What follows is a list of ‘natural remedies’, familiar to anyone with more than a passing interest in contemporary natural healing. These were put together specially in April 2020, as a COVID-19 protocol by Cristina Cuomo, founder of the wellness magazine Purist, after she and her husband, the CNN anchor Chris Cuomo (brother of New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo), were stricken by the virus:

- Resonance breathing

- Pranayama meditation

- Liver-cleansing beverage: one raw garlic clove, one orange, one lemon, a tablespoon of cayenne pepper, a spoonful of olive oil, fresh ginger and a piece of fresh turmeric

- Zinc

- Alka C – 3,000 mg per day

- Vitamin B

- Vitamin D

- Glutathione powder

- Quercetin

- Two medicinal florals: xanthium and magnolia

- Viracid

- Vitamin drip: magnesium, N-Acetylcysteine, Vitamin C with lysine, proline and B complex, folic acid, zinc, selenium, glutathione and caffeine

- Water and bleach bath

- Body charger (‘[sends] electrical frequencies through [the] body to oxygenate [the] blood’)

- Portable PEMF (pulsed electromagnetic field) machine

- Ayurvedic food

To the uninitiated, the variety and juxtapositions are surely jarring: Indian meditation alongside a ‘body charger’, fresh juice to cleanse your insides, followed by a bleach bath to cleanse your outside. And then there’s her recurring insistence on the ‘naturalness’ of these interventions throughout her discussion of the protocol. Raw garlic seems natural enough, and so do breathing exercises, but a PEMF machine? Vitamins and minerals that have been processed and refined into powders, pills and drips? Whatever Viracid is? There are many possible definitions of ‘natural’, but it’s difficult to imagine one capacious enough to accommodate the entirety of this list.

Still more perplexing is the repeated conflation of ‘natural’ with anything ‘non-Western’, itself a protean label that embraces not only Indian and Chinese medicine, but also Indigenous medical approaches of all types (including First Nations and Native American traditions), the Hippocratic corpus (from Greece), homeopathy (a German invention), and even chiropractic (developed in Iowa in the 1890s).

This anti-establishment melting pot approach to healing is a global phenomenon, best exemplified by ‘naturopathy’, a popular healing system pioneered in late-19th-century Germany. As the name suggests, naturopathy invokes ‘naturalness’ to bind together what are otherwise fundamentally disparate interventions. At the Immanuel Medicine Zehlendorf naturopathy clinic in Berlin, for instance, patients have an enormous variety of options available: nutrition supplements, high-dose Vitamin C infusions, leech therapy, dry and bloody cupping, and many herbal medicines – drawn from Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Swiss hydrotherapy and ‘Indigenous’ traditions.

It doesn’t matter that these systems are built on fundamentally different metaphysical systems and causal theories of illness. The pathological ‘miasms’ of homeopathy and the ‘yin-yang’ imbalance of Chinese medicine, qi, chakras, chiropractic subluxations, humours, the ‘energy’ that gets refreshed by Cuomo’s body charger or, should you prefer, adjusted by a reiki practitioner – all coexist happily, united only by their supposed naturalness, effectiveness and opposition to what is known, derisively, as mainstream or conventional Western medicine.

Two centuries ago, lumping these together would have seemed completely nonsensical. Each represents a unique set of claims about illness aetiology, developed in different cultures in different time periods with entirely different medical systems. Though the qi of classical Chinese medicine and the Erzeugungskraft of homeopathy seem similar when translated as ‘energy’ and ‘vital force’, they are no more related than the force of inertia is related to the force of Star Wars. Treatments based on qi were developed long before a germ theory of disease; homeopathy concerns itself entirely with microbial adversaries.

In a strange twist, natural has come to include, rather than exclude, the supernatural

To scholars of early medicine, efforts to appropriate ancient traditions by calling them ‘natural’ are completely anachronistic. It’s true that the Hippocratic corpus in Greece (c400 BCE) and the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine in China (c300 BCE) – texts cited reverently in natural healing circles – represented a crucial turn toward naturalistic medicine. But ‘naturalistic’ in this context refers specifically to the rejection of supernatural aetiologies such as demons, spirits, deities and deceased ancestors, along with therapies meant to address them such as exorcism or prayer. Today, natural interventions are typically contrasted with unnatural surgery and pharmaceuticals (‘cut, poison, and burn’ is insider lingo for treating cancer through operations, chemotherapy and radiation). In the ancient Greek or Chinese worlds, the oppositional binary between natural herbal medicines and unnatural chemical and surgical interventions would have made no sense. Since they address illness without recourse to magico-religious explanations, surgery and drugs are natural.

