We had no idea when our father was coming home, and so my brother and I told ourselves that Dad was dead. He hadn’t left kindly, with hushed words and reassurances, a slow progression from bedroom to spare room. He’d got up one morning, packed his bags and disappeared. Bought a single ticket to India with his new, Italian girlfriend.

My mother says that this is when I changed. Aged six. From bold, bright and confident, to mute and pale. I folded into a shell, forgot my smile. I have memories of school, on the scratchy library carpet behind my friends, and of losing my voice, a perpetual lump in my throat.

It was 1979. The era of the rotary dial. He didn’t phone; apparently there were no telephones at the ashram; or perhaps he did once, an Indian receptionist asking my mother to accept reverse charges. A voice lurching and tripping through a crowd, the shrill of parakeets, tears of laughter and joy drowning out the remains of all that was familiar about him; invisible hands pulling at his clothes, slipping the cotton from his back. Was he an angel? Was he in heaven? Far above us in the sky. We, his family, forgotten in our muted grey; the slow rhythmic drip of waiting. ‘You have children here,’ my mother said with deliberate calm. ‘Please think of them.’

Six months later, he was back, and we met on Hampstead High Street. I’d stuffed my hands into my duffel coat to try to stop the shaking. My toggles done up for comfort, navy tights, Start-rite shoes. My hair was static, heavily brushed, and cut into a bowl. My brother wore a blazer, and a long Doctor Who scarf. It was a grey October day; that perpetual flat-toned ochre of autumn. Our father stepped from his Citroën DS Safari, our beloved family estate that was to be towed away within the year, having been abandoned, sinking into the pavement, tree sap gumming up its windows. Why not? Cars were trappings, like bills, a mortgage, a family home, designed to hold you captive against the needs of the primitive self.

He appeared smaller than his six-foot-five, tanned and thin from dysentery. His shoulders a hanger to oversized clothes, more monkey than cuddly bear. His smile was beatific, and his eyes on the horizon. His girlfriend remained in the car, dark fuzzed-up hair, clothes of orange to faded red; she was a stranger to us then. And our father? He was dressed in a purple Ellesse vinyl-mix tracksuit with plastic elbow patches and gaiters, and a long beaded necklace; an outfit that shouted at us that it had been chosen by her. Sweat gleamed on his forehead, despite the London chill, as if he’d brought the heat with him. His beard was wild and flecked with gold.

Later, from the comfort of his lap, I was to smooth the beads of his mala, beautifully brown, round and shiny, mesmerised by the photograph in a gold-rimmed pendant of the man my father had given himself to, all white fluff and soft focus, save for those deep brown, heavy-lidded eyes. What is it about him? I was to ask. Why? Over the coming years, my brother and I spent many hours staring at videos of Dad’s guru in discourse, his drawn-out whispery vowels, forcing our eyes to remain open so we could catch him out when he finally gave in to blinking.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh was first known to his followers simply as Rajneesh, variously translated from Sanskrit as the ‘Blessed One Who Has Recognised Himself As God’ or, more accurately, the ‘Holy Glorious Lord of Darkness’, then Bhagwan, and later, after a run-in with the US government, he changed his name to Osho. Love, he said. Love is everything and nothing at all. It is the light and darkness that lives in us. It is that which we cannot categorise or define. To categorise is to limit, and to limit is to deny. It lives in us. It needs to be free.

Born in 1931, Chandra Mohan Jain, as he was first called, was the eldest of 11 children of a cloth merchant in a small village in central India. As a student, he was rebellious and argumentative, but gifted, and after earning a degree in philosophy, he progressed to public speaking and academia. In 1953, aged 21, he claims to have become enlightened, drawn to a maulshree tree, where ‘everything became luminous … the benediction, the blessedness’. His personal teachings evolved from a small apartment in the sticky heat of Mumbai, where he initiated his first sannyasin (Sanskrit for disciple), to the cooler climate of Pune.

