In late December 1791, Rose Mainville, a 17-year-old French girl, made a horrifying discovery. She found her name, address and physical description in a pornographic book advertising itself as a detailed guide to the sex workers of Paris. Ashamed, humiliated and terrified at the thought of being confronted by her family, friends and neighbours, she took her own life by drinking a bottle of nitric acid.

The entry for Rose Mainville in the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris (1791-92). Courtesy the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Amid the tumult of the early years of the French Revolution, the tragic story of Mainville’s suicide might easily have been forgotten. Instead, it became a cause célèbre, with newspapers across Paris reporting on the story. Mainville was cast as an honest, hard-working street vendor who had been the victim of malicious slander. Two Parisian theatre companies even staged a dramatisation of her story in order to rally public opinion in her defence. Journalists called for the pornographic book to be banned, and for the book’s anonymous author to be punished. In fact, they argued, many other libellous books and pamphlets, offering similarly revealing information, should be forbidden. A private person should not fear exposure in the public sphere.

Illustration from the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris (1791-92). Courtesy the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

If Mainville was alive today, we would call her exposure ‘doxxing’: publishing or publicising an individual’s name, address or employment information, often with malicious intent, so that they are ‘unmasked’ or ‘shamed’. It wasn’t illegal for the anonymous author to include her name and address in his pornographic book. Although she was harmed by this identification and exposure, she had no recourse to justice, nor could she demand a retraction. Mainville’s story shows us how difficult it can be for victims to find justice in a society grappling with the balance between free speech and the right to privacy. All societies decide where this balance lies. In Revolutionary Paris, privacy was a privilege that only the elite and powerful could enjoy.