In other words, until recently the standard opposition was not natural and unnatural but rather natural and supernatural, the same opposition that characterises secular scientific naturalism and so-called mainstream Western medicine, which exclude the supernatural. The worldview of modern natural healing, by contrast, extends its inclusivity to a wide variety of spiritual approaches, from shamanic ritual to prayer. The Dalai Lama’s suggestion in January 2020 that chanting mantras to the goddess Tara might help contain COVID-19 would undoubtedly meet with more acceptance from Cristina Cuomo than from her critics. In a strange twist, natural has come to include, rather than exclude, the supernatural.

The inclusion of supernatural healing is made possible by reserving scepticism and scrutiny almost entirely for unnatural interventions. The claims of profit-driven pharmaceutical giants receive zealous debunkings, whereas the efficacy and safety of natural supplements go largely unquestioned – not to mention the more than $100 billion raked in annually by the companies and natural health gurus who hawk them.

Or take the Hippocratic quote: ‘Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,’ ubiquitous in natural healing publications (see, for example, the spring 2019 issue of Purist magazine). Nonsense, according to Helen King, a classicist and leading scholar of Hippocrates. When I spoke with her, she expressed frustration with the appropriation of Hippocratic texts by wellness gurus who seem to care little about its genuine origins. ‘The text it supposedly comes from is almost impossible to understand,’ she told me. ‘It just says food-medicine-medicine-food, and no one knows exactly how to translate it. Certainly not “let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”.’

It’s easy to throw up one’s hands (as I once did) at the strangeness of calling acupuncture natural. ‘How is sticking stainless steel filiform needles into someone natural?!’ Frustration turns quickly into outrage upon hearing about the tragedies that happen under the auspices of natural healing – the needless deaths of children, the family members who spend ruinous amounts of money on rituals destined to summon only false hope.

There should be no sympathy for natural healing charlatans who contribute to the death of children, just as there should be no sympathy for the opioid manufacturers who destroyed countless lives by relentlessly pushing their product. But pharmaceutical manufacturers are not pure evil, and natural medicine advocates are not completely deluded. I have come to sympathise with those who, like Cuomo, turn to natural healing, especially in times of crisis. And I believe that ‘mainstream medicine’ could help itself by taking seriously certain features of natural – and, thus, supernatural – healing, instead of dismissing enthusiasts as credulous or ignorant.

