Listen to this essay

What does government govern? What, in other words, is government the government of? The answer – at least in the West – has shifted over time. In the age of religion, kings and queens ruled over souls, preparing them for the divine beyond. After the Enlightenment, the soul gave way to the mind as the focus of governance. By the late 18th century, the target had shifted again. In the first volume of The History of Sexuality (1976), the philosopher Michel Foucault observed that, as the 19th century approached, government was turning its gaze to the body itself. Biological life was no longer incidental to politics: life and death, sickness and health became objects of management, control and regulation. Foucault called this new regime ‘biopolitics’ or ‘biopower’.

Across the centuries since, the government of bodies has grown only more visible – and more contested. So much of our politics now revolves around managing them. We see it in battles over trans participation in sports and access to abortion, the furore over Elon Musk’s Neuralink brain implants, and the push to regulate red dye in food. Even an issue as seemingly distant as school funding is, at bottom, a struggle over the body; that makes sense, since research shows how profoundly the environment impacts brain development and neuroplasticity from childhood all the way through early adulthood. When we talk about school budgets, we’re talking about the kinds of brains (and bodies) we want to produce. When we worry about AI in classrooms, we’re worrying that students may never form the pathways of critical thought and focus they need.

The reigning biopolitical disputes hinge on deceptively simple questions: what is the body for? What should we do with it? Are there levels of biology where a difference of degree becomes a difference of kind? If a human body changes (or is changed) beyond a certain point, does it stop being an altered human body and become, instead, something else?

