Listen to this essay

20 minute listen

War is as old as humanity. Long before it became a matter of law or strategy, it was written into our myths and instincts: the urge to dominate, the struggle for survival, the fall from paradise into conflict. As the author Robert Ardrey once observed, we are not only animals; we are armed ones.

In modern times, the reality of war has become impossible to ignore. The photographs of Hiroshima’s ruins, the televised images from the Vietnam War, the viral pictures from the Bucha massacre in Ukraine and the latest livestreamed bombardments of Gaza all make clear what earlier generations could more easily conceal or forget. War is not only the threat of violence. It is the collapse of moral and political order: a moment when the rules of coexistence fall apart, laws twist into something else, and human life loses its value, or takes on a new one.

Yet even in such devastation, responsibility does not disappear. To inherit war is to inherit the responsibility to restrain it. In democracies, that burden is said to be shared – rooted in consent, exercised through representation. And still, while war may be as old as humanity, democracy is not, and that difference reshapes the questions citizens must ask.

What happens when the gravest of political acts – the decision to kill – is taken without the citizens’ assent? That is the paradox of what I call the silent mandate: leaders treat the people’s silence, which is structurally imposed, as if it were consent, turning absence into acquiescence. It is the point where democracy keeps its name but loses its meaning. If conflict is the most serious act a political community can undertake, shouldn’t it face a higher bar than ordinary political decisions in a democratic state? And even if a conflict seems to meet the conditions of a ‘just war’ – if such a thing exists – it may still be illegitimate if those in whose name it is fought were never asked.

In democracies, wars are rarely directly fought by civil society itself, but they are financed by it, and money carries its own moral weight. The decision is made not on the battlefield but within institutions that claim to speak for the people while avoiding their voice. Some doctrines allow for war in so-called ‘supreme emergencies’. But can such reasoning ever suffice in a democracy, where legitimacy should flow from the will of the people? Such silence is dangerous. It binds us, citizens, to the consequences of war while denying us any role in deciding whether it should be waged.

When violence is carried out in our name but without our voice, what kind of democracy remains?

This kind of democratic deficit is not new. In modern democracy, the United States offers perhaps one of the most emblematic cases of a recurring paradox: a democracy that, at the height of its power, exposes the fragility of its own principle. Among the many moments that reveal it, none is more telling than the US president Harry S Truman’s decision in 1945 to use the atomic bomb. Although the US Constitution grants Congress the power to deliberate on matters of war, the conflict with Japan had been declared years earlier, and Truman was under no legal obligation to seek a new authorisation. But that does not change the substance of the matter. A decision of such magnitude, the use of a weapon capable of erasing entire cities, should have required, at least to my mind, a broader sense of responsibility, a gesture of accountability no less than toward the institutions that claimed to represent the people.

