It’s surprising how stressful the first time can be. For months now, I’ve been researching the history of hypnosis for a book on the power of suggestion. But no study of hypnosis would be complete without trying it myself. Which is what led me to the door of my friend, the photographer Meghan Dhaliwal, with butterflies in my stomach. At a dinner party a few nights before, I’d mentioned my plan to learn hypnosis. Meghan had piped up immediately: ‘Oh! I want to get hypnotised! Can you hypnotise me?’

A hypnosis researcher had pointed me to a script – or induction – that I was to read in order to hypnotise Meghan, but I’d never even seen someone hypnotised before, let alone been the one doing it.

My only prior experience with hypnosis was onscreen. I knew that certain people can make others drop into a trance by looking or talking at them. Sometimes, a pocket watch would be involved. In the movie Now You See Me (2013), a stage magician hypnotises a guy in the audience to rob his own bank. In The Manchurian Candidate (1962), a man is programmed to kill the president. Hypnotists occasionally have twirling spirals in their eyes, and cartoon snakes are especially deft. But if you screw up – as happened in Office Space (1999) – the victim might be permanently altered or harmed.

I didn’t know, back then, that I had simultaneously underestimated and overestimated the power of hypnosis, a practice long tied to madness, miracles and the secrets of the occult. While it turns out that hypnosis isn’t the key to mind control or a way to contact the dead, it remains a potent means of healing some kinds of illness, easing depression and overcoming pain – hardly magic, but one of the great overlooked brain phenomena of our age.

Some trace the first hypnotists back more than 4,000 years to the sleep temple of the Egyptian priest Imhotep; others to ancient Greece. The original source of the induction techniques familiar today is probably the Roma, or Gypsies, who would have brought hypnosis from India to Europe 1,000 years ago.

The modern incarnation of hypnosis can be traced to the 18th-century German priest and exorcist Johann Joseph Gassner, who believed he had the power to channel God’s word through his own voice. By speaking in a calm and commanding tone to his patients, he could reportedly rid them of all sorts of demons that today we might call epilepsy or muscle spasm. In one case, he is said to have commanded a patient to slow down his pulse in one arm while speeding it up in the other.

Gassner’s work was spotted by Franz Mesmer, a German gentleman scientist who theorised that magnetism controlled the tides (it doesn’t), planetary movement (it doesn’t) and even health (it really doesn’t). He wore a striking silk coat with a silk liner to keep his magnetic power in, and would often carry an iron rod to wave over people, or treat them using small magnets.

When Mesmer saw Gassner, a light went off. The priest wasn’t channelling God, he was channelling the magnet juice that permeated the Universe (which Mesmer attributed more to Gassner’s metal cross than to his voice).

Soon, Mesmer was doing hypnosis, too. In Paris, he had a salon where he would ‘mesmerise’ people for hours at a time until they were either cured or had foaming-at-the-mouth fits. Many of his clients were women, and later scientists attributed his effect to the malleability of their gender, but it was more likely due to their gender’s boredom in 18th-century Europe.

Mesmer’s most famous client was Marie Antoinette. Her husband Louis XVI at first welcomed Mesmer to Paris but soon became suspicious and formed a panel of eminent scientists – including Antoine Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, and Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the United States – to evaluate Mesmer’s techniques. The result was a wonderfully entertaining scientific treatise that discredited Mesmer’s magnets and foretold the era of placebo-controlled trials. But the team also sent a secret memo to the king, pointing out that a person under the power of hypnosis would be easy to sexually assault.

Not long after, Mesmer was roundly discredited; but, while he faded into obscurity, his technique did not. The Goan monk Abbé Faria – whose life included efforts to topple two governments and a stint in the French island prison Château d’If – picked it up from one of Mesmer’s students in the early 19th century. Except Faria said that magnets had less to do with mesmerism than the mind of the person being mesmerised.

In the 1840s, the Scottish surgeon James Esdaile stumbled on hypnosis quite by accident and claimed to have performed 300 surgeries using it as anaesthesia (chemical anaesthesia not having been invented yet). His speciality was painful surgeries involving a build-up of fluid around the scrotum but hypnosis was used for amputations too.

