In 2003, Edward Said wrote in the wake of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 and in the context of the United States’ war on terror that ‘humanism is the only, and, I would go so far as saying, the final, resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history.’ The moment, he felt, was ‘apocalyptic’, and the end was indeed near for him; he died of leukaemia later that year.

So why was it humanism that he held to so tightly as war and sickness cinched time’s horizon around him? Humanism, an intellectual and cultural movement that emerged in Renaissance Europe emphasising classical learning and affirming human potential, had been subject to decades of critique by the time Said was writing this. Among its many detractors were postcolonialists who argued that humanism’s elevation of a particular kind of human – Eurocentric, rational, empiricist, self-realising, secular and universal – had provided thin cover for the exploitation of large swaths of the world’s population.

But Said, one of the founders of postcolonial studies, hadn’t given up on the term, despite its imperialist entanglements. He imagined a humanism abused but not exhausted, an -ism more elastic and plural, more subject to critique and revision, and more acquainted with the limits of reason than many humanisms have historically been. Humanism, he argued, was more like an ‘exigent, resistant, intransigent art’ – an art that was not, for him, particularly triumphant. His humanism was defined by a ‘tragic flaw that is constitutive to it and cannot be removed’. It refused all final solutions to the irreconcilable, dialectical oppositions that are at the heart of human life – a refusal that ironically kept the world liveable and the future open.

At stake in his defence was not only the survival of the humanistic fields of study he had devoted his academic career to, but the survival, freedom and thriving of actual people, including those populations that humanisms had historically excluded. Various antihumanisms had gradually been eroding humanism’s stature within the academy, but it was humanism, he believed, with its positive ideas about liberty, learning and human agency – and not antihumanist deconstructions – that inspired people to resist unjust wars, military occupations, despotism and tyranny.

Humanism, however, fell further out of vogue in the two decades that followed. Humanities enrolments dropped dramatically at universities, and funding for departments like comparative literature, women’s studies, religion, and foreign languages got slashed. Increasingly, however, it wasn’t just the inadequacies of any -ism that were the problem. It was the subject at the heart of humanism that came under widespread attack: the human itself. Given that history could be read as a catalogue of human greed, blindness, exclusions and violence, the future seemed to belong to someone – or something – else. The humane in humanism seemed to be missing. Alternative ideologies like antihumanism, transhumanism, posthumanism and antinatalism seeped from the fringes into the mainstream, buoyed by their conviction that they might offer the planet or even the cosmos something more ethical, more humane even, than humans have ever been able to. Humanity’s time, perhaps, was simply up.