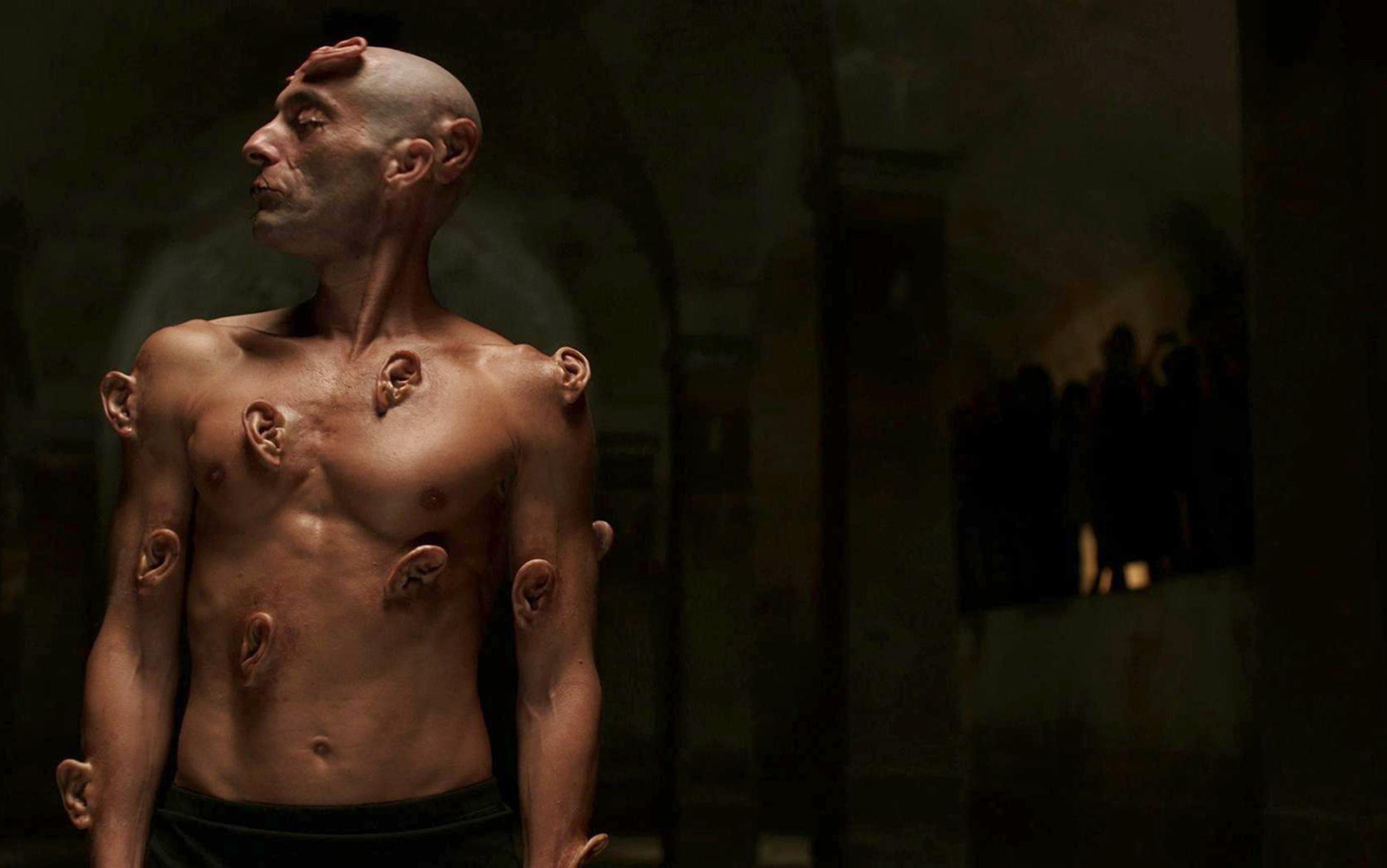

There’s no shortage of modern artists and thinkers wrestling with these questions. The choreographer Meg Stuart pushes bodies to extremes of movement; the multimedia artist ORLAN and the transgender artist Cassils use performance to test the boundaries of flesh and identity; another performance artist, Stelarc, stages the body as machine, grafted with prosthetics. Patricia Piccinini’s sculptures imagine hybrid anatomies, while the films of Julia Ducournau – director of the body horror Titane (2021) – and Claire Denis probe bodily desire and transformation. In scholarship, Yuval Noah Harari tracks the future of the human species, Kate Crawford critiques the bodily costs of AI, and Paul B Preciado theorises on gender transition and pharmacopolitics.

And yet, few voices have been as persistent – or as transformative – as David Cronenberg’s. Since the 1970s, he has been cinema’s great anatomist, staging dramas of growth, decay and mutation. Over the decades, his vision has shifted: from a romantic belief that altered bodies deserve celebration, to a more careful insistence that people should be free to alter themselves only if they choose. The arc feels natural, but it is also urgent right now. At a moment when the fight over bodies threads through disputes on everything from vaccines to elder care, Cronenberg offers a framework we need: a way to affirm bodily autonomy without stoking the panic that casts every transformed body as a threat. His cinema points toward a politics of protection – one that secures the vulnerable while refusing to weaponise their difference, and that shows how the defence of bodies can be a form of solidarity rather than a spark for fear.

‘Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.’ That’s a quote often, though wrongly, attributed to Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 (1961). But it might as well be the theme of Cronenberg’s cult classic Videodrome (1983). The film’s ‘they’ are the menacing minds at Spectacular Optical – a supposed global corporate citizen whose public face is the production of reading glasses for the developing world, while its true business is weapons technology. The company is run by Barry Convex, who tells the hapless protagonist Max Renn (James Woods) not about missiles, but about another product altogether: Videodrome.

The name refers to a top-secret video stream picked up by pirate TV stations like the one Max runs in Toronto – Civic-TV. Part-snuff, part-hardcore porn and entirely unburdened by sentiment, Videodrome delivers in brutal closeup the sadomasochistic torture and murder of its ‘contestants’. Unbothered by the violence and desperate to attract more audience to his flagging station, Max resolves to license Videodrome for Civic-TV. Max is hardly a prude. Reviewing clips of erotica that his production assistant Harlan recommends, Max responds only that ‘There’s something too soft about it.’ He wants something ‘tough’ enough to ‘break through’ and finds it in Videodrome. The world may be a ‘shithole’, says Max, but at least TV still thrills.