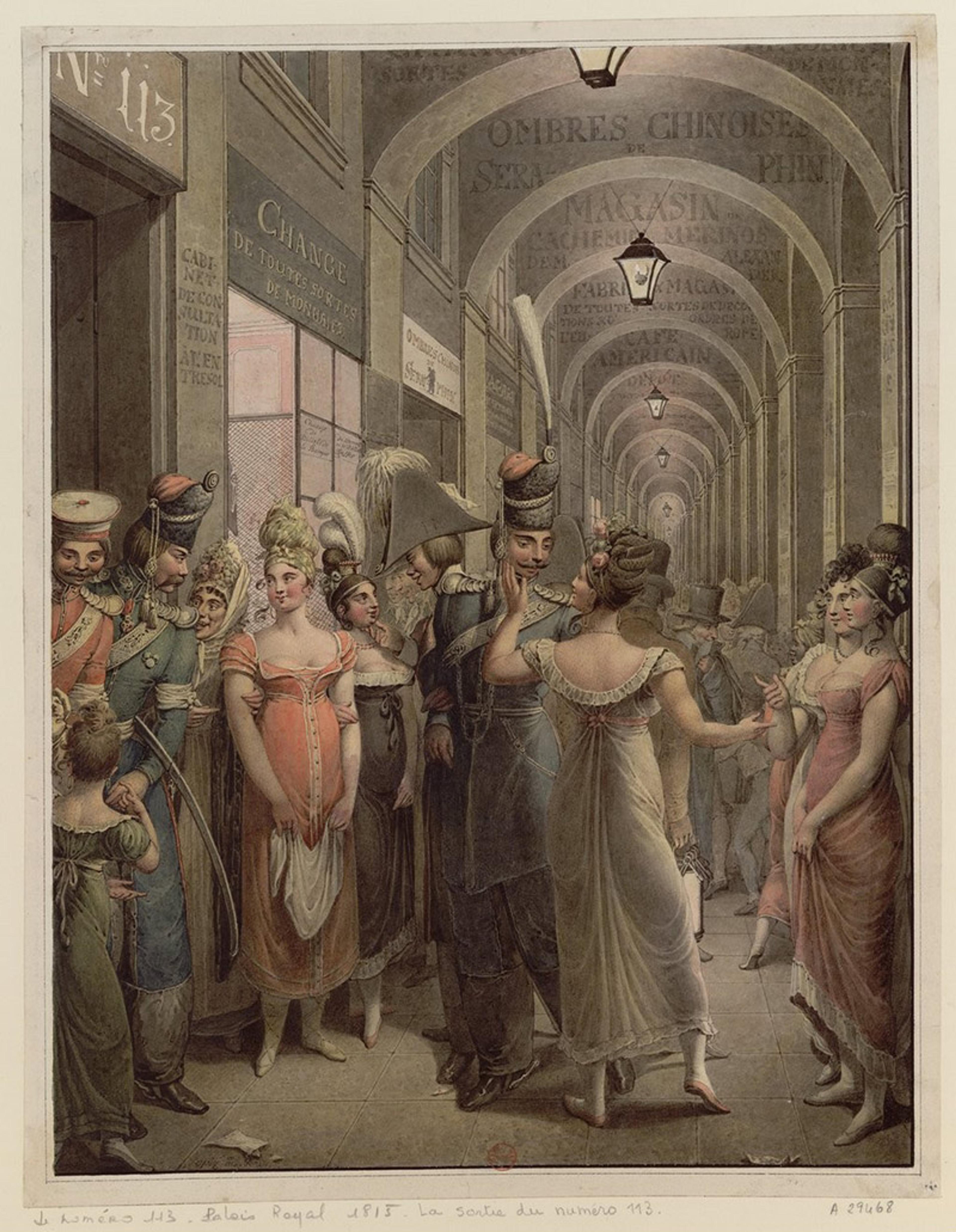

Mainville lived and worked in and around the Palais-Royal, a site renowned for its association with both liberty and licentiousness. Initially built in the 1630s as a palace for Cardinal Richelieu, the Palais-Royal had a succession of royal owners, ultimately ending up in the hands of the Duke of Orléans, a cousin of King Louis XVI. In the 1780s, the duke dramatically expanded the Palais, adding new six-storey apartment buildings with retail space, and enclosing the palace’s extensive gardens on three sides. This commercial venture was a success, and the Palais-Royal regularly attracted huge crowds to its shops, cafés, theatre and public gardens. Crucially, because it was owned by a member of the royal family, the Palais-Royal lay outside the jurisdiction of the Paris police. This meant that it was a safe space for radical or controversial political speech. In fact, in July 1789, the protests that led to the storming of the Bastille had begun in the gardens of the Palais-Royal.

But the Palais harboured other forms of illicit activity: gambling, stock-jobbing, the sale of pornographic materials. It was also a space for sex work. In the arcades and gardens of the Palais, sex workers walked, talked and mingled with wealthy shoppers, middle-class theatre-goers, and street vendors like Rose Mainville.

The pornographic book in which her name appeared – called the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris – purported to be a comprehensive guide to the sex workers who laboured in the gardens and brothels of the Palais-Royal. Such books were not uncommon in the late 18th century. Almanacs, reference books and city directories were a popular genre, and it is perhaps no surprise that some authors saw an opportunity to parody those works and give them a salacious twist. The author of the Almanach claimed to be inspired by Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies, a well-known London directory of sex workers published between 1757 and 1795.

The book provided its reader with a ‘portable harem’, transforming him into a ‘real Sultan’

Like other guides published in Paris during the early years of the French Revolution, the Almanach followed an established framework: each entry contained a name, address, physical description, some titillating details about sex acts, and the cost required to secure the woman’s labour. A sex worker named Madame Sevigny was described as having ‘a nice smile, a big mouth; [and] beautiful teeth’. She was the ‘widow of a painter’ and had ‘formerly [been] a chambermaid’. Madame Pérignon was known for ‘usually tak[ing] the top’ while Madame Laurent ‘speaks her mind’. Mainville herself had a ‘charming figure, lily & rose complexion, [and] beautiful eyes’ as well as a ‘cute foot’ and ‘shapely leg & thigh’. At only ‘17 years old’, the author boasted, Mainville was a ‘tasty little bourgeois’.