Bhagwan took his influence from a number of philosophies and religions, a kind of potato smash of Eastern Hinduism, Zen and Western psychotherapy. At the heart of traditional Hindu philosophy, as quoted by the Indian scholar Sri Shantananda Saraswati, is the belief that ‘to begin to be what you are, you must first come out of what you are not’. Bhagwan’s movement grew from this premise: shed the ego, your neuroses, the artificial constructs inherited from the inevitable damage of our society and generations of family, and the everyday demands of living in the civilised world, and you will discover your essence – the true you. He believed in an ideal state, primitive and innocent, and he wanted his disciples to aspire to this freedom, too, through love, surrender and sex.

‘I have a new name,’ he said. ‘From now on, I will be known as Purvodaya.’ Pooh-va-what?

Bhagwan’s devotees should live in harmony with everyone and with nature. They will be ‘creative’ – able to transform their repressed energy into something productive such as music or poetry. They will live in love. A mostly Indian following soon grew to include crowds of Europeans and Americans, mostly middle-class, educated and wealthy, emerging from the 1960s sexual revolution, glancing back at their parents’ generation as the oppressors.

‘I’ve been reborn!’ our dad told my brother and me that day in Hampstead. ‘The man you knew before is no longer.’ I dug my hands deeper into my duffel coat and stared up at him. ‘I have a new name,’ he said with affected elation. ‘From now on, I will be known as Purvodaya.’

Pooh-va-what? My brother and I frowned up at him, caught suddenly by an abrupt blast of fleeting sunshine. But if you’re no longer the man you were, does that mean you’re no longer our father?

There was an element of ridiculousness, even to us at such a young age – our dad masquerading as a clown, standing on the stage of someone else’s play. My brother nudged me, and we caught eyes. Perhaps it was a passing phase. But we were children, prone to accept and forgive. We were curious, open, trusting, and we loved him. His distance from us made him only more compelling.

In my late 20s, researching my first novel, I wrote to my father and asked him about his life. Then recently, when moving house, I found the letter he sent in reply, telling me of his early job as a truck driver, then climbing the publishing ladder, from sales to running his own business; his restlessness in his marriage with my mother (he spoke of his infidelities as a kind of compulsion); why he became a sannyasin. Of his time in Pune, he wrote about a moment before dawn, joining a line of men and women gliding through the dark, dressed warmly in coats over red robes, hoods, socks and comfy shoes. It was the daily procession to the morning’s Dynamic Meditation, where they screamed and roared, punched pillows, and sometimes each other, as a prequel to stillness. ‘Everything was silent,’ my dad wrote, ‘except the Indian tea-wallahs beside the road with their carts. It was the most magical moment. It will stay with me forever.’

In Pune, the sun was warm and the light rich. Sannyasins lived in wooden huts, and wore lunghis, home-dyed in sunset shades of orange, maroon and pink, the traditional Hindu holy dress, but without asceticism – Bhagwan’s disciples slung their malas around their necks or under an arm while they danced or made love. They worked as a community, cooking, digging, picking fruit, while their red-ragged children played in the dust and dirt. They faced their fears beneath sweeping canvas canopies, their shoulders rocking, and arms to heaven, to the rhythm of live drums and a background of light, heat-haze and bamboos. They breathed chaotically, and hooed, collapsing on the ground, forming pink stars of spent bodies. During his 90-minute daily discourse, Bhagwan sat before his coral-clad followers and imparted his wisdom with laughter in his eyes and hands pressed together in namaste. To be a sannyasin was to be open – absorbent as a sea sponge and light in the wind. His followers drifted in a perpetual state of ‘bliss’, trance-like, dreamy and disengaged. Bhagwan discouraged ‘listening’; instead people should meditate, let his words swim on a wave.

Here, my father felt free to be himself. He could wear a skirt, a faded pink bandana around his head; he could eat watermelon. He could take many lovers, which he did. ‘It is very hard to describe it all,’ he writes. ‘Not because I don’t want to, but because the reality was only in the feeling and the being, and not in the mind and therefore couldn’t really be memorised at all.’ I have since recognised that this is the language of the heart – the soft, oblique realm of the unconscious. But it is also the innocent space that a child knows, both creative and naive.

