retreating ocean heard only as a ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’. For Arnold, the fact that humans were part of an aimless natural process was a source of anguish. For others who were inspired by Darwin and Malthus, the problem was exactly the opposite: human societies had become unlike processes of the natural world. Medicine, social reform, benevolent people and institutions had relaxed the struggle for existence. The less fit no longer had to strive for their survival, which meant evolution had slowed. Even worse: society and nature seemed to collapse under the weight of the growing numbers of the ‘unfit’.

To Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton, this scenario was apocalyptic. Galton’s solution: human society had to take evolution into its own hands. In Hereditary Genius (1869), he wrote that social decline could be scientifically altered by applying Darwin’s laws of natural selection. Poverty and other social ills, he claimed, could be alleviated by selectively breeding more ‘endowed’ human beings, and slowing down the multiplication of the less fit. In 1883, Galton called his dream for new human possibilities ‘eugenics’.

Francis Galton by Charles Wellington Furse, 1903. Courtesy the NPG, London

Within several decades, however, Galton’s carefully crafted science of ‘improvement’ had begun to usher in some of humanity’s worst nightmares. In the early 20th century, eugenicists in the United States forcibly sterilised ‘feebleminded’ mentally ill people as well as ‘inferior’ Native American Women. And in Nazi Germany, the racial underpinnings of eugenics would soon lead to the unthinkable: the orchestrated deaths of millions. Recall the words of the German professor of medicine and Nazi party member Eugen Fischer who said in 1939: ‘I reject Jewry with every means in my power, and without reserve, in order to preserve the hereditary endowment of my people.’ For Fischer and other Nazis, ‘every means’ included genocide.

As the horrors of the concentration camps came to light, those who had advocated for utopian human possibilities through eugenics suddenly seemed naive. Galton and others appeared, at best, horribly misguided. Criticism of the Nazis’ racial hygiene project ran high immediately after the Second World War, with many equating eugenics itself with the Holocaust. Not only were the Nazis condemned, but the word ‘eugenics’ was, too. It was, as the American historian Nancy L Stepan wrote in 1991, eventually ‘purged from the vocabulary of science and public debate’.

In response to the devastation of the war, including the catastrophic outcomes of racial science, global efforts were made to establish a new humanitarian vision for Earth’s future. And central to this vision was the founding, in 1945, of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). From the beginning, UNESCO aimed to overcome the ignorance and prejudice that contributed to the Second World War. The agency’s founders sought to promote cosmopolitanism and interculturalism to ameliorate fraying international relations. UNESCO, they hoped, would become a beacon of peace, cooperation and human dignity. The only problem? The man hired to direct the fledgling institution was a eugenicist.

Julian Sorell Huxley was born in London in 1887, the eldest son of Julia Arnold, an educator, and Leonard Huxley, a noted writer. Julia came from a family of authors – she was the niece of the poet Matthew Arnold – while Leonard was the son of Thomas Henry Huxley, a famed zoologist who had been dubbed ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ and ‘Evolution’s High Priest’ for his advocacy of natural selection. Julian and his brother Aldous Huxley, who would later write the novel Brave New World (1932), inherited their family’s love of both the Classics and biology. Their grandfather’s fame, however, did not translate into great wealth for the family. They were, by the day’s standards, middle class, affording a governess-companion to look after their children, but sending those children to university was a real financial challenge. Julia and Leonard were thus anxious that their children should get scholarships. Julian eventually won his way into Eton and Oxford, which instilled in him a view (expressed much later, in 1970), that children should receive financial help to study only if they are gifted. Just as it had been for Malthus and Galton, Huxley’s middle-class sentiments meant that he believed nature and nurture should be balanced.

At Oxford, where he studied between 1906 to 1909, Julian chose to study zoology, but that was by no means a straightforward decision – with his mother’s encouragement, he had seriously considered studying Classics. While at Oxford, the young Huxley was taught by the embryologist J W Jenkinson, who had completed a degree in Classics before taking up zoology. And it was partly Jenkinson who infected Huxley with a passion for broad philosophical questions about life, including how the seemingly immaterial mind could be explained through material biology, and whether life had an aim. These were questions that Huxley pursued in his early writings, such as The Individual in the Animal Kingdom (1912) and Essays of a Biologist (1923). Huxley’s broad interests and his writer’s talent at presenting complex ideas took him far, intellectually and professionally.