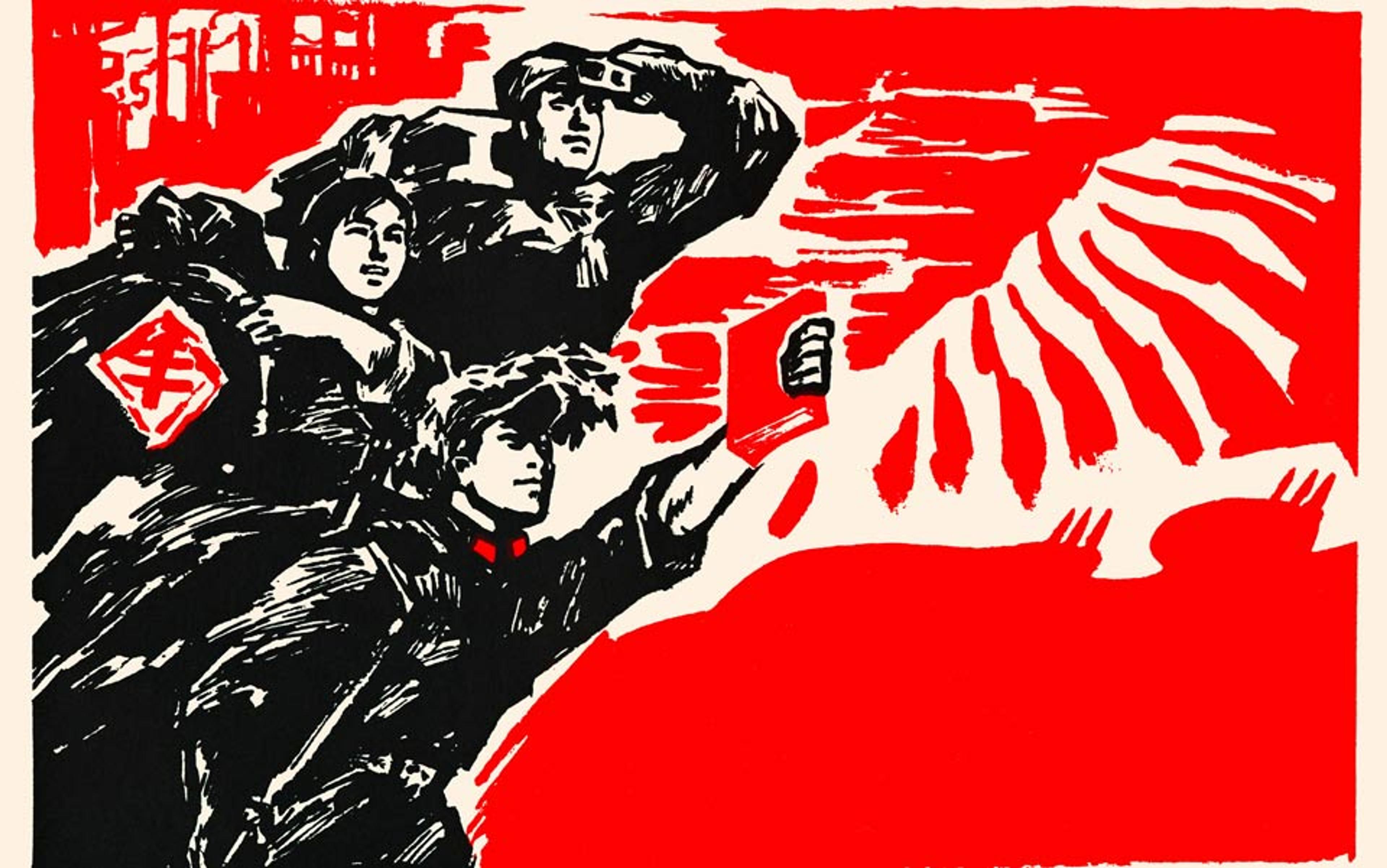

In his book The Revolt Against Humanity: Imagining a Future Without Us (2023), the American critic Adam Kirsch identifies the contested line between humanists and non-humanists as one of the defining faultlines of our political and cultural moment. The debates between them can feel merely semantic, the stuff of graduate seminars, but the revolt against humanity is likely to have major implications for our future, Kirsch argues, even if its prophecies about our imminent extinction don’t come true. ‘[D]isappointed prophecies,’ he writes, ‘have been responsible for some of the most important movements in history, from Christianity to Communism.’ Anyone committed to the prospect of a liveable future should pay close attention to what’s going on here.

This requires more than a passing glance; it demands the kind of careful, comparative critique that Said believed humanism inculcated in both its academic practitioners but also, importantly, in any concerned citizen of the world. To understand how a humanism like Said’s might be the only and final ‘resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history’, it is helpful to do some comparison readings.

I might have never put too much stock in a term like humanism if I had not read around in the transhumanist literature. I came to this work while researching a book on birth that explored the relationship between birth, death and the question of a human future. Does humanity have a future? Do we deserve one? What will that future look like? The answers to those questions will be determined by many forces – technological, economic, political, environmental and more – but also by how we experience and think about our own births and deaths. Despite large areas of convergence, humanists and transhumanists can end up with wildly different visions of our future, based on dramatically different understandings of birth and death, as one can see by comparing how a novelist (Toni Morrison) and a philosopher (Nick Bostrom) have explored these themes. Morrison offers us a prophetic celebration of Earthly, ongoing, biological generation and a future that allows for human freedom, while Bostrom points us toward a highly controlled surveillance world order, organised around a paranoid fear of human action, and oriented toward the pristine emptiness of outer space. Which future, we should ask ourselves, would we willingly choose?

