Today, many people see democracy as under threat in a way that only a decade ago seemed unimaginable. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed like democracy was the way of the future. But nowadays, the state of democracy looks very different; we hear about ‘backsliding’ and ‘decay’ and other descriptions of a sort of creeping authoritarianism. Some long-established democracies, such as the United States, are witnessing a violation of governmental norms once thought secure, and this has culminated in the recent insurrection at the US Capitol. If democracy is a torch that shines for a time before then burning out – think of Classical Athens and Renaissance city republics – it all feels as if we might be heading toward a new period of darkness. What can we do to reverse this apparent trend and support democracy?

First, we must dispense with the idea that democracy is like a torch that gets passed from one leading society to another. The core feature of democracy – that those who rule can do so only with the consent of the people – wasn’t invented in one place at one time: it evolved independently in a great many human societies.

Over several millennia and across multiple continents, early democracy was an institution in which rulers governed jointly with councils and assemblies of the people. From the Huron (who called themselves the Wendats) and the Iroquois (who called themselves the Haudenosaunee) in the Northeastern Woodlands of North America, to the republics of Ancient India, to examples of city governance in ancient Mesopotamia, these councils and assemblies were common. Classical Greece provided particularly important instances of this democratic practice, and it’s true that the Greeks gave us a language for thinking about democracy, including the word demokratia itself. But they didn’t invent the practice. If we want to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of our modern democracies, then early democratic societies from around the world provide important lessons.

The core feature of early democracy was that the people had power, even if multiparty elections (today, often thought to be a definitive feature of democracy) didn’t happen. The people, or at least some significant fraction of them, exercised this power in many different ways. In some cases, a ruler was chosen by a council or assembly, and was limited to being first among equals. In other instances, a ruler inherited their position, but faced constraints to seek consent from the people before taking actions both large and small. The alternative to early democracy was autocracy, a system where one person ruled on their own via bureaucratic subordinates whom they had recruited and remunerated. The word ‘autocracy’ is a bit of a misnomer here in that no one in this position ever truly ruled on their own, but it does signify a different way of organising political power.

Early democratic governance is clearly apparent in some ancient societies in Mesopotamia as well as in India. It flourished in a number of places in the Americas before European conquest, such as among the Huron and the Iroquois in the Northeastern Woodlands and in the ‘Republic of Tlaxcala’ that abutted the Triple Alliance, more commonly known as the Aztec Empire. It was also common in precolonial Africa. In all of these societies there were several defining features that tended to reinforce early democracy: small scale, a need for rulers to depend on the people for knowledge, and finally the ability of members of society to exit to other locales if they were unhappy with a ruler. These three features were not always present in the same measure, but collectively they helped to underpin early democracy.

