We live in an age in which – for obvious reasons – it’s vital to understand how to build peace. Nuclear proliferation, inter-state and civil wars, terrorism and insurgencies, rising extremisms and hate crimes, social polarisation and increasingly vituperate online diction mean that learning how to reconcile enemies has never been more important.

This importance is widely recognised. Around $22 billion is spent annually by international donors on peacebuilding efforts. Since 2000, $10 billion has been spent in Colombia alone. The world’s second largest force deployed abroad – after the United States military – is the United Nation’s cohort of 100,000 peacekeepers, while internationalist organisations such as the World Bank and the Africa Union work alongside thousands of nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), diplomats, aid workers and research institutes to contain and reduce conflict.

It seems common sense that this epic, cooperative peacekeeping effort must have benevolent effects, and that it will be lauded across the political and ideological spectrums. In reality, however, there’s mounting evidence that it’s not the case: 40 per cent of all post-conflict arenas have reverted to violence within a decade, according to the economist Paul Collier at the University of Oxford. Half of ongoing wars have already lasted more than 20 years. Battle deaths have rocketed 277 per cent in the past 15 years. ‘Our templates and techniques for building lasting peace just don’t work,’ writes Séverine Autesserre, a political scientist at Columbia University in New York, in her book The Frontlines of Peace (2021).

The problem, according to Autesserre, is ‘the automatic, thoughtless use of templated, technocratic, top-down measures’. She cites a study in which leading experts analysed 21 peace accords: ‘There is not a single clear-cut example where deals among elites have actually ended violence. Trickle-down peace, it turns out, is just as fraught an ideology as trickle-down economics.’

One of her principal criticisms is the way in which ‘imposed’ peace resembles old-fashioned imperialism. She describes residents in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Palestine and Timor-Leste all complaining to her that ‘the interveners’ behaviours reminded them of what their parents or grandparents said colonialism felt like: demeaning, dehumanising, and infuriating.’

This is the result of what Roger Mac Ginty, professor in defence, development and diplomacy at Durham University, calls the ‘technocratic turn’ in peace-making: ‘the professionalisation of personnel, the standardisation of operating procedures, and the adoption and honing of “best practice”.’ It’s the business-management, box-ticking approach to peace in which expertise is exogenous: know-it-all first-worlders – who rarely speak the language and stay, briefly, in safe, secluded compounds – order how to fix things.

One of the obsessions of this model is democratic elections. But according to Autesserre, ‘democratisation is not an antidote to violence, but rather the opposite: it doubles the risk of civil war resumption’. Democratic elections produce, in the words of Collier, ‘a winner and a loser. And the loser is unreconciled.’ Even in peace processes that have been generally admired, as in Northern Ireland, democracy creates, according to Mac Ginty ‘increasingly polarised voting patterns’ and ‘ethnic outbidding’.

This ‘liberal peace’ has also been tarnished by its occasional imposition through violence, bringing to mind Mark Twain’s wistful quip about the US intervention in the Philippines at the end of the 19th century: ‘We have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them.’ The scorn for the foreign ‘peace-keepers’ extends to the UN since many of its peacekeepers have been accused of sexual violence. The UN’s Conduct and Discipline Unit has confirmed 700 rapes over the past 10 years, although some media reports suggest the real figure could be as high as 60,000.

It has also proved very difficult for cookie-cutter peacekeepers to comprehend the complexity of many conflicts. According to a 2018 report by the International Committee of the Red Cross, 44 per cent of conflicts involve between three and nine forces, and 22 per cent have more than 10. Some, such as the DRC and Libya, have hundreds. These multifaceted warzones are often simplified to oppositional binaries and, because negotiation is reduced to a few representatives around a table, it’s rarely inclusive. One UN study in 2012 found that, in 31 major peace processes, only 2.4 per cent of chief mediators, 4 per cent of signatories and 3.7 per cent of witnesses were women.