Let’s look first at Morrison’s vision. Although she refused to identify as any ‘ist’, Morrison powerfully modelled the kind of tragic and yet affirmative humanism Said espoused. Her work, like his, bore witness to humanism’s failures, testifying to some of humanity’s vilest instincts. But she still affirmed human existence and believed in our innate capacity to participate in the ongoing and even miraculous unfolding of reality, generation after generation. This conviction was powerfully expressed in her Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities delivered in Washington, DC in March 1996.

Her lecture ‘The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations’ starts with a dire assessment: ‘Time, it seems, has no future.’ Time, an entirely human concept, ‘no longer seems to be an endless stream through which the human species moves with confidence in its own increasing consequence and value.’ Instead, humans had become increasingly adept voyagers of deep time; we could think back thousands of years, far beyond the Coliseum and Pharaohs, acutely aware of the gifts and burdens our histories have bestowed upon us. It had simultaneously and paradoxically become impossible, she observed, to think forward more than a couple of generations. Our imaginations stumble beyond the year 2030 ‘when we may be regarded as monsters to the generations that follow us.’

How had this happened?

Eden is not humanity’s future, after all, but its deep, organic, mythic past

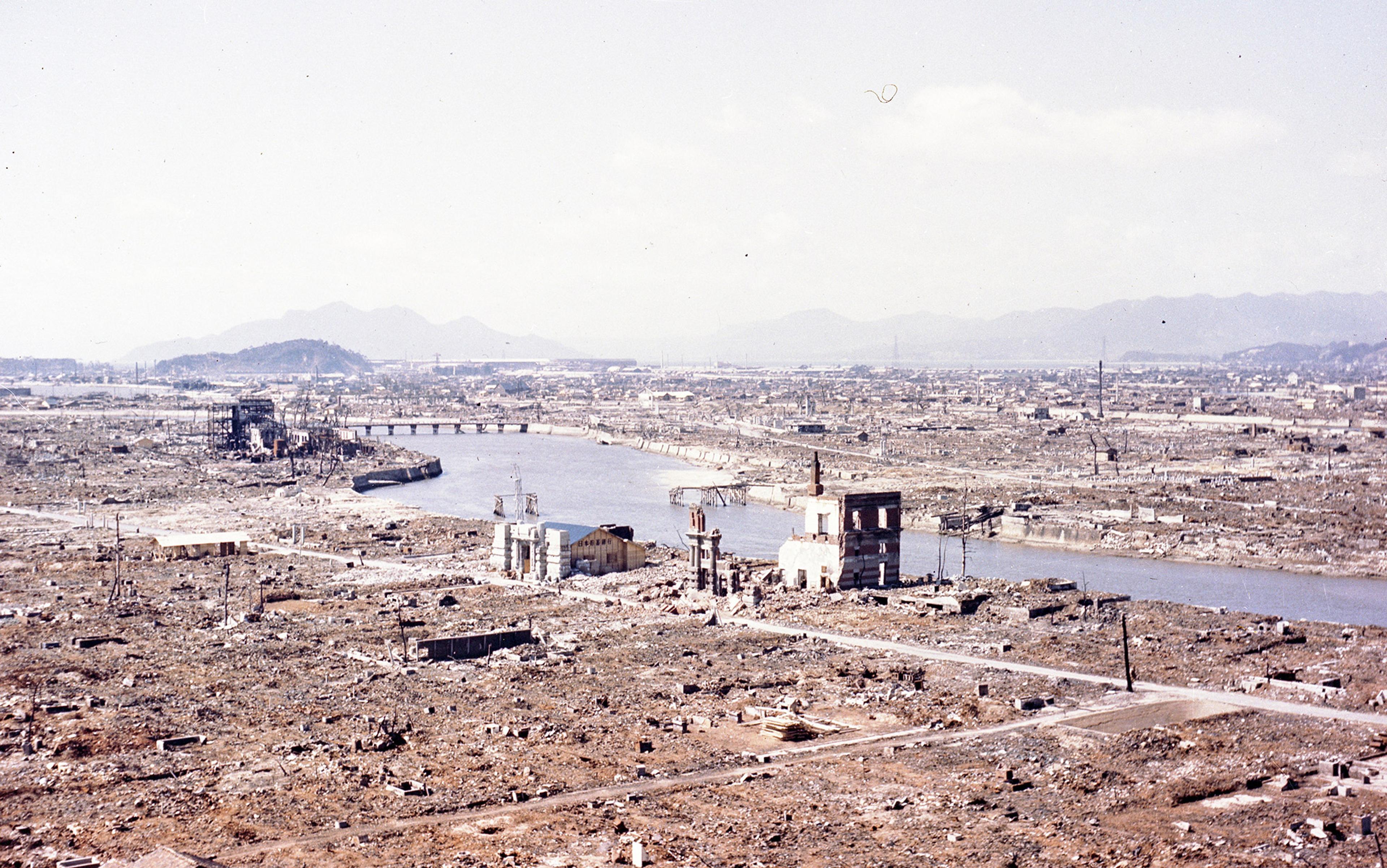

The possibility of a nuclear apocalypse, she reminds her readers, had existed for long enough and with such intensity that there ‘seemed no point in imagining the future of a species there was little reason to believe would survive.’ Secularism, she believed, was also to blame for these shrunken horizons. It was in the modern, secularised West where progress and change had been ‘signatory features’ that the outlook was dimmest. Religious ideas about life after death had become associated with naive superstition and intolerance in such societies. The modern human imagination had been trained instead ‘on the biological span of a single human being’. Rather than this awakening us to the richness of our embodied lives, it had initiated those strange attempts at escape into the recesses and ‘outer space’ of deep time.

