It was a November night in Islamabad, not too different from that evening when the assassins came for me. The two nights are inseparable in my memory.

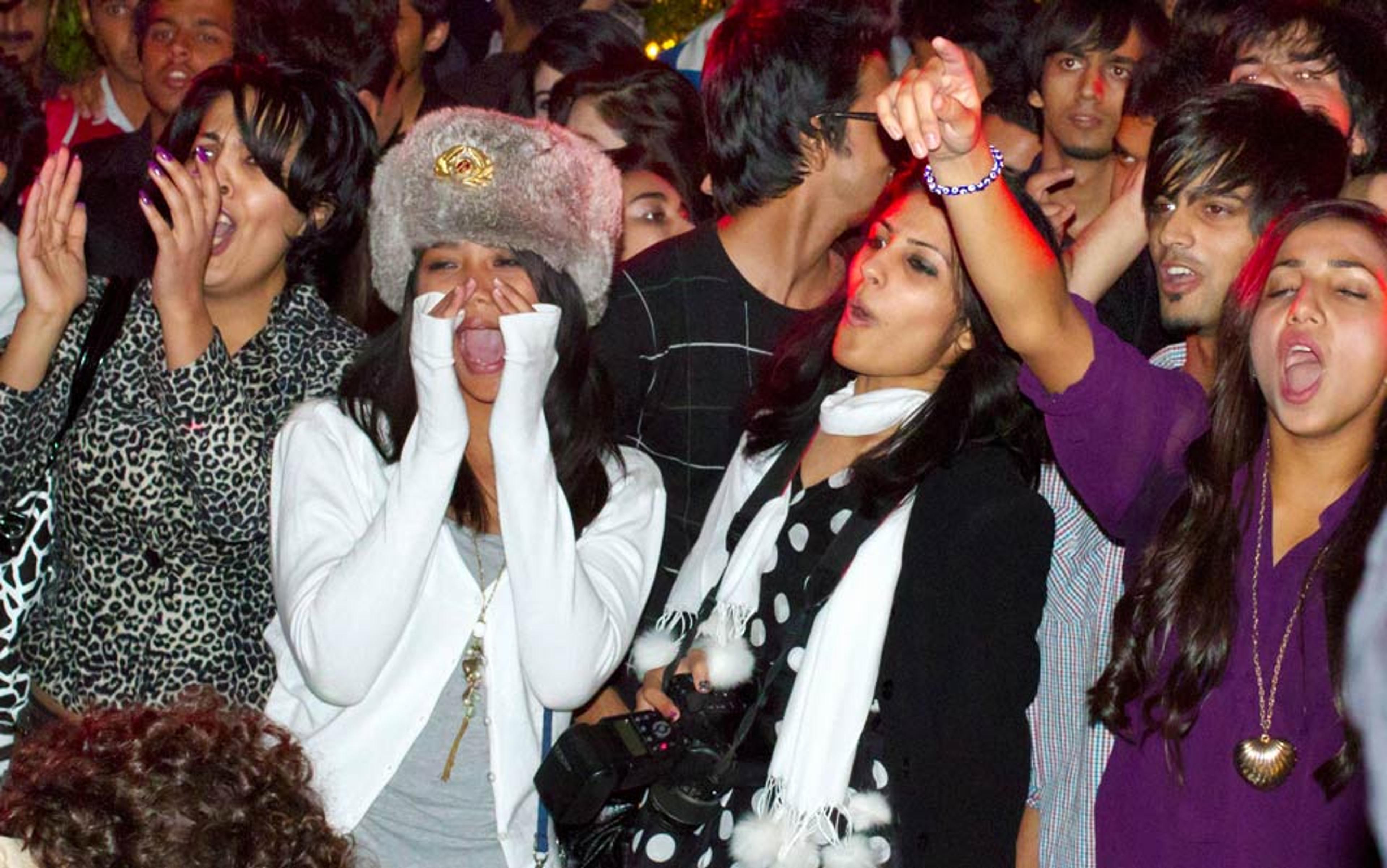

A little after midnight, I had walked out of the television studios after a current affairs live show. Each night my loquacious co-host, a good-humoured producer and his assistants would stand in the driveway for a milky cup of tea. The offices of Capital TV – a relatively liberal news channel set up in 2012 – were in a residential area of Pakistan’s capital. My foray into broadcast journalism came after years of writing and editing for a newspaper. The shift from earlier careers in government and international development was complete by now. I was in print, on the digital spaces, and finally on airwaves.

