Over the past century, a powerful idea has taken root in the educational landscape. The notion of intelligence as something innate and fixed has been supplanted by the idea that intelligence is instead something malleable; that we are not prisoners of immutable characteristics and that, with the right training, we can be the authors of our own cognitive capabilities.

Nineteenth-century scientists including Francis Galton and Alfred Binet devoted their own considerable intelligence to a quest to classify and understand human cognitive ability. If we could codify the anatomy of intelligence, they believed, we could place individuals into their correct niche in society. Binet would go on to develop the first IQ tests, laying the foundations for a method of ranking the intelligence of job applicants, army recruits or schoolchildren that continues today.

In the early 20th century, progressive thinkers revolted against this idea that inherent ability is destiny. Instead, educators such as John Dewey argued that every child’s intelligence could be developed, given the right environment. The self, according to Dewey, is not something ‘ready made’ but rather ‘in continuous formation through choice of action’. In the 1960s and ’70s, psychologists such as Albert Bandura bridged some of the gap between the innate and the learned models of intelligence with his idea of social cognitive theory, self-efficacy and motivation. One can recognise that there are individual differences in ability, Bandura argued, but still emphasise the potential for growth for each individual, wherever one’s starting point.

Growth mindset theory is a relatively new – and wildly popular – iteration of this belief in the malleability of intelligence, but with a twist. In many schools today you will see hallways festooned with motivational posters, and hear speeches on the mindset of great sporting heroes who simply believed their way to the top. These are all attempts to put growth mindset theory into practice through motivation. However a growth mindset is not really about motivation, but rather about the way in which individuals understand their own intelligence.

According to the theory, if students believe that their ability is fixed, they will not want to do anything to reveal that, so a major focus of the growth mindset in schools is shifting students away from seeing failure as an indication of their ability, to seeing failure as a chance to improve that ability. As Jeff Howard noted almost 30 years ago: ‘Smart is not something that you just are, smart is something that you can get.’

Despite extraordinary claims for the efficacy of a growth mindset, however, it’s increasingly unclear whether attempts to change students’ mindsets about their abilities have any positive effect on their learning at all. And the story of the growth mindset is a cautionary tale about what happens when psychological theories are translated into the reality of the classroom, no matter how well-intentioned.

The idea of the growth mindset is based on the work of the psychologist Carol Dweck at Stanford University in California. Dweck’s findings suggest that beliefs about ourselves can have a profound effect on academic achievement and beyond. Her seminal work stems from a paper 20 years ago that reported on a research project with schoolchildren that probed the relationship between their understanding of their own abilities and their actual performance.

In the experiment, a group of 10- to 12-year-olds were divided into two groups. All were told that they had achieved a high score on a test but members of the first group were praised for their intelligence in achieving this, while the others were praised for their effort. The second group were subsequently far more likely to put effort into future tasks while the former took on only those tasks that would not risk their initial sense of worth. Praising ability actually made the students perform worse, while praising effort emphasised that change was possible.

Dweck’s work suggests that when people believe that failure is not a barometer of innate characteristics but rather view it as a step to success (a growth mindset), they are far more likely to put in the kinds of effort that will eventually lead to that success. By contrast, those who believe that success or failure is due to innate ability (a fixed mindset) can find that this leads to a fear of failure and a lack of effort.

Imagine two children who are faced with taking a test on a tricky maths problem. The first child completes the first few steps but then hits a wall, and instantly feels demotivated. For this child, the small failure is incontrovertible evidence of simply not being good at maths. By contrast, for the second child, this small failure is merely a barrier to eventual success, and confers an opportunity to improve overall maths ability. The second child relishes the challenge, and works to improve – that child is displaying a growth mindset. According to the theory, the key to encouraging this disposition is to praise the effort and not the ability. By telling children that they are smart or intelligent, you are merely confirming the idea of innate ability, fostering a fixed mindset, and actually undermining their development. Dweck’s claims are supported by a lot of evidence, indeed she and her associates have spent more than 30 years exploring this phenomenon, including taking the time to respond to criticism in an open and transparent way.