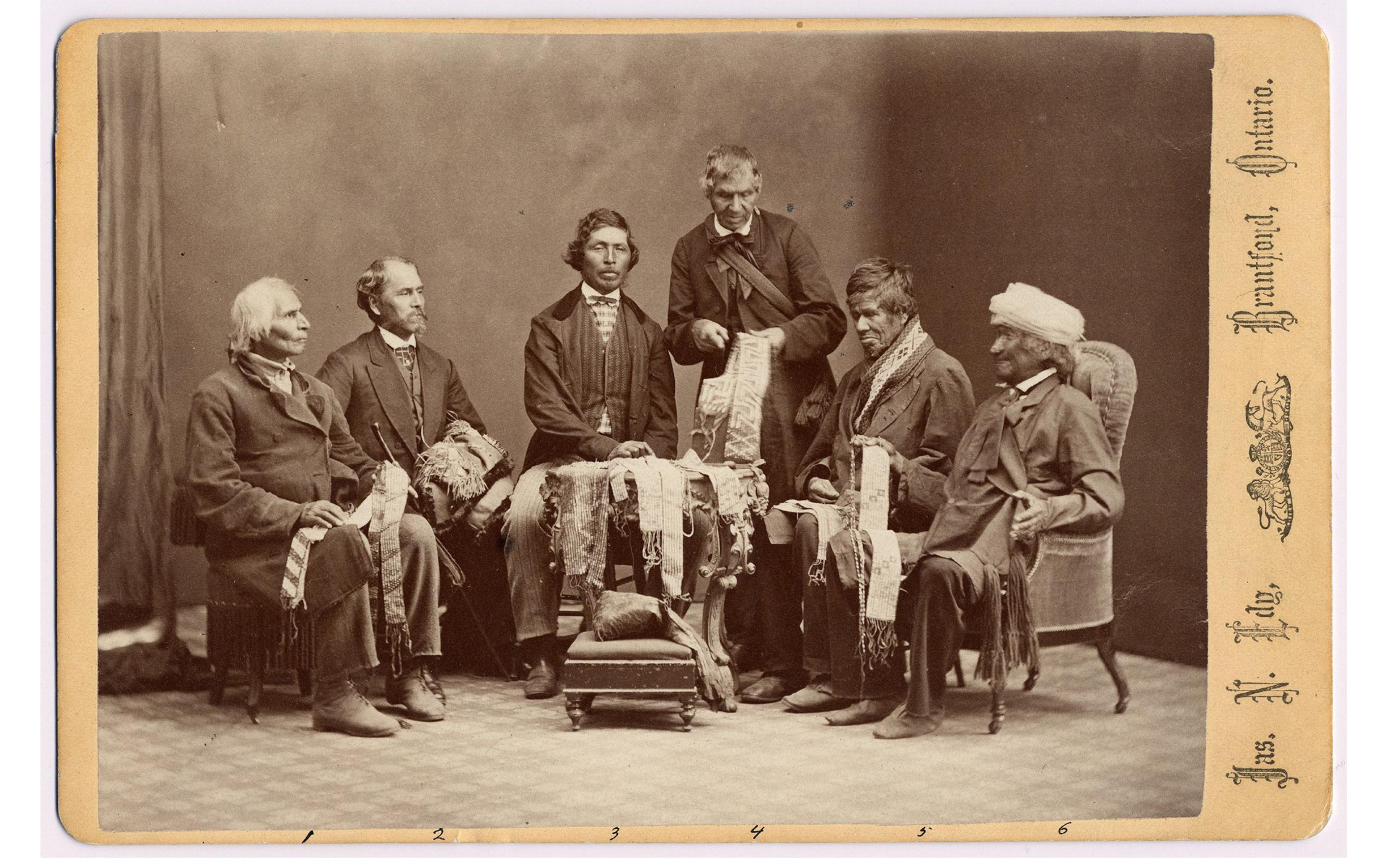

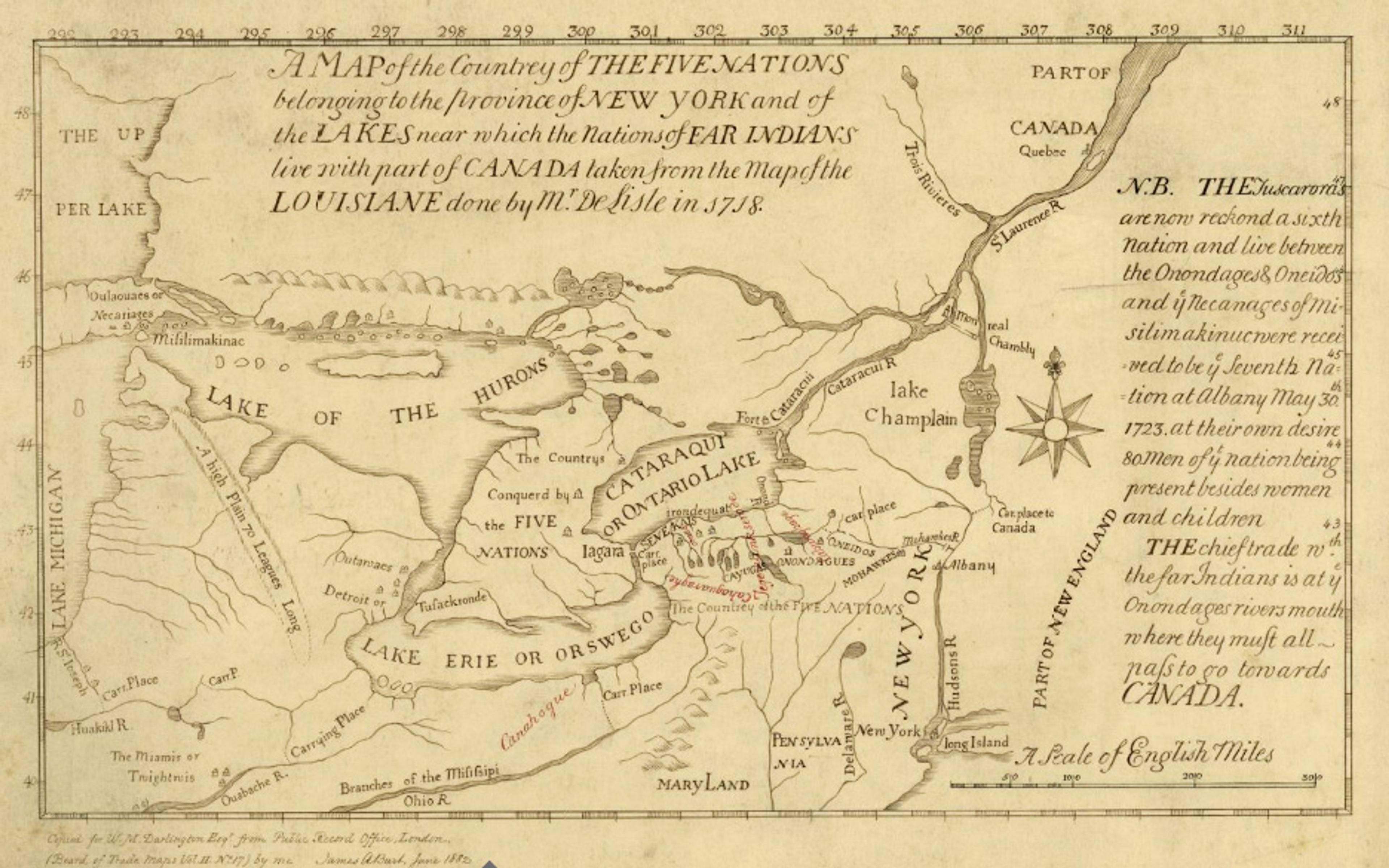

A map of the Iroquois Confederacy from 1730, copied by James Burt, London, in 1882. Courtesy the Darlington Collection, University of Pittsburgh

To see how autocracy – the alternative to early democracy – functioned, we can find no better example than that of Imperial China. China’s earliest historical dynasties, the Shang and the Zhou (from the 2nd and 1st millennia BCE), had kings who ruled through an army and a bureaucracy, and there is no evidence of councils or assemblies of the people. Autocracy has been a near-constant feature of rule in China, suggesting that it wasn’t some aberration but instead simply a different path of political development from Western European societies. The culmination of the Chinese model, achieved during the Tang and Song dynasties (7th to 13th centuries CE), involved the incorporation of the political elite into the state via a system of meritocratic recruitment based on a civil service exam. The Chinese civil service exam – which Europeans with their weak states later marvelled at – served a purpose not so different from a parliament but in a fundamentally different way because it was not local people who chose the representatives.

Of course, a simple return to early democracy is neither possible nor desirable. But early democracy does help us better understand the frailties of the modern democratic experience. A closer look at early democracy can in turn help us to understand what we might do to see that democracy today fulfils the underlying idea of demokratia: bringing power to the people.

The first difference between early democracy and our democracies today is that this earlier form of rule was a small-scale phenomenon. In some cases, governance took place only at the level of a small community, as was the case with the Hidatsa, an Indigenous American group living on the banks of the upper Missouri River. When governance was local like this, councils tended to meet very frequently. In other instances, such as with the Mesopotamian Kingdom of Mari, a larger polity existed, but early democracy remained a local phenomenon practised through the assemblies of individual towns. These might meet to consider how taxes should be allotted. It was rarer to see an early democracy that had a larger-scale assembly that drew members from multiple locations as did the Huron confederacy. Even in that case, though the Huron moved over a large area, the territory of concentrated settlement remained compact, something like 56 km east to west, and 30 km north to south. Populations were similarly small compared with modern democracies, with the Huron confederacy composed of, roughly, only 20,000 individuals.