They pleaded for science to be included in the institution, which was initially to be baptised ‘UNECO’, without the ‘S’ of science

It is hard to say when he was first drawn to eugenics. He was likely inspired by his Oxford tutor Geoffrey Smith, a zoologist who also wrote on the idea of improving humanity, and influenced by his friend Alexander Carr-Saunders, a eugenicist who had written books on Malthusian topics and on eugenics. It is also likely that during Huxley’s time at Oxford he may have absorbed the well-established idea of the ‘Oxford man’ – a supposedly highly educated and genetically endowed person.

Eugenics, however, was just one of the many interests he pursued in his early years. In 1923, Huxley became a founder of the British Journal of Experimental Biology and, later, of a thinktank called Political and Economic Planning, which was tasked with anticipating future societal changes based on science. In 1935, Huxley even became the secretary of the Zoological Society of London, endeavouring to make general biology accessible to all.

His entry into the world of UNESCO began in 1944 when he attended a meeting of the International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation. This advisory group for the League of Nations was about to be replaced by a new UN agency concerned with education and culture. Huxley attended the meeting to plead, along with others, for science to be included in the institution, which was initially to be baptised ‘UNECO’, without the ‘S’ of science. He would soon become more involved. When the institution’s first proposed director had to be replaced, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Education, Sir John Maud, chose Huxley as a replacement. In 1946, he became the first director of UNESCO. Maud believed Huxley would be a great fit, as he had the experience and the capacity to engage with the broader questions of life. Less certain, however, was how Huxley’s ideas about eugenics would fit with UNESCO’s vision for a new world.