One man got attention for robbing a bank after being hypnotised to do so. The papers left out his history of robbing without hypnosis

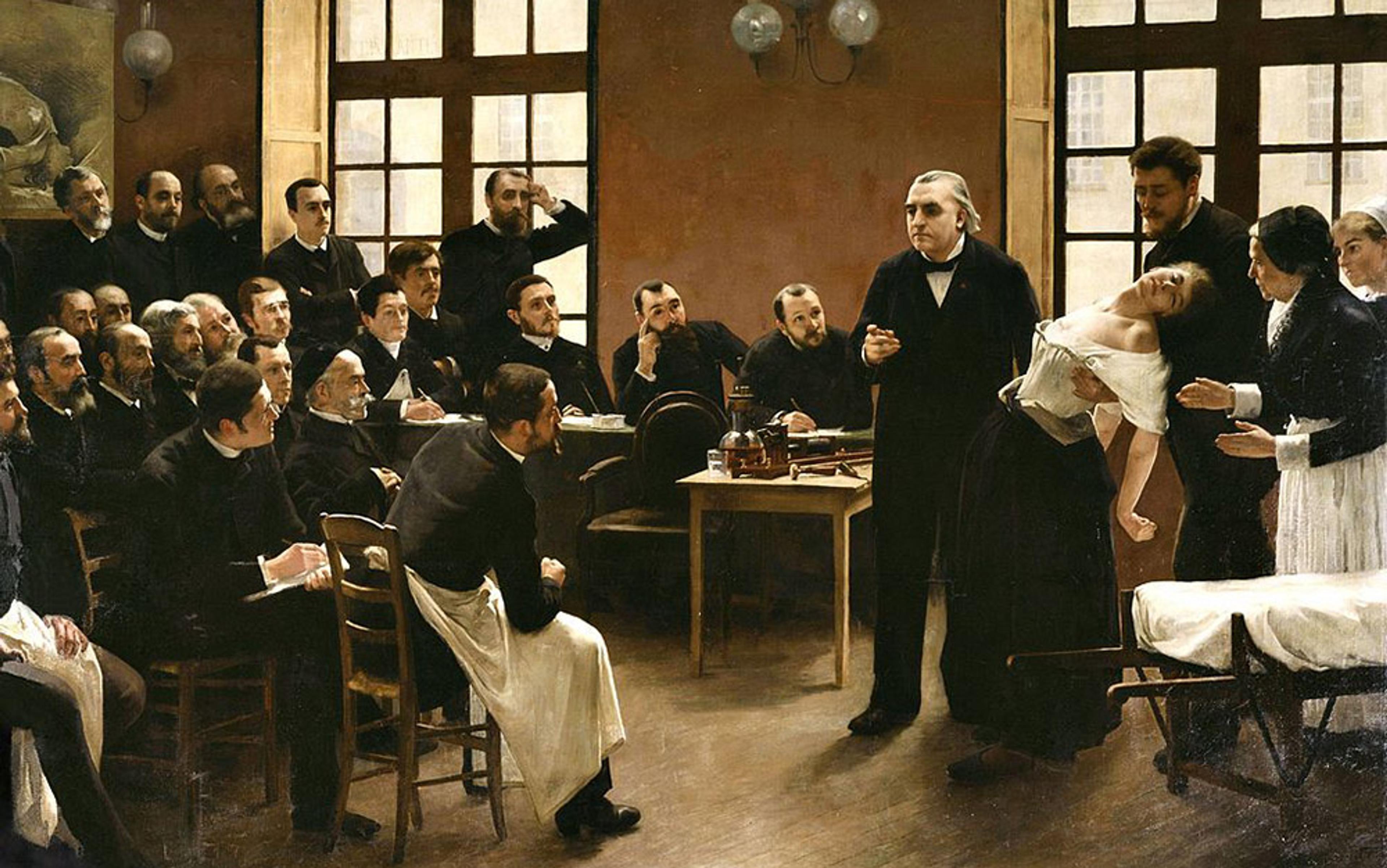

Perhaps the greatest of the 19th-century hypnotists was Jean-Martin Charcot, often called the founder of neurology. For him, two elements turned out to be especially important. The first was hysteria. Today we tend to think of it as a state of frenetic, senseless terror. But back then it was a sort of catch-all term for diseases that resisted categorisation, such as those of the mind that had a direct effect on the body. Charcot noted that certain people with paralysis could be hypnotised to move, while others who could move could be hypnotised to feel paralysed. Such cases led him to wonder if hypnotisability might be part of the disease itself.

