The end of the world is a growth industry. You can almost feel Armageddon in the air: from survivalist and ‘prepper’ websites (survivopedia.com, doomandbloom.net, prepforshtf.com) to new academic disciplines (‘disaster studies’, ‘Anthropocene studies’, ‘extinction studies’), human vulnerability is in vogue.

The panic isn’t merely about civilisational threats, but existential ones. Beyond doomsday proclamations about mass extinction, climate change, viral pandemics, global systemic collapse and resource depletion, we seem to be seized by an anxiety about losing the qualities that make us human. Social media, we’re told, threatens our capacity for empathy and genuine connection. Then there’s the disaster porn and apocalyptic cinema, in which zombies, vampires, genetic mutants, artificial intelligence and alien invaders are oh-so-nearly human that they cast doubt on the value and essence of the category itself.

How did we arrive at this moment in history, in which humanity is more technologically powerful than ever before, and yet we feel ourselves to be increasingly fragile? The answer lies in the long history of how we’ve understood the quintessence of ‘the human’, and the way this category has fortified itself by feeding on the fantasy of its own collapse. Fears about the frailty of human wisdom go back at least as far as Ancient Greece and the fable of Plato’s cave, in which humans are held captive and can only glimpse the shadows of true forms flickering on the stone walls. We prisoners struggle to turn towards the light and see the source (or truth) of images, and we resist doing so. In another Platonic dialogue, the Phaedrus, Socrates worries that the very medium of knowledge – writing – might discourage us from memorising and thinking for ourselves. It’s as though the faculty of reason that defines us is also something we’re constantly in danger of losing, and even tend to avoid.

This paradoxical logic of loss – in which we value that which we’re at the greatest risk of forsaking – is at work in how we’re dealing with our current predicament. It’s only by confronting how close we are to destruction that we might finally do something; it’s only by embracing the vulnerability of humanity itself that we have any hope of establishing a just future. Or so say the sages of pop culture, political theory and contemporary philosophy. Ecological destruction is what will finally force us to act on the violence of capitalism, according to Naomi Klein in This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate (2014). The philosopher Martha Nussbaum has long argued that an attempt to secure humans from fragility and vulnerability explains the origins of political hierarchies from Plato to the present; it is only if we appreciate our own precarious bodily life, and the emotions and fears that attach to being human animals, that we can understand and overcome racism, sexism and other irrational hatreds. Disorder and potential destruction are actually opportunities to become more robust, argues Nassim Nicholas Taleb in Antifragile (2012) – and in Thank You for Being Late (2016), the New York Times’ columnist Thomas Friedman claims that the current, overwhelming ‘age of accelerations’ is an opportunity to take a pause. Meanwhile, Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute pursues research focused on avoiding existential catastrophes, at the same time as working on technological maturity and ‘superintelligence’.