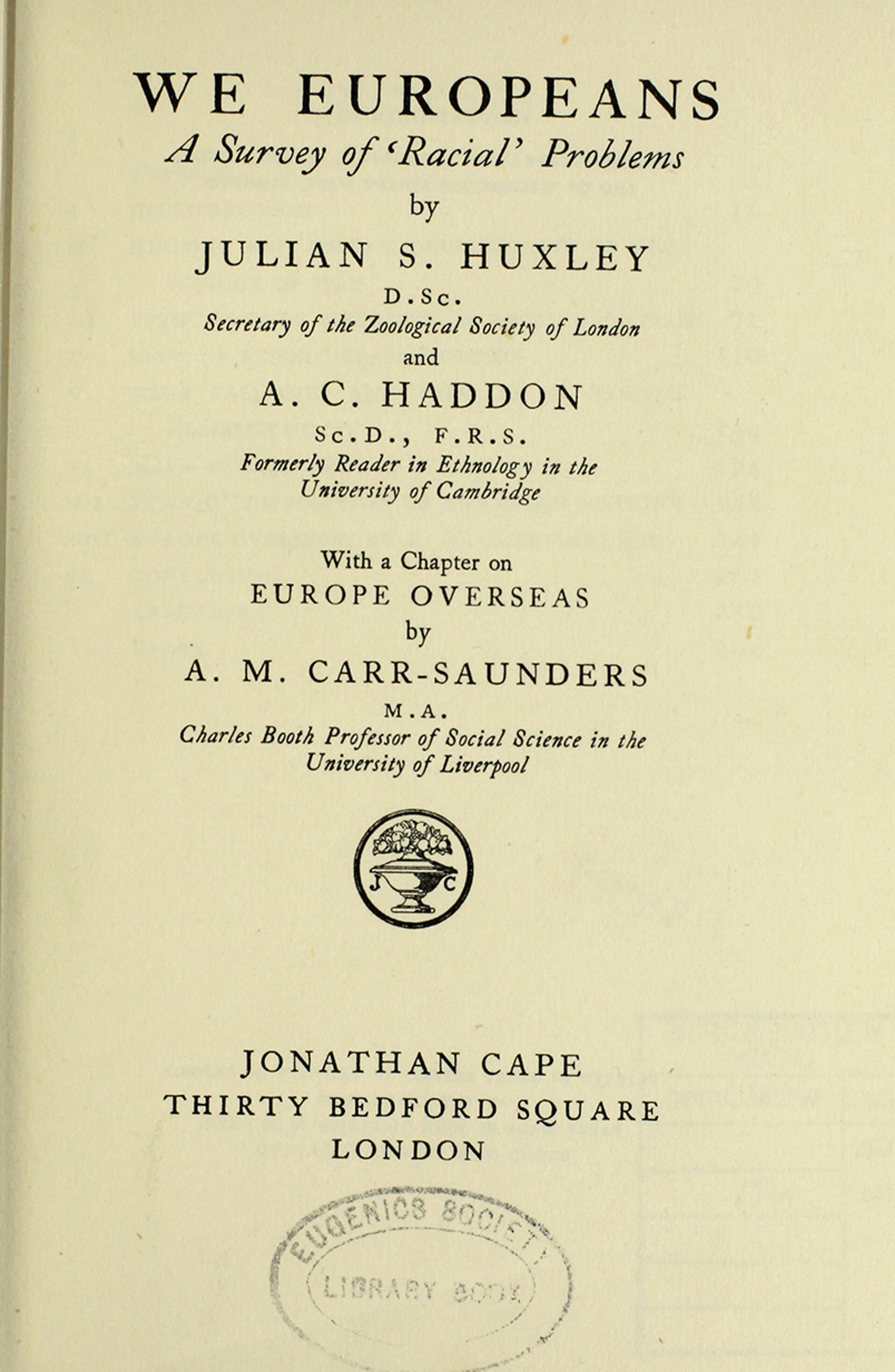

Today, we tend to think of eugenics as a Nazi catastrophe of racial cleansing. But, for Huxley, racial cleansing and human evolution were distinct. In a co-authored book, We Europeans (1935), Huxley campaigned against the racism of fascists and other nationalists, especially the eugenics of Nazi Germany. Though he was a eugenicist, Huxley did not see himself as a racist. Discoveries in genetics and statistics proved to him that there were more individual differences within racial groups than racial differences between groups.

Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

Huxley’s ideas show that, in many ways, our modern understanding of eugenics is overly simplistic. According to the American historian Diane B Paul in Controlling Human Heredity (1995), eugenics ‘was a more diverse movement’ throughout its existence. At some points, radical eugenic policies like forced sterilisation were carried out; at other times, eugenicists in Western nations tried strategies that were more similar to those used by welfare states. Almost all Western countries engaged in multiple forms of ‘improvement’. In Europe, eugenicists often tried strategies that were closer to those used by welfare states than by Nazi Germany. These approaches involved genetic counselling instead of sterilisation and giving money to ‘genetically endowed’ couples so that they could have families. In Britain, eugenics meant many things to many people, and Huxley’s eugenical vision for UNESCO was more nuanced than we might first assume. If we hope to understand his ideas, we need to resist the impulse to immediately equate them with the horrors of Nazi Germany.

Huxley’s vision for UNESCO was rooted in a specific view of evolution, which did not emerge fully formed. His ideas were a product of his heritage and experiences during the first decade of the 20th century, as the Victorian era gave way to a new age. This was a time of intense debates about progress and evolution.

Our success at surviving and reproducing had become a threat to our future success as a species

One key figure who was cited in these debates was the English philosopher Herbert Spencer who, decades earlier in the 1870s, had taught that human societies could be understood as natural products of evolution. According to Spencer, competition filtered the best and encouraged evolution, but this did not mean that one individual had to compete with another. He argued that individuals often had better chances of survival if they banded together in groups to outcompete rivals. The best could emerge if the individuals who cooperated were gifted enough to make the cooperation work. This aspect of cooperation was mostly lost on contemporaries, who were taken aback by Spencer’s emphasis on competition and the natural struggle for survival.

Julian’s grandfather felt differently. Thomas Henry Huxley may have been Spencer’s friend, but he could not stomach the philosopher’s emphasis on the struggle for existence in society. Thomas believed that the competition seen in nature should not serve as a guide for human behaviour. Reeling from the premature death of his daughter, he doubted whether nature truly selected out the best. And he made this clear during an impassioned lecture at the University of Oxford in 1893, which also served as a carefully crafted response to Spencer’s ideas: ‘Let us understand, once and for all that the ethical progress of society depends, not on imitating the cosmic process [including the struggle for existence], still less in running away from it, but in combating it.’ Rather than replicating the sometimes violent competition seen in nature, Thomas believed society ‘requires that the individual shall not merely respect, but shall help his fellows.’