Against these foreclosures of the future, Morrison issued a daring wager: history was ‘about to take its first unfettered breath’. She challenged her listeners to allow the years 4000 or 5000 or even 20000 to hover in their consciousness. And she catalogued a variety of novelists – Umberto Eco, Leslie Marmon Silko, Toni Cade Bambara and Salman Rushdie, among others – whose work was ‘race inflected, gendered, colonialised, displaced, hunted’ and who had courageously imagined a future for humanity. Their bright hopes paradoxically grew out of centuries of ancestral dehumanisation – a dehumanisation that had well attuned them to the reality of human limitations. The relationship between human possibility and human limits was, for her, the crux of literature. Through literature, these novelists had communicated their ‘unblinking witness to the light and shade of the world we live in’.

Although her lecture begins with time ‘narrowing to a vanishing point beyond which humanity neither exists nor wants to’, the lecture ends with Eden, the garden in which humans began the hazardous project of human embodiment in the Hebrew Bible. It’s a curious evocation for her to have ended on. Eden is not humanity’s future, after all, but its deep, organic, mythic past. Eden is furthermore not where Eve gave birth to her sons, creating a first human link in the generational lineages that follow. Childbirth happens in exile, after humanity’s epic fall, and it’s entangled with the curse set on Eve for her wilful disobedience. At the same time, God encourages his exilic creatures to ‘be fruitful and multiply’, to stretch their ancestral lines hopefully into the future. Birth is both a blessing and a curse in Genesis; it is a perennial opportunity to plant and bear new fruit, but it can happen only outside paradise, constrained by the consequences of human error.