Like the film’s audience, Max is surprised to discover such unhinged, Dionysian material produced by a weapons manufacturer. But ultimately the logic becomes clear: Convex reveals himself to be a scolding emblem of the emergent Moral Majority. He can’t understand why anyone would watch a ‘scum show’ like Videodrome. So, he discloses to Max, he produces it precisely to rid the earth of such people. Videodrome optically triggers the growth of a malignant brain tumour in people who watch it repeatedly. (Hence the use of ‘drome’ in the game’s name, from the Greek dromos, meaning ‘track’ – later folded into the medical term prodromal, for the early symptoms of a disease.)

Sex and violence, to his mind, are crucial emblems of liberal society, and essential elements of democracy itself

Echoing both the recently elected Ronald Reagan and his allies, Convex bemoans that ‘North America’s getting soft, patrón, and the rest of the world is getting tough. Very, very tough … we’re going to have to be pure and direct and strong, if we’re going to survive them.’ Purveyors of smut like Max, Convex complains, are ‘rotting us away from the inside’ with their morally bankrupt entertainments. A foot soldier on behalf of a larger biopolitical system in the Foucauldian sense, Convex thus deploys Videodrome to destroy the weak and create a standing army of able bodies ready to serve political aims.

Convex’s murderous speculations horrify Max. Yet, for audiences in 1983, it wasn’t hard to see the dark convergence between Convex’s ‘strong’ moral virtue and the genocidal politics of the day, targeting the vulnerable like gay men, heroin addicts and others who just needed help. The wages of ‘sin’ for both Convex and his real-world analogues in the evangelical, fundamentalist movements riding high when the film was made were paid in death; the government of bodies as well as souls was on the rise, on the screen, in the streets, all around.

Max’s discovery of this repellent politics radicalises him, pushing him beyond the ambivalence of the film’s first half. If at first Max found purely economic value in the lurid broadcasts, he now becomes evangelical about their ethical and political value. Sex and violence, to his mind, are crucial emblems of liberal society, consummations of the personal imperative and essential elements of democracy itself.

He goes so far as to reconceptualise the tumour not as a malignancy, but as a new form of bodily potential. ‘Long live the new flesh!’ becomes his mantra, a cry echoing in the real world far beyond the film. By the 1990s, after all, gay men were forming ‘bug chasing’ subcultures in the wake of antiretroviral therapies that rendered HIV a manageable, largely asymptomatic condition. These viral experimenters reimagined HIV as a means of inviting a shrine to the dead within their very cells. In this way, HIV functioned as the serological analogue of a votive candle or in memoriam tattoo. Max’s heroic reconfiguration of the tumour still calls across generations, not just to gay men, but to trans communities and even disabled people now tapping implants and other cyborg tech.