As we sipped tea, the show’s producer, a self-styled stand-up comedian, mimicked me and then blurted:

‘The show would get lots of rating tonight, Sir. You are too controversial now.’

‘Really?’ I asked; I had tried always to be moderate and cautious. ‘What did I say?’

‘Sir, you attack the Mullahs a bit too much, don’t spare the state agencies…’

‘Should I not?’

‘No, no, please do that, it’s good for the show’s rating. But remember, they will come after you.’

I laughed and walked out. As is the case in countries where labour is cheap, in Pakistan one has a professional driver. I reached the gate and there was no guard. Perhaps he had gone to make himself a cup of warm tea. Nor could I see my car. The boulevard, usually busy in the day, was silent. Across the road, there was a green belt visible in the pale streetlights. All one could hear was the sound of shrubs rustling in the night wind. I felt a little afraid.

What if there was someone hiding in the bushes waiting to attack me? Could it happen? After all, there are so many others – the fearless human‑rights advocate Asma Jahangir or the outspoken scientist Pervez Hoodbhoy – who hold anti-clergy views and criticise the abuse of religion. I chided myself like a rationalist against a fear that refused to go away. I went back and called (actually yelled at) the driver who had fallen asleep at home.

It was 2014. The long immigration lines at Abu Dhabi airport moved slowly. The last time I visited the US was 12 years before, a few months after the 11 September attacks, when I was an employee of the United Nations’ peacekeeping mission in Kosovo.

Now I felt far more anxious. I could not risk returning to Pakistan.

Too many people. Too slow. I sat with my two children, 13 and 11, who couldn’t understand why were we waiting hours, and I struggled with an explanation. We were not interviewed in time: our flight left on schedule.

What was it? The Muslim name? Bureaucratic slovenliness? Days and nights of insomnia, trepidation, regret and guilt had led me to this night – and I felt them all, all over again.

A few months earlier, I had moved to Pakistan’s second largest news channel – Express News – to host a current affairs show. Ten days before, as I left the Express Television Studios, a group of armed men on motorbikes attacked my car. I escaped more than a dozen bullets fired at my car.

When we turned off the busy Ferozepur Road onto the quieter Masood Farooqi Road leading to my home, they were waiting in a dark corner. I heard the tremors of a submachine gun. The flash of the bullets triggered my survival instinct. I leapt forward, huddling on the car’s floor. Later, I saw the bullet hole in its window: it would have been a precise shot had I not got down on the floor. Mustafa, my 25‑year‑old driver, together with a sturdy guard, sat in the front seats. The guard screamed: ‘Hamla ho gaya!’ (‘We have been attacked!’)

I could feel the warm blood. I wondered why there was no pain. Had the bullet travelled inside me?