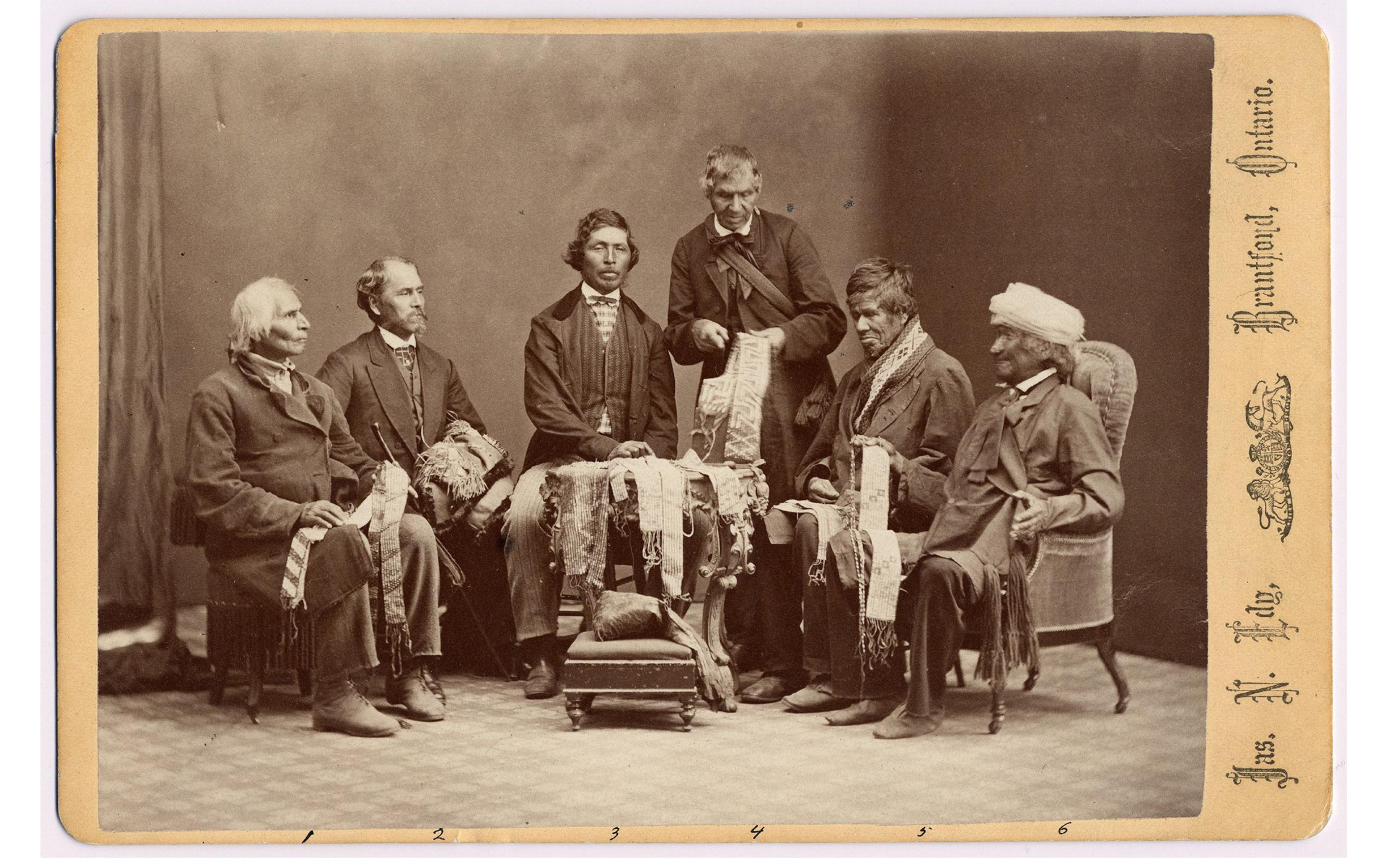

Telegram from the US Secretary of War Henry Stimson asking for Truman’s permission to release a public statement announcing the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, 30 July 1945.

On the reverse is Truman’s handwritten reply authorising the release of the statement with the remark ‘release when ready’. Images courtesy the National Archives

Yet, no record exists of any dialogue with US Congress and certainly not of any public debate. One of the most irreversible choices in human history was made by a single man, probably with the support of a handful of advisers, and formalised in a brief handwritten note during the Potsdam Conference. In that note, addressed to the US Secretary of War, Truman authorised the release of a public statement with the remark ‘release when ready’. Those three words, written in the margin of a communiqué, have often been read by history as the final seal on Hiroshima. Everything happened in the silence of institutions and, even more profoundly, in the silence of citizens. The decision did not pass through the US Congress but through the president’s own conscience. Only after Hiroshima did Truman turn to Congress, not to justify his act but to propose the creation of an Atomic Energy Commission. Crucially, it was a gesture that borders on irony. However, that moment marked a point of no return: the atomic bomb entered history not with public justification, but with the quiet efficiency of routine.

At first glance, this might seem a modern failure of democracy, a symptom of institutions that have drifted away from their people. But the logic runs deeper. The idea that leaders can decide on war without consulting those who will bear its costs is far older than democracy itself. It stems from a moral inheritance that has shaped political authority for centuries, teaching rulers to frame violence as duty and obedience as virtue. What I now call a ‘democratic deficit’ is, in truth, the echo of that ancient order: a way of justifying force while keeping power in a privilege of the powerful.

The legitimacy of war depended on reason and principles that all people, in theory, could grasp

Before it became a matter of politics, conflict was made thinkable through stories that tried to make it seem right. The moral vocabulary of war began to take shape early. The first Christians, once fiercely pacifist, gradually learned to reconcile faith with force. After Constantine made their faith the creed of the Roman Empire, the Church struck a bargain with power. Armies and generals could not be wished out of existence, so war was reimagined as tragic but sometimes righteous, a bitter response to a broken world. It was Augustine of Hippo who gave this new reality its language, later distilled into the bellum iustum or just war theory. What mattered, accordingly, was the purpose.