I look out for these kids in their hand-me-downs, small and adrift. I wonder about their freedom

My father was raised in a quiet corner of southeast England, where very little happened. His parents were aspirational: his father an engineer, his mother a department shop girl. He was the product of a childhood prematurely broken by boarding school: ‘Man up,’ his father had warned, when his son screamed to be taken home. But home, with all its acrylic comforts, was claustrophobic – stuffy in the winter and slow in summer. This mundane existence drove my dad and many others like him towards a more fluid and sensual experience. I wonder at times if our life in London, that Hampstead street, became his evil, all that held him back. A world where you answered to no one was compelling. It doesn’t have to be this way, said Bhagwan, who clapped at his devotees to finally ‘Wake up!’ They had been let in on a secret, they were now chosen.

Bhagwan gave his disciples permission to abandon their responsibilities; those things that burdened them with a certain dispassionate duty. The needs of ‘the self’ were paramount. ‘He created a kind of structured carelessness,’ my father describes it. ‘If another person was suffering from some emotional problem – jealousy, anger, fear, doubt – it was their problem.’ My father admitted to being a mess when he first joined the movement, having gone through various therapies to try to address his restlessness. According to him, it had worked. After his darshan or audience with Bhagwan, when he was given a mala and a new name, he grew more settled, though, of course, his life didn’t.

Some sannyasins took their families with them, to raise their children in the commune. While the adults stopped on the dusty paths to hold each other in an embrace, the children stopped beside them to look up and watch, like expectant baby elephants. It was an experiment that these devotees were prepared to give themselves up to, whatever the risk.

Revisiting footage of the ashram from the 1970s, I look out for these kids in their hand-me-downs, small and adrift. I wonder about their freedom. What these children did with this gift, whether they even wanted it. Where are these children now? Many of them would be my age, mid-40s. I wonder how they’ve carried this formative experience of colour, light and lawlessness. In light of studies on the challenge for those who’ve grown up in cults to adapt to the wider world, I wonder how many of them are still alive?

Soon after returning from Pune, my father and his girlfriend rented a small top-floor flat in Primrose Hill, and their existence became about when they could finance their next trip to India. We were left behind as an afterthought, to become merely an anecdote that belonged to a time when Dad didn’t know himself, before he’d spun himself around and chosen the right dusty path. His maroon-clad friends would nod and smile in recognition. My mother was left to pick up the pieces. Their publishing company was taken into receivership; debts accrued. We almost lost our home, set against an unpaid bank loan.

Our house was our castle, our north London street our moat. We knew all the neighbours – my brother got to know a lot of them by way of apology, after accidentally smashing their windows with his football. We spent a lot of our free time outside, cycling up and down, as the local Rottweiler snapped at our feet. We formed our own community: gangs of kids who humorously harassed passers-by. My brother and his friends broke into derelict buildings, scaling scaffolding. It was a quiet, friendly road, where people settled. Live fires flickered through the darker months, and Christmas trees shone. Apple-bobbing parties; marshmallow clouds. We walked into our neighbours’ houses as if they were our own; we washed their cars, fed their cats. Each night, we closed the door, and it was our mother who kissed us to sleep.