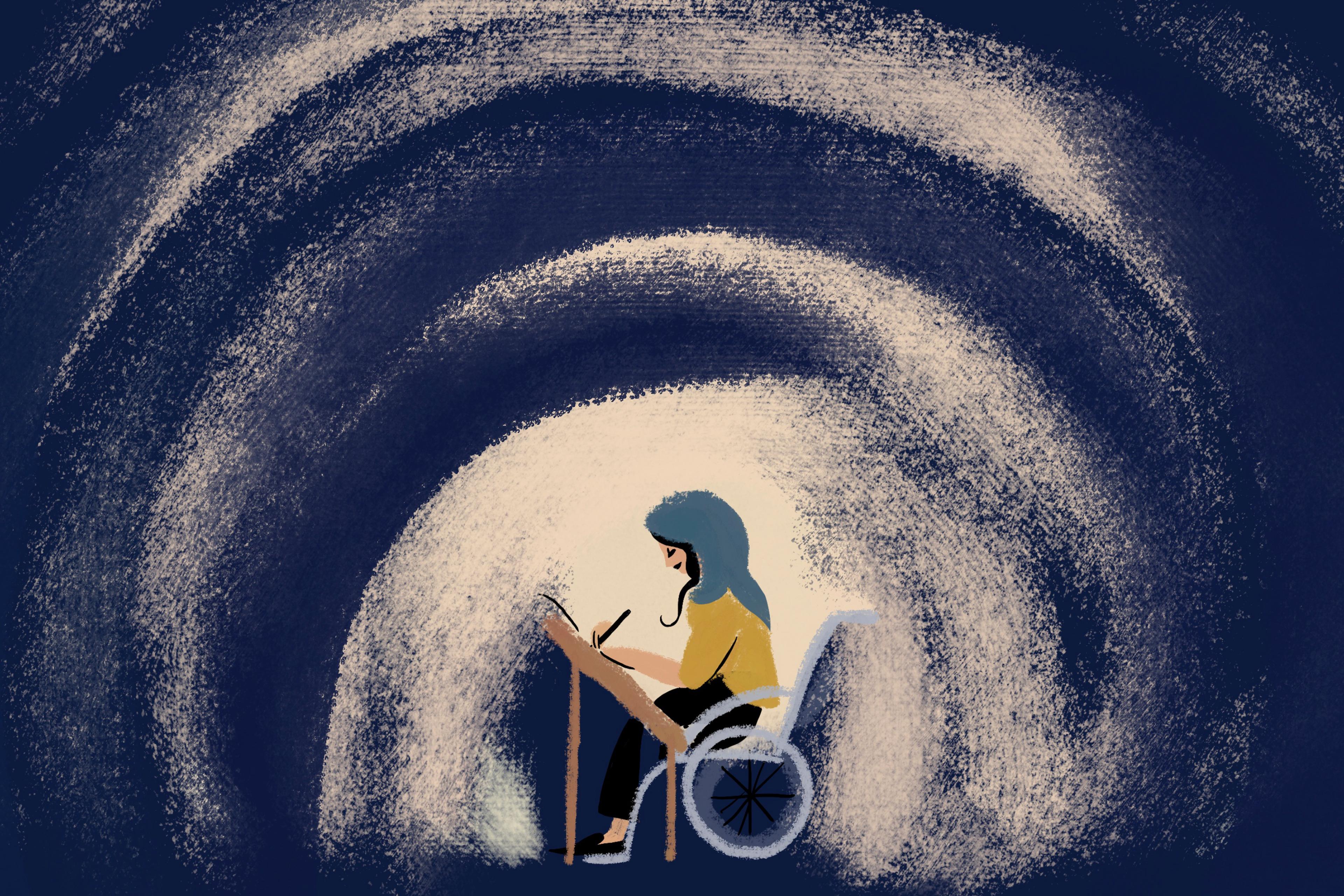

I tried to push my head under the driver’s seat and struggled to curl my legs under the passenger side, where the guard sat yelling. Security trainings from my UN and banking careers echoed. I thought first of death, then of being crippled for life. Bullets flew above me and I wondered if I’d end up with an artificial limb. I didn’t want to scream – it would alert the shooters that I was still alive – but whispered to Mustafa: ‘Drive fast, just get a little further and we will survive this.’

But the car just slowed down until it crashed into an electric pole. A bullet had hit Mustafa’s forehead: he was unconscious but the guard was still firing at the attackers with a puny pistol. Window glass was scattered over me. I lay silent, motionless, even when I heard the attackers leaving. Later, I learned that they’d feared entering into the light from the electrical pole, and had fled.

I could feel the warm blood. I wondered why there was no pain. Had the bullet travelled inside me? My guard was by now banging on the rear window. The crash had activated the auto-lock and he could not reach me. I pretended I was dead. What if they were still there, waiting? What if the guard was one of them…?

It was just before 9 pm. I heard the noise of an assembling crowd. Once it was loud enough, I got up from my feigned death. Splintered glass and bullet holes stared at me, as I felt the warmth of fresh blood.