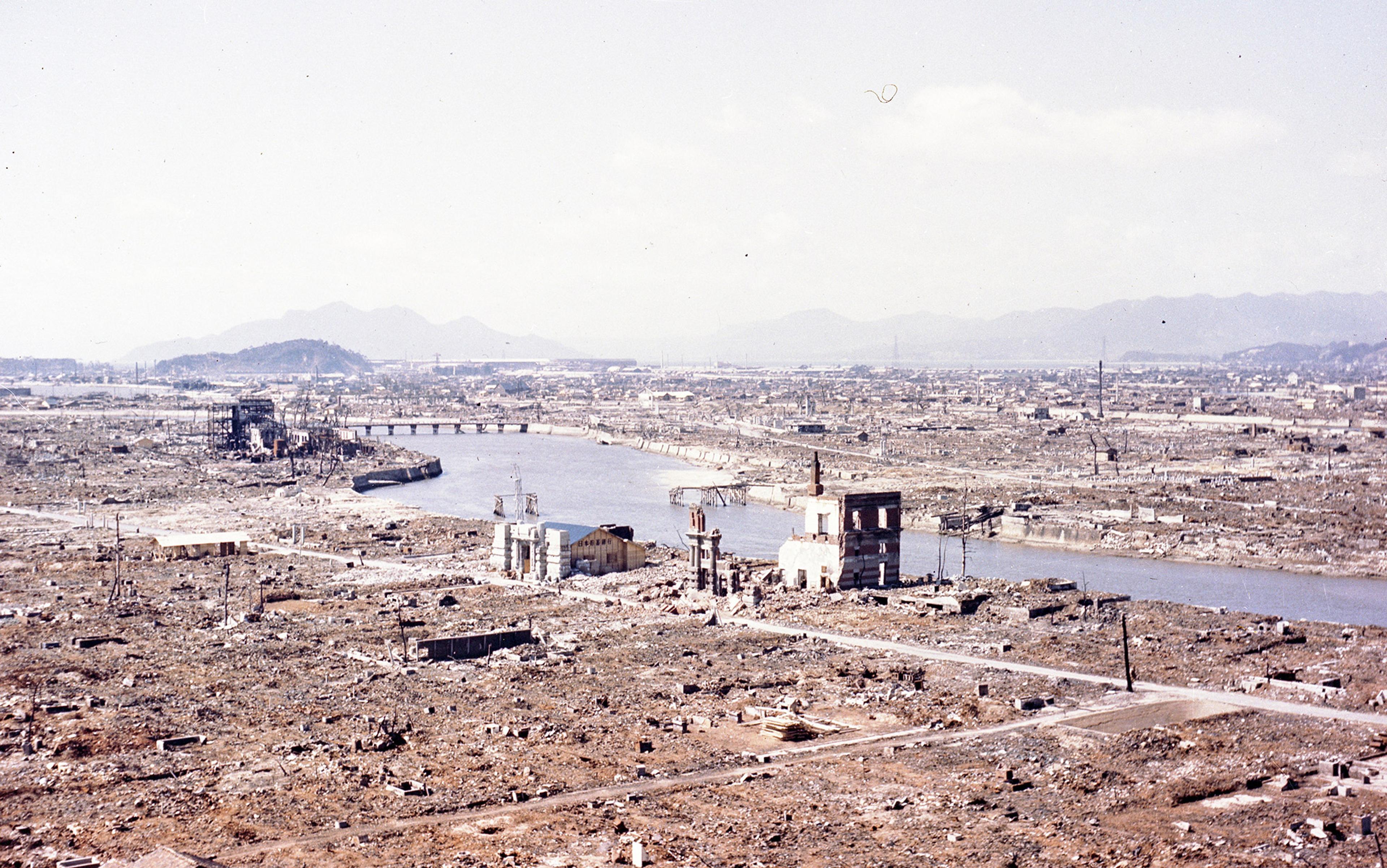

It’s here that one can discern a tight knit between fragility and virility. ‘Humanity’ is a hardened concept, but a brittle one. History suggests that the more we define ‘the human’ as a subject of intellect, mastery and progress – the more ‘we’ insist on global unity under the umbrella of a supposedly universal kinship – the less possible it becomes to imagine any other mode of existence as human. The apocalypse is typically depicted as humanity reduced to mere life, fragile, exposed to all forms of exploitation and the arbitrary exercise of power. But these dystopian future scenarios are nothing worse than the conditions in which most humans live as their day-to-day reality. By ‘end of the world’, we usually mean the end of our world. What we don’t tend to ask is who gets included in the ‘we’, what it cost to attain our world, and whether we were entitled to such a world in the first place.