A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet (1857-1914) featuring Dr Charcot. Courtesy Wikipedia

The other avenue that interested Charcot was hypnosis and crime. Victorians spent a fair amount of time worrying they might get robbed, raped or killed by someone under the power of hypnosis. It was such a concern that two factions formed within the nascent psychology field: those who thought this was possible and those who didn’t. Charcot was an avid believer that it wasn’t possible to hypnotise a person against his or her will, or to force them to do things they didn’t want to. Hypnosis made you suggestible, his logic went, not psychopathic.

But the public and press disagreed. One well-publicised case involved a man who killed his lover then tried to commit suicide and blamed hypnosis; it’s more likely the fellow was just unhinged. Another man got widespread attention for robbing a bank right after being hypnotised to do so. What the papers left out was this man’s long history of robbing banks without hypnosis.

Through most of the 19th century, hypnosis bloomed right alongside the related field of ‘psychical research’, which examined the supernatural. Séances, ghosts and extra-sensory perception were deemed vital areas for psychologists, and their primary tool was hypnosis. At the same time, stage hypnosis spread across Europe and the US, with magicians and con-artists working mind control into their acts. The best of these, the charismatic Scottish magician Walford Bodie, made outlandish claims and performed even more outlandish feats, such as making unsuspecting victims (often in his employ) walk like chickens. Bodie was an unabashed rascal and an inspiration to Charlie Chaplin and Harry Houdini, but he wasn’t great for hypnosis.

Ultimately, the taint of pseudoscience plus fears of mind control spelled doom for hypnosis research. It all boiled over in September 1894, in a hypnosis performance in Hungary during which a doctor (reportedly, with the stereotypical Rasputin beard and piercing eyes) induced Ella Salamon to travel with her mind to a faraway city. But the young noblewoman had a fit and inexplicably died. It’s not clear what happened, but it was the last straw for hypnosis – it had become dangerous and taboo.

The Dracula story is a classic example of its fall from grace. In the book, published in 1897, the heroes use hypnosis to track down the vampire. But by the time Bela Lugosi donned his cape for the movie in 1931, it was the bloodsucker who used hypnosis, a tradition that continues to this day in TV shows such as True Blood (2008-14) and The Vampire Diaries (2009-). For much of the 20th century, it was actually illegal in Britain to show hypnosis on TV for fear of entrancing viewers against their will.

Meghan greeted me at the door with her boyfriend, the photographer Dominic Bracco. I’d known Dominic for years and had worked closely with him all over the world. I couldn’t help noticing that he was acting a little awkward. I couldn’t really blame him; it’s a weird dynamic. Oh hi, good to see you, sure – take my girlfriend into the bedroom and put her into a trance. For a brief second, I understood how Louis XVI must have felt about his wife hanging out with Mesmer.

The induction script I’d brought was a simple text designed for dental patients afraid of the dentist’s chair. In theory, after hypnosis, a person normally petrified of drills will happily sit through a root canal. Earlier, I’d gone through the script and removed all dental references.

Meghan sat down on her bed, closed her eyes, and I started reading. I began by describing a 20-step staircase that she would slowly walk down: 1… 2… 3 steps… breathe, relax with each passing step… 4… 5… feeling yourself getting deeper and deeper into relaxation; 6… 7 steps down the staircase… nice… perhaps you’re noticing the heavy, restful, comfortably relaxing feeling spreading down into your shoulders, into your arms… Somewhere around step 15 or so, Meghan actually looked like she was in a trance. For just a moment, at step 18, it felt as if she was on the edge of some deeper level of relaxation, as if teetering on the brink of an abyss.