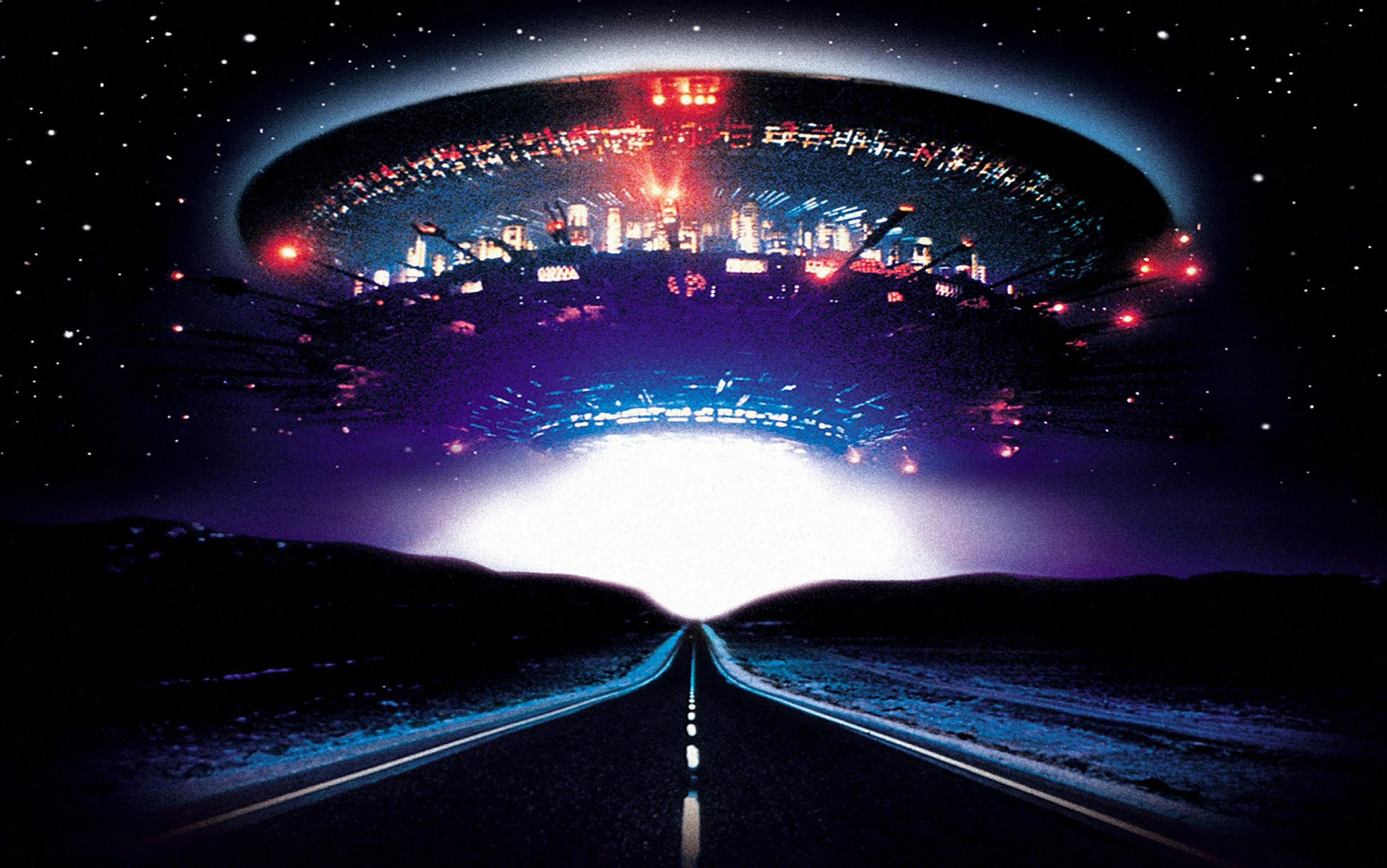

Despite this cosy new family of three, we lived for our time with our father. He became a drug, for me particularly. Buoyed after a weekend with him, I’d slowly deflate as the week progressed, waiting to be energised again. Though he made promises he couldn’t keep, was distracted and absent, a part of me was yet with him on his travels, coat-tailing his compulsion to get his next fix – in India, and later Rajneeshpuram, a city built in Oregon’s wild country by Bhagwan’s followers when they’d outgrown the ashram. I was like a burr attached to his tracksuit.

In 1981, the same year Bhagwan moved to Rajneeshpuram, my father left London for Medina, a commune in Suffolk. Medina was a grand stately home with acres of woodland, where up to 200 people lived and worked until 1985, when all the communes took a hit. On sporadic Fridays, he’d collect me and my brother from school and drive us there for the weekend. We’d emerge from the car in our school uniform, crowded by a group of commune kids, scruffy and skinny, in ill-fitting clothes. I stumbled back when they fired questions, about my school, my age, whether or not I’d hit puberty. The hint of sex that crossed their faces both thrilled and frightened me. At my insistence, Dad bought me a maroon bomber jacket and purple cords from the commune shop. On our next visit, I struggled to get into them on the backseat of his car.