These superficial peace accords create what Jane Addams – one of the great theorists of peace in the early 20th century – called ‘negative peace’. It’s little more than a volatile truce. Traumas are often suppressed: because war had been based on the weaponisation of memory, this thin peace can survive only through the eradication of it. It’s coercive because often the very same militants who were forcing people to fight are now forcing them to make peace.

John Paul Lederach, professor emeritus of international peacebuilding at the University of Notre-Dame in Indiana and a senior fellow at Humanity United, is both an academic and an experienced peacebuilder at the coalface of dozens of conflicts. He says that this top-down peace creates an ‘authenticity gap’, leading to ‘suspicion, indifference, and distance’. In these circumstances, writes Duncan Morrow, a director of community engagement at Ulster University in Northern Ireland, ‘peace is presented as loss: a prison chosen as a least worst option not the miraculous opportunity of escape.’

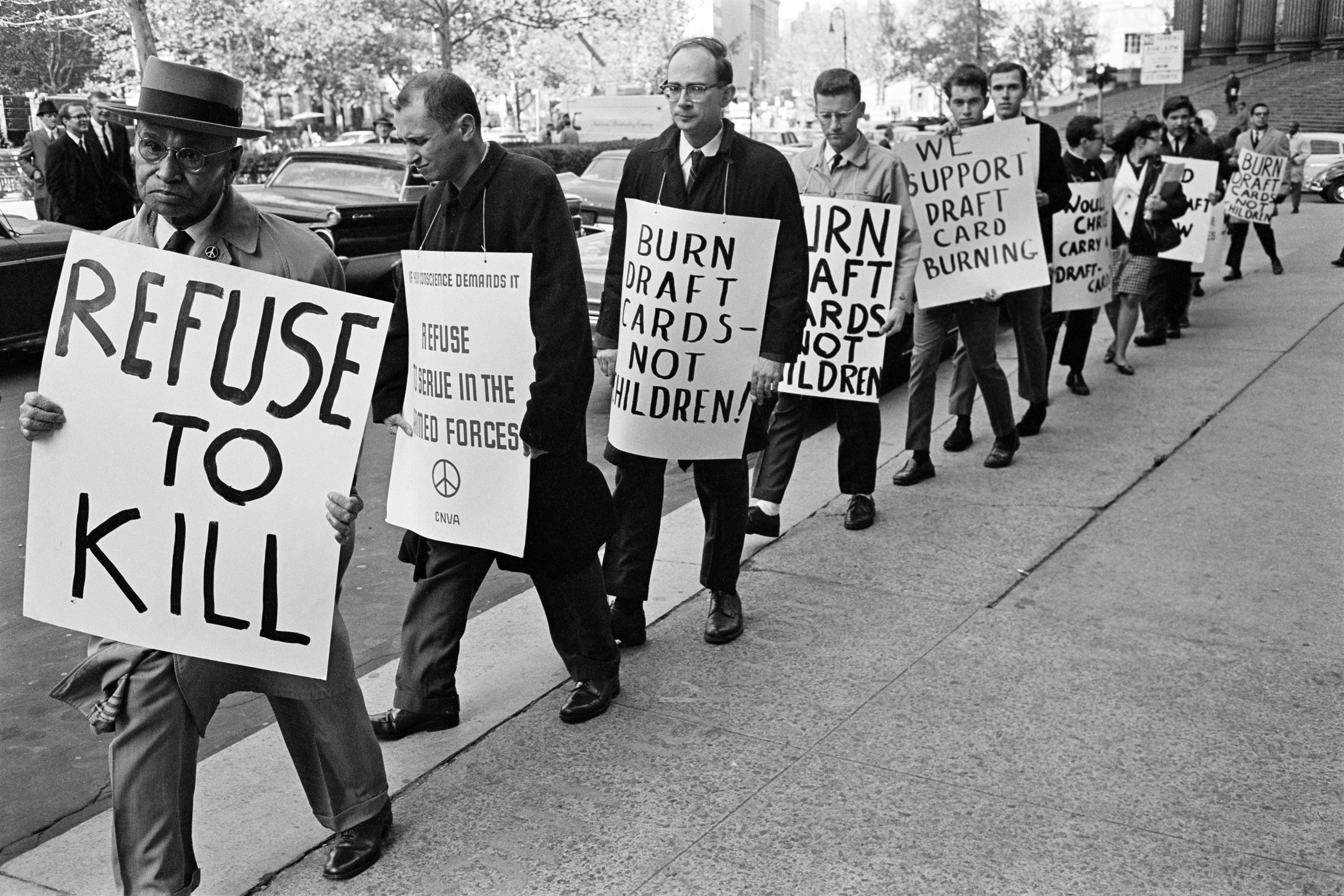

‘Peaceniks’ are used to societal scorn. They have always stood accused of naivety because, cynics say, violence is intrinsic to human nature: we’re nothing more than aggressive primates fighting for resources and power. That position was challenged in the immediate postwar years not only by Mohandas Gandhi’s pacific campaign against the British empire, but also by the realisation that, if the primates now had nuclear arsenals, there could no longer be a meaningful winner in warfare.

So, having studied war for centuries, people began to study peace. The first undergraduate programme was initiated in the US, in Indiana, in 1948. Often the impetus came from Scandinavia: in 1959, Johan Galtung (one of the leading lights of peace studies) co-founded the Peace Research Institute in Norway and, in 1963, the Peace Research (later ‘Science’) Society was founded in Sweden. By the mid-1970s, the word ‘irenology’ (the study of peace) had entered dictionaries.

As a formal, academic pursuit, it had many disadvantages. Peace studies was suspect to rigorous scientists because it often seemed speculative: not an analysis of what is, but what might be. It seemed to be about studying a project, or a process, not an object. It was often associated with progressive politics (decolonisation and the civil rights movement) and radical Christians (Quakers and Anabaptists) on whom traditionalists looked with alarm.

Latent attitudes – requiring reconciliation and healing (peacebuilding) – have often been ignored