The problem was that, by limiting natural selection in human society, the blade that once cut down out-of-control populations would become dull, and human progress risked slowing or reversing. Other species lived and died according to the limits of their environments. Humans seemed to flourish without limit. Our success at surviving and reproducing, facilitated by the lack of natural selection in society, had become a threat to our future success as a species.

Though overpopulation was a problem that Thomas believed could be partly tackled by competition, he was reluctant to turn to eugenics for answers for fear of suggesting that natural selection would damage our advanced ethical instincts. Instead, he tried to appeal to human morals – responsibility towards society – to cut down on reproduction. But what was human morality to be based on if not the Bible or nature? The answer to that question would eventually come from his grandson Julian.

Julian Huxley’s solution involved understanding nature differently. The nature that would inform society’s morality and behaviour was not necessarily competitive. It was cooperative, highly coordinated, and harmonious.

This idea was inspired by the philosopher Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution (1907), a book suggesting that life was not just a linear progression of survival and adaptation but an ongoing, dynamic process. To Bergson, evolution was a tendency of increasingly greater complexification in which organisms gradually acquired more ‘parts’ or joined with other organisms to create a more complex lifeform. The parts inside the bodies of algae pale in comparison with those of a human being, with its myriad systems, organs and neurochemicals. To Bergson, an organism with more parts had a greater arsenal of strategies to adapt to its environment, which made it less limited. A very simple organism, capable only of photosynthesis, risked death when sunlight shifted away. However, a colony of simple organisms joined together had more options. In a group, one organism could specialise in photosynthesis, another in locomotion, like workers dividing their labour. In principle, a human eye was no different: some cells specialise in adjusting the lens, some become eye-muscles, some become optic nerves. For Bergson, complexity was the evolutionary process of simpler organisms coming together in an entirely new organic system, which had more flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances.

Huxley believed that what was true for simple organisms and the eye was also true for culture. In an essay called ‘The Idea of Progress’ (1917), he wrote that this process of coordination – the ‘increased harmony of parts’ – was a primary evolutionary trend. He believed that humanity could progress if human beings became culturally and biologically integrated into a harmonious society where each individual could live with their own special cultural background and biological endowment, as long as these did not damage the whole.

As the Nazi party grew more powerful in Germany, Huxley criticised the idea of a so-called Aryan race

Harmony was a key concept for Huxley. While deployed in Italy during the First World War, he contemplated just how unharmonious human societies were. It was during this time that he heard the news about the League of Nations, and thought it was a great alternative to warmongering nationalisms. But he wanted to take this alternative vision for harmony, integration and human progress even further. In his book Religion without Revelation (1927), Huxley argued that science could create greater harmony in society by giving humanity a common vision of the future, based on our shared evolutionary past. He called this endeavour to use science for human progress ‘scientific humanism’.This would become central to his project of eugenics at UNESCO.

In the 1930s, as the Nazi party grew more powerful in Germany, and its claims about racial purity spread, Huxley criticised the idea of a so-called Aryan race. In We Europeans (1935), he described this idea as a biological veil for a political agenda. At home in Britain, things were no better: genetics was often used to reinforce the class system and political power. Despite these issues, Huxley did not give up on eugenics.

His version looked different to people in Germany or in Britain. Huxley came to believe that equalising the economic and social environment – by distributing wealth, for example – fostered people who were truly biologically endowed. Under ideal conditions, these physically superior people could finally reach their full potential. ‘Under our social system,’ he claimed in the 1936 Galton Lecture to the Eugenics Society, ‘the full stature or physique of the very large majority of the people is not allowed to express itself.’ Instead, ‘innate high ability is encouraged or utilised only with extreme inadequacy.’ Only by harmonising the environment with human nature would the truly eugenically endowed emerge and flourish. Huxley believed that eugenics would be the best way of encouraging heightened abilities not just among living individuals, but across humanity’s entire future. What was less clear was what exactly defined a so-called heightened ability. What determined success?

One year after his 1936 lecture, Huxley became the vice-president of the Eugenics Society in Britain and held the position until 1944. This shows that, even while Nazi Germany was casting a shadow over eugenics, Huxley still believed in the goal of successfully fostering superior ‘endowed’ people. For Huxley, success was based on a conception of biological coordination. As he understood it, evolution expressed itself through incremental harmony.