Growth mindset theory has had a profound impact on the ground. It is difficult to think of a school today that is not in thrall to the idea that beliefs about one’s ability affect subsequent performance, and that it’s crucial to teach students that failure is merely a stepping stone to success. Implementing these ideas has been much harder, however, and attempts to replicate the original findings have not been smooth, to say the least. A recent national survey in the United States showed that 98 per cent of teachers feel that growth mindset approaches should be adopted in schools, but only 50 per cent said that they knew of strategies to effectively change a pupil’s mindset.

The truth is we simply haven’t been able to translate the research on the benefits of a growth mindset into any sort of effective, consistent practice that makes an appreciable difference in student academic attainment. In many cases, growth mindset theory has been misrepresented and miscast as simply a means of motivating the unmotivated through pithy slogans and posters. A general truth about education is that the more vague and platitudinous the statement, the less practical use it has on the ground. ‘Making a difference’ rarely makes any difference at all.

A growing number of recent studies are casting doubt on the efficacy of mindset interventions at scale. A large-scale study of 36 schools in the UK, in which either pupils or teachers were given training, found that the impact on pupils directly receiving the intervention did not have statistical significance, and that the pupils whose teachers were trained made no gains at all. Another study featuring a large sample of university applicants in the Czech Republic used a scholastic aptitude test to explore the relationship between mindset and achievement. They found a slightly negative correlation, with researchers claiming that ‘the results show that the strength of the association between academic achievement and mindset might be weaker than previously thought’. A 2012 review for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in the UK of attitudes to education and participation found ‘no clear evidence of association or sequence between pupils’ attitudes in general and educational outcomes, although there were several studies attempting to provide explanations for the link (if it exists)’. In 2018, two meta-analyses in the US found that claims for the growth mindset might have been overstated, and that there was ‘little to no effect of mindset interventions on academic achievement for typical students’.