People liked to dance at Medina. It was another form of meditation, of surrender. When sannyasins danced, they closed their eyes, swayed their arms above their heads and swung their hair. My brother and I hung about on the margins, too embarrassed to join in. While the adults formed a sweaty throng, the community’s children sought out their own entertainment: they skidded along the slippery floors, chased each other up and down the stairs, ran barefoot across the lawn. In his memoir My Life in Orange (2004), the late Tim Guest captures life at Medina vividly: ‘As the children of the commune, our role was to run free, to be uninhibited, to say yes, to look beautiful, innocent, uncorrupted.’ And many of them appeared to be just that. Their confidence was radiant. I stood back and glanced shyly from behind my NHS glasses.

My life swung from two extremes, the regularity of school and home, to a place of abandonment. It took a moment to retrack, the Sun at a different angle, a camera refocused. In London and growing into my teens, I was drawn to the troubled kids. Those who bunked off school and hung about the off-licence handing coins to passers-by to get cider and cigarettes. There were sannyasin kids at our local schools, too, with names such as Rajan and Rupa, who turned up at parties, with their long, thin limbs and otherworldly confidence. I hung about them even though they weren’t interested in me, just to feel the sick sensation of adrenaline, that subtle rearrangement of air. They spilled stories of underage sex, of hard drugs and no curfews. When I returned home late from these house parties, my mother grounded me. When my school informed her of my truanting, she chased me up the stairs with a rolled-up newspaper.

They were encouraged to give up their children to the greater good of the multiparent family

My memories of Medina are of open spaces, communal meals, washing up, panpipes, wafts of incense, but mostly a sense of wanting to belong. But there was also brooding anger in the adults’ commitment to surrendering to a perpetual state of joy. There were sometimes gritted teeth behind those smiles. In my shiny bomber jacket, I twirled across the lawn with the other children. In our boredom, we crept up to the therapy rooms, and peered through the gaps in the blackout blinds, giggling as we backed away and hid. We waited for the silence, and for the doors to open, the blast of blood and sweat, as couples came out. But then it all changed: a man had seen us. He grabbed one of the kids and dragged him back into the empty gym, pinning him down on a red mattress. We stood at the door, fear in our throats, to see him lock the boy with his knees and wrap his hands round his neck, shouting in his face. ‘You’re laughing, eh? Now I will show you who’s laughing.’

The school at Medina was chaotic and colourful, and while English and maths were compulsory, everything else was optional. ‘It is up to the children, they will lead us’, was the general approach to teaching. Above all, the most important lesson was in life: children should learn from each other and the adults around them. Only, the adults now appeared to be in regression. At times they dressed in pyjamas and walked through the grounds fondling teddy bears and speaking baby talk.

Some years later, now running a commune in Tuscany, my father was to write a book called Wonder Child (1989). A self-help book for adults, it offered a guide to find the ‘magical world of innocence and joy within ourselves and our children’. It celebrates a child’s ability to live in the present with all its beauty and, following Bhagwan, denigrates the parental tendency to restrict and set rules. This, he writes, is what kills innocence.

Those families who raised their children within the ashram and at Rajneeshpuram were encouraged to give them up to the greater good of the multiparent family. It was forbidden, from the age of five, for children to sleep with their parents. Children were considered to obstruct their parent’s personal development. Many men, including my father, were encouraged to have a vasectomy on joining the movement; many women were sterilised, some when they were young. In a recent series of articles for The New Republic, Win McCormack, author of The Rajneesh Chronicles (2010), writes that among the thousands of followers who lived and worked at Rajneeshpuram over the four years of its existence, not one baby was born within the commune. What of those children who had already been born? Tim Guest’s mother spoke of how she had believed that the community would be a better parent than she could be. But according to Tim, he felt he spent his ‘whole life on tiptoes, looking for my mother in a darkening crowd’.

The one and only time our mother visited Medina, she cried. Hers was a difficult choice: should she cut her ties with our father in order to protect us, or let us negotiate this rocky path in the hope that we would have the wisdom to reject it ourselves? Instinctively, she felt that Medina wasn’t a safe place for us. Still, she was fearful of the fallout should she prevent us from going, afraid that by depriving us of our father, he’d become a messianic mystery.