In some people, the parts – the genes – of one’s heredity were more harmonised. In others, for one reason or another, these parts were less well integrated, leading to disease or other problems. Huxley’s references to a ‘gene-complex’ and ‘genic balance’ make it clear he thought of genetics in terms of integration and harmony. Those with more harmonised genes emerged when the social environment was itself harmonised, without political manipulation, war or overpopulation. And by the time he was appointed director of UNESCO in 1946, these evolutionary ideas had become much clearer to him. They would form the framework of his eugenical vision for the agency.

UNESCO was founded to encourage internationalism and cosmopolitanism. In 1946, Huxley quickly wrote a pamphlet that claimed to explain the institution’s underlying philosophy. He formulated three aims for UNESCO. First, continuing the evolutionary process of increasing harmony. Second, making all environments equal (harmonising them) and thereby revealing those who were less genetically endowed and unable to reach their full potential, even when they experienced the same economic and social conditions. Third, educating people about the underlying inequality of humankind, and the need to equalise environments.

In an earlier text, Religion without Revelation (1927), Huxley had defended his ‘scientific humanism’. But at UNESCO, he took this idea even further. The new agency would be based on a ‘scientific world humanism’, allowing humanity to progress through science and control over the natural world.

Cosmopolitanism in Huxley’s UNESCO was to be based on biological processes – on the increasing harmony between parts – not on older ideas of world citizenship developed by the League of Nations after it was founded in the 1920s. To the new director, these processes were how humankind would access the next stage of evolution.

In the 1946 pamphlet, Huxley reimagined the evolutionary process, giving it three distinct phases – an idea he would explore more fully in his book Evolutionary Humanism (1954). The first phase was inorganic, also called the ‘cosmological phase’. It involved elementary physical and chemical interactions that produced planets, stars and solar systems. The second phase was biological, in which inorganic matter gradually began to self-organise and self-reproduce faster, producing a higher level of complexity and organisation. Indeed, with every phase, the rhythm of change increased, as greater organisation gave organisms an increased ability to survive and reproduce, pressuring competitors to become better or perish. In the third and final phase, which Huxley called ‘psychosocial’, the mind organised the world through culture and traditions, giving rise to ‘cultural evolution based on cumulative experience’ or ‘cumulative tradition’. Through the mind – through language, concepts, culture – evolution accelerated like never before. Like living matter, culture was engaged in a process of greater and greater integration. As Huxley explained to a journalist in 1946:

Man must find a new belief in himself, and the only basis for such a belief lies in his vision of world society as an organic whole, in which rights and duties of men are balanced deliberately, as they are among the cells of the body … By working together, we must lay a conscious basis for a new world order, the next step in our human evolution.

Harmonious cooperation was the means to this end. But, as the 20th century had shown, war and nationalism were direct obstacles to greater cultural integration. Another obstacle, Huxley believed, was increasing population numbers. Just as prejudice based on class or race led to the unequal distribution of resources, overpopulation would create limited resources, as Malthus had taught. An overexploited environment would produce infighting over whatever little was left. Thanks to medical advances, overpopulation also meant that people with various diseases and ‘bad’ genes were now surviving longer and reproducing more. An overabundance of people could lead only to less harmony. And so, as director of UNESCO, one of Huxley’s targets was reproduction.

This eugenical vision was rooted in Huxley’s view of evolution as a process of harmony and progress

In his 1946 pamphlet, Huxley tasked the agency with promoting scientific knowledge about the dangers of over-reproducing and encouraging the use of proposed ‘birth-control facilities’. These facilities would offer genetic counselling to people, helping them decide whether to have fewer children or none at all. Huxley hoped that these interventions would slow the rise in population numbers and teach people about new techniques such as artificial insemination, surrogacy and the preservation of ‘deep-frozen gametes’. In this way, humanity’s genetic complexity might be harmonised, leading toward a total harmonisation of life.