I got her to the bottom of the staircase and began the actual suggestion. As I was reading, the style of the writing caught my eye. Instead of the aggressive hypnotism of the movies – ‘You are getting sleepy’ or ‘When I snap my fingers, you will become a duck’ – it was more a passive-aggressive hypnotism: ‘I wonder if you’ll be pleased to notice’ and ‘perhaps ready to become heavy and tired’.

There is good reason to do hypnosis this way. Real hypnotism is not mind control in the way Mesmer envisioned it or as Hollywood depicts. It’s a collaboration between hypnotist and patient. If a patient wants to resist, the whole thing is broken. You can’t hypnotise a person against his or her will, and you can’t make them do something against their morals. Therefore, experienced hypnotists know that inductions are not commands, they are suggestions. Hence the passive tone.

The suggestion I was planting was nothing devious, just the idea that she would feel a sense of relaxation whenever I or Dominic touched her right shoulder, as a dentist might try to calm a panicked patient. After I was done, I walked Meghan back up the stairs of her mind and asked her to open her eyes. She smiled.

‘That was cool. Thanks.’

Had I successfully hypnotised her? ‘No, not really,’ she said. ‘I was listening and trying to relax.’ And then, clearly trying to make me feel better: ‘I had a headache before and it’s gone now.’

The dichotomy between miracle cure and relaxation exercise has confounded scientists for centuries

For many people, that’s all hypnosis is. A nice relaxing meditation, a little like that part of the yoga session where everybody gets to lie down and focus on their breathing. It’s that familiar experience of staring at a faucet dripping into a pool of water until everything else disappears.

But for others it can be much more. Some people under hypnosis feel no pain when being cut into by surgeons. In many ways, this dichotomy between miracle cure and relaxation exercise is what has confounded scientists for centuries. With one patient, you can wield superhuman powers, and with the next – nothing.

That’s what bothered Sigmund Freud, who started out as an enthusiastic hypnotist but craved a more universal theory for mental healing. Psychology’s ugly first child, used by nut jobs and quacks, took a back seat to Freud’s new talk-therapy idea, considered a more effective tool for teasing out mental ills.

But there were always those few iconoclasts who tinkered with hypnosis. In 1951, the English physician Albert A Mason used hypnosis to treat a 16-year-old boy suffering from rare congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, described by the British Medical Journal as a ‘thick, blackish, horny layer’ covering almost the entire body. This horrible disease created a shocking appearance, pungent smell, and near-constant pain. Every time surgeons moved skin from a healthy part of the body to a diseased portion, the healthy skin became covered in the dark, horny lesions too. So Mason tried hypnosis. He started with the boy’s left arm, planting the suggestion in his mind that his arm should clear itself of the painful growths. In less than a week, the scales on his arm peeled off, exposing healthy skin beneath. Next, he treated his right arm, then his legs, then the trunk of his body. His legs dropped 50 to 70 per cent of their lesions, his back lost 90 per cent, and his arms and hands lost almost all of their lesions.

Then there were the psychologists Ernest Hilgard and Emily Orne, who created the Stanford and Harvard scales respectively to gauge a person’s hypnotisability, a measurement that stayed roughly the same over time. Sadly though, years of additional research have not uncovered much that reliably correlates with hypnotisability. It doesn’t track gullibility, intelligence, sex, race, age or any personality trait very well. The Stanford and Harvard scales don’t really even track each other. In fact, scientists can’t agree if hypnosis is some kind of altered state in the brain or just a form of intense focus.

At a certain point, this is all just theory. To get hypnosis, you must go under yourself. Toward that end, I met with David Patterson, a Seattle-based medical researcher and a passionate believer in the power of hypnosis to manage pain. ‘The main reason I know [hypnosis might be right for a patient] is that they are not doing this,’ he said, holding up his arms like a cross to ward off vampires. He’s not kidding: he regularly encounters patients who believe hypnosis is demonic.

It’s not fun to have people fear or scorn your research, and Patterson says he occasionally considers throwing in the towel. But then something happens that blows his mind and sucks him back in. Take a lecture on hypnotism and pain control at a burn unit that he gave at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee in the 1990s. The doctors had been skeptical. When Patterson offered a demonstration, they recommended that he try it on a young man with burns covering more than half his body and an attitude that Patterson called ‘angry at the world’.

