Shortly after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, a friend forwarded me a post from an obscure email list. The writer had calculated that the continued existence of Afghanistan would delay the Rapture by six months. Millions around the world who would have had a chance of eternal bliss would be irretrievably lost to natural deaths in the interim. According to strict utilitarian reckoning, exterminating the Afghans via a nuclear carpet-bombing campaign would be the kinder course.

This heinous calculus didn’t come from the email list of some apocalyptic cult but from the ‘extropians’, advocates of a massive technological upgrade in the human condition. The event in question wasn’t in fact the Rapture but the Singularity: a predicted moment when the speed of technological advance would go off the scale and, in passing, let us abolish ageing, disease, poverty, and death. For extropians and other adherents to the doctrines of transhumanism, the human condition has been, in principle, a solved problem since 1953, when Watson and Crick published the structure of DNA. The rest is engineering.

For science fiction writers, of course, this is catnip. I first encountered transhumanism through the extropians, and exploited their ideas so enthusiastically that I’ve been counted among them myself. It was an extropian who first sarcastically defined the Singularity as ‘the Rapture of the nerds’, and I had a character use a variant of the phrase in my book The Cassini Division (1999). If you ask the internet, you’ll find the original endlessly attributed to me — which tells us something, but I’m not sure what.

In his book Humanity 2.0 (2011), Steve Fuller, professor of sociology at the University of Warwick, uses transhumanist themes to make a challenging point about humanism. He argues that Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theology, along with most Western philosophy, held that there was a human essence. Indeed, all species were defined by their essences, an idea that goes back to Aristotle. The idea that species might change was (almost literally) unthinkable: essences were thought to be as abstract and eternal as numbers. Darwin dissolved all such essences into populations, each of which had no intrinsic limit to variation. Philosophers of biology have long recognised that the shift from essentialist thinking to ‘population thinking’ was crucial to the modern understanding of evolution a point first fully articulatued by Ernst Mayr.

But once ‘humanity’ becomes a variant set of populations rather than an invariant essence, it loses its obviousness as a standard of value. The category becomes fuzzy at the edges: some parts of the population can be written out of humanity altogether; some superhuman (but still natural) entity, such as Nietzsche’s Übermensch or the extropians’ imagined transcendent future selves, might be seen as worth sacrificing present humans for. Alternatively nonhuman beings could come to seem as morally significant as humans, as is argued by animal rights advocates.

If you throw in the possibility of human enhancement — increased intelligence and longer healthy life spans — it can only exacerbate the situation. Fuller argues that many people are already moving beyond the ‘human baseline’, through online life and smart drugs. New and foreseeable technological and cultural developments make the boundaries of human and non-human even fuzzier, and possible distinctions (in intelligence, life span, health, abilities) within the human population even sharper. The principles of the welfare state, Fuller suggests, might be widely enough accepted to give us a basis for moral and political discussion, action, and eventual agreement on these questions. He argues that we should embrace the prospect of becoming Humanity 2.0, and bring it within democratic politics. The problem, as Fuller well recognises, is constituting a ‘we’ who can do that.

And so it becomes harder to imagine humanity as a unified body, able to shape a shared project around a common interest. Perhaps the time for such visions is already over. Since monotheism’s hold on grand theories declined in the ‘West’ the most ambitious, secular political movement to attempt to frame one was socialism, particularly in its Marxist form. It did this in two ways: theoretical and practical.

Theoretically, Marxism came up with a secular, materialist account of what made humanity distinctive: a complex, evolving, and indefinitely extendable interaction of labour, consciousness, and social relations, all rooted in the mutually reinforcing co-development of hand, brain, and tongue. This account did not depend on philosophical notions of human essence, so it was able to withstand Darwinian dissolution. From its speculative beginnings in the 1840s, Marxist theory had incorporated (necessarily hazy) evolutionary assumptions and of course was an historicist account of the human condition. It went on to welcome and include Darwin’s work: see, for example, Friedrich Engels’s influential fragment ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ (1876), in which the philosophical anthropology of Engels’s youth is recast as a Darwinian story of human origins — one that palaeontology was later to confirm.