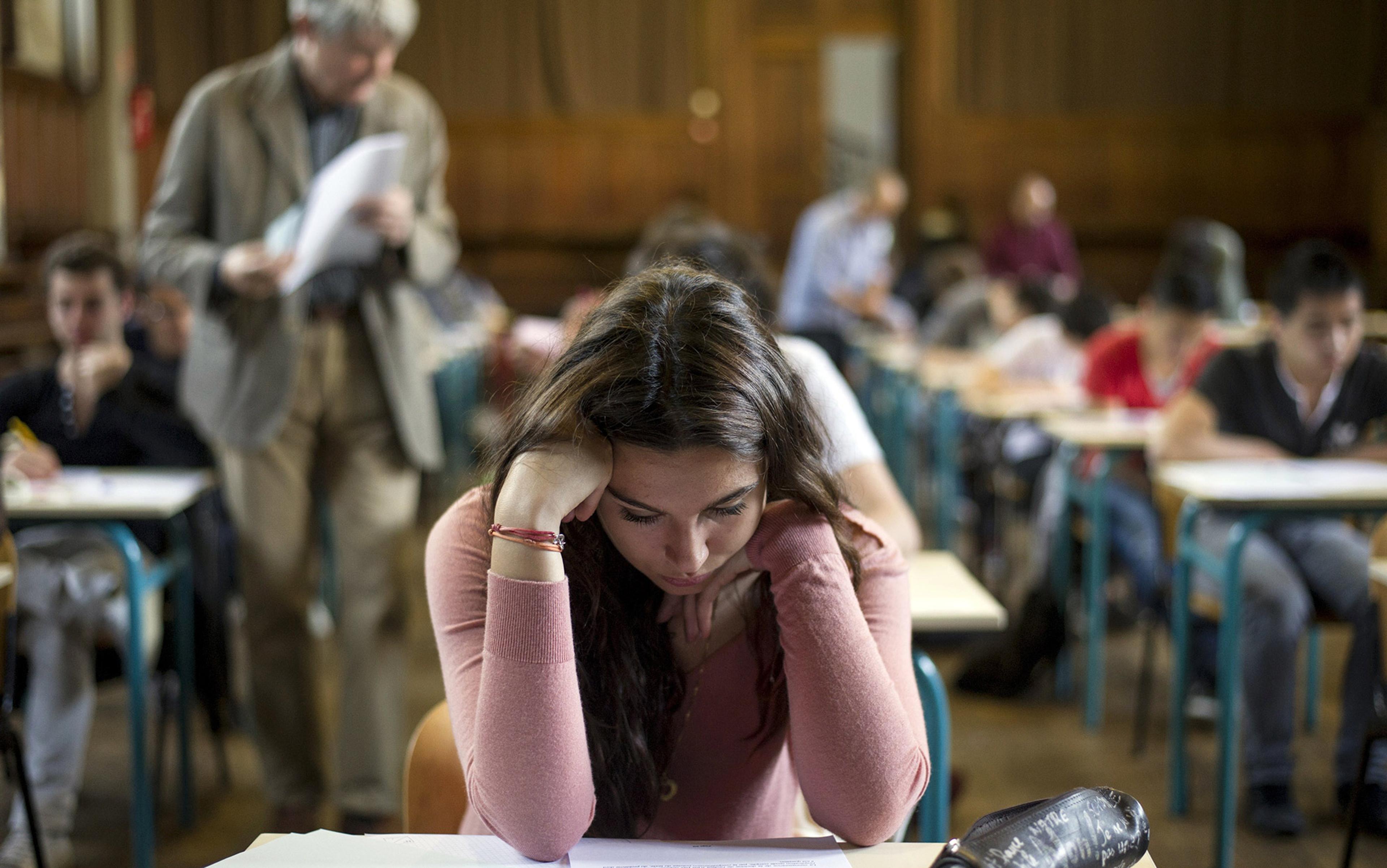

‘Kids with the growth mindset aren’t getting better grades’

One of the greatest impediments to successfully implementing a growth mindset is the education system itself. A key characteristic of a fixed mindset is a focus on performance and an avoidance of any situation where testing might lead to a confirmation of fixed beliefs about ability. Yet we are currently in a school climate obsessed with performance in the form of constant summative testing, analysing and ranking of students. Schools create a certain cognitive dissonance when they proselytise the benefits of a growth mindset in assemblies but then hand out fixed target grades in lessons based on performance.

Aside from the implementation problem, the original growth mindset research has also received harsh criticism and been difficult to replicate robustly. The statistician Andrew Gelman at Columbia University in New York claims that ‘their research designs have enough degrees of freedom that they could take their data to support just about any theory at all’. Timothy Bates, a professor of psychology at the University of Edinburgh who has been trying to replicate Dweck’s work in a third study in China, is finding that the results are repeatedly null. He notes in a 2017 interview that: ‘People with a growth mindset don’t cope any better with failure. If we give them the mindset intervention, it doesn’t make them behave better. Kids with the growth mindset aren’t getting better grades, either before or after our intervention study.’

An enduring criticism of growth mindset theory is that it underestimates the importance of innate ability, specifically intelligence. If one student is playing with a weaker hand, is it fair to tell the student that she is just not making enough effort? Growth mindset – like its educational-psychology cousin ‘grit’ – can have the unintended consequence of making students feel responsible for things that are not under their control: that their lack of success is a failure of moral character. This goes well beyond questions of innate ability to the effects of marginalisation, poverty and other socioeconomic disadvantage. For the US psychiatrist Scott Alexander, if a fixed mindset accounts for underachievement, then ‘poor kids seem to be putting in a heck of a lot less effort in a surprisingly linear way’. He sees growth mindset as a ‘noble lie’, and notes that saying to kids that a growth mindset accounts for success is not exactly denying reality so much as ‘selectively emphasising certain parts of’ it.