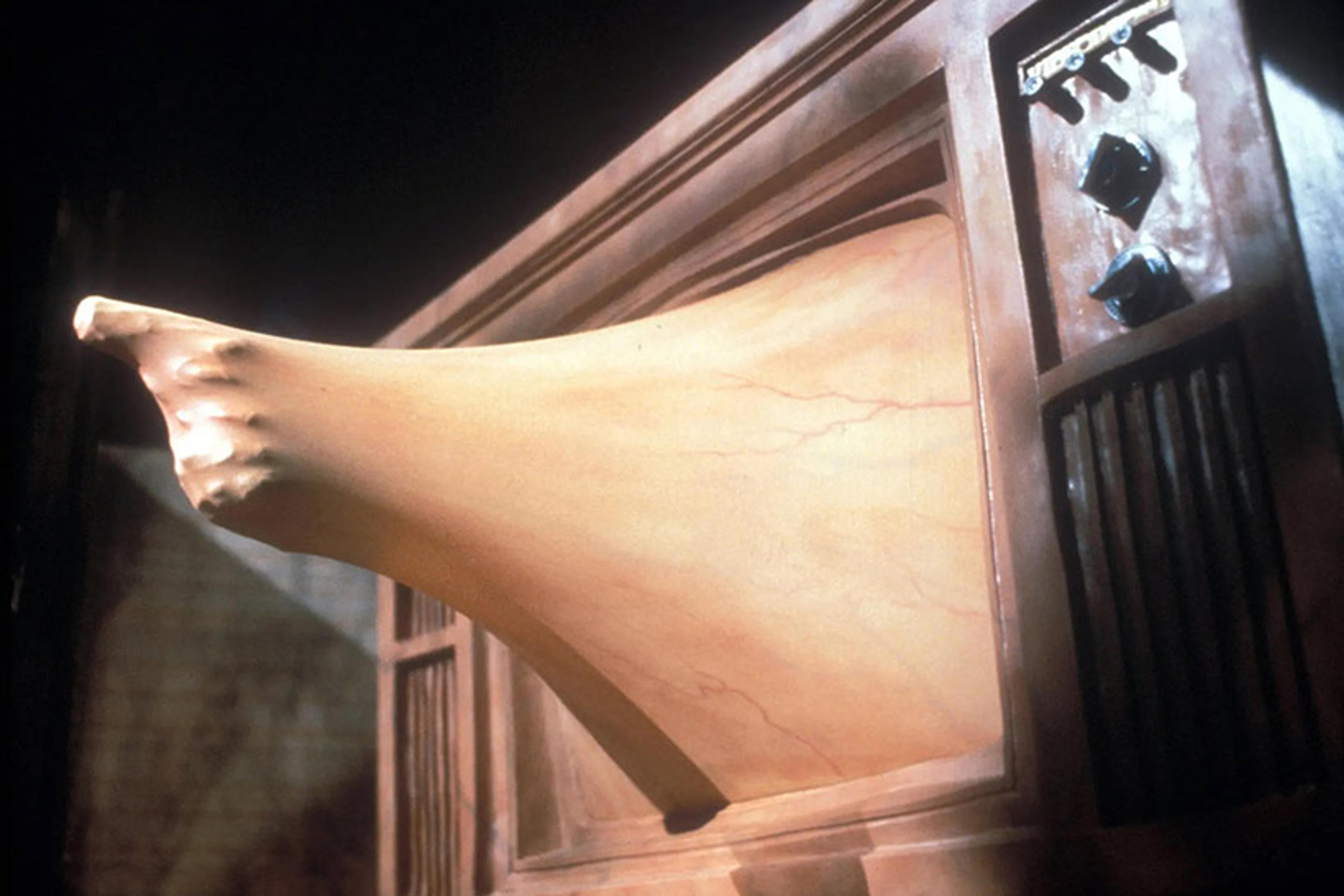

But if the resonance stretched outward, Cronenberg kept grounding it in the visceral images of his film. By the end of Videodrome, Max’s TV screen ripples into a living membrane, a hand straining through and clawing violently toward him. His abdomen yawns open like a wound, revealing a cavity where a pistol waits in the dark.

From Videodrome (1983)

From Videodrome (1983)

With dark humour, the scene makes its point: video doesn’t just influence minds, it cuts into flesh. Videodrome is an aggressive, even phallic force – but Max’s vaginal wound turns him, and the resistance he embodies, into a strange feminist figure. Cronenberg riffs on the vagina dentata – the myth of the toothed vagina – aligning pornographic liberation with the woman who fights back. By the finale, when Max’s stomach bites off the hand of his betrayer, Harlan, Videodrome leaves no doubt about its allegiances. Convex and Spectacular Optical embody a reactionary politics: militarism, puritanism, the fantasy of bodies hardened for war. Against them stands Max, whose radical – and, through his wounds, feminist – politics insist that bodies can be more than weapons. They can mutate, sprout new organs, expand toward pleasure. Max is the film’s hero, but so is the new flesh he champions. Bodies, the film insists, should change, should open, should invite the world in.