Still, Morrison concludes, quoting the novelist William Gass, ‘There are “acres of Edens inside ourselves.” Time does have a future. Longer than its past and infinitely more hospitable – to the human race.’

In setting Morrison’s critique and prophecy in relief, against the background of simultaneous counter-movements in the culture, we can begin to see the acuity and power of her arguments. Morrison ended with the image of a generative garden, but over the next three decades Earth’s actual gardens would be ravaged at a pace unprecedented in human history. Over this same period, even as the threat of imminent nuclear war receded from the forefront of public consciousness, new technologies were rapidly developing that would, emerging transhumanists argued, pose exponentially larger threats to humanity than those posed by nuclear weapons or environmental degradation. All these threats were anthropogenic, the result of human actions. Sentient life had reached a threshold; it would either evolve into more intelligent, self-optimised, wise and moral forms, or it would probably destroy itself within centuries, if not sooner. For all their doomsday predictions, many of these same transhumanists believed that these emerging technologies, if guided by careful, coordinated oversight, could create a future in which human suffering and poverty could be eradicated. Humankind was merely in its infancy; trillions of people might still be born.

Around the time Morrison delivered her lecture, a Swedish graduate student based in London got interested in an ‘Extropy’ online discussion group focused on closely related themes. The group had come together in the late 1980s around a shared interest in transhumanism, eventually founding what they called the Extropy Institute. Like Morrison, the Extropians critiqued the contemporary focus on the biological limits of a single human life, and the thinking that foreclosed the possibility of eternal life. Unlike her, they challenged ‘entrenched dogmas concerning the inevitability of death’ and projected ‘an unlimited lifespan’ made possible by the removal or transcendence of ‘traditional, genetic, biological, and neurological limits to the pursuit of life, liberty, and boundless achievement.’

Where Morrison pessimistically saw a future contracting, they optimistically saw one expanding. Where she hopefully wagered on a human future, a future that not only contained humans but that was hospitable to them, the Extropians were betting on a different story of survival and ongoing generation, one that might evolve past the biological human entirely. Boundless expansion and self-transformation would happen not in the cities we live in, they believed, nor in the human bodies we’d been born into, but ‘here, in cyberspace, or off-Earth’.

To have any human future at all, argued Bostrom, we’ll need to wrest control of evolution

That Swedish student who joined Extropy was Nick Bostrom, now a bestselling philosopher, director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, and a thinker who has influenced such intellectual luminaries as Peter Singer and Stephen Hawking, and such business leaders as Elon Musk and Bill Gates. He made headlines in early 2023 for racist comments he’d posted via the Extropian listserv in 1997, a time and place in which he says contributors were having ‘freewheeling conversations about wild ideas’. In a series of academic papers and public presentations over the following decades, Bostrom articulated a less freewheeling transhumanism than that expressed by the early Extropians – a transhumanism characterised as much by fear as by feverish anticipation. Yet, for all its carefully worded and amply sourced delivery, this body of work has consistently exhibited an aversion to many forms of biological human life that can lead in quite dangerous directions.

Bostrom has been called a eugenicist, a broad label he repudiates while admitting that ‘I would be in favour of some uses and against others.’ His work, however, has long and unabashedly emphasised the upsides of careful and selective human breeding, a selectivity he believes could be favourable to our species collectively and in the long term. In the paper ‘The Future of Human Evolution’ (2004), he argued that, in order to have any human future at all, we’ll need to wrest control of evolution. Technological advancements, he warned, could set in motion ‘freewheeling evolutionary developments’ that might make possible the unlimited enhancements of human life, but they could also ‘lead to the gradual elimination of all forms of being that we care about’.