During those weekends at Medina, I woke up to sex. It was not a particular moment or revelation, it was just around me every day, in displays of open affection and in conversation among the kids and the adults – inappropriate things being said, late-night noises. I learned that sex could be indiscriminate, and that love didn’t necessarily mean monogamy; that kids did it, too, with each other and with adults.

Dad and his Italian girlfriend stayed together during their time at Medina. But during the many empty hours that my brother and I spent waiting outside the meditation room, playing Donkey Kong on our consoles, we’d catch a glimpse of him in a crowd of similarly sunset-clad, bearded men, with a new pair of female hands clasped around his back. Dad told us they were in a consensual open relationship, but then I’d walk in on his girlfriend naked and furious, about to hurl his marble Buddha out the window.

Every time we visited, they’d moved bedrooms. My brother and I slept in the Active Meditation Centre, kept up most of the night by hysterical laugher and sobbing, or in the communal attic, where futons were divided only by clouds of sheer purple organza, and where couples copulated openly. I once crept up the stairs for a forgotten something, only to find a man fucking a woman, while she lay back in a cloud of cosmic boredom, entertaining herself by reading a book. Bhagwan thought that sexual perversion lay behind all mental sicknesses, that civilisation repressed an essential ‘life energy’ by calling sex a sin. In the days before the harsh reality of AIDS gave sannyasins pause for thought, long-term relationships were frowned upon: ‘everyone was screwing everybody else all the time,’ my dad wrote.

Children were not revered for their untainted ability to be present, to be free – they were trampled on

In My Life in Orange, Tim describes the year Medina closed down, when a lot of the children who’d lived there ended up at Rajneeshpuram. They landed, probably spellbound, stunned and dizzy from its size and extreme climate. The commune was also on the verge of collapse, and the atmosphere would have been paranoid and aggressive:

That year, the summer of 1984 at the Ranch, many of the Medina kids lost their virginity; boys and girls, 10 years old, eight years old, in sweaty tents and A-frames, late at night and mid-afternoon, with adults and other children. I remember some of the kids – eight, nine, 10 years old – arguing about who had fucked whom, who would or wouldn’t fuck them.

What strikes me here is that children were not revered for their purity, their untainted ability to be present, to be free – they were trampled on. Innocence violently lost.

In discourse, Bhagwan asserted: ‘Once your own understanding of love blossoms there is no question of attachment at all.’ He referred to traditional Indian Aboriginal tribes whose teenagers – aged 13 to 14, on the cusp of sexual maturity – had sex with every one of their peers before settling down to marriage. ‘With one condition – and this is a beautiful condition – that no boy should sleep with [the same] girl for more than three days … So there is no question of any jealousy, there is no competitive spirit.’

It’s hard to trace Bhagwan’s discourse on sexual initiation, but my father talked about it as if it were a good thing: leaders coming to the commune to give young women their first sexual experience. Perhaps this initiation was seen as a safety net for women to be guided by a wiser, more experienced teacher, but it’s also horribly artificial. It’s worth noting, too, that there’s no mention of roaming bands of older women preying on younger men. There were men who watched me while I played at Medina, making no attempt to hide their desire. ‘She’s cute. She’s going to be a beauty,’ they’d say to my father. ‘He likes you,’ he’d tell me, as if it were normal. My mother was right to be worried.

‘Burn your bridges – go forward,’ says Bhagwan’s notorious secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, in the fascinating Netflix documentary Wild, Wild Country (2018) by the filmmaker brothers Chapman and Maclain Way. It was a movement that thrived on provocation, and the sannyasins made enemies everywhere they settled. Their conflict with the ruling Janata Party in Pune culminated in a knife attack; later, the sannyasins of Rajneeshpuram in Oregon drove out the residents of the nearby small town of Antelope through bullying and intimidation. When the Oregon ranch closed down just four years after its inception, Bhagwan was deported back to India with a $500,000 fine, narrowly avoiding prison for circumventing immigration law to arrange fake marriages. Meanwhile, in an attempt to manipulate the votes in a local election, Sheela led a plot to poison residents in the local county seat with salmonella – the first bioterror attack on US soil; Sheela was later imprisoned.