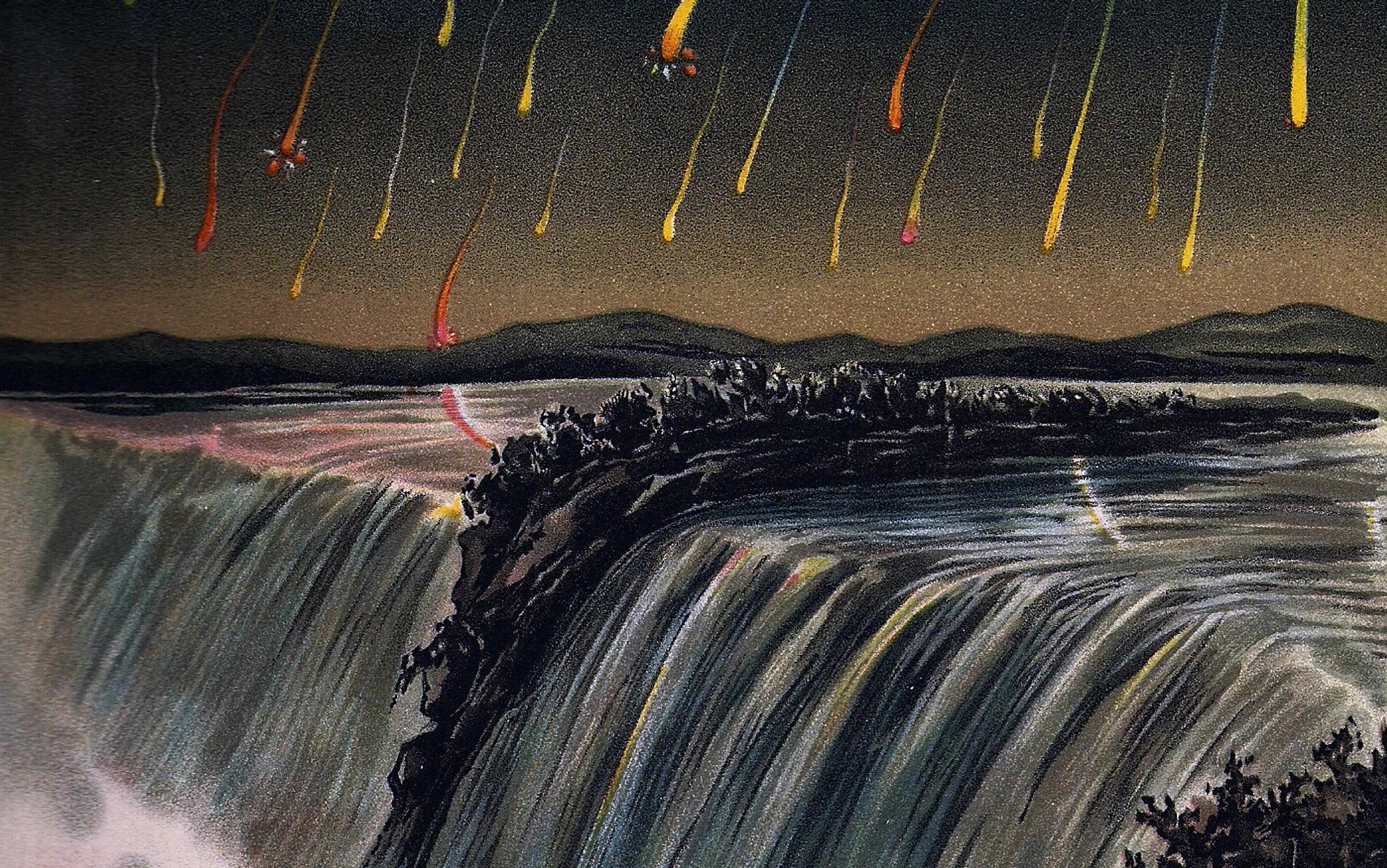

Stories about the end of time have a long history, from biblical eschatology to medieval plague narratives. But our fear of a peculiarly ‘human’ apocalypse really begins with the 18th-century Enlightenment. This was the intellectual birthplace of the modern notion of ‘humanity’, a community of fellow beings united by shared endowments of reason and rights. This humanist ideal continues to inform progressive activism and democratic discourse to this day. However, it’s worth taking a moment to go back to René Descartes’s earlier declaration of ‘I think, therefore I am’, and ask how it was possible for an isolated self to detach their person from the world, and devote writing, reading and persuasion to the task of defending an isolated and pure ego. Or fast-forward a few centuries to 1792, and consider how Mary Wollstonecraft had the time to read about the rights of man, and then demand the rights of woman.

The novelist Amitav Ghosh provides a compelling answer in his study of global warming, The Great Derangement (2017). Colonisation, empire and climate change are inextricably intertwined as practices, he says. The resources of what would become the Third World were crucial in creating the comfortable middle-class existences of the modern era, but those resources could not be made available to all: ‘the patterns of life that modernity engenders can only be practised by a small minority … Every family in the world cannot have two cars, a washing machine and a refrigerator – not because of technical or economic limitations but because humanity would asphyxiate in the process.’