But for many, this nascent discipline was extraordinarily creative and exciting. It seemed to draw on a rich variety of academic disciplines, including anthropology, psychology, sociology, history, religious studies, criminology, security studies and so on. Peace studies had – in an age of nuclear proliferation and postcolonial wars – an urgent and practical application.

But the end of the Cold War radically changed the discipline. New countries and civil conflicts emerged from the disintegration of the old order and encouraged many northern hemisphere leaders to become messianic, liberal interventionists. ‘Peace studies became not only a bona fide academic discipline, but also a field of practice,’ says Mac Ginty. There were huge investments, and peace scholars were drawn into the overlapping fields of conflict-resolution, state-building, development and security. Although it seemed like the apotheosis of the profession, many felt it was akin to the Roman emperor Constantine’s co-option of Christianity.

Investments and personnel were concentrated on only two of the three corners of the ‘conflict triangle’. Conceived by Galtung in 1969, and frequently emulated and altered, the triangle offers an ABC to understand conflict: attitudes, behaviour and context. While the ‘context’ requires diplomatic intervention (peace-making), and ‘behaviour’ needs monitors and enforcement (peacekeeping), the latent, diffused ‘attitudes’ corner – requiring reconciliation and healing (peacebuilding) – has often been ignored.

Peacebuilding is the much more inclusive, fuzzy, even mysterious side of peace studies. There were many examples of it in Northern Ireland. Ray Davey – a chaplain and prisoner-of-war in Germany who witnessed, first-hand, the bombing of Dresden in 1945 – set up the Corrymeela Community in 1965. Joe Parker, a fellow cleric who lost a son in the ‘Bloody Friday’ bombings of July 1972, created the movement Witness for Peace. Most famously, Women for Peace (subsequently, the Community of Peace People) came into being in 1976 after a getaway driver for the paramilitary Irish Republican Army (IRA) was shot by the British Army and his swerving car killed three children passing by.

But very often peacebuilding initiatives were anonymous and unseen. In 1983, John Lampen, an English Quaker, moved to Derry in Northern Ireland. A year later, he was joined by his wife, Diana, and their children. The Lampens were inspired by the work of another Quaker, Will Warren, who had lived in Derry for many years and had quietly befriended both sides in the conflict, including various members of the rival paramilitaries.