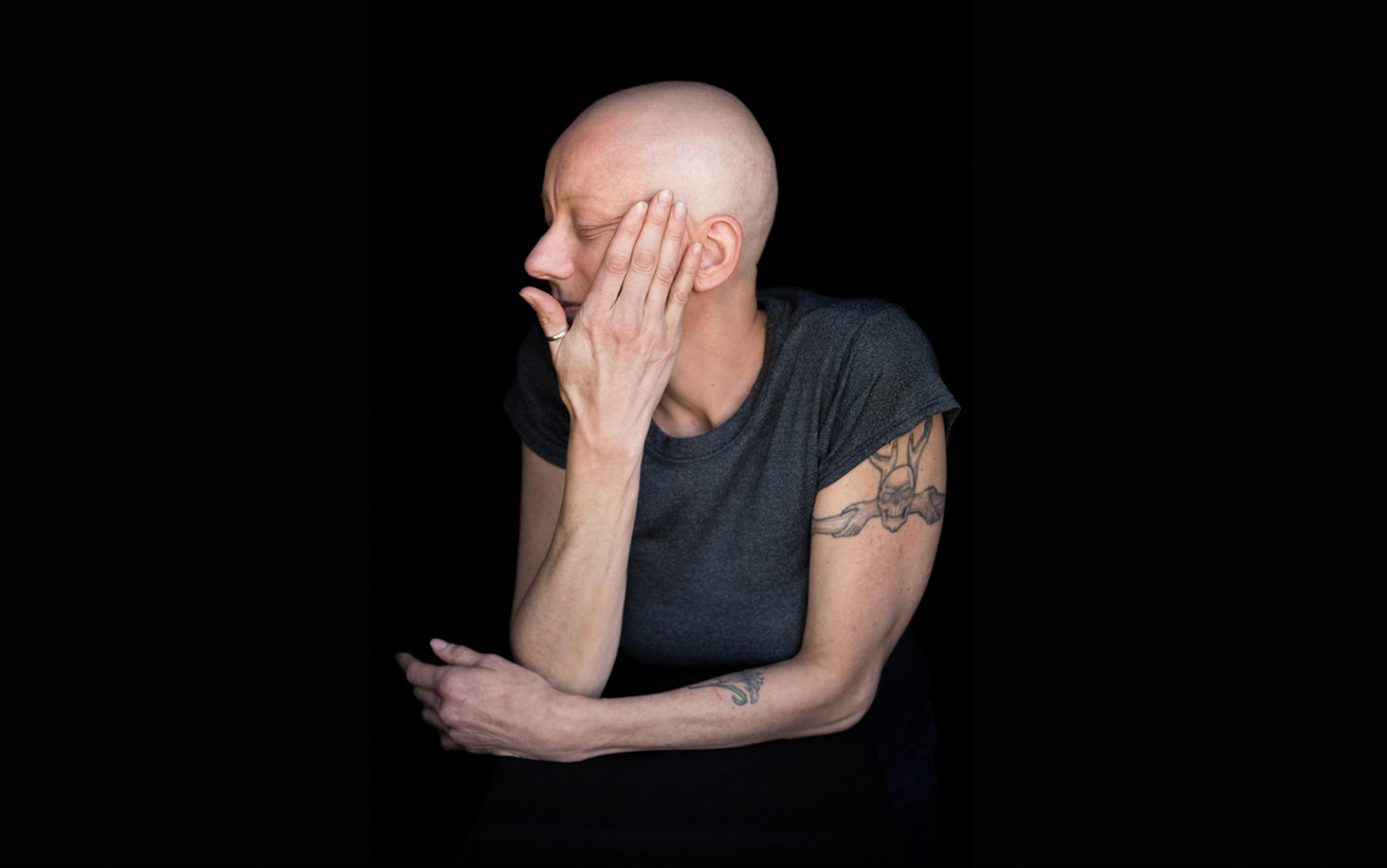

In his book The Illness Narratives (1988), the American psychiatrist and anthropologist Arthur Kleinman argues that the experience of suffering forces two basic questions: Why me? (the question of bafflement) and What can be done? (the question of order and control). These are not merely physiological questions, but also existential matters. Sick humans aren’t just broken machines. When a body breaks down, it’s you or a loved one that’s broken, not an object. This is why cancer patients routinely describe the experience as bodily betrayal. The symptoms of illness represent the collapse of an intimate relationship, a rupture of trust. The consequences of this breakdown in one’s body change the world, which was once a place of relative safety – in certain moments, even a kind of paradise – into hell.

Modern medical science limits itself to the illness itself, not the rupture of trust

By design, modern medical science refuses to offer existential answers. To the question Why me?, the only honest answer is often We don’t know. Even when there is a clear answer – ‘The lung cancer was caused by smoking’ – patients will still wonder why they were stricken when so many other smokers are not. To broaden the answer with an appeal to genetics or environment is no help, since even together these variables can’t explain their own existence. I can still wonder why I ended up with these lousy genes in this lousy environment.