It was Mustafa’s blood, blameless blood, and it had travelled under the car seat to drench me, seeping into my clothes. I am still drenched in it. I was still drenched in it sitting in the café at Abu Dhabi airport trying to run far away.

Islamabad gets cold in the winter. Sitting by the heater in February 2014, I was on the telephone for hours. Questioning, exploring, investigating. The Pakistani Taliban (also known as the TTP) had reportedly issued a list of media persons who had to be eliminated for the glory of ‘Islam’. This followed a 29-page fatwa which declared the media ‘party’ to the conflict in Pakistan, and accused journalists of siding with the ‘disbelievers’ against Muslims in the ‘war on Islam’ as well as of propagating secularism.

Jihad – that opaque term – required that all those who opposed talking to them for ‘peace’ be eliminated. I was first told of the list by a colleague. Others confirmed. Guilty as charged, I am a proud secularist. I panicked at first, and then bolstered myself with many coffee spoons of bravado. I employed a guard. I changed my routes frequently.

In an article for The Friday Times, partly spurred by the turn of events, I described the talks with the TTP as a ‘charade’, noting that in past weeks they and their affiliates were carrying out terrorist attacks with impunity. I’d written that the TTP had ‘supporters in the Punjab province namely Lashkar-e-Jhangvi [LeJ]’ and that ‘the space for Pakistani media and independent opinion has further shrunk due to the threats they face in reporting on the issue of Taliban and terrorism. At least three media houses have been attacked and the journalists face little or no protection from any quarter.’

Each time a Bangladeshi blogger is hacked to death, or a Saudi or Bahraini blogger is flogged or jailed, it hits me

Earlier, my work had invoked jidahists’ hatred on social media, where they are very comfortable and free. In December 2013, someone with a Taliban or ISIS flag accusing me on my Facebook page of ‘preaching’ a ‘secular ideology’ and ‘defaming mujahideen [jihadis] in every possible manner’. This person warned: ‘remember your end will be extremely bitter, the worst fate awaits the desi seculars like you. Your [sic] nothing more then [sic] a pure Western wannabe.’

Two verses from the Quran were cited:

Surah Ahzaab Verse 60-61: If the hypocrites and those in whose hearts there is a sickness and the scandal mongers in Madinah do not desist from their vile acts, We shall urge you to take action against them, and then they will hardly be able to stay in the city with you. They shall be cursed from all around and they shall be ruthlessly killed wherever they are seized.

I blocked the account, and posted the threatening message on my Facebook news feed. Each time a Bangladeshi blogger is hacked to death, or a Saudi or Bahraini blogger is flogged or jailed, it hits me. It’s all personal now.

Pakistan has a long history of muzzling dissent. Artists, writers, journalists and even the radical politicians have been censored, jailed and branded as ‘anti-state’ and ‘traitors’. Since the war on terror, the jihadist proxies – both pliant and rogue – have also turned into avengers of hurt pride and Islamic values. Often, the journalists are their targets. Sometimes, it is to send a message to others, but most of the time it is to silence. The jihadists operate with the complicity of the state.

From 2008 to 2015, 36 journalists were killed. Dozens more were attacked, threatened or harassed. In 2014, the International Federation of Journalists ranked Pakistan as the most dangerous country in the world for the news media. As a result, self-censorship prevails. Journalists do it to save their lives, and in many cases their jobs, too.

‘Don’t worry… we will put your loyalty to the test – So, get your pay-checks cleared for your family soon’

What makes a dissenter? In Pakistan, anything or everything. Since I started to write a decade ago, I took a few unpopular positions. Foremost was the issue of political Islam that has penetrated into the veins of Pakistani society almost like a drug, becoming indistinguishable from the idea of patriotism. The state did it as a marker of identity; generals and politicians did it to maximise power; and now dozens of militias – and even non-violent religious groups – compete for power and control using religion.