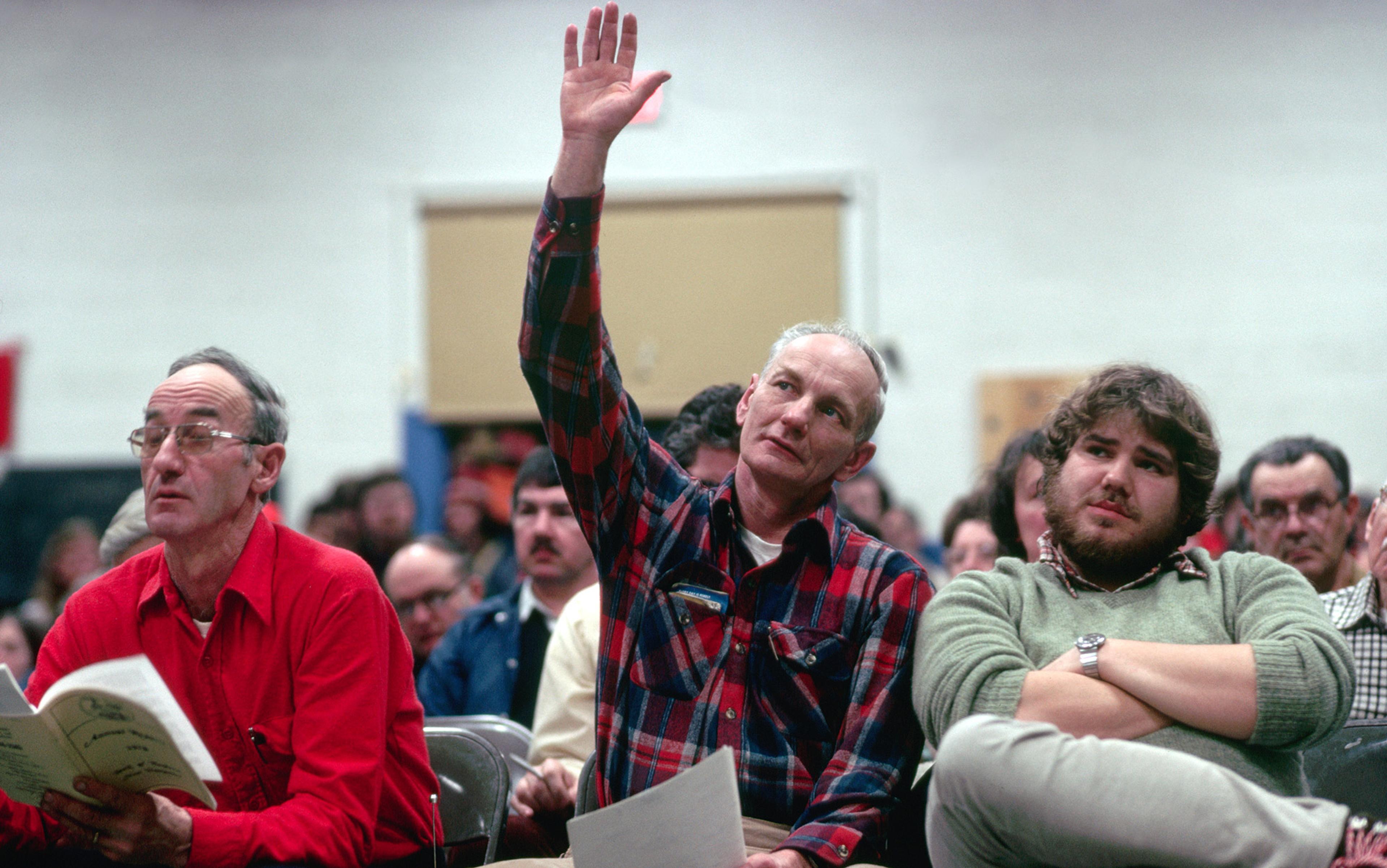

Small scale had a critical implication for the nature of politics; in Classical Athens, among the Hidatsa and in the Kingdom of Mari, those who had the right to participate in politics tended to do so in a very direct and intensive way, particularly in local assemblies. In modern democracy, participation is very broad – often broader than in early democracy – but it’s also not deep; for most of us, it’s limited to voting in elections every few years, and in between these moments others make the decisions. The potential risk of this arrangement, as has been noted by astute observers since the birth of modern republics, is that citizens might grow distrustful of the people who are actually running government on a daily basis and of the special influences to which they might be subject. It’s worth noting that, among long-established democracies today, there’s a robust correlation whereby countries with larger populations tend to have lower trust in government.