The potential dystopian catastrophe on the horizon is not so much that we will merge with machines or even be replaced by machines, but that these will be the wrong kinds of machines, machines without any of the consciousness, altruism, meaning or purpose we associate with being human. They would endanger what he calls ‘eudaemonic living’ and such ‘useless’ behaviours, ‘flamboyant displays’ and ‘hobbyist interests’ as joking, writing poetry, hosting parties, taking vacations, wearing fashionable clothes, and playing sports. None of these activities offer much competitive, evolutionary advantage; they are fitness inefficiencies. While eudaemonic agents are busy writing poetry and taking their vacations, the more single-mindedly competitive non-eudaemonic agents, either human or transhuman, will likely be expropriating the matter, space and sunlight they need to survive.

Evolution’s default trajectory probably runs toward this dystopian future, Bostrom gambles, but we should resist that trajectory; the eudaemonic agents, even if they don’t stand any evolutionary chance, are valuable. We want those human agents or values in our future. Existence would be less without them. This is the humanism that runs through the transhumanism Bostrom develops, but it is consequentially different than the humanism Morrison articulated, and the distinctions deserve close scrutiny.

To begin with, Morrison and Bostrom have very different understandings of what death is and how it might be experienced. Morrison, again, had criticised secularism for shrinking down human life to an exclusively biological scale. At the same time, she confronted and even accepted death as a biological limit. Life goes on after death, she believed, but the dead affirm human life more than they transcend it or reject it, as the ghosts who haunt the living in her novels make clear.

These weren’t just abstract propositions for her. In 2015, she told a reporter about a near-death experience she’d had decades earlier. ‘I left my body and I was only eyes and mind,’ she reported. ‘I could think and I could see. I didn’t try to speak because I was so fascinated with this experience.’ That death felt like a liberating weightlessness, and as much as she didn’t want to revert to weight, she tried to return to her body because she ‘had kids’ whom she needed to get back to. Death and the afterlife were where her responsibilities to the living easily trumped the liberatory weightlessness of a bodiless intelligence.

In contrast, the transhumanist project is one in which biological death ultimately no longer exists as a limit. Survival and longevity, both individual and collective, are the goals, as is evidenced in many transhumanists’ belief in a future of uploaded minds but also by their interest in cryonics. Through cryonics, our individual bodies and their intelligences can be preserved. But the preservation of human life is also a shared, collective project. If we do survive as a species, Bostrom predicts that it will be as a proactively protected minority among a vast proliferation of intelligent agents. Our continuing existence will be subsidised by a tax on the non-eudaemonic agents; we’ll be afforded an ‘affirmative action’ that is put in place by a deliberate ‘social sculpting’ of conditions.

Morrison’s and Bostrom’s parallel accounts of birth also reveal clashing understandings of what a human life is. Biological birth is constitutive of the human experience for Morrison. It is central to her work. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), begins in the doomed pregnancy of an 11-year-old girl who has been raped by her father, and her last novel, God Help the Child (2015), ends in the hopeful pregnancy of a young woman with a painful family past. In the middle of her oeuvre sits Beloved (1987), a book with one of the most incandescent birth scenes in literature, a scene followed by a terrible sequence of events. Birth in her work is creaturely, embodied, gendered, graphic, bloody, sexual and pleasurable. Her characters grasp the miracle and beauty of their own births, but they also struggle with birth’s fraught contexts and bodily costs.

A technocratic class could be strongly if selectively pro-natal

It’s on the topic of childbirth that the distinctions between Morrison’s understanding and Bostrom’s are most stark. Like Morrison, Bostrom grasps that a human future depends not only on the survival of existing people but also on the birth of new sentient beings. Our human future, he has argued, is limited both by people’s disinterest in having children, but also by the slowness of biological reproduction, which involves close to a year of gestation in another person’s body followed by roughly 15 years until sexual maturation. If people truly wanted to maximise their reproductive capacities, he argues, they’d be donating as much of their sperm and eggs to banks as humanly possible. Or they’d stop using any forms of birth control.