Warren once said that his role as peacebuilder had been ‘to listen to people on both sides … and maybe, one day, to help them to listen to one another’. Listening was the central element of Quaker peacebuilding. Adam Curle, who was the inaugural professor at the hugely influential Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, wrote in True Justice (1981):

The importance of listening, then, is that we not only ‘hear’ the other in a profound sense but communicate with him or her through our true nature. This in turn evokes a response from the true part of her or his nature … That is why peacemakers should learn to listen as attentively and as constantly as possible. They not only discover what may be vital to know, but they reach the part of the other person that is really able to make peace, both inwardly and outwardly.

So the Lampens listened a lot and planned little. Through slowly meeting people, they realised how much the violence was provoked by grief that was caused, in turn, by violence. Choosing to be with all sides, rather than denounce them, was a way to break that cycle. ‘Hurt only heals when it’s heard,’ says John Lampen. They became close friends with Martin McGuinness (the former IRA member who was later a deputy first minister of Northern Ireland): ‘We had to hear some of his hurt – the bayonet into the stomach of his friend and so on. We just had to be there to understand.’

They were able to convey messages from one side to the other in ‘the Derry experiment’

They were part of the Peace and Reconciliation Group (PRG) in Derry. Often what they were doing was a gentle dismantling of barriers. There was a Quaker Youth Theatre that deliberately went into both Catholic and Protestant housing estates and, even, the British Army barracks. They organised a neighbourhood festival on derelict ground and invited musicians and sportsmen and women from all sides. Their peace group minibus deliberately used to pick up and drop off Catholics and Protestants so that they both saw the other’s community, their estates, shops, churches and schools. ‘Often,’ remembers Diana Lampen, ‘they would look out of the window and say: “Oh, it’s just like our place.”’

It was a practical application of what the US psychologist Gordon Allport in the 1950s called the ‘contact hypothesis’, his notion that border crossings could reduce prejudice. Diana Lampen took women to retreats at Corrymeela and recalls that they, from either side, stayed up until dawn drinking tea and finding common ground.

But as well as making low-key connections, the Lampens also became vital conduits between the British Army and the IRA. Before becoming a Quaker, John Lampen had been a soldier engaged in ‘internal security’ operations during the insurgency in Cyprus, so he understood the military and was accepted by them. As well as being close with McGuinness (a Catholic), the Lampens were also friends with Gusty Spence, a Protestant and a former leader of the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force, who’d also been in Cyprus. They were able to convey messages and complaints from one side to the other in what became known as ‘the Derry experiment’.

The Lampens and the PRG were using a technique pioneered by the US psychologist Charles E Osgood. His so-called GRIT method was a de-escalation strategy in which reciprocal concessions were made. Over time, as specific requests were met, trust was built even if the two sides were never directly talking to each other. The Lampens took the community’s concerns to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (the police force in Northern Ireland) and to the British Army: that the use of helmets instead of berets made the streets appear ever more militarised; that the use of telescopic sights to scan the streets added to citizens’ sense of being in the crosshairs; that civilians were being mistreated by police and Army. The Lampens set up seminars for soldiers to understand the issues.

Messages also went the other way: the Army was alarmed at the new use of coffee-jar bombs filled with Semtex explosives that were indistinguishable from the other (empty) jars and bottles that were frequently thrown. Their retaliation could cost innocent lives, and thus intensify hostilities, if they mistook one for the other. The message was taken to the IRA and, in Derry at least, the coffee-jar bombs weren’t used again. Later, larger issues were addressed and ‘the Derry experiment’ became the precursor to the formal peace talks.

Those fragile beginnings of peace were sometimes harder for combatants than warfare, because they were no longer lamenting what others had done to them, but what they had done to others. The Lampens began to realise that an important part of their work ‘was to be alongside them [former militants] as they faced alcoholism and depression, remorse for deeds done …’ Morrow, a longtime observer of the Northern Ireland peace process, wrote in 2016 that ‘far from being romantic, reconciliation is always a shocking apocalypse of both mercy and truth. Generosity shines a more penetrating and unbearable light on our complicity with violence than conflict.’ A forgotten component of the peacebuilder’s role is to help militants make peace not just with each other but also with themselves.

