In The Matrix (1999), one of the machines’ sharp-suited kung-fu enforcers, Agent Jones, is standing over Neo on a rooftop, about to kill him. Jones looks down and sneers: ‘Only human.’ Arguably it is something like this contempt for the merely human — or a kind of embarrassment at it — that has driven actual humans over the millennia to seek to enhance themselves. For a long time now, indeed, few of us have been ‘only human’ in the sense of getting by solely on what biology has given us. Spectacles, contact lenses, dental crowns and implants, pacemakers, running shoes — all are technological improvements to the capacities of a human body. Even clothes (adopted, according to the Book of Genesis, after a moment of shame at what is ‘only human’) are enhancements, enabling us to live in hostile climates. Today, improvements in cognitive pharmaceuticals, genetic engineering and high-tech prostheses inspire some to dream of a future of accelerating species enhancement, reaching a point where we will have become — what? Übermenschen? Cyborgs? Post-humans? Or just better versions of ourselves?

In Emily Sargent’s artfully curated exhibition, Superhuman, at the Wellcome Trust in London this summer, sci-fi visions of future improvements were presented side-by-side with artifacts from the history of human enhancement. Here was a wooden big toe: an ancient Egyptian prosthesis, from around 600 BCE. At first it was thought that such appendages were only for dead pharaohs, so that the passage to the afterlife could be made by a body that was complete; more recently, researchers have found that such prosthetics might have been used by the living as well. The exhibition also displayed an 18th-century ‘ivory dildo complete with contrivance for simulating ejaculation’. The 19th century even saw a brisk trade in false noses attached to spectacle frames, thanks to the prevalence of syphilis.

One section of the exhibition was devoted to athletic enhancement; and many of the central arguments over human enhancement are played out today in the crucible of professional sport. The cyclist Lance Armstrong’s alleged use of cortisone, testosterone, the hormone EPO and blood transfusions has led him to be stripped of his Tour de France titles. Disappointed commentators have claimed that he simply didn’t want to work hard, even that he was ‘lazy’. But no one seriously thinks that Armstrong just sprawled around on his couch popping magic sports pills and drinking daiquiris. Indeed, if — as is alleged — the majority of professional cyclists were using such biochemical helpers at the time, then Armstrong’s victories proved he was better than anyone else at exploiting their effects through hard practice. In that sense, he deserved to win. The only objection to such a judgment is the existence of some riders who were not doping, and for whom it was therefore a rigged contest — even if they would not have won anyway. So while one solution is to ban drugs, another would be to compel — or at least allow — everyone to take them.

There are many chemical enhancements available to modern athletes that no one complains about: vitamins, highly tuned dietary science, even mineral-replenishing sports drinks. To allow these but not other chemical aids is to draw an arbitrary line merely because some such line, it is felt, must be drawn. People who want to eliminate doping in sport sometimes say that this is the only way sporting contests will be ‘fair’. But no sporting contest is ever fair. Some people are just born with the genes to make them faster, bigger or stronger than others. And some people are born into countries with better training programmes and more high-tech equipment than others. But this does not always guarantee success — witness the heartening victories of Usain Bolt and his Jamaican colleagues in sprinting. Still, we should not kid ourselves that undrugged athletes are ever competing on a level playing field. We watch sport in order to enjoy the results of an interplay between hard work and a genetic lottery.

Arguably, it would be fairer if athletes were allowed to exploit the whole modern pharmacopoeia to make up for their hard-wired disadvantages. True, previous anything-goes eras did not always result in triumphs of perfect dignity. Thomas Hicks staggered delirious over the finishing line of the 1904 Olympic marathon having received doses of strychnine and egg white washed down with brandy along the way. But one has also to contend with an argument made by the French writer Marc Perelman, in his witty polemic Barbaric Sport: A Global Plague (2012). Rampant and ubiquitous doping, he says, is indispensable to the spectacle of modern industrialised athletics, which depends on the frequent breaking of records. Other writers argue that research into sports drugs should be encouraged because it would inevitably produce spin-off therapies for the wider population. And Andy Miah, professor of ethics and emerging technologies at the University of the West of Scotland, argues in the Superhuman exhibition’s catalogue that, as chemical enhancements become widely used in society in the future, it will no longer make any sense to deny athletes the use of them as well.