Huxley also set his sights on intelligence. Further human progress would be generated by fostering an increasing number of intelligent people. Based on the idea that two intelligent parents had an increased chance of having smarter children, Huxley believed that the average level of intelligence could increase if more people of higher intelligence could be born. Huxley recalled that most people in his day had an average IQ of 100, while ‘geniuses’ were at around 160. But if the average were raised to 120, for example, the frequency of those with 160 might also rise, and the possibility of those with 180, or even 200, would likely increase, too. This eugenical vision was rooted in Huxley’s view of evolution as a process of incremental harmony and progress. To create a new evolved world of superior intelligence, scientific world humanism involved discouraging those who were less ‘endowed’ from reproducing. The greater the average intelligence, the better the world-mind.

Huxley’s views, however, were immediately challenged. In 1946, UNESCO was still in embryonic form while it was being developed by a Preparatory Commission. This ultimately meant that his pamphlet had been published before it had been officially debated. Once it was clear what Huxley was proposing, the document was rejected by the Commission and branded as a representation of the director’s personal views. In a postwar world, few could publicly stomach Huxley’s vision of scientific world humanism.

At the time, UNESCO was also under pressure to preserve Christian principles in education. The Christian historian Sir Ernest Barker, who was a member of the Commission, swiftly protested what he thought was, as Huxley recalled, an ‘atheist attitude’. Huxley’s encouragement for birth control also displeased some on the Commission. Many of the countries that were to become part of UNESCO were still Catholic or of other religious affiliations, and found Huxley’s evolutionary justifications and support for birth control repulsive. Reciprocally, Huxley clearly had no liking for the established Church. He later wrote that ‘over-population was aggravated by the opposition of the Roman Catholic Church to what they called “unnatural” (ie, deliberate) birth-control’. In response, Huxley was forced to adopt a less overt approach. But there is no doubt that in his mind UNESCO would one day address the world’s problems by pushing more directly for birth control.

Under his direction, UNESCO was to be an evolved brain leading a harmonious international order against prejudices, nationalistic narrowness and overpopulation. It would do this through eugenics, by squeezing out bad evolutionary combinations of genes, by making steps in the evolutionary process of incremental biological and increasing psychosocial harmony. But Huxley’s views were not harmonious with the Committee’s vision for UNESCO. Criticised by members of the agency and others, the evolutionary process he wanted to harness had to be temporarily directed with smaller – and less disturbing – steps.

Huxley’s tenure as the first director of UNESCO was challenged from the very beginning. The US did not support him, partly because Huxley had visited the USSR twice before his appointment, and was outspoken about ‘cooperation’, which meant US officials smelled the red threat on him. In the end, the US did vote for Huxley’s appointment, but on the condition that he served for two years instead of the normal six. During that time, he tempered his writing on eugenics, but it would be a mistake to view this as a withdrawal from his grand vision for humanity.

Huxley didn’t just settle for promoting education, fighting poverty and publicising the dangers of overpopulation, as Malthus and Galton had done. For Huxley, UNESCO was part of a much broader evolutionary vision aimed at increasing harmonisation between members of a world society and with nature. He envisioned global interculturalism, cosmopolitanism and world coordination. Just as cells in the body functioned better when coordinated by a brain, Huxley thought that world cultures could be better interconnected and harmonised by UNESCO. This coordination was not a short-term project. Even if birth control and eugenics were unpalatable in the mid-20th century, Huxley believed a time would come when more educated people would become aware of their advantages. For Huxley, eugenics was always future-oriented. After his talk to the Eugenics Society in 1936, one review in the journal Nature claimed that his views on eugenics were ‘destined to become part of the religion of the future, or of whatever complex of sentiments which may then take the place of organised religion.’

It would also be an error to think Huxley’s views are outdated. After all, UNESCO still strives to equalise the environment by addressing poverty and education. And, in many parts of the world, aspects of Huxley’s version of eugenics live on. Fetal diagnoses are still performed, and, upon seeing a fetus ‘unfit’, some might perform a legal abortion. In vitro fertilisation, a dream of Huxley’s, now allows some people to select the semen, eggs and embryos more likely to produce genetically superior children. We may baulk at any talk of eugenics, or think of Huxley as naive for his view of scientific world humanism. Yet many of us make decisions related to genetics or reproduction that Huxley would likely have agreed with.

As historians have realised, ‘eugenics’ now usually happens through individual choices, not the guidance of a central brain. For that reason, most of us do not think of our personal choices as cobblestones in the road of evolutionary progress and harmonisation – a road that was, at one time, planned and designed by UNESCO’s first director.