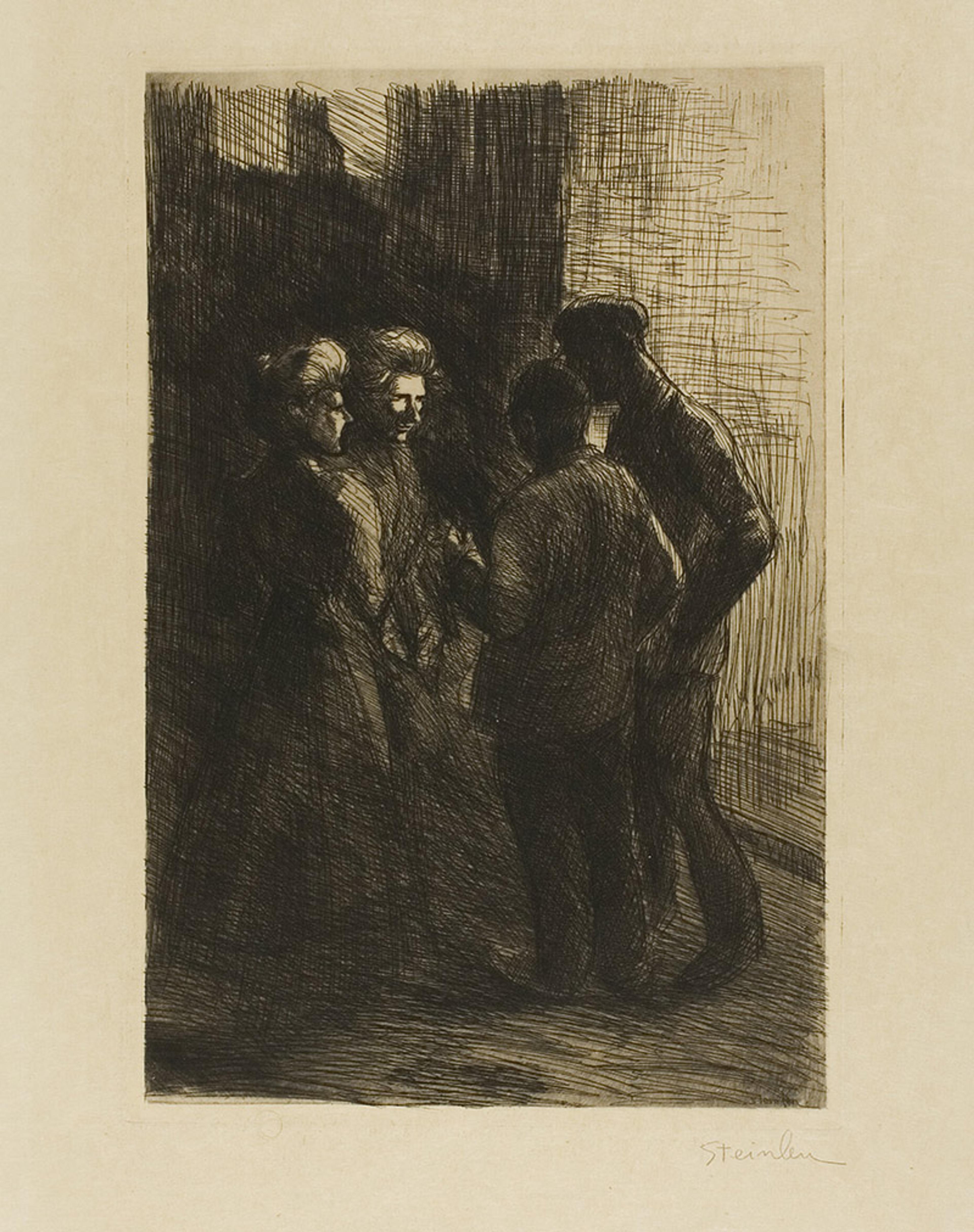

Two Women of the Street and Their Companions (1898) by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