Using vintage footage from inside the therapy rooms, which are primal and violent, angry and animalistic, the Way brothers show the dark side of sannyasin life. There are stories of sexual and physical abuse, of hierarchy, led by social and financial standing. There are accusations of hypnotism: that the therapies were designed not for their disciples to know themselves better, but instead to lose their minds and judgment. Was this also why Bhagwan was so anti-children? Not only did children get in the way of their parent’s self-development, but also of their devotion to their guru. Instead, he infantilised adults – ‘man should understand himself to be just like a child playing on the sea beach, collecting seashells, coloured stones, and immensely enjoying, as if he has found a great treasure’ – making them weak and dependent. ‘It is Bhagwan who dictates what responsibility looks like,’ says the British psychotherapist Wendy Bristow.

Occasionally, I trawl a website set up for those who lived at Medina. It is not up to date. My father’s entry fails to say that he died 10 years ago of alcoholism. But there are blurred photos of the kids who lived there, and many of them I remember. I study these pictures and the rushed, misspelt notes beside their faces. On the first page, I am shocked to read: She died in 1997, after a long battle with drugs. I scroll down: He died of AIDS in London in 1994. I scroll down: Unknown. Unknown. Unknown.

Those who leave cults commonly feel shame: at their own hunger to believe, and grief at getting it wrong

There was a Facebook page dedicated to a young woman who had attempted to reverse her sterilisation, done at Pune, aged just 19. Years later, she’d fallen in love and wanted to have a baby. She was 33, the same age I was when I saw the posting and had my first child. It is a much more straightforward procedure for a man to reverse a vasectomy than for a woman to reverse sterilisation. The young woman had died.

I have since had conversations with some of those who were raised at Medina, and there is a quiet mention of abuse that took place at the commune school, by one of the teachers; but there is also suspicion at my questions, a shake of the head at further enquiries, and a reminder of my position on the peripheries. This is not my story to tell. I have walked away with a sense that many of these children were not all right; the lucky few, perhaps, had parents in high standing in the community, which was often equated with money; this acted as their protection. I’m also aware that it isn’t easy to reject such a profound and intensely felt part of your life, particularly not when it’s all that you know. ‘We all think normal is the family we grow up in,’ Bristow told me. The American psychotherapist Daniel Shaw, who himself spent years in a cult, and writes about it in Traumatic Narcissism: Relational Systems of Subjugation (2014), says that, even among those who do leave cults, a common feeling is shame, at their own blindness, their hunger to believe, and grief at getting it wrong.

Tim Guest, along with these other Medina kids, was parcelled off to Rajneeshpuram in the early 1980s. ‘I thought I’d given Tim the life and freedom I’d craved,’ his mother told The Guardian in an interview after his death. She was the product of a strict Catholic upbringing. Tim and I crossed paths again as adults, and I was impressed by his burgeoning career as a writer. He was dating a friend of mine at the time, and found the settled life a challenge; I know he struggled with attachment. We lost touch when that relationship broke down, but I was happy to hear that some years later, in his mid-30s, he had married. Then suddenly, he’d died. An accidental overdose after a night of clubbing. He’d been alone, lying in bed with headphones on, a playlist on rotation, the same songs, over and over. He was left vulnerable to the power of transcendence, only it was not through active meditation or dynamic dance; it was not through love or sex, or abandonment. It was through surrender of a different kind. Searching, still, to fill an emptiness, not met. Similar to what eventually took my father.

In his attempt to exorcise the sin from sex, Bhagwan created his own perversion. Blocking its natural outcome by encouraging vasectomies and sterilisation – ‘damning the true creativity of his followers, as Freud might have seen it – children being the creative product of intercourse,’ says Bristow. But also by condoning abuse of the children who were the embodiment of the innocence that he and his followers so revered. My brother and I were lucky, I realised, to have had a conventional home, our castle, with its firm thick walls, strong enough to take the knocks and the kicks, and to withstand the pain.