The clarity of Cronenberg’s stance in Videodrome is striking when set against the two films he made just before it: The Brood (1979) and Scanners (1981). In The Brood, the villain is a psychotherapist who urges patients to expel their traumas through a process he calls ‘psychoplasmics’, producing growths and deformities as a kind of physical exorcism. But unlike in Videodrome, mutation here brings only pain and regression. The new flesh is no liberation – only pathology.

Two years later, in Scanners, Cronenberg pushed further into the politics of bodily change. The film is set against ConSec, a shadowy military-industrial conglomerate attempting to harness humans who have telepathic and telekinetic powers. ConSec wants to weaponise them for surveillance and war. At first, the story seems to pit one such psychic or ‘scanner’, the rebel Darryl Revok, against ConSec, but his aims prove no less authoritarian. The real moral centre is Cameron Vale, another scanner, who ultimately decides that the mutations are too dangerous to persist. By the end, Vale gets his wish: the scanners must be stopped.

Compared with The Brood, Scanners complicates the politics of mutation: gone is the clear-cut villain of the mad scientist, and Vale himself embodies the power he condemns. Yet, despite this nuance, the film still portrays mutation as affliction, not possibility. Only with Videodrome does Cronenberg’s position crystallise, offering a categorical break from his earlier ambivalence. Here, at last, mutation becomes emancipation.

Released four decades later, Crimes of the Future (2022) finds Cronenberg returning to nearly the same themes and questions. Set in, well, the future, it centres on Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen), a man whose body spontaneously grows novel organs. Saul earns a living by staging public events in which his assistant Caprice (Léa Seydoux) surgically removes these organs in front of a live audience. Saul and Caprice are pursued by two rival groups. On one side are representatives of the National Organ Registry, whose goal is to maintain an active catalogue and archive of these growths for research. On the other side is a rogue cell of outlaws – radical evolutionists – who are actively trying to accelerate changes to the human body outside governmental control. Their chief aim is to induce a new kind of digestive system that can process synthetic chemicals and plastic-looking bars made of toxic waste. They have succeeded in at least one case: a boy named Brecken, son of the group’s leader, Lang, can eat the plastic bars – until he’s murdered by his mother, who believes her child (perhaps rightly) to be a monster.

The evolutionists want Saul and Caprice to leverage their wide audience and perform a public autopsy on Brecken’s body so the world can see that their evolutionary goals have been realised. Saul and Caprice agree. But upon beginning the autopsy, they discover that the boy’s body has been altered: the mutant organs are gone, and a traditional digestive system has been implanted into his corpse. For Saul, the implication is clear: someone from the government has intervened to sabotage the evidence of evolutionary change, undercutting the evolutionists’ claims. Disenchanted with what he sees as reactionary governmental overreach, Saul seems to throw in his lot with the rogue evolutionists. The film’s final scene shows Saul fitted into his ‘Breakfaster’ – a cybernetic chair he has used throughout the film.

From Crimes of the Future (2022). Courtesy Serendipity Point Films

The chair jars and shakes his upper body to help him digest food. In this last sequence, Saul asks Caprice to feed him one of the toxic bars. As he takes a bite, a closeup shows a tear falling from his eye. The chair falls still, and the film cuts to credits.

Saul has grown new organs in political sympathy, and now digests the toxic bar comfortably

So, what does this enigmatic conclusion mean for the film – and what does it say about Cronenberg’s latest views on the politics of bodily modification?

The first question is easier. Like Videodrome, Crimes casts a jaundiced eye on the view that bodies should be constrained, that change should be reversed. While the bureaucrats present themselves performing an academic task – cataloguing new organs – they are clearly allied with secret police willing to use espionage and infiltration to mutilate a dead child’s corpse.

What’s less clear is whether Saul’s choice to eat the plastic means he has joined the radicals who want to accelerate human evolution. One reading says yes: the stillness of the Breakfaster suggests that Saul has grown new organs in political sympathy, and now digests the toxic bar comfortably.