If cultural evolution, however, could progress more quickly than biological evolution, Bostrom posits that a ‘dominant meme set favouring plentiful offspring and opposing all forms of birth control’ might emerge. Technology is often associated with programmes intent on reducing the number of births – through, say, birth control, sterilisations or abortions – but here we can see how a technocratic class could be strongly if selectively pro-natal. Technology, Bostrom argued, could reduce birth’s biological costs and limits, and open the possibility of our boundless proliferation. Reproduction could become asexual and instantaneous. Most mating rituals – such ‘flamboyant displays’ as sports, poetry, joking and dancing – would no longer serve any evolutionary function and would likely be replaced by something like auditing firms that assess our reproductive fitness. In such a future, birth would not necessarily involve the emergence of newborn, undeveloped people. We could acquire the capacity to reproduce ourselves immaculately, making adult duplicates that would be constrained by no maturational latency. This, it seems, would be a pro-natalist world without sex, pregnancy or children – a reality in which we’d be like both God and Adam in Genesis, creator and created unified at last, free of any pregnant, cursed and paradise-wrecking Eve.

Bostrom’s solution to safeguarding the human ‘thing’ amid these reproductive revolutions involves wresting control of evolution and preventing the emergence of mutations that would heavily favour non-eudaemonic life. For digital uploads, this could be done through a series of ‘verifications’. For biological uploads, it could be done by scanning for mutations with advance gene technologies and by reproductive cloning. If this amounts to a sweeping eugenics project focused on saving humanity from itself, Bostrom seems reconciled to its moral downsides.

To oversee such an ambitious and complex project, he argues, humanity would need a ‘singleton’, a ‘global regime that could enforce basic laws for its members’. This singleton would be coordinative and stable, and its rule uncontested. It could take different forms – democratic or dictatorial, moral or machine – but it would absolutely depend on transparency, on being able to see into the lives of all sentient beings, to observe their actions but also such intimate details as their genetic codes.

In the paper ‘The Vulnerable World Hypothesis’ (2019), he provides further clues as to what such a ‘High-tech Panopticon’ might look like. Everyone would be fitted with a ‘freedom tag’, he explains, an appliance ‘worn around the neck and bedecked with multidirectional cameras and microphones’. This would be a crucial piece of ‘preventive policing’ in a system of ‘turnkey totalitarianism’, which would of course come with its own considerable risks. But those risks just might be worth it, he challenges his readers to see, if they can save us from the threat of massive civilisational destruction wrought by one of our fellow humans gone rogue.

If this is our future, do we really want to live to see it? In Morrison’s words: ‘No wonder the next 20 or 40 years is all anyone wants to contemplate.’

The word ‘colonise’ comes up a lot in the transhumanists’ writings; they dream of colonising outer space – a place that appears empty and ripe for possession. But the global surveillance regime Bostrom imagines also entails an invasion of every corner of our inner lives as well. Here we can see how far we have travelled from Said’s postcolonial humanism, or Morrison’s humanism of the displaced, both of which always prioritised the rights of individual human actors, balancing them with responsibility, care, weight and limits, but never losing sight of freedom’s constitutive role in any sane society.

Transhumanism may well be the wave of the future; we are surely several steps along its path already. In such a future, Bostrom’s ‘eudaemonic agents’ might read Morrison’s lecture as yet another disappointed prophecy, but one that remains strangely resonant. Her humanism of the displaced would accrue eerie relevance after the entire human species is colonised and left to linger on as a curious species of useless hobbyists, subsisting on the altruistic but reluctant patrimony of superintelligent, non-biological beings.

But the future remains before us, as unthinkable as the farthest reaches of our still-uncolonised galaxy, or the startling mystery of our own births and deaths. I like to believe there’s still time to salvage whatever sane humanisms we can from the wreckage of modern history, to practise Said’s ‘exigent, resistant, intransigent’ arts, and to vindicate Morrison’s prophecy. The future, I hope, will remain hospitable to our species and to our children. The year 2030, the one that Morrison said our imaginations stumbled beyond, beyond which ‘we may be regarded as monsters to the generations that follow us’, is now just six short years away.