The cat-and-mouse history of sports doping intersects with the story of mechanical enhancement through prosthetics in the peculiar shape of the 1980s Whizzinator, a device consisting of underpants, tubes, and a false penis, engineered to help athletes give false urine samples to drug inspectors. (It is now marketed as a sex toy, which just goes to show that there exists a monetisable fetish for just about anything.) Controversy arose this summer over the legitimacy of certain mechanical aids to athletic achievement. Oscar Pistorius, the South African sprinter who runs on prosthetic ‘blades’, competed in both the Olympics and the Paralympics this year. After his defeat in the Paralympic 200m final, he suggested that the winner, Alan Oliveira from Brazil, was using blades that were too long, giving him an unwarranted advantage. It was subsequently confirmed that Oliveira’s blades were within regulations, but how those regulations are themselves determined must be a subtle matter.

In any case, a similar advantage might have been had in the late 19th century by a runner using a newfangled set of spiked shoes, or by an athlete in the 1970s who was quick to adopt Nike’s waffle-soled trainer, or by the first tennis players to use metal-framed racquets. In swimming, the full-body LZR Racer swimsuit worn by many competitors in the 2008 Beijing Olympics was subsequently banned for being too fast, although it is difficult to see why, since all racers had the opportunity to wear one. A Marc Perelman-inspired cynic might suggest that, while records must constantly be broken to preserve the profitable spectacle of industrial sporting events, you should take care that they are not smashed by too great a margin too quickly. That, after all, will slow the pace of future telegenic record-breaking.

Sporting enhancement is designed to make us measurably better, but culture has long been ambivalent about the practice of meddling with natural bodies. Hence the dark side of enhancement: the genre of prosthesis-horror, as in all those uncanny tales about a man receiving a new hand in surgery that used to belong to a killer, and which still has a murderous mind of its own. Visions of ever-more-elaborate mechanical enhancement of the human body seem to evoke two poles of emotion — on the one hand, optimism and admiration for the electrically enhanced hero (The Bionic Man); and on the other, a dystopian dread, as people who are re-engineered with mechanical parts become indistinguishable from machines cunningly skinned with human flesh (The Terminator).

‘It is human intelligence that puts humans in the driving seat, so when something else comes along that is more intelligent, they will take over’

Terminator cyborgs need to look like humans in order to accomplish their assassination missions. But why, one might pause to wonder, are so many researchers right now trying to build humanoid robots that mimic the human bipedal gait as closely as possible? Presumably they don’t plan to send them back in time to murder anti-Skynet rebels. The Superhuman exhibition displayed some such robots in progress in engineering labs around the world, including a marvelously uncanny picture of a Japanese robot scientist, Hiroshi Ishiguro, sitting next to his own robot doppelganger. An anthropoid robot can hardly be the most efficient possible general-purpose design. No doubt there are some wonderful trickle-down innovations that arise out of such research, but the fascination with human-shaped robots — or androids — is more likely part of the continuing celebration of ourselves as both makers and marvels of engineering, as with the fashion in the 18th and 19th centuries for elaborate automata. But this is a paradoxical kind of celebration that potentially carries an undercurrent of misanthropy, hinting — or even hoping — that one day we could be replaced by our own machines.

Some people take that possibility seriously. It is to reconcile us to what he considers our brightly inevitable cyborg future that Kevin Warwick, professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, styles himself ‘the world’s first cyborg’ and enthusiastically publicises his own self-enhancements. Warwick implanted a neural-electronic interface into himself that let him control robots over the internet by thinking, and allowed him to perceive ultrasonic noises, like a bat. He stuck another such chip into his wife, Irena. The result was the first exclusively electronic communication between two human nervous systems.

This all sounds like fun, but there is a more doom-inspired motivation at work. ‘We must be aware that the technological singularity — as depicted in The Terminator or The Matrix — when intelligent machines take over as the dominant life form on earth — is a realistic possibility,’ Warwick once told me in an interview. ‘It is human intelligence that puts humans in the driving seat, so when something else comes along that is more intelligent, they will take over.’ Unless we have already made sure to enhance our own powers, and become super-cyborgs able to defeat the upstart machines at their own game. As the inventor Ray Kurzweil (who popularised the idea of the singularity) put it, there is no reason to fear the arrival of malign super-intelligent machines, because: ‘It will not be a matter of us versus them. We will become the machines.’

For some, perhaps, this is a consummation devoutly to be wished. But it also reveals the essentially religious nature of much singularity-style techno-futurism: such visions constitute an eschatology in which human beings finally sublime into the cybersphere. It is the silicon Rapture — and this reminds us that ‘to enhance’ once meant literally ‘to raise up’. This desire to become machinic implicitly betrays a hatred of the flesh as severe as that of self-flagellating religious ascetics. For the devout of singularity theory, the perfection of humanity is synonymous with its destruction.