To counter this growing threat, I argued that Pakistan must change its policy toward India. Instead of portraying India as the infidel and existential, permanent enemy, why not work towards economic integration? Why not give up the idea of controlling Afghanistan via the proxy Taliban or some other political Islamist group, and work towards economic and political stability? Such views are at odds – sometimes unbridgeable – with a Pakistani state dominated by the military and civilian bureaucrats who peddle delusions of past grandeur of a Muslim Empire in India to preserve their power and untrammeled hold over public opinion. Pakistan’s identity as an Islamic Republic is a cash-cow for the state and for non-state actors, as it rallies public support and enables impunity for acts committed in the name of religion.

Writing in English was tolerable. But saying all this in the vernacular media is unforgivable and has to be avenged. So when I found my slice of the pop-media cosmos (including social media), it was found unacceptable. In October 2013, the anonymous user @maktal (meaning ‘guillotine’) tweeted threats at me. The first suggested that my name was on a list of individuals seen by Pakistan’s military forces as opposed to the Pakistani state: ‘@Razarumi u r also listed under Anti-State personnels, in Rawalpindi.’(Where the Pakistan Army headquarters are located.). A second said: ‘words don’t count in proving loyalty … it is blood.’ The final tweet was ominous: ‘don’t worry… we will put your loyalty to the test – So, get your pay-checks cleared for your family soon.’

The idea of testing loyalty with blood remains alien to me. It is the curse of modern nationalism built on medieval ideas steeped in religious supremacist discourses.

When the bloodletting came, it was not mine. It was poor, hapless Mustafa’s who left this world and me in it with an albatross of unresolved guilt, distress and regret.

Pakistan’s minority groups – the Shias, Ahmadis, Christians and Hindus - have borne the brunt of state Islamisation policies, which exclude them from the mainstream and also make them vulnerable to attacks by political Islamists, not unlike what is happening in Syria and Iraq. The justification for violence and discrimination comes from sectarian clerics who have historically been appeased by the state to aid the jihadist project in Afghanistan and Indian‑held Kashmir. To bolster Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan and Kashmir, the state empowers these groups, some of which wreak havoc on Pakistani society.

Since 2013, 43 attacks have targeted the Christian community, damaging scores of churches. Christians also face the spectre of the blasphemy law under which hundreds of non-Muslims and Muslims languish in jails. In 2013, I reported on an arson attack on a Christian settlement in Lahore’s Joseph Colony and suicide bombings at the All Saints Church in Peshawar.

Following the attacks on All Saints, a caller on my live show said that, while I was concerned about Christians dying in Pakistan, I seemed unmoved by Muslims getting killed by the West. On other occasions, live callers would tell me that I was speaking ‘against Islam’ and that I should be aware of the consequences. Occasionally, anonymous calls with threats were relayed. A junior staffer at one of the TV channels I worked with (who later resigned) threatened me that he knew the militant groups and would tell them that I was a freethinker. Inch by inch, my fear grew, but it was still exciting to challenge, to speak up.

My book’s title was misconstrued as a renunciation of my Pakistani identity. I had been branded ‘unpatriotic’

As a privileged Pakistani youth, I had opted to join my country’s Byzantine civil service, which still governs the ‘natives’ as in British-colonial days. I was a successful mandarin. Then, nearly a decade later, I joined the Asian Development Bank, which took me to Southeast Asia. Amid the travels, failed and functional projects, I realised how stories within me were blocked. Bureaucratic subservience meant, in these places, I could not be myself.

I started to write for Pakistani newspapers and anointed myself as Rumi, the poet’s follower. In 2006, I became one of the first Pakistani bloggers and found a much wider audience. Inspired by the legendary literary café, I set up an online portal for young Pakistani writers under the name Pak Tea House. By 2008, this nom de plume had to be reconciled with reality; I took sabbatical and joined the weekly newspaper The Friday Times as an editor. For the next few years, I wrote for multiple news outlets, commented on radio and television, and finished my book on India’s capital: Delhi by Heart: Impressions of a Pakistani Traveller (2013). Despite its success in the subcontinent and encouraging reviews, this book enraged some, as the title was misconstrued as a renunciation of my Pakistani identity. I had been branded ‘unpatriotic’.