It’s almost impossible to describe the agony of serious burns over large portions of your body. Doctors say it is the worst pain a human being can experience. In this case, every time a nurse tried to remove the bandages to wash the man’s wounds, he screamed and writhed in pain, despite a stream of powerful drugs. The patient scoffed at Patterson, saying that he couldn’t be hypnotised. Eventually, he agreed to try it but seemed intent on doing the opposite of what he was told. So, during the hypnosis, Patterson suggested that he would become increasingly tense. As if on cue, the man did the opposite and became relaxed. Within a few minutes, he slipped easily into a deep, peaceful trance as nurses removed the bandages and rubbed sponges over his raw sores.

Another time, in 1996, Patterson met a patient who had come to the emergency room with a rusty axe in his neck. The doctors saved his life, but in the process the man developed meningitis and had to have painful spinal taps regularly. By now, Patterson was a hypnotist at the University of Washington hospital; frantically busy with patients, he set to work fast.

Researchers see hypnotisability as a talent. If hypnosis is a partnership, then success depends on the skill of both participants

‘He was yelling and screaming,’ Patterson told me. ‘I literally had five minutes. So I said: “When the nurses touch you on the shoulder to roll you over, you’ll go into a trance.”’ For most people, a lightning-fast induction followed by a suggestion wouldn’t work. But Patterson got lucky. The patient turned out to be highly hypnotisable. Afterward, when a nurse touched him, the man who had been screaming in pain suddenly became limp and malleable. ‘They would roll him over and he would become flaccid and just wouldn’t feel anything,’ Patterson said.

This is the challenge of hypnosis research. On the one hand, you have some hypnotists who aren’t very talented, and on the other you have subjects who aren’t. And that’s exactly how researchers such as Patterson see hypnotisability – as a talent. If hypnosis is a partnership, then success depends on the skill of both participants.

In ordinary conversation, Patterson stumbles and mumbles and, like many scientists, is easily distractible. But, in his induction, he is instantly transformed: his voice becomes calm, confident and smooth as silk. Patterson began by testing out how responsive I am – having me lift my arm as if it was attached to a balloon and then attached to a weight. From there, he launched into a 30-minute circular monologue. He touched on multiple topics ranging from the pain in my arm to images of me floating in space, a feeling of freedom and peace, and the need to separate my inquisitive mind from a relaxed one. His logic seemed not to go anywhere yet continued forward, spinning around itself, repeating ideas while moving in no particular direction. I had trouble tracking it and soon started to relax. But I struggled to enter a hypnotic trance. I imagined myself floating in space, starless but adorned with yellow and red nebulae that passed me by. It felt nice, but every few seconds I’d start wondering whether I was hypnotised, which broke the spell, and I’d have to start again.

I don’t appear to be terribly hypnotisable. Patterson later said I was probably around a 3 (out of 12) on the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. It came as a bit of a disappointment. A few months before, I would have been proud of myself – as if my failure to be hypnotised was some kind of superpower. But now that I understand the formidable power of hypnosis, it just feels like failure.

At its heart, hypnosis is a form of storytelling – as primal as two cavemen sitting around a fire – yet I had relied too much on the script. So, a few months later, I was back at Meghan’s door, determined to hypnotise her. This time, I would use the same induction but tailor it to what she needed.

A few weeks before, Meghan had had an adverse reaction to a tetanus shot that triggered a shooting pain across her back, neck and shoulders. Her doctor said there wasn’t much she could do but wait until it faded. It was a perfect opportunity for me as amateur hypnotist to ride in to the rescue. Just as before, I had her imagine the stairs and slowly descend them. I walked her down from the 20th step to the first, reading from the script. But then I tried my own treatment. I told her to imagine seeing her own back muscles, creaky and covered in cobwebs. I told her to imagine them vividly, and to inspect them for a minute.

