In 1927, the American Communist leader Jay Lovestone aroused Moscow’s ire by arguing that industry in the United States was so youthful and vigorous as to be exempt from the traditional Marxist laws of capitalist crisis and decay. ‘American exceptionalism’ – the phrase that the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin used to describe Lovestone’s heresy – then went underground for more than half a century, only to emerge in the 1980s, strangely enough among US neoconservatives.

Standing Stalin on his head – or, as they would undoubtedly prefer, on his feet – the neocons argued that the US was exceptional after all, not just ‘the indispensable nation’, as the Secretary of State Madeleine Albright would later have it, but fundamentally different from every other country on Earth. Newt Gingrich wrote an entire book celebrating American exceptionalism while the Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney repeatedly invoked it on the 2012 campaign trail. ‘Our President doesn’t have the same feelings about American exceptionalism that we do,’ he complained. Not to be outdone, Barack Obama declared in a major foreign policy address last year: ‘I believe in American exceptionalism with every fibre of my being.’

As much as one might be tempted to write this off as typical American bluster, it happens to be correct – although not in ways the politicians realise. The US is exceptional. It’s exceptionally big, with two and a half times the population of any other member of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an organisation that includes most of the world’s richest countries. The US is also exceptionally wealthy, with a per-capita income at least 40 per cent above the OECD average. And it’s exceptionally powerful, with more than 700 military installations across the globe and a military budget greater than that of the next eight nations combined.

The US is exceptional in another way, too: constitutionally. Other countries have their parliaments and heads of state. But no other country invests such authority in a single document dating from the era of silk knee britches and powdered wigs. Sealed in moisture-controlled, bullet-proof glass containers that are on display in a special rotunda at the National Archives Museum in Washington DC by day and lowered into a multi-ton bomb-proof vault by night, the Constitution is to the US what the Bible was to medieval Europe or the Quran to today’s Islamic State, albeit with certain differences.

It’s much shorter: just 4,000 words in its original 1787 version. It’s also more rigorous and to the point: you don’t have to parse a story about Abraham or Moses to learn how the Congressional spending process works. All you have to do is turn to Article I, section 7, and learn that ‘all bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments as on other bills’ – which is more or less how things still work today.

On the other hand, unlike today’s Bible or the Quran, the Constitution is subject to textual emendation. This might seem to detract from its general aura of holiness, yet the fact that Americans must genuflect in the direction of the founding fathers every time they want to change so much as a comma actually works to enhance the sacredness of the whole.

In effect, the amending clause contained in Article V says that any change, no matter how minor, must be approved by two-thirds of each house of Congress plus three-fourths of the states. This is daunting, certainly. But growing population disparities render it even more so since the three-fourths rule means that 13 states representing as little as 4.4 per cent of the population can veto any change sought by the remaining 95.6 percent of the population.

As a result, Americans have succeeded in modifying the Constitution only 17 times since ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791. Since amendments tend to come in clumps during periods of exceptional turmoil, this means that decades can race by without any change at all. For instance, the US was constitutionally frozen for nearly 60 years prior to the Civil War, and then spent another 40 years in a constitutional deep-freeze during the Gilded Age that followed. Only one amendment, the 27th, concerning the scheduling of Congressional pay raises, has been approved since the civil-rights revolution of the 1960s and early ’70s, and that one was drafted in 1789 and then gathered dust in various state legislatures for more than two centuries. Excepting this unusual amendment, the present constitutional ice age could wind up outlasting the first.

Arguably, this Constitutional paralysis is the real source of American exceptionalism – not America’s military or economic clout, but its basic political structure, so unlike that of just about any other country on Earth. It’s certainly the source of its exceptional political psychology. One might think that Americans would be impatient with a