A less happy consequence of the end of socialism as a mass ideology is the end of humanity as an imagined community

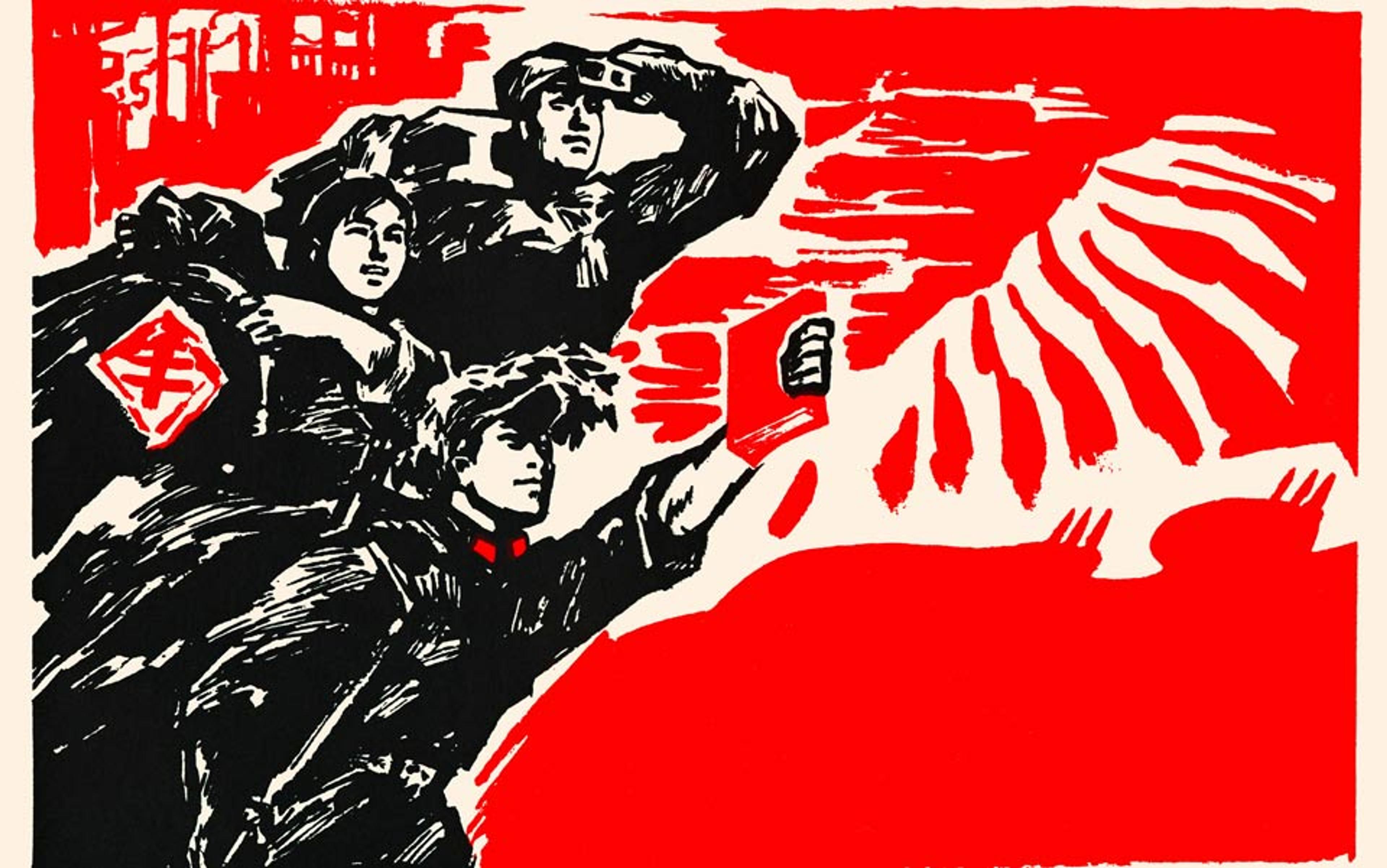

Practically, socialism (in both its communist and social democratic forms) set out to construct a common political project for the claimed ultimate benefit of all humanity. Particularly in its communist variant, this project sought to include not only the working class of the West but also hundreds of millions in the then-colonial world as part of a collective political subject (what the left-wing anthem celebrates as ‘the Internationale’). Marxist socialism acted in the name of a future in which, as the anthem has it, ‘the Internationale will be the human race’. What they did includes much that makes a mockery of all that. But for all that, they didn’t stop claiming it.

At their peak, various forms of socialism counted their proponents – and their subjects – in the hundreds of millions. Outside communist states, democratic socialists founded their utopian-seeming hopes in the mundane politics of elections, campaigns, and wage claims. They argued that it was in the self-interest of organised labour to defend democratic rights, oppose racial and sectarian division, uphold peace, and so on. As sociological analysis, a sentiment such as ‘Racism is a tool of the bosses to divide us!’ might not be terribly sophisticated, or even true. But, as politics, it works. Karl Marx laid down the law in Das Kapital, Vol 1 (1867): ‘Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.’ The same logic applied to other forms of oppression. When socialists reneged on these commitments, as they all too often did, their own fundamental principles (and principled fundamentalists) could be called on to bring them to account.

This is so astonishing that it’s easily overlooked. In terms of appealing to the common interests of humanity — even if purely as a cover for smaller or more sordid interests — only the great religions have attempted anything like it. No other secular ideology has tried to be a totalising force in the same way. Partly in reaction to, and partly in competition with, the communist challenge, a common sense of universalism and common humanity did become institutionalised after the Second World War in the UN, in a system of human rights and the development of other instruments of international law. Inspiring as this liberal, global humanism was, and real as its achievements have been, it has lacked socialism’s firm footing in the material self-interests of individuals.