As I spoke, I realised how hard it is to keep a rhythm while painting a vivid picture off the cuff for the patient. I spoke in my best hypnotist voice – smooth, even, soft but not too soft. I tried to use visual and evocative words that would stick in her mind and allow her to envision her pain evaporating. To counteract the hot sensation of pain in her neck, I tried to use cooling imagery. I said to imagine the cobwebs melting away like ice on a sunny day, revealing perfect muscles, free to move without pain. I described her muscles working smoothly, like a well-oiled machine. Then I walked her back up the stairs.

As before, there was a moment of awkwardness when she woke up. I wondered how Patterson was able to shift his hypnotist voice from such an intimate moment into normal conversation. Meghan smiled. I asked if I had hypnotised her.

‘Yeah, totally. Kinda.’ And then: ‘No, not really.’ Was the pain gone? She shrugged. ‘It’s a little better.’ I sighed and took it as a small victory.

For more than 200 years, scientists have wondered about the mechanism of hypnosis, and recent studies have finally begun to shed some light. Patterson’s regular collaborator, Mark Jensen, has worked with electricity patterns (or waves) on the outside of the brain. If you imagine the brain as a football stadium, with each braincell an individual fan, then a brainwave is like the stadium raising its collective arms in sequence, creating a wave (but keep in mind that, using this analogy, the actual brain is about 1.2 million football stadiums watching thousands of different games at the same time).

Jensen sees a propensity towards two waves in particular – alpha and theta waves – that seem to take over wide swaths of the brain during hypnosis. Both are very slow – from four to 12 waves a second (faster brainwaves, like when you are frightened or excited, move 10 times quicker) – and are associated with sleep, meditation and profound rest. But the brain is a big place and it has a lot to do. At any given moment, part of your brain might be relaxed and slow, while another is working hard.

Tweezing out which regions are most involved with hypnosis is expensive and time-intensive, but that hasn’t stopped David Spiegel, a psychiatrist and hypnotist at Stanford University. Raised by a doctor who learned hypnosis to treat pain and anxiety on the battlefield of the Second World War, he’s been immersed in the practice his whole life.

‘There is this persistent idea that either hypnosis does nothing or it’s terribly dangerous’

‘It’s something of a genetic illness in my family,’ he said, dryly. ‘The dinner-table conversations were pretty interesting.’

He got into it seriously as a young doctor when he met a teenage patient who’d been hospitalised for asthma every few months for years. A single hypnosis session got her wheezing under control and, before long, her trips to the hospital ended too. But not before a nurse filed a complaint over his hypnotising patients instead of the prescribed treatment of powerful steroids. The experience taught him about the potential and peril of using hypnosis: a potential to ease suffering and a peril to one’s reputation.

‘There is this persistent idea that either it does nothing or it’s terribly dangerous,’ he said. ‘People think you lose control with hypnosis – you really gain control. You teach people how to better manage their minds and their bodies.’

It occurred to Spiegel that people’s fear could be based on ignorance. So today he works to understand the mechanisms of hypnosis the way we do any other brain process. This year he published a study that examined the brain scans of 57 highly hypnotisable people and found three significant changes in how their brains responded to hypnosis. First, their dorsal anterior cingulate cortex – a part of the brain an inch or so behind the eyebrows, involved with determining what to worry about – ramped way down. So did the network involved in self-reflection and self-awareness. And lastly, the part of the pre-frontal cortex, where we think about performing tasks, became more connected to the somatic area – which interfaces with the body.

In other words, their brains became less aware of themselves, less interested in consequences, and opened up a pathway to a lot of the bodily functions we either can’t or don’t think much about. ‘It’s a state of highly focused attention/absorption – like looking through a telephoto lens of a camera. What you see, you see with great detail but you lose context,’ he said. ‘You put outside of consciousness things that ordinarily would be in consciousness.’ Meanwhile you get access to things normally outside your control.

These results are very similar to a 2008 study involving people sensitive to electricity when presented with a cellphone. The condition has been difficult to treat because it’s often evanescent and not clear if it exists in the brain or the body. Yet the effects of so-called electrosensitivity can be crippling, while many doctors just throw up their arms, saying: ‘It’s all in their heads.’