The robopocalypse, as well as climatic Armageddon and most other projected planetary disasters, could perhaps be avoided if we could only enhance the human mind itself. There are already some venerable drugs that enhance cognitive performance: coffee and nicotine, for example. If you could take a future ‘smart drug’ that made you more intelligent with no side effects, why wouldn’t you? Medications such as the ADHD treatments Adderall and Ritalin, or the narcolepsy therapy Modafinil, are increasingly used without prescription by American undergraduate students cramming for exams: the Lance Armstrongs of the university library. But their unenhanced colleagues will feel a pressure to keep up: if everyone else is doing it, the option to meddle with your own neurochemistry might feel like an onerous compulsion. In the dog-eat-dog world of a dystopian corporate future, popping ‘smart’ pills could become as basic a prerequisite of success as wearing a suit.

As Allen Buchanan, professor of philosophy at Duke University, North Carolina, writes in his excellent short book on human enhancement, Better Than Human (2011): ‘It’s too late to “just say no” to biomedical enhancements.’ They’re already here — and, he points out, it would be cruel to try to stop them, given that so many enhancements were originally developed as treatments for specific diseases that were then found to benefit everyone. (He points out that Viagra is now used recreationally, and some people without depression feel better on SSRIs. Enhancement, Buchanan argues, is ‘a legitimate social aim’; but we need urgently to start thinking about the appropriate social and legal frameworks.

‘I think many people have a horror of playing God, but if they reflected on how bad a job God was doing most of the time, they would lose that horror’

At this point a canny enthusiast might suggest that we’re more likely to make good judgments about future enhancements if we first enhance our judgment-making capacity. Indeed, some thinkers argue that there is actually a moral obligation on us to enhance ourselves by any means necessary. For example, Julian Savulescu, professor of practical ethics at the University of Oxford, argues in the Superhuman catalogue that we are ethically obliged to pursue research into ‘moral enhancement’ drugs. ‘The threat to our survival,’ he writes, comes mainly ‘from the choices that we make through religious fundamentalism or excessive consumption of our resources and our climate, through our failure to bring about global equality and global justice.’ Therefore we are obliged to make ourselves nicer. ‘Unless you believe that evolution provided just the perfect number of psychopaths in our community and just the right level of selfishness within different individuals, you should believe that we should change that natural distribution for the better and use science to do that.’

This sounds splendid, until one wonders how we are all to agree on what exactly the morally ideal kind of mind is before we impose it neurochemically on others, assuming that ever becomes possible. Savulescu accepts that there will be ‘those who are sceptical about making humans morally better’, but argues that ‘at the very least we should try to reduce the distorting influences and also the natural inequality in moral capacities that already exists’. It’s hard to gainsay the desirability of curing psychopaths, at least. Meanwhile, John Harris, professor of bioethics at the University of Manchester, argues that there is a moral obligation to pursue all kinds of biomedical enhancements — to our moral and cognitive capacities, to our lifespans, our immune systems, and so forth — so that human beings can survive without destroying their environmental life-support system, and so that we are able, in a far-distant future, to move to another planet when Earth is swallowed up by an angry red Sun. ‘I’m mystified by the resistance that human enhancement faces,’ Harris writes in the Superhuman exhibition catalogue. ‘I think many people have a horror of playing God, but if they reflected on how bad a job God was doing most of the time, they would lose that horror.’