Much of this criticism is not lost on Dweck, and she deserves great credit for responding to it and adapting her work accordingly. In a recent blog, she noted that growth mindset theory ‘is on a firm foundation, but we’re still building the house’. In fact, she argues that her work has been misunderstood and misapplied in a range of ways. She has also expressed concerns that her theories are being misappropriated in schools by being conflated with the self-esteem movement: ‘The thing that keeps me up at night is that some educators are turning mindset into the new self-esteem, which is to make kids feel good about any effort they put in, whether they learn or not. But for me the growth mindset is a tool for learning and improvement. It’s not just a vehicle for making children feel good.’

For Dweck, it’s not just about more effort, but rather purposeful and meaningful effort. And it’s not just in the classroom where she feels that the growth mindset is being misunderstood, it seems to be happening in the home too: ‘We’re finding that many parents endorse a growth mindset, but they still respond to their children’s errors, setbacks or failures as though they’re damaging and harmful,’ she said in an interview in 2015. ‘If they show anxiety or overconcern, those kids are going toward a more fixed mindset.’

Dweck might be right that the theory is not always well understood or put into practice. There is always the danger of disappointment in the translation from educational laboratory to classroom, and this is partly due to the Chinese whispers effect, whereby research becomes diluted and distorted as it goes through its journey. But there is another factor at work here. The failure to translate the growth mindset into the classroom might reflect a profound misunderstanding of the elusive nature of teaching and learning itself.

Effective teaching, at its best, defies prescription. The same resources and the same approaches that are successful in one classroom can be completely ineffective in another. In his book Personal Knowledge (1958), Michael Polanyi defined ‘tacit knowledge’ as anything we know how to do but cannot explicitly explain how we do it, such as the complex set of skills needed to ride a bike or the instinctive ability to stay afloat in water. It is the ephemeral, elusive form of knowledge that resists classification or codification, and that can be gleaned only through immersion in the experience itself. In most cases, it’s not even something that can be expressed through language. As Polanyi put it so beautifully in his book The Tacit Dimension (1966), ‘we can know more than we can tell’. As a contrarian colleague once said to me about his frustration with the increasing codification of the classroom: ‘Perhaps we should be brave enough to allow it to remain a mystery.’

Good teachers are like good actors, not in the sense that they are both artists, but in the sense that the best teachers teach you without you realising that you’ve been taught. If students get a whiff of being part of an ‘intervention’, then it is likely that the very awareness of this will have a detrimental effect. The growth mindset advocates David Yeager and Gregory Walton at Stanford claim that these interventions should not be seen as ‘magic’ and should be delivered in a ‘stealthy’ way to maximise their effectiveness – miles away from the standard use of motivational stories, posters and explanations of brain plasticity. As they put it in 2011: ‘if adolescents perceive a teacher’s reinforcement of a psychological idea as conveying that they are seen as in need of help, teacher training or an extended workshop could undo the effects of the intervention, not increase its benefits.’ Pedagogy is not medicine, after all, and students do not want to be treated as patients to be cured.

How students learn well can be very counterintuitive. You might think it is safe to assume that, once you motivate students, the learning will follow. Yet research shows that this is often not the case: motivation doesn’t always lead to achievement, but achievement often leads to motivation. If you try to ‘motivate’ students into public speaking, they might feel motivated but can lack the specific knowledge needed to translate that into action. However, through careful instruction and encouragement, students can learn how to craft an argument, shape their ideas and develop them into solid form.

The idea that videos of failed sportsmen can translate into a growth disposition is unrealistic

A lot of what drives students is their innate beliefs and how they perceive themselves. There is a strong correlation between self-perception and achievement, but there is some evidence to suggest that the actual effect of achievement on self-perception is stronger than the other way round. To stand up in a classroom and successfully deliver a good speech is a genuine achievement, and that is likely to be more powerfully motivating than woolly notions of ‘motivation’ itself.