But what if certain psychosomatic diseases were actually a form of self-inflicted hypnosis? What if, somehow, they have hijacked their own somatic centre? Peter Halligan, a psychologist at Cardiff University, has been working along these lines for years. Partly inspired by 150-year-old research by Charcot, he has looked at things such as hypnosis-induced paralysis. He’s found that the brain of a person hypnotised into paralysis is nothing like that of someone who is pretending to be paralysed, but very much like some conditions in which people seem to be paralysed without an obvious cause.

Unlike Spiegel, Halligan doesn’t perform hypnosis himself, and came into it almost against his will.

‘I moved into the area of neuropsychology because I wanted to avoid having to discuss things like hypnosis, which I didn’t feel were very credible,’ he said.

But he quickly found hypnosis to be a treasure trove for clinicians and scientists alike. He is especially interested in mimicking real diseases using hypnosis to make them easier to study. He’s been able to mimic ‘visual neglect’ – a condition in some stroke victims where half of the world seems to disappear – and prosopagnosia – which makes people unable to recognise faces. Interestingly, he doesn’t have to describe these conditions for people to show all of their myriad symptoms. It’s as if a part of them somehow knows already.

‘Everything that we experience in consciousness is the product of the unconsciousness’

A team at Macquarie University in Sydney has got particularly good at this as well, simulating the Cotard delusion (where patients believe they are dead) or the Capgras delusion (where patients believe their spouse is an imposter). And in select cases, the hypnotised person exactly resembles a real patient in actions and brain activity, creating all kinds of opportunities for experts to understand the illness.

‘Once you’ve generated them in naïve subjects, you can interrogate the individual afterwards and say: “What was it like?”’ Halligan explained. ‘You can’t do that with patients.’

This becomes an invaluable tool to understanding mental illness and brain damage, in the same way that a rat can simulate human cancer or a laboratory test can simulate a chemical reaction in outer space. It’s also driven Halligan to the conclusion that our unconscious mind has a much larger effect on our consciousness than anyone had ever guessed.

‘Everything that we experience in consciousness is the product of the unconsciousness,’ he said.

Jensen and Spiegel don’t go that far but both tell me that neuroscience is proving why hypnosis should have an important role in medicine today. Hypnotic pain relief alone could save the US billions of dollars in lost revenue, as well as the horrendous repercussions of addiction. Despite what Freud said, hypnosis is not addictive but many of our current pain treatments are.

‘We have tons of evidence that hypnosis is a highly effective analgesic treatment. And yet we are addicting millions of people to opioids,’ he said.

The more I understood about hypnosis, the more confused I was why so few people have studied it for generations. Spiegel said he’d seen a definite uptick in interest among colleagues, but it’s still the Rodney Dangerfield of psychology – it can’t get no respect.

And I can’t say that I fully get it myself – that I’ve ever seen it, even after all this work. So once more I found myself at Meghan’s doorstep. This time, instead of jumping right into the induction, we sat down in her apartment for a few minutes to chat. She was concerned about a deep sense of anxiety that crept up on her sometimes, and we discussed it in vivid terms.

Now, instead of seeing hypnosis as some kind of goal, I approached it as a process. Less like a magic trick and more as an exercise to get in shape.

When we got started, rather than read or modify a script, I went freeform. I asked her to imagine walking up a flight of stairs and then start flying through the night sky, much as Patterson had had me do. She flew over cities and a farm she loved in Denmark, and then finally into black space. As she floated in silent, calm space, I had her imagine her troubles seep out of her body and form bright, colourful bubbles that easily slipped off her. Then I brought her back to the staircase and slowly walked her down.

She opened her eyes. Did I hypnotise her?

Well, kind of. ‘It was like being underwater but being able to breathe,’ she said, adding that the bubble imagery creeped her out.

She described a feeling similar to that 18th stair the first time I’d tried to hypnotise her, except this time she wasn’t scared of it and felt more in control. Most encouraging of all, she felt the deepest level of relaxation towards the end of the session, just as I was bringing her back to the world of the waking. Experiment with underwater imagery, but avoid bubbles, I told myself.

I’m not sure that I helped Meghan. But as we said goodbye, we agreed to try again the following week. After all, we both need to hone our skills.

Reporting for this story was supported in part by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.