None of which detracts from the obvious need for what are usually called ‘track one’ activities – the elite-level negotiations and accords. They can, clearly, encourage or enforce formal disarmament and public disavowals of violence; they create or repair civil institutions and provide a context of ‘consociationalism’ (power-sharing) all of which allow ‘track two’ citizen peacebuilding to flourish. The criticism arises because top-down peacebuilding soaks up almost all the available diplomatic, political and economic capital, as well as drawing the lion’s share of media attention on account of producing a standardised narrative of a peace out of a complex, multifaceted reality.

But those two tracks are, ideally, complementary: theorists of peacebuilding often refer to Lederach’s top-down, bottom-up pyramid described in his book Building Peace (1997), which can create the desired ‘middle-out’, or what Addams poetically called ‘lateral progress’. And it’s noticeable that the emissaries of elitist peacebuilding often learn precisely the same lessons as those on the ground: in his book Great Hatred, Little Room (1999), on the endless calls and meetings that led to the Good Friday agreement that ended the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the former UK government adviser Jonathan Powell wrote that ‘the most important aspect … by a long way … was the personal relationship between the leaders.’

Being in turbulent settings, many peacebuilders mention the need for an inner stillness, what Hindus would call ‘shanti’. Jonathan Herbert is a lifelong peacebuilder and has worked in conflicts in the Solomon Islands, Israel-Palestine and Uganda. ‘For me, in Palestine,’ he says, ‘the biggest thing was having to come to terms with so much conflict within myself. I had taken on the pain of Palestinian friends and had seen so many horrible rights abuses – kids handcuffed and traumatised, old men beaten up. I felt polluted by the place, by the hatred. I had to look at myself, and go and reflect and find compassion for Israel. That’s what reconciliation is about: making peace with ourselves first, then with others…’

It’s a question, he says, of quietly observing what the conflict is doing to you before you can ponder the opposite, what you might do to it. Rather than be active, you have to slow down and see what moves in and around you. ‘A lot of it is about listening,’ says Herbert, ‘listening to people, but also listening to yourself to find your balance.’

It requires the sort of humility that isn’t often found among problem-solving peacekeepers. ‘It’s about presence,’ says Herbert, ‘about just living in an area of conflict and learning the language. You have to dare to be fairly useless to begin with, dare not to get anything out of it…’ As one’s perspective on the violence becomes much more local, both conflict and peace start to be framed very differently. In Israel, it becomes about not only the twin tragedies of the Shoah and the Nakba, but about far smaller, sometimes even remediable issues: access to olive groves, to running water, to relatives and to education.

In order to understand peace on locals’ terms, Mac Ginty and his colleague Pamina Firchow devised what they call ‘everyday peace indicators’. Rather than the slightly absurd parameters often used to evaluate pacification, they found that the real indices of peace were, for locals, often far more mundane: a lack of barking dogs, a child using the future tense, the ability to sleep in pyjamas, put up an antenna on the roof, or urinate outside at night. Bruno Hussar, the founder of Wahat al-Salam/Neve Shalom, a peace community in Israel, once said that there were, for him, two clear indicators that his community was finally creating peace: ‘the children and the trees… That’s life; life coming up.’

The path to peace isn’t a question of eradicating the trauma but using it differently

Very often ‘peace communities’ like Hussar’s are experimental incubators of what might work in society at large. Rondine – a ‘peace citadel’ in the Tuscan countryside – brings together young Israelis and Palestinians (as well as many other warring nationalities) for two-year residencies. The community’s founder, Franco Vaccari, is a psychotherapist and teacher, and, although he says that Rondine is an ‘experiment or hypothesis’, he mentions one vital point of departure: the removal of ‘fantasised presences’, those notions we have about the enemy that dehumanise them. ‘The concept of the enemy,’ Vaccari tells me, ‘poisons the relationships of anyone who has lived through war, but it’s dormant within all our relationships.’