We need new investments that better connect citizens with government

One way to address the problem of scale is to delegate much more power to states, provinces and localities. There are some today, such as the American political analyst Yuval Levin, who here invoke the principle of subsidiarity: devolve power to the lowest level that’s practical. In some Western democracies, such as Canada, Germany or the US, the presence of a federal system ensures that this is already the case for many policies, but this strategy can go only so far. On crucial issues of foreign trade, diplomacy or pressing constitutional questions, for example, it’s impractical for individual states, regions or provinces to set their own policy.

If we can’t return to ‘all politics is local’, then one alternative is to see what could be done to better connect citizens with a distant state. Historically, one way this has happened is through investments in the diffusion of information.

The early republic in the US provides an important example of government investment to overcome the problem of scale. In ‘Federalist Number 10’ (1787), James Madison had written that a large republic would naturally suffer less turbulence than would a small one, but a few years after the ratification of the Constitution, he began to sing a very different tune. In an essay entitled ‘Public Opinion’, Madison wrote about the difficulty in a vast republic that people would have in informing themselves about government. So he advocated the subsidised distribution of newspapers, and this helped result in the passage of the Postal Service Act of 1792.

The world today is much different than it was in 1792; citizens, if they want to, can drown themselves in information and disinformation. This suggests that we need to think of new investments that might better connect citizens with government by giving them information sources that are in touch with reality and that, in the case of the US, would avoid fanning the flames of longstanding racism. In some countries, most notably the US and the United Kingdom, the local press, though known to be both more trusted and less partisan than national outlets, faces economic conditions that are leading to its disappearance. A subsidy for local news outlets could be money well spent, just as the subsidy that the US Congress voted in 1792 was appropriate.

If large scale has the potential to lead to distrust and disengagement in a democracy, then a closely related problem is that of polarisation. Polarisation can take many forms, such as that involving tensions between different classes of people in the same location, or a difference of opinions between people living in different locations. In a broad set of democracies today, polarisation has increasingly taken this latter form, with those in large, cosmopolitan urban centres acquiring an entirely different worldview from those elsewhere, whether they involve rural districts as in the US, or distant urban centres in the UK, or the contrast between more urban and western areas in Turkey and those areas further to the east. In many of these cases, political scientists have shown that polarisation is asymmetric, as those on the political Right have been the principal ones to move to the extremes. The problem of geographic polarisation was not unknown to people in early democracies, and they found creative ways of addressing it. While we can’t simply copy the solutions they found, we can still certainly learn from them.

Consider the example of the reforms implemented by Cleisthenes in Athens beginning in the year 508 BCE. In the decades prior to this date, the Athenians had developed a collective form of governance with a Council of Four Hundred, which had been established by Solon earlier in the 6th century BCE. It was composed of 100 members from each of four historical tribes, which might have been primarily kin-based or occupation-based, depending on which source one considers. While this system provided equal representation for each tribe, to the extent that there was animosity between these groups – one might even say polarisation – the system of representation might have reinforced this tension. Seeking to change matters, upon assuming power in 508 BCE, Cleisthenes revamped Athenian society by doing away with the four traditional tribes and creating 10 new ones to replace them. Aristotle later recounted a crucial element of Cleisthenes’ reform: he assigned individual local groups of people called demes by lot into each of the 10 new tribes, therefore ‘intermixing the members’ of the prior four tribes. Aristotle states further that Cleisthenes made sure that the new tribes weren’t geographically concentrated; instead, each had deme membership from the city, the coast and the interior of the Attic Peninsula.

People in polarised societies today could learn something from the Iroquois clan system

Importantly, the principle of Cleisthenes’ reform is far from unique; we have eloquent examples of people in other early democracies across multiple continents doing more or less the same thing. To see this, we can return to examples of the Huron and the Iroquois societies, each of which was divided – much like the Athenians – into separate tribes, and clearly geographically demarcated. This might seem like a system that would be ripe for intertribal conflict. But the Huron and the Iroquois had an ingenious system to fight against localism and polarisation. They divided their society not only into tribes, composed of villages, but also into clans that cross-cut tribal divisions. So, if you were a member of the wolf clan in an individual village among the Cayuga tribe in the Iroquois confederacy, to take one example, then you had a natural affiliation with Cayuga members of that clan from other villages, and you also had a link to members of the wolf clan in other Iroquois tribes. The clear intent of this system was to better bind society together by mitigating polarisation along tribal lines.