Now, with the death of communism and social democracy’s struggle to sustain its postwar gains, the idea of the whole of humanity as a potential political subject barely exists. Socialism is dead, and its death — as Nietzsche observed of God’s — has had unexpected effects. One of the less happy consequences of the end of socialism as a mass ideology is the end of humanity as an imagined community. This has consequences in our real communities; the rise of far-right parties across Europe is one of them.

The aims of those who held the reins of power in communist states may have been little more than to keep hold of them by any means possible. But the aims of most of the millions of ordinary people who believed in socialism were modest: full employment, social security, free education, and healthcare. For almost a lifetime after the Second World War, it seemed as if these were obtainable within social democratic capitalism. But they seemed, paradoxically, to depend for their credibility on the far-off but, to some, alluring prospect of abolishing capitalism altogether. I well remember Britain’s late-1970s Labour prime minister, James Callaghan, declare that we would eventually establish in Britain a society based on the principle of ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’. Strangely, he was not denounced as a communist; it was understood that such grand aims were right for sentimental songs and May Day speeches. But as soon as the grand aims were abandoned, the modest gains were snatched away. Now we are told from every respectable outlet that the gains were unaffordable and the aims were deluded all along.

The challenge for humanists and liberals in the face of a transhuman future is daunting: to replace the socialist project — or to revive it. Without something like it to underpin a sense of common human identity and common human interest, people will divide on the basis of other identities. Many on the left, of course, have found in identity politics a replacement for the universalism of their past. But identity can also be seized on by the far right. It can feed a resentful indifference to the plight of others that comes from having one’s own plight disregarded.

All right. So the aim of a peaceful, global community of equality, reasonable security, and material abundance was a fantasy. Make us drink that cup to the dregs, but don’t expect us to be humanists after we’ve wiped our lips. If labour in the white skin can never emancipate itself, why should it care if in the black it is branded?