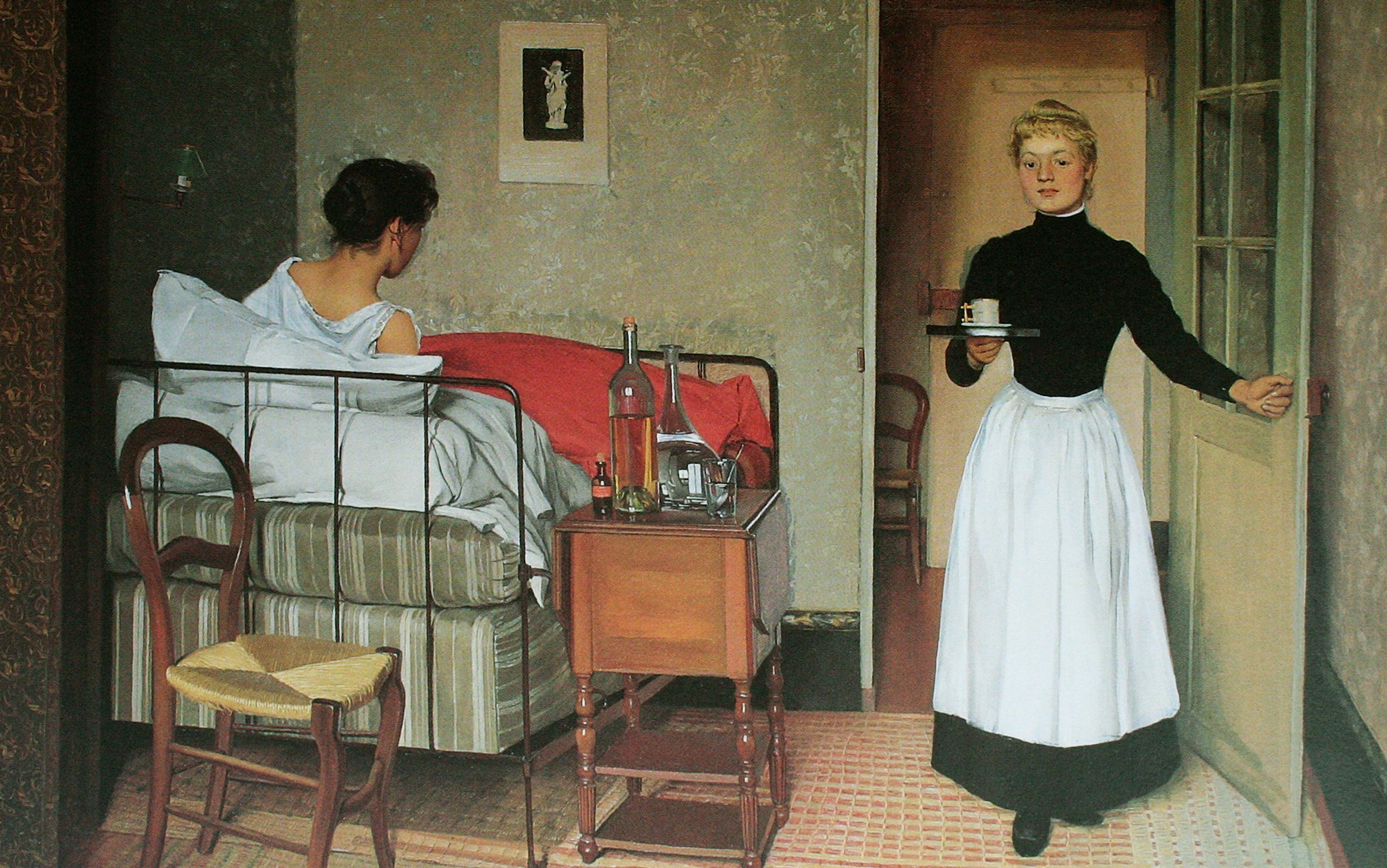

Likewise, answers to the question What can be done? often prove unsatisfactory because modern medical science limits itself to the illness itself, not the rupture of trust. When you’re sick, you want to get well, but that’s not all. You also want to feel safe, that your body and your world will not betray you again, and that you have some agency over avoiding further betrayals. In these vital moments of need and crisis, modern medical science offers little empowerment. It doesn’t tell us stories about a harmonious world and the power of our agency within it. To the contrary: upon falling ill, we are thrust into an alien world and stripped of our agency. Glaring florescent lights, gleaming metal, white walls, forms, questions, tests, uncertain waiting, endless submissions when the world has already taken away any sense of control – what Barbara Ehrenreich in her book Natural Causes (2018) calls ‘rituals of humiliation’. When physicians handwrote prescriptions, their writing was notoriously illegible, symbolic of the fact that there was no need for transparency. Faceless corporations manufacture medicines using inscrutable methods. The medicine works, or doesn’t, based on biological principles that most of us only vaguely understand. Even the names sound alien – Abraxane, Taxotere, Xeloda, Thioplex, Gemzar – and none is available without a costly prescription.

At one time, magico-religious narratives and rituals addressed concerns that lie beyond the purview of medical science. As the sphere of religion’s authority shrinks, it has become increasingly difficult to give explicitly supernatural – or, if one prefers, existential – answers to the Why me? and What can be done? questions of illness. The paradigm of scientific naturalism in which modern medicine operates can’t fill the gap, so people respond to the existential betrayal of illness by looking elsewhere. This is where nature and naturalness come in.

In an important sense, ‘natural’ is simply shorthand for something like ‘outside of the dominant system’, which explains the perplexing variety of interventions in the Purist list, many technological, and drawn from a hodgepodge of metaphysical systems. The category ‘natural healing’ isn’t meant to demarcate a set of interventions chosen according to systematic criteria. Rather, it has emerged organically out of basic human needs, gathering together anything that can help suffering people address the pain that transcends biology.