A conflict could be acceptable if it restored peace, punished injustice or defended the weak. It had to be guided by necessity, not ambition, and tempered with mercy even for the defeated. From this moral balancing act, the roots of what we now call the laws of war began to grow. More than a thousand years later, Europe was burning with religious conflict. Armies of Catholics and Protestants ravaged each other’s lands in brutal cycles of revenge. Out of this chaos came Hugo Grotius, a 17th-century Dutch jurist who tried to strip war of its theological frame, arguing that the rules of a battle rested not on divine revelation but on reason itself. Grotius dared to suggest that, though it would be wicked to assume it, even if God did not exist, the norms of justice would still hold. With that single claim, he offered the foundations of a secular international order, where the legitimacy of war depended on reason and principles that all people, in theory, could grasp.

Here the problem lies in the fact that these ideas on the justification of a conflict, however influential, were not born in democracies. They came from kingdoms, empires and the shadow of divine right. In those worlds, the question of who had the authority to declare war was never posed in democratic terms. And this is where much of the moral tradition – despite its conceptual richness – falls short of the democratic ideal. Today, we have inherited sophisticated debates about what makes a war just: whether there is a just cause, such as self-defence, and whether it is pursued with the right intention. What remains unexamined is the power to decide, that is, the right to turn judgment into action. For centuries, the moral burden of ferocity was carried by rulers. But, in a democracy, it ought to be carried by the people.

A first, cautious attempt to update the old theory of just war came centuries later. Yet the same logic returned in new forms, and modern democracies inherited the language of just war without its democratic correction. In the 20th century, several thinkers returned to that old moral tradition, seeking to make sense of it in a democratic world, none more influential than Michael Walzer. Writing in the long shadow of the Second World War, Walzer introduced the idea of a ‘supreme emergency’, a situation so catastrophic that even the moral rules meant to restrain war might have to break. In Just and Unjust Wars (1977), he argued that, when a community faces ‘an ultimate threat to everything decent in our lives,’ leaders might feel compelled to cross boundaries that would otherwise remain sacred. What is normally forbidden, such as bombing civilians, becomes permissible. Walzer’s honesty was bracing, almost ethically arresting. He refused to let leaders off the hook. Even in such moments, he wrote, they are still guilty. They remain moral criminals, even if their crime is necessary. The doctrine shocks because it names the unbearable tension between human rights and human survival. But it also reveals a danger. Once the door to exceptions is opened, who can be sure it will ever close again?

As our thinking about war grew more refined, it became wiser, more rational, and somehow still blind to the right of those who would live with its consequences to have a say. Over time, that moral oversight hardened into political habit. What fails today is not just leadership but the very design of democratic power, a structure that learned to justify war without ever learning how to share its choice. This failure is not accidental. It is built into the way democracy came to organise power. Modern representative systems replaced the monarch’s divine right with the citizen’s vote, but they preserved the same logic of distance between those who decide and those who obey. Understanding why this distance endures means looking back to the origins of representation itself, to the moment when citizens first learned to entrust their power to others. Delegation was never meant just to make government more efficient. It was born as a safeguard against confusion, a pact – a social contract – to prevent society from tearing itself apart. By agreeing to transfer the monopoly of force to the state, people renounced not only the right to act violently but also the power to decide when that violence might return. It was an act of trust born from fear, the hope that authority could channel chaos into order.

The same democracies that promise never to turn their weapons on each other continue to fund distant conflicts

Representation, in this sense, is both a triumph and a paradox. It is what makes democracy possible in large societies – still, it also introduces an inevitable distance between those who govern and those who are governed. Elections, in fact, are not mirrors; they do not perfectly reflect the people’s will. They produce trustees, not delegates. This imperfection is not a flaw to be corrected but a condition that makes democracy itself possible. Still, I cannot help asking how far this distance can stretch. Can we really treat the decision to go to war as we would a tax reform, a transport plan or a healthcare bill? Those kinds of decisions are reversible, limited in scope, and accountable to voters. War is unlike any other act of government; it converts the wealth of a society into tools of death and decides whose lives will be spent for it.

Modern democracies like to believe, and like to repeat, that they have outgrown war, at least among themselves. And, to some extent, it is true: they no longer fight one another directly. The theory of ‘democratic peace’, as it is called, as a matter of fact holds on paper. Yet peace at home often conceals conflict abroad. The same democracies that promise never to turn their weapons on each other continue to fund distant conflicts, supply arms, and sustain alliances. By shifting the theatre of a battle, they keep fighting, sometimes by proxy, instead of working to bring wars to an end.