One reason for this might be the over-generalised picture of the growth mindset: it tends to be talked about as a global or general skill as opposed to a domain-specific one. Many interventions focus on kids having a kind of global attitude to their own intelligence that can then be transferred to any learning situation but this is rarely the case. For example, some students can have a positive mindset in maths but a negative mindset in history due to a highly variable range of factors. The idea that a workshop on the plasticity of the brain and some videos of famous sportsmen who have failed in the past can translate into a domain-general growth disposition is simply unrealistic.

Students are most engaged when they are being supported through specific tasks to stretch their understanding beyond its current base, but ‘engagement’ doesn’t necessarily mean they’re learning anything. As the New Zealand education researcher Graham Nuthall showed in The Hidden Life of Learners (2007), ‘students can be busiest and most involved with material they already know. In most of the classrooms we have studied, each student already knows about 40-50 per cent of what the teacher is teaching.’ Nuthall’s work demonstrates that students are far more likely to get stuck into tasks they’re comfortable with and already know how to do, as opposed to the more uncomfortable enterprise of grappling with uncertainty and indeterminate tasks. The psychologists Elizabeth Ligon Bjork and Robert Bjork at the University of California, Los Angeles, describe such activities as ‘desirable difficulties’, which refers to the kinds of things that are difficult in the short term, but that lead to greater gains in the long term. These point to a range of strategies that are more prosaic and less attractive than growth mindset interventions – familiar strategies such as testing, self-quizzing and spacing out learning.

Clearly, something has gone wrong somewhere along the way between the laboratory and the classroom. The US education scholars Marilyn Cochran-Smith and Susan Lytle outline a fundamental problem with the education system. Teachers, they say in their book Inside/Outside (1992), are subject to top-down models of school improvement, and are often passive objects of study in the educational research that underpins those models:

The primary knowledge source for the improvement of practice is research on classroom phenomena that can be observed. This research has a perspective that is ‘outside-in’; in other words, it has been conducted almost exclusively by university-based researchers who are outside of the day-to-day practices of schooling.

In a very real sense, teachers have been given answers to questions they didn’t ask, and solutions to problems that never existed. It is not surprising that they feel subject to fads and theories about students that do not hold up to scrutiny. For example, the problem of how to plan lesson content to match the individual ‘learning style’ of students has now been proven to have been a waste of time, and a sad indictment of how much time and energy has been expended on theoretical interventions with little to no evidence to support them.

Recent evidence would suggest that growth mindset interventions are not the elixir of student learning that many of its proponents claim it to be. The growth mindset appears to be a viable construct in the lab, which, when administered in the classroom via targeted interventions, doesn’t seem to work at scale. It is hard to dispute that having a self-belief in their own capacity for change is a positive attribute for students. Paradoxically, however, that aspiration is not well served by direct interventions that try to instil it. Yet creating a culture in which students can believe in the possibility of improving their intelligence through their own purposeful effort is something few would disagree with. Perhaps growth mindset works best as a philosophy and not an intervention.

All of this indicates that using time and resources to improve students’ academic achievement directly might well be a better agent of psychological change than psychological interventions themselves. In their book Effective Teaching (2011), the UK education scholars Daniel Muijs and David Reynolds note: ‘At the end of the day, the research reviewed has shown that the effect of achievement on self-concept is stronger that the effect of self-concept on achievement.’

Many interventions in education have the causal arrow pointed the wrong way round. Motivational posters and talks are often a waste of time, and might well give students a deluded notion of what success actually means. Teaching students concrete skills such as how to write an effective introduction to an essay through close instruction, specific feedback, worked examples and careful scaffolding, and then praising their effort in getting there, is probably a far more effective way of improving confidence than giving an assembly about how unique they are, or indeed how capable they are of changing their own brains. The best way to achieve a growth mindset might just be not to mention the growth mindset at all.