From 2012, I was affiliated with a pro-democracy and human rights think tank, and worked as an editor, a columnist and later a TV host. This work enabled me to influence public opinion and policy. But Pakistan’s internal conflict, its state unwilling to rein in the jihad network, left me in a precarious milieu. I could write and talk about it at a cost of myself becoming a story, a target for abuse.

After the attack, I met a stream of police officials including the team investigating the case. They said that I could be attacked if I left my house. A team of guards protected my home, but Pakistani police are notoriously Islamicised, and I was scared. What if one thought I was a ‘heretic’ or a ‘blasphemer’, a Wajib ul Qatl (‘fit for murder’) – an Arabic term that has been popularised by political Islamists in Pakistan. I met the intelligence service (ISI) officials who gave me vague assurances of security. Later, a relative of a senior military official contacted me and mentioned that Jundallah, a Taliban group, had attacked me. These contradictory statements rattled me further.

I was told by many to invest in a bullet/bomb-proof SUV, and get additional security features in and around my home. I asked the Express TV CEO to arrange for an armoured vehicle if he wanted me to come to the studios. His silence was meaningful. My parents’ staff were threatened; and one night their domestic helper, on his way home, was stopped by two men and told that he needed to be careful after the fate of that driver.

My family, friends and some of my media colleagues were most supportive, but the media groups did not lend the kind of support needed to protect journalistic freedoms. They viewed me as an employee of Express TV and not as a media worker per se. Some suggested that the attack was fake and not meant to kill me. My anxiety and disappointment increased to such an extent that I could not sleep for days.

After I left Pakistan, the police arrested a group affiliated with the Taliban as my alleged attackers, and as the murderers of Mustafa. The case was tried in the civilian court until the end of 2014, then transferred to newly established and legally suspect military courts. One of the key actors, according to the police story, had been at large in UAE and was only recently nabbed. Why was he not arrested before, and even allowed to escape, when the police knew about his background? Such questions dog my nights and thicken the fog of confusion.

Furthermore, the families of the arrested group have been threatening Mustafa’s brothers and sisters. Very few media outlets in the country bothered to follow up my case. When the journalist Hamid Mir was attacked weeks later, the fissures in Pakistan’s media came into full exposure. Mir blamed ISI, and his channel was temporarily shut down. Rival media houses dubbed Mir a ‘traitor’, ostensibly under pressure from Pakistan’s secret services, which view criticism of armed forces and intelligence outfits as treason.

I am not bitter about Pakistan. I am simply petrified

The underlying dilemma is that state agencies and militant organisations operate with impunity. Intelligence outfits trained and fielded the Islamists to further their interests, but unleashed a variety of monsters, some of which have turned on their creators. The jihad network has thousands of members, operatives and handlers across the country. Since the attack on schoolchildren in December 2014, Pakistan has been fighting the militants, but skeptics say it is a partial effort or plain fiction. I think it is substantive policy shift but this is not a military battle. It requires a shift in identity and imagination by Pakistan’s elites and citizens.

I continue to get threatening messages on social media, including the warning from the Pakistani Taliban that they are monitoring me.

For years, I travelled across continents and lived, but the past 17 months are the longest I have not gone ‘home’. The idea of home has been altered for me. This is a scar that I have to live with. I am lucky to have some family and friends in the US, but being forcibly uprooted is a peculiar state of being. It sends you adrift on a sea of doubt. Leaving an over-engaged and productive life and starting afresh is not easy. But I have no choice.

The freedoms in the US have enabled me to rethink and re-evaluate my life and journey ahead. Many here have been supportive and have provided me with avenues to write, speak, reflect and engage with the policy and academic world. Most importantly, this liminal space is enabling me to heal, albeit slowly. The trauma has sort of sunk in and reflects every now and then. It makes me wonder if I would ever be the same person again.

I am not bitter about Pakistan. I am simply petrified. If another human being, on my account, might be hurt in even the most minor way, I would lose the tentative equilibrium I have regained. Let me be shameless and admit: I want to live. No cause in the world is worth my life.