Wars fought abroad remain and have remained, in a substantive sense, wars of democratic states. It is a bitter contradiction, especially if we remember that the birth of most of today’s democracies, and later the creation of the United Nations, was also meant to mark the beginning of an order built on peace. Seen from this perspective, the notion of ‘democratic peace’ is not a shield against responsibility, but a reminder that democracies, too, bear the weight of the wars they wage. It is precisely this illusion of peace that makes the question of consent impossible to ignore. One could say, then, that war conducted by democracies should first of all be recognised as such, and only then should it demand a higher standard of justification and a fuller form of consent. The gap the people can (and should) accept elsewhere between what society wants and what their representatives do is, in this case, less tolerable as its costs are not measured in policies but in human lives.

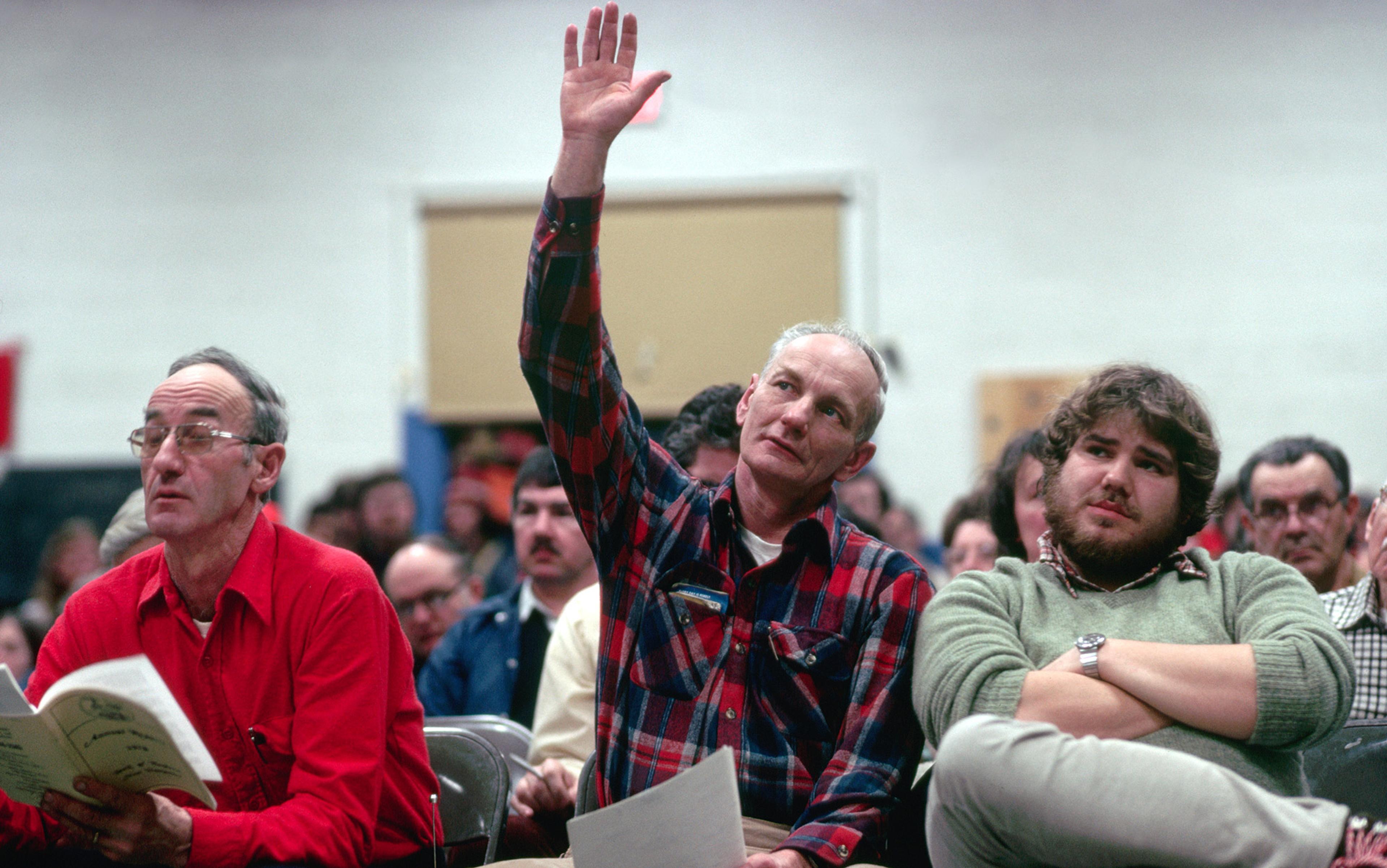

Watching the news each day, it seems to me that this longing for consent, this demand to be included, is not just a matter of institutional reform. It feels like something many citizens already sense, a shared intuition that democracy, when speaking of war, must evolve if it is to remain itself. For example, across societies that call themselves free, citizens are marching to protest their governments’ support for the conflict in Gaza. From London to Rome, from New York to Melbourne, from Dhaka to Kuala Lumpur, the message is the same: not in our name. Protests, of course, are not new. They have always been part of civic life. But this time, they feel different. They seem broader, more coordinated and remarkably persistent, spreading across continents and lasting far beyond a single news cycle. It suggests that something deeper is shifting in the political conscience of democratic societies.

The Gaza freedom flotillas, organised by ordinary civilians rather than states, made this conviction visible: their attempts to break the Gaza blockade to deliver humanitarian aid are an act of defiance against the idea that silence equals consent. Yet these reactions, powerful as they are, all come after the fact. They arise only once decisions have already been made. Protest, in fact, becomes the last language available when the institutional voices lapse into quiet obedience. Protest allows citizens to express refusal, but it also shows how little space remains for them within the formal decision-making process. Because protest occurs outside the architecture of representation, it cannot by itself restore consent. It can register disapproval but not alter the process that excludes it. Governments can acknowledge demonstrations, even tolerate them, and still claim that the absence of an institutional veto amounts to approval. In this way, dissent can paradoxically sustain the silence it seeks to break.

At this stage, the conclusion seems inescapable: our democratic structures may need to evolve. If war challenges the ordinary logic of political delegation, it also calls for a more responsive, participatory framework, one capable of meeting its exceptional stakes. A mature democracy, though grounded in representative mechanisms, should be able to develop effective oversight over the use of force. Sometimes I wonder whether change begins with ideas or with awareness. Perhaps, in the end, it begins with knowledge. If citizens are to share responsibility for the choices made in their name, knowledge – meaning information about it – must become a public right, not a privilege.