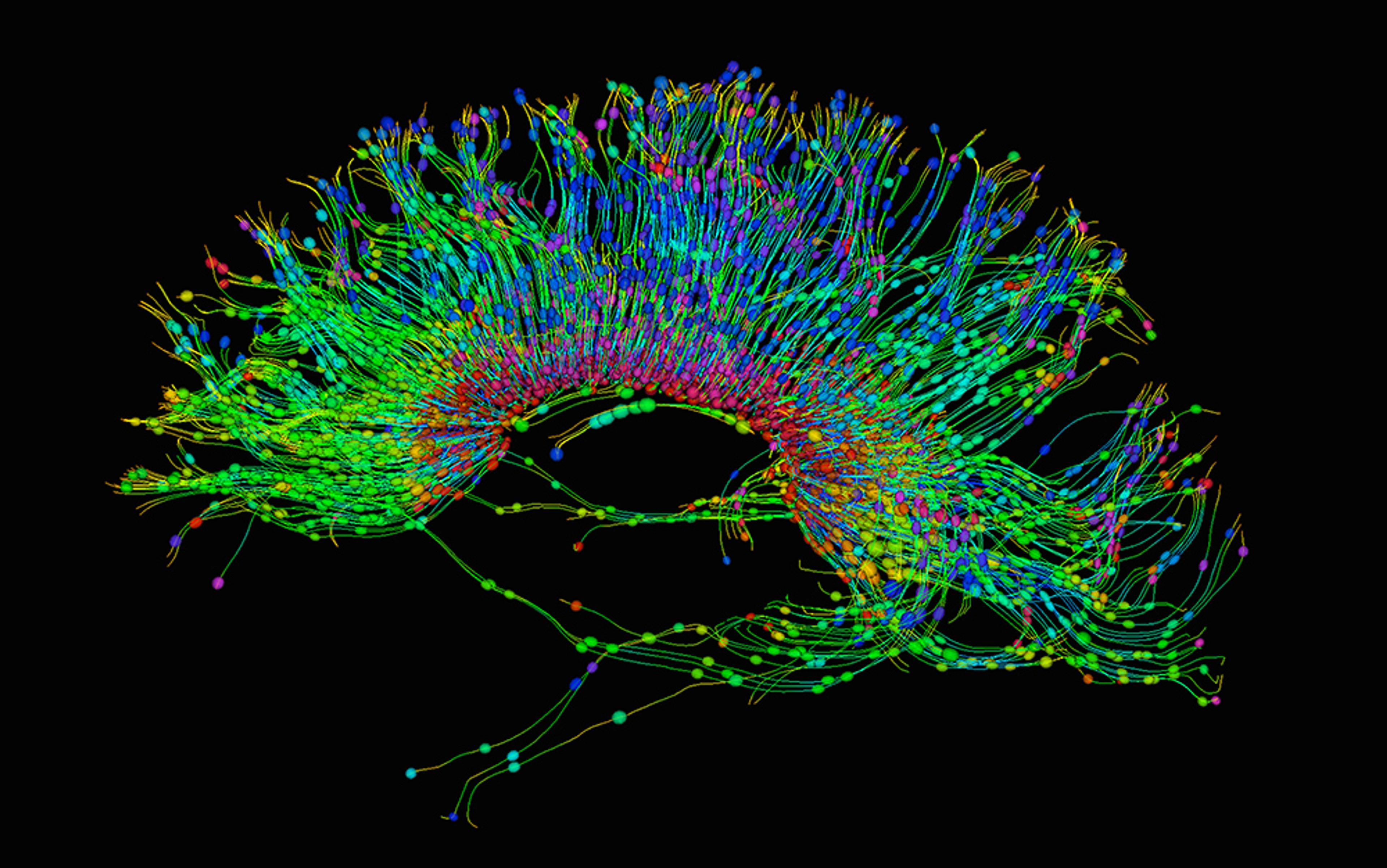

The final exhibit of the Superhuman exhibition was an inspirational board featuring the predictions of contributors to conferences organised by the US National Science Foundation, on how they imagined human abilities would develop during the rest of the 21st century. The rhetorical mode is a sunny techno-Panglossianism. Thanks to science, humans will just keep on getting fitter, happier, more productive. In 2020, for example, ‘People from all backgrounds and of all ranges of ability will acquire valuable new knowledge and skills more reliably and quickly, whether at school, work or at home’. In 2030, ‘Fast, broadband interfaces between the human brain and machines will transform work in factories, control cars, and enable new sports, art forms and modes of interaction between people.’ (I think this means we could have play fights with each other using mentally controlled giant robots, which would obviously be cool.)

But the most revealingly naive prediction was this, scheduled to come true a mere 18 years from now: ‘The ability to control the genetics of humans, animals, and agricultural plants will greatly benefit human welfare; widespread consensus about ethical, legal, and moral issues will be built in the process.’

This is truly a marvellous apogee of technocratic utopianism. Global agreement on ‘ethical, legal, and moral’ issues has been out of reach for all of recorded human civilisation, at least through the traditional means of reasoning and persuasion. Just because we might become as gods with regard to the molecular building blocks of life doesn’t mean we won’t continue to bicker and squabble. After all, that’s just what communities of gods spend most of their time doing in polytheistic mythologies. Or perhaps we are meant to read this future consensus as one propagated by morally improving chemistry. But such obligatory improvement of all citizens will be a kind of neural slavery in the service of a totalitarian liberalism. And so we come full circle: in a future of ubiquitous mandatory enhancement, the truly radical act might be, after all, to downgrade yourself.