Ghosh disputes one crucial aspect of the story of humanity: that it should involve increasing progress and inclusion until we all reap the benefits. But I’d add a further strand to this dissenting narrative: the Enlightenment conception of rights, freedom and the pursuit of happiness simply wouldn’t have been imaginable if the West had not enjoyed a leisured ease and technological sophistication that allowed for an increasingly liberal middle class. The affirmation of basic human freedoms could become widespread moral concerns only because modern humans were increasingly comfortable at a material level – in large part thanks to the economic benefits afforded by the conquest, colonisation and enslavement of others. So it wasn’t possible to be against slavery and servitude (in the literal and immediate sense) until large portions of the globe had been subjected to the industries of energy-extraction. The rights due to ‘us all’, then, relied on ignoring the fact that these favourable conditions had been purchased at the expense of the lives of other humans and non-humans. A truly universal entitlement to security, dignity and rights came about only because the beneficiaries of ‘humanity’ had secured their own comfort and status by rendering those they deemed less than human even more fragile.

What’s interesting about the emergence of this 18th-century humanism isn’t only that it required a prior history of the abjection it later rejected. It’s also that the idea of ‘humanity’ continued to have an ongoing relation to that same abjection. After living off the wealth extracted from the bodies and territories of ‘others’, Western thought began to extend the category of ‘humanity’ to capture more and more of these once-excluded individuals, via abolitionism, women’s suffrage and movements to expand the franchise. In a strange way these shifts resemble the pronouncements of today’s tech billionaires, who, having extracted unimaginable amounts of value from the mechanics of global capitalism, are now calling for Universal Basic Income to offset the impacts of automation and artificial intelligence. Mastery can afford to correct itself only from a position of leisured ease, after all.

But there’s a twist. While everyone’s ‘humanity’ had become inherent and unalienable, certain people still got to be more fully ‘realised’ as humans than others. As the circle of humanity grew to capture the vulnerable, the risk that ‘we’ would slip back into a semi-human or non-human state seemed more present than before – and so justified demands for an ever more elevated and robust conception of ‘the human’.

‘Humanity’ was to be cherished and protected precisely because it was so precariously elevated above mere life

One can see this dynamic at work in the 18th-century discussions about slavery. By then the practice itself had become morally repugnant, not only because it dehumanised slaves, but because the very possibility of enslavement – of some humans not realising their potential as rational subjects – was considered pernicious for humanity as a whole. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), for example, Wollstonecraft compared women to slaves, but insisted that slavery would allow no one to be a true master. ‘We’ are all rendered more brutal and base by enslaving others, she said. ‘[Women] may be convenient slaves,’ Wollstonecraft wrote, ‘but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent.’

These statements assumed that an entitlement to freedom was the natural condition of the ‘human’, and that real slavery and servitude were no longer genuine threats to ‘us’. When Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued in The Social Contract (1762) that ‘man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains’, he was certainly not most concerned about those who were literally in chains; likewise William Blake’s notion of ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ implies that the true horror is not physical entrapment but a capacity to enslave oneself by failing to think. It’s thus at the very moment of abolition, when slavery is reduced to a mere symbol of fragility, that it becomes a condition that imperils the potency of humanity from within.

I’m certainly not suggesting that there is something natural or inevitable about slavery. What I’m arguing is that the very writers who argued against slavery, who argued that slavery was not fitting for humans in their very nature, nevertheless saw the unnatural and monstrous potential for slavery as far too proximate to humans in their proper state. Yet rather than adopt a benevolence towards the world in light of this vulnerability in oneself, the opposite has tended to be the case. It is because humans can fail to reach their rational potential and be ‘everywhere in chains’ that they must ever more vigilantly secure their future. ‘Humanity’ was to be cherished and protected precisely because it was so precariously elevated above mere life. The risk of debasement to ‘the human’ turned into a force that solidified and extended the category itself. And so slavery was not conceived as a historical condition for some humans, subjected by ruthless, inhuman and overpowering others; it was an ongoing insider threat, a spectre of fragility that has justified the drive for power.

How different are the stories we tell ourselves today? Movies are an interesting barometer of the cultural mood. In the 1970s, cinematic disaster tales routinely featured parochial horrors such as shipwrecks (The Poseidon Adventure, 1972), burning skyscrapers (The Towering Inferno, 1974), and man-eating sharks (Jaws, 1975). Now, they concern the whole of humanity. What threatens us today are not localised incidents, but humans. The wasteland of Interstellar (2014) is one of resource depletion following human over-consumption; the world reduced to enslaved existence in Elysium (2013) is a result of species-bifurcation, as some humans seize the only resources left, while those left on Earth enjoy a life of indentured labour. That the world will end (soon) seems to be so much a part of the cultural imagination that we entertain ourselves by imagining how, not whether, it will play out.