The point is not that citizens should govern alone, but that governments shouldn’t either

No one can deliberate about a war they do not even know is being fought. Every act of intervention abroad, every supply of weapons or alliance commitment, should come with an obligation to explain itself, to make its purpose, its risks, and its costs visible. Transparency, however, is only the beginning. Knowledge has to lead somewhere… to reflection, to judgment, to spaces where power pauses long enough for conscience to catch up. In some democracies, parliaments still vote before sending troops abroad. It is a sign of restraint, but too often it happens behind closed doors. Open-discussion assemblies could be created, spaces where citizens can speak – maybe not to decide but to question those who decide in their name. Their task would be not to command, but to interrupt the machinery of decision-making just long enough for a society – and, with it, democracy itself – to think. Beyond that, one could imagine going further, creating a moment when citizens themselves are asked to confirm or refuse participation in a conflict, especially when it is not in direct self-defence. Such a ‘war veto’ need not be an obstacle to action, but a space for collective judgment, where the democratic will reappears precisely when the stakes are highest.

These ideas are not utopian. Recent history reminds us that this is possible. After the 2008 banking crisis, Iceland offered a striking example. Instead of turning inward in anger or distrust, the country opened up. A group of randomly selected citizens was invited to discuss the principles of a new constitution. They were not politicians or experts, but ordinary people reflecting together on shared materials, with the help of independent facilitators. The goal was not to replace parliament, but to stand beside it, to ensure that reconstruction was not only economic, but democratic as well.

This was not an isolated case. Similar experiences in other democracies have shown that citizen involvement is not an obstacle to governability, but a form of collaboration. It does not overthrow representation; it completes it. Probably, it should be seen as way to bring political responsibility back into public conversation and give substance once again to the word ‘consent’. The point is not that citizens should govern alone, but that governments shouldn’t either. Popular sovereignty does not live only in the ballot box, but in the capacity to be called to reflection when history knocks at the door.

In the end, perhaps the true ‘silent mandate’ is not the one that citizens endure, but the one they must break: the duty to speak when silence has become convenient. Every democracy lives through moments when it must find its voice again, reclaim its own name. War is one of them. Defending democracy in times of war means refusing to let our name be used without our voice. And above all, it means asking whether the silence that shields us today might ultimately endanger the freedom we hope to preserve tomorrow.