Peacebuilding is also hampered if conflict is erased rather than observed. According to Paul Hutchinson, a mediator and former centre director of Corrymeela in Northern Ireland, ‘you make a faulty peace if you think conflict is bad.’ The classic playground intervention – ‘Say sorry, shake hands’ – is counterproductive, he says: ‘Culturally, the West doesn’t know where to put conflict other than in the bin or under the carpet. So conflict is avoided as opposed to being seen as revealing about the relationship. It has the potential for learning.’

Part of that learning often involves the recognition of a community’s or an individual’s ‘chosen trauma’. Prevalent in therapeutic circles, this concept has been applied to conflict situations by, among others, Vamik Volkan, a Cypriot peacebuilder and psychiatrist. It suggests that a group’s identity relies upon a collective memory of a profound violation that often serves as the justification for their own violence and revenge. The path to peace isn’t a question of eradicating the trauma but using it differently. As Hussar once said in an interview: ‘What do we do with the memory of the Holocaust?’

‘Communicating one’s own pain is the turning point,’ writes Vaccari in his book Metodo Rondine (2018), or ‘The Rondine Method’. At Rondine, they use a weaver’s shuttle, and ‘enemies’ take it in turns to pass it to each other across the loom and express their grief. The transformation is, writes Vaccari, sometimes very slow, sometimes sudden: ‘The person once considered the most distant is now the closest … : “No one else can understand my pain better!” … The suffering is simply symmetrical … now, in the presence of the new protective relationship, pain becomes a shared sensation.’

It’s an inversion of Sigmund Freud’s notion of the ‘narcissism of small differences’, the idea that very similar peoples exaggerate their separateness. It happens in many warzones but at Rondine, instead of magnifying the differences, they discover similarities: it’s what one Azeri participant at Rondine called ‘discovering oneself within the other’. Another participant, an Israeli, said: ‘My enemy’s heart is the Promised Land.’ These aren’t trite lines, but epiphanies that emerge only after a year or two of intense and painful accompaniment at Rondine. Participants then return to their own countries as ambassadors of peace, trying to rehumanise their enemies for their own communities and holding on to the paradox – expressed by Vaccari – that ‘the more I’m bound, the more I’m free.’

Peacebuilders are often searching for metaphors to understand the mysterious process they’re engaged in. Addams spoke of ‘peaceweaving’, and in their admiring essay about her, the political scientists Patricia M Shields and Joseph Soeters in 2015 wrote of why it’s an apt metaphor: ‘individual, often fragile, strings are connected through the process of weaving, which does not homogenise the combined, often colourful, strings but lets them work together despite their differences.’ Diana Lampen calls peacebuilding a spider’s web: there are delicate links in all directions with, at the centre, not a spider but peace itself.

It’s noticeable how often the natural world – its adaptability and fragility – is invoked as a metaphor. In attempting to imagine a more inclusive metaphor than the cliché of the negotiating table (with its very limited participants), Lederach talks of ‘stigmergy’. It’s the technical term for the scent left by insects as they travel, enabling itinerance and interaction to create order without centralised commands. He eulogises: ‘The trace of a thousand conversations … spider-like travelling, moving across communities and locations to spend time in collective, repeated, sustained and … open conversations.’

Many express a sort of powerlessness. Stephen Ruttle is a QC who is one of the UK’s foremost legal mediators. In his previous incarnation as an adversarial lawyer, his work was, he says, ‘very linear, very logical. Words were bullets. But mediation is a control freak’s nightmare,’ he says, laughing. ‘You just don’t know what’s going to happen next. Words are building blocks, and mediation has no goal in mind other than the next conversation.’

Nothing can be forced. Autesserre writes that ‘the process is just as important as the outcome’, and many bottom-up peacebuilders are suspicious of the directional commands of the ‘roadmap’ cliché. They talk instead of platforms, of spaces that are more about experiences than results, where there is space for intuition, chance, observation and encounter. Morrow, in writing about Corrymeela, said: ‘There was no grand plan, only steps. There was no political blueprint …’ That lack of control occurs because of the innate fragility and vulnerability of the vital filaments on the spider’s web: relationships that can’t be legislated, quantified or enforced.