But if you look closely, you’ll see that most ‘end of the world’ narratives end up becoming ‘save the world’ narratives. Popular culture might heighten the scale and intensity of catastrophe, but it does so with the payoff of a more robust and final triumph. Interstellar pits the frontier spirit of space exploration over a miserly and merely survivalist bureaucracy, culminating with a retired astronaut risking it all to save the world. Even the desolate cinematic version (2009) of Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road (2006) concludes with a young boy joining a family. The most reduced, enslaved, depleted and lifeless terrains are still opportunities for ‘humanity’ to confront the possibility of non-existence in order to achieve a more resilient future.

Such films hint at a desire for new ways of being. In Avatar (2009), a militaristic and plundering West invades the moon Pandora in order to mine ‘unobtanium’; they are ultimately thwarted by the indigenous Na’vi, whose attitude to nature is not one of acquisition but of symbiotic harmony. Native ecological wisdom and attunement is what ultimately leads to victory over the instrumental reason of the self-interested invaders. In Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), a resource-depleted future world is controlled by a rapacious, parasitic, and wasteful elite. But salvation comes from the revolutionary return of a group of ecologically attuned and other-directed women, all blessed with a mythic wisdom that enables ultimate triumph over the violent self-interest of the literally blood-sucking tyrant family. These stories rely on quasi-indigenous and feminist images of community to offer alternatives to Western hyper-extraction; both resolve their disaster narratives with the triumph of intuitive and holistic modes of existence over imperialism and militarism. They not only depict the post-post-apocalyptic future in joyous terms, but do so by appealing to a more benevolent and ecologically attuned humanity.

These films whisper: take a second glance at the present, and what looks like a desperate situation might actually be an occasion for enhancement. The very world that appears to be at the brink of destruction is really a world of opportunity. Once again, the self-declared universal humanity of the Enlightenment – that same humanity that enslaved and colonised on the grounds that ‘we’ would all benefit from the march of reason and progress – has started to appear as both fragile and capable of ethical redemption. It’s our own weakness, we seem to say, that endows humanity with a right to ultimate mastery.

If everything that is ‘the human’ relies upon an exploitative existence, then any diminution is deemed apocalyptic

What contemporary post-apocalyptic culture fears isn’t the end of ‘the world’ so much as the end of ‘a world’ – the rich, white, leisured, affluent one. Western lifestyles are reliant on what the French philosopher Bruno Latour has referred to as a ‘slowly built set of irreversibilities’, requiring the rest of the world to live in conditions that ‘humanity’ regards as unliveable. And nothing could be more precarious than a species that contracts itself to a small portion of the Earth, draws its resources from elsewhere, transfers its waste and violence, and then declares that its mode of existence is humanity as such.

To define humanity as such by this specific form of humanity is to see the end of that humanity as the end of the world. If everything that defines ‘us’ relies upon such a complex, exploitative and appropriative mode of existence, then of course any diminution of this hyper-humanity is deemed to be an apocalyptic event. ‘We’ have lost our world of security, we seem to be telling ourselves, and will soon be living like all those peoples on whom we have relied to bear the true cost of what it means for ‘us’ to be ‘human’.

The lesson that I take from this analysis is that the ethical direction of fragility must be reversed. The more invulnerable and resilient humanity insists on trying to become, the more vulnerable it must necessarily be. But rather than looking at the apocalypse as an inhuman horror show that might befall ‘us’, we should recognise that what presents itself as ‘humanity’ has always outsourced its fragility to others. ‘We’ have experienced an epoch of universal ‘human’ benevolence, a globe of justice and security as an aspiration for all, only by intensifying and generating utterly fragile modes of life for other humans. So the supposedly galvanising catastrophes that should prompt ‘us’ to secure our stability are not only things that many humans have already lived through, but perhaps shouldn’t be excluded from how we imagine our own future.

This is why contemporary disaster scenarios still depict a world and humans, but this world is not ‘the world’, and the humans who are left are not ‘humanity’. The ‘we’ of humanity, the ‘we’ that imagines itself to be blessed with favourable conditions that ought to extend to all, is actually the most fragile of historical events. If today ‘humanity’ has started to express a sense of unprecedented fragility, this is not because a life of precarious, exposed and vulnerable existence has suddenly and accidentally interrupted a history of stability. Rather, it reveals that the thing calling itself ‘humanity’ is better seen as a hiatus and an intensification of an essential and transcendental fragility.