As answers to Kleinman’s questions (Why me? and What can be done?), the PEMF machine, the vitamin supplements, the bleach bath, the energy healing and the Ayurvedic food all make sense. They grant patients agency. All are available to a layperson. The explanations make sense, or seem to, without any deep understanding of biology or chemistry. Breathing exercises help us direct ‘the flow of vibratory life energy’. Detoxification purifies the body of dangerous elements. Vitamins replenish deficiencies and boost the immune system. Like prayer, and unlike chemotherapy or vaccines, they address not a specific illness but any kind of current or possible suffering. What can be done? A great deal, it turns out, and it is within your control. You can make your body whole, balanced, purified and renewed with ingredients from your pantry and an energy machine available on eBay. No insurance or prescription is necessary.

Metaphysically, ‘natural healing’ is not internally coherent. Yet the word and idea ‘natural’ is irreplaceable because it contains a satisfying existential answer to Why me? Most ancient medical systems see the well-ordered human body as a microcosm of a larger, harmoniously ordered whole. The balance of yin and yang that makes human health possible mirrors the natural cosmic balance that governs the health of nations and the natural world. Suffering is always a result of departing from the natural order of things. It can be avoided by realigning oneself with an order that’s at once physical and metaphysical. Sin might no longer be a plausible cause of illness, but unnatural activity – sin, secularised – still is.

The human body as a site of unnatural harm is particularly compelling as we constantly confront the harm that technology inflicts on the natural world. Animal species, millions of years in the making, gone in a geological blink. Ancient waterways clouded with waste. The land disembowelled and burned, the fumes heating the planet. These tragedies – the product of technology deployed on a massive scale – threaten the body of the Earth and individual human bodies alike. Millions are sickened by living near factories, industrial, agricultural and other emblems of unnatural modernity. The ‘Western medicine’ rejected by natural healing is a synecdoche for the modern Western world.

Being invited to tell your story is an essential part of the healing process

COVID-19 is easily fitted into the explanatory framework of natural systems corrupted by unnatural modernity. Pandemics are our punishment for exploiting nature: cutting down forests where bats make their homes, trafficking in exotic wildlife, factory farming. Presented with this binary, why not fight the resulting illness with something natural, instead of using ‘unnatural’ approaches that owe their existence to the very system that caused the problem to begin with. Why us? Because we have violated natural systems. What can be done? Restore ourselves, and the world, through restoring everything to its natural balance.

Existential explanation, a route to salvation for humanity and its home – this is why the mistranslation of Hippocrates must include the word thy, as if plucked directly from the King James Bible. This is why Cristina Cuomo’s magazine is called Purist. Natural healing affirms the existence of a benevolent divine force that seeks to promote life and safeguard our health. When faced with a health crisis, we might require what the bioethicist Insoo Hyun calls ‘therapeutic hope’, medical interventions that, in addition to promising efficacy, also create meaning.

This lens, not ‘naturalness’, is the best way to see Purist’s COVID-19 protocol, which its founder credits to the naturopath Linda Lancaster. Lancaster founded Light Harmonics, a healing system ‘based on the philosophies of Yoga, Ayurveda, Anthroposophy, TCM, Naturopathy and Homeopathy’. Lancaster and Light Harmonics teach patients to ‘access and care for’ their body’s ‘vital force to heal … [to] switch on our body’s ability to stay well in a world of challenging forces and help our body to heal when we are sick. This force exists within everyone, no matter their age, current health concerns, or predispositions.’

Medical ethics dictate that therapeutic hope cannot veer into false hope or falsehood, which means that medical science should remain epistemologically constrained by honesty about the limits of its power and the answers it can give. Healers such as Lancaster aren’t bound by those constraints. But as Kleinman and other physicians have shown, when people fall ill, or fear falling ill, religious leaders and natural healers – who, today, are often one and the same – need not be their best recourse for the existential travails of illness and medical treatment. When reforming medicine, cost and efficacy mustn’t be the primary criteria, even if they are the most easily quantified. Instead, we should focus more on the humanity of the patients. Physicians need to be given time to listen to their patients – not necessarily because that will allow them to identify and cure illnesses more easily, but because being invited to tell your story is an essential part of the healing process. Mainstream medicine needn’t swap scientific naturalism for natural medicine’s contradictory grab bag of anti-establishment inclusivity. But it would do well to address the need for metaphysical consolation that explains why patients seek out natural medicine despite those contradictions.

To read more about the psychological challenges of living, visit Aeon’s sister site, Psyche, a new digital magazine that illuminates the human condition through psychological knowhow, philosophical understanding and artistic insight.