Lederach says that ‘the ability to sense the humanness of another begins with attending.’ For him, ‘to attend’ encapsulates the role of the peacebuilder because it implies not only waiting on someone, being attentive and attuned to them, but also, etymologically, being stretched and made sensitive (‘to attend’ is linked to ‘tenderness’). It’s similar diction used by R S Thomas in ‘Tell Us’, his poem about bridging polarities, where he writes of a stretching so extreme that it raises ‘the possibility of dislocation’. This need for sensitivity means that the peacebuilder is, according to Lederach, far more artist than technician: ‘unveiling, releasing and unleashing potential to bring into existence what does not now exist’, offering what the poet Seamus Heaney called ‘a glimpsed alternative’.

You’re more like a window through which the opposing sides can see each other

If it’s true that peacebuilding requires not esoteric learning but sacrifice, sensitivity and artistry, it might be that we’re closer than expected to what Mac Ginty in 2014 called ‘the elixir’ of peacebuilding: ‘local ownership’. Not in the sense that locals accept what’s cooked up for them, but that they actually create their own recipes for peace. Many scholars, such as Oliver Kaplan at the University of Denver, have begun studying pockets of spontaneous peace initiatives in places that had been discounted as conflict zones: the San José de Apartadó village in Colombia, founded in 1997, with its simple rules (‘Don’t carry arms’); the Association of Peasant Workers of Carare (ATCC), founded in 1987, also in Colombia, whose philosophy is encapsulated in the line ‘We shall die before we kill’; the village in South Kivu, in the DRC, where microloans have created cottage industries drying bricks, refining cassava flour and brewing beer; the autonomous peace initiatives in the Republic of Somaliland and on the island of Idjwi in the DRC.

What’s interesting is that those local peace projects have discovered almost identical rules around peacebuilding to their learned counterparts. One of the clauses of the ATCC manifesto says: ‘Talk and negotiate with everyone.’ They, like the Quakers, put a premium on veracity and transparency, what Gandhi called satyagraha, or ‘holding on to truth’. Like him, many have paid with their lives for their idealism: the founder of ATCC, Josué Vargas, was murdered in 1990, and eight people were killed in San José de Apartadó in 2005.

Peacebuilding is inherently risky. Roy Calvocoressi, the late founder of the Christian International Peace Service (CHIPS), used to talk about ‘bearing the enmity’, when you’re stuck in the middle, untrusted and scapegoated. ‘It can feel like an attack,’ says Hutchinson. It requires almost a self-emptying (what Christians would call ‘kenosis’) so that you’re more like a window through which the opposing sides can see each other. You’re present, but also, somehow, absent.

Accepting the risks is part of the role: ‘If the police, soldiers and paramilitaries were risking their lives in the cause of war,’ says Diana Lampen, ‘full-time peacemakers had to be prepared to risk theirs in the cause of peace.’ She was, briefly, taken hostage by paramilitaries but found them metaphorically disarmed because she was neither fearful nor aggressive. ‘That’s the power of the powerless,’ she says.

Despite such vulnerabilities, very often the professional peacebuilders learn from these vernacular projects: Lederach, considered by many a global guru of peacebuilding, often writes in his books how he learns from those on the ground, not vice versa, particularly around the notions of collective narratives and the meaning of memory and of the land. ‘This work,’ says Herbert, ‘gives you a more indigenous way of looking at things: not that resources are scarce and we have to fight for them, but that the world is full of abundance if we respect it and share the fruits.’

Clearly, troubled conflict zones still, often, require outside mediators. But the most admired of them – such as the Life and Peace Institute based in Sweden or the global RESOLVE Network, don’t hubristically impose their own roadmap, what Hutchinson jokingly calls ‘mediation jujitsu’, but listen, curate and facilitate conversations. It raises the uplifting notion that peace is far more egalitarian than war, requiring not expensive arms, but simply the freely available, sometimes suppressed human spirit.