People in polarised societies today could learn something from the Iroquois clan system and the 10 Athenian tribes. As we become ever more tribal in nature in countries such as the US, perhaps we could learn more from societies that actually had tribes. The lesson wouldn’t be to establish new tribes or clans of our own: it would be, instead, to examine how different political and social institutions can aid in creating links for people living in different places, from different backgrounds and holding very different beliefs. The idea here would be to help strengthen and unify society by creating new links across the lines of polarisation.

The absence of a state bureaucracy was a chief reason why early democracy proved to be such a stable form of rule for so many societies. With little autonomous power – apart from the ability to persuade – those who would have liked to rule as autocrats found themselves without the means to do so. The flipside of this was that, in many early democracies, those who were unhappy with a central decision could simply refuse to participate or even decamp to a new locality. It was much like many online communities today where those at the centre, sometimes called ‘benevolent dictators for life’, have no option to rule as autocrats because they depend upon input and services provided by individuals who could simply refuse to participate or move elsewhere.

Modern democracy lacks the same protections from central power that early democracies enjoyed. At the same time, having a powerful central state can allow a society to achieve goals such as universal education and prosperity, to name but a few. The question then is how to live with a state while preserving democracy. Doing so involves remaining vigilant about the encroachment of central state power rather than hoping that a country’s constitution alone might provide adequate protection, most notably in the case of the US where the document was laid out at a now-distant founding moment.

Those who debated the US Constitution of 1787 recognised the danger posed by an encroaching central state. The compromise they achieved resulted in an extensive series of checks and balances designed to enable state power while also restraining it. The administration of the former US president Donald Trump demonstrated just how much executive power could run rampant in spite of all the intended safeguards. In some eastern European countries, a similar pattern has taken place and even gone much further. In the 1990s, it was believed that the checks and balances safeguarding democracy would involve membership in the European Union and adhesion to its extensive set of supranational rules, yet in this decade the Fidesz party in Hungary and their Law and Justice counterparts in Poland have demonstrated that it’s possible to break a great many democratic norms – and in fact rewrite the formal rules – without having EU membership serve as an effective backstop. The lesson from all of these cases would seem to be that, while designing a constitution well is an important thing, after that point maintaining a healthy democracy in the face of executive power requires constant vigilance, and perhaps more vigilance than we had been used to paying until late.

Recent decades have seen a substantial expansion of presidential power that poses a risk to US democracy

The most extreme way to constrain executive power – again by returning to early democracy – would be to drastically limit it by allowing for neither a standing army nor a tax bureaucracy. We can think here of the US senator Ted Cruz, who as a presidential candidate in 2015 proposed abolishing the Internal Revenue Service. With the example of how Prussian despotism took hold after the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) very much in mind, 18th-century thinkers saw a standing army in particular as something that invited tyranny. But in the places where people expressed the deepest worries about this possibility – the UK and its settler colonies – the eventual rise in power of the central state to extract resources and to use coercive force didn’t result in the demise of democracy. The reason for this is that, when there is a deep tradition of consultative rule established first, it’s possible for an executive and representatives of the people to build and control a state together. The key question is one of sequencing: does a strong state emerge prior to some form of collective rule or is it the reverse?

When collective governance precedes state construction, this can help secure democracy, but this sequence alone doesn’t ensure it. It’s ultimately up to individual legislators – as well as the people who elect them – to oppose attempts by executives to accrue ever more power. In a country like Hungary, which lacks a long tradition of democratic rule, it might not seem so surprising that this mechanism has failed but, in a country like the US, it’s been far more surprising to see the illiberal actions taken by the Trump administration, most often as a result of executive order.

In the case of the US, there’s an argument to be made that the reason why the Trump administration was able to go so far is that recent decades have seen a substantial, creeping expansion of presidential power that, in the end, poses a risk to our democracy. In a book published a decade ago, Bruce Ackerman, a prominent legal scholar, wrote that this trend – something that occurred under both Democratic and Republican administrations – carried the risk that the White House could become a ‘platform for charismatic extremism and bureaucratic lawlessness’. We should be more vigilant about warnings such as this.

The lessons are clear: we will be best positioned to preserve our own democracies if we recognise that the history of democracy is much broader and deeper than is often presumed. People around the world, throughout history, have devised democratic institutions and practised democracy. We can learn from their experience to see how democracy today might be strengthened.