The entries in the Almanach were sexually explicit and full of jokes and innuendo. Whether or not the book actually served as a practical guide, it was definitely used for entertainment, for masturbation as much as assignation. Attempting a pun about ships and sailing, the author sneered that Madame Dugazon was a ‘large & beautiful frigate’ who, when younger, had been ‘an excellent sailboat, but today she is leaking everywhere. – To plug all the holes … 600 livres.’ If a man wanted to have sex with Adeline, rumoured to be the mistress of a priest, he had to pay 500 livres ‘to say a mass at her chapel’. Even the Revolution and its ideals were subject to ridicule in the Almanach. Madame Laurent was ‘very constitutional’ and ‘knows the rights of man by heart’. This woman was, the author laughed, a true citoyenne, for ‘she admits into her central committee two deputies every day’ and would accept only the Revolutionary government’s paper money as payment.

All of this information, the Almanach argued, served the public interest. The author claimed that his book was most useful for foreigners and provincial visitors, but also could be a valuable resource for Parisian men. Drawing upon eroticising and orientalising stereotypes, the book claimed to provide its reader with a ‘portable harem’, transforming him from a ‘simple citizen’ into a ‘real Sultan’. The author of a rival pamphlet, the Tarif des filles du Palais-Royal, described his own work as ‘an act of patriotism’, explaining that its purpose was to provide information about the true cost of sexual services so as to prevent price gouging.

It may seem surprising that these guides, filled with misogynist humour, dirty puns and political satire, were printed at all. The French monarchy did, in fact, impose strict censorship rules on all printed materials. This did not stop libellous, rude or sexually explicit materials from circulating; it just meant that they often had to be printed outside of France, smuggled in, and sold in secret. Before the revolution, it would have been possible to buy a pornographic work like the Almanach, but only by asking a discreet bookseller about materials kept off-book and under the counter.

But at the start of the revolution, the monarchy was forced to abandon its censorship rules. The Revolutionary government, filled with new ideas about free speech, made it possible for any kind of radical work to be published without oversight. Thousands and thousands of books, pamphlets and newspapers were published and read. While the majority of these works were political, the end of censorship also massively increased the availability and visibility of illicit texts of any kind, including pornographic ones like the Almanach. By 1791, these works were being hawked across the city and under the arcades of the Palais-Royal where Mainville worked.

The new Revolutionary government understood that its embrace of the principles of freedom of speech and press had consequences. It was now possible to slander, lie and falsify information in print. In an attempt to put a stop to truly malicious libel, the new French equivalent of the Bill of Rights, the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et et du citoyen, asserted that ‘the free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious rights.’ But it also warned that citizens ‘shall be responsible for abuses of this freedom’. This meant that authors were free to publish what they wished, but that they could be punished after the fact if their works violated laws prohibiting false and malicious statements about public or private individuals.

Actresses made up a significant majority of the entries in the Almanach

In the wake of Mainville’s suicide, her defenders in the press argued that the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris had broken these Revolutionary libel laws, and they called for the prosecution of its anonymous author. However, critics of the Almanach were not concerned about the privacy of sex workers, because, as one journalist remarked, these women ‘want nothing more than to be known’. Instead, they worried that sexual slander was damaging to family relationships and, by extension, to social hierarchies and the state. Amid bitterly contentious revolutionary politics in the early 1790s, sexual slander was increasingly used as a political weapon against politicians and public officials. This libellous speech not only undermined public trust in government but also threatened to spill over into disputes between private citizens. This appeared to be the case in Mainville’s tragic tale.

Journalists commenting on her story compared it with the publication of the infamous Nouvelle assemblée des notables cocus du royaume, a list of well-known men who had been cuckolded, printed alongside the names of the people who had allegedly had sex with their wives. If otherwise respectable private households were becoming victims of sexual slander, the Revolutionaries decided, then more censorship was, regrettably, necessary. One typical article called upon the mayor of Paris, Jérôme Pétion, to suppress the Almanach and books like it, citing Mainville’s death as evidence of the fact that such publications ‘cause[d] great disorders inside families’. Another journalist declared the book a ‘disastrous calamity’ for the state and suggested that, however much one supported freedom of the press, it was clear that ‘the law had to pronounce serious penalties against those who seek to damage the reputation of citizens.’

Prostitution at the Palais-Royal in 1815 by Georg Emanuel Opiz. Courtesy the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Protests against Mainville’s ‘doxxing’ didn’t appear just in print. Within a month of her death, two theatre companies each brought a different version of her story to the stage. The plays dramatised and no doubt embellished her story, including changing her name to Gertrude. Gertrude, ou le Suicide du 28 Décembre debuted on 25 January 1792 and was performed at least 11 times in the span of two months, while Le Suicide du 28 Décembre 1791, ou les Effets de la calomnie debuted a week later and was performed at least 10 times.

The first to appear, Gertrude, was performed at the Théâtre Montansier, located within the Palais-Royal itself, and was written by a playwright named Joseph Aude who claimed to be personally acquainted with the details of the incident. In Aude’s version of the story, Gertrude Mainville was an honest, hardworking young woman, soon to marry her sweetheart. The play had two villains: Gertrude’s jealous ex-boyfriend, who wrote the Almanach; and Gertrude’s female rival, who sent a copy of the book to Gertrude’s mother so as to intentionally embarrass her in front of her family. Gertrude is driven to despair at the shame and humiliation of these revelations, and is tortured by the anticipated collapse of her engagement. Her head spinning, she swallows a bottle of nitric acid that she had purchased to produce an engraved portrait as a gift for her fiancé. Reviews of the play lauded the performance of the actress playing Gertrude, Anne-Françoise Boutet, known as Mademoiselle Mars. In fact, Mars’s premiere performance was so emotionally wrenching and her physical convulsions on stage so life-like that the audience was reportedly left disturbed and disquieted – so much so that Aude was forced to rewrite the ending of the play to make it more palatable to the public.

Mademoiselle Mars’s riveting yet upsetting portrayal of Gertrude was no doubt inspired by her own experience. Although it was never acknowledged by journalists commenting on the story or reviewing the play, Mademoiselle Mars was herself mentioned very prominently in the Almanach. And Mars was not alone: her two female co-stars in Gertrude at the Théâtre Montansier were also included in the book, as were two actresses at the Théâtre de Molière where Le Suicide du 28 Décembre 1791, ou les Effets de la calomnie was performed. In fact, actresses made up a significant majority of the entries in the Almanach.

The women represented in the Almanach were part of a large and diverse group of people who undertook sex work in Revolutionary Paris. Some women and men did this kind of labour all the time. Others performed occasional or seasonal sex work, soliciting when times were tight or when other jobs failed to come through. Some worked in an organised corps of workers; others worked alone. There were certainly moments of solidarity and mutual aid among sex workers but – just like in any type of employment – there were also rivalries and divisions. Sex workers competed with one another for clients, space and pay.

One particularly unified group of sex workers included women and men who worked in the theatres of Paris. Although not every performer did this kind of labour, it was a truism in the period that many of the people who worked on the stage also acted as companions, lovers or mistresses for the social, political and financial elite. These professionals were well compensated for their time, receiving cash payments, gifts of clothing or jewellery, rent for fashionable lodgings, or even valuable pensions from their patrons. Actresses like Mademoiselle Mars may have exchanged sex for money or gifts, but their relationships were imagined as ‘exclusive’, not in the sense that they were necessarily monogamous, but in that they were private and selective. Theatre professionals managed their sexual relationships carefully, cultivating an aura of erotic singularity, where potential patrons were vetted and assessed before being accepted. This was one reason why inclusion in the Almanach was so damaging. It was not just that elite sex workers did not like to be imagined as people who solicited passers-by in the gardens of the Palais-Royal; it was that they risked losing the air of fashionable rarity that might promise a more secure and lasting livelihood. They definitely did not want men showing up at their homes uninvited, clutching a copy of the Almanach and its advertised sum.

Mainville was not an actress – her name does not appear in any of the period’s theatre guides – but it is more difficult to know how she made her living or why she was listed in the Almanach. Although the two theatrical performances and the newspaper articles about her death consistently portrayed her as a street vendor, other evidence is less conclusive. Some elements of her story suspiciously resemble well-worn narrative tropes of the late 18th century. At least one journalist, even as he protested her innocence, described Mainville as ‘a sausage seller’ at the Palais-Royal, perhaps a not-so-subtle wink at male readers keenly aware of the location’s reputation as a centre of sex work in Paris. It is also important to note that another guide to sex work at the Palais-Royal, the Tarif des filles du Palais-Royal, most likely published in 1790, listed a woman named ‘Mainville’ at an address similar to the one in the Almanach. Perhaps Rose Mainville was a sex-worker at the Palais. Perhaps she was only a street vendor there. But this ambiguity is not surprising, especially given the diversity of sex workers in Paris.

The law permitted the author of the Almanach to protect their anonymity even as victims lost their own

No matter how she supported herself, Mainville certainly had something in common with Mademoiselle Mars and the other actresses listed in the Almanach: her reputation, her livelihood and her connections with family and friends may have been threatened when she was revealed as a ‘prostitute’ in print, but the legal system afforded little recourse. Absent prepublication censorship, anyone could publish anything, whether it was a controversial political opinion or a sexual slander. New Revolutionary free speech laws did allow for civil and criminal prosecution of authors who wrote slanderous works, but only after they appeared in print – in other words, after the damage had already been done. And even these legal remedies were of limited use. Prosecution was difficult in cases where books or pamphlets did not reveal their authors or publishers.

In the case of the Almanach, Aude, the playwright of Gertrude, claimed to know the true identity of the author, but there is no evidence that this person ever faced charges. Criminal or civil lawsuits would have been expensive and would have invited additional unwelcome public scrutiny of women who had already suffered damaging exposure. In its practical application, the law permitted the author of the Almanach to protect their anonymity even as victims lost their own, their private lives and livelihoods exposed to a voyeuristic and potentially dangerous public.

Technically in possession of legal rights but deprived of any realistic ability to exercise them, many women who appeared in the infamous pages of the Almanach would have felt as powerless as Mainville. But Mademoiselle Mars and the other actresses did have one very potent weapon at their disposal: the stage. By taking up Mainville’s cause and reimagining her story in front of their audiences, they crafted a compelling and sympathetic narrative designed to undermine and publicly shame the author of the Almanach. This approach, too, had limitations. Given the public’s hostility towards sex work, Mars and her fellow actors had to cast Mainville as an ‘honest’ and ‘innocent’ young woman unfairly slandered in print. To describe her as a sex worker, even on the stage, would have invited criticism of her story.

This story suggests some valuable lessons that might inform how we think about more recent cases of doxxing of sex workers, who have been targeted because their labour supposedly blurs the line between public and private, what is shared and what is kept separate, what is allowable as a freedom of the press and what constitutes a gross invasion of privacy. Doxxing is unethical as well as, in some cases, illegal, but its victims have found that they cannot rely on the law to protect them. Neither the government nor social media companies take the problem seriously enough and, as in the case of the Almanach, by the time private information is removed from public view, significant damage has already been done.

Although there is a much greater degree of social acceptance of sex work today than there was in the late 18th century, gaining broad public sympathy for victims of doxxing is often still predicated on finding the right sort of victim. In December 2020, The New York Post came under fire when one of its reporters doxxed a paramedic who supplemented her income through online sex work, revealing her name and photos in a piece that they ran on emergency medical workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The backlash to the article was in large part fuelled by the fact that the doxxing victim was a medical first-responder during a pandemic. Other sex workers rarely gain this level of support.

The underlying problems of doxxing lie in misogyny and our refusal to accept that, though some of their work is public-facing, sex workers have the right to privacy and personal safety. The understandable tendency to rally around sympathetic victims can stymie real change, with the majority of victims left ignored, and underlying, large-scale social and cultural problems left unaddressed. The solution is to normalise sex work, respect sex workers, and advocate for privacy protections for all.