But another reading resists that optimism. Saul Tenser’s first name evokes one of Western mythology’s most famous conversions: the Hebrew jurist Saul struck by revelation on the road to Damascus, who became Paul, disciple of Christ. Yet Cronenberg’s character is not Paul. He remains Saul – forever unconverted. His last name underscores the point: Tenser, a man still taut with strain. If the chair’s quieting seems to suggest relaxation, his Saul-ness and ongoing digestive tension undermine the idea that he has embraced the evolutionists. Just as likely, Saul’s decision to eat the bar is a kind of suicide. His tear marks not conversion but surrender: a choice to opt out entirely.

The 40 years between these films seem to have tempered Cronenberg’s bullishness on the politics of the new flesh. He remains repulsed by the reactionary forces that would rein in or reverse bodily change; he’s still hostile to biopolitical fantasies about the kinds of bodies governments might cultivate for their imperial, domestic or utopian ends. But that distrust no longer drives him to embrace the opposite camp – the revolutionaries. Put differently: opposing the enemies of the new flesh no longer means championing the new flesh itself. Crimes finds a Cronenberg who gestures toward solidarity between flesh both old and new.

It’s possible, of course, that this evolution reflects only the personal journey of one Canadian filmmaker. More interesting, though, is viewing Cronenberg’s body horror as a response to the cultural and political moment it emerged from. I make that wager – despite the uncertainties – because questions about bodies loom larger in politics today than they did in 1983. Not because the stakes are higher now; the HIV/AIDS crisis had already made those stakes brutally clear back then. But the arguments are more explicit now. Battles over abortion, trans rights, AI and neural implants dominate our political discourse. Cronenberg’s films offer a way to think about these struggles differently. His shifting vision gives us tools to reframe today’s fights over the body in more productive ways.

More precisely, Cronenberg now seems to model a view of bodily autonomy that values dignity and sovereignty over confrontation. Instead of celebrating the altered body in defiance, his later work suggests a quieter politics – less about pushing change, more about protecting space for it. Sceptical of how readily people accept difference, he invests not in promoting transformation outright but in securing zones of privacy where it can unfold. In this sense, his outlook is less progressive than liberal, in the broadest sense of those terms. Solidarity with the ‘new flesh’ no longer comes from demanding its arrival, but from portraying bodily change as natural, inevitable and quietly human.

Cronenberg’s cinema has always been about human bodies in transition

It would be entirely possible to depict Cronenberg’s transition between the early 1980s and today as yet another instance of a youthful radical becoming conservative with age – not so different, perhaps, from the Romantic trajectory of William Wordsworth. But I think that’s a facile read. Instead, the movement between Videodrome and Crimes documents a progressive becoming a liberal – and finding in that latter tradition a more effective way to derive freedom and dignity for progressivism’s traditional beneficiaries: those whose atypical bodies bear and bare, to borrow one of Cronenberg’s own titles, a history of violence. To up the ante, I speculate that Cronenberg has discovered the price of out-and-proud progressive advocacy. He has discovered how much people hate being told what to do, and how they will begrudge those on whose behalf their change (or is it ‘growth’?) is so feverishly induced. It could be that the most vulnerable among us find their greatest freedom and dignity when left to the civic protections of noninterference. What Cronenberg’s movies disclose is less a selling-out than the education of an idealist.

Of course, the example of HIV/AIDS proves how fragile and ineffective liberal politics can be. In the case of that plague, mere noninterference was not enough to save a generation of gay men from catastrophe. So, a charitable reading of Cronenberg would insist that it was that historical moment which generated the more confrontational politics assumed in Videodrome. But today’s moment demands something different. This is where the ongoing salience of trans rights comes into focus. In a way, Cronenberg’s cinema has always been about human bodies in transition. And Crimes, I think, stands as his letter to the court of public discourse – the accumulated wisdom of someone whose art has examined the altered body for nearly half a century now.

What’s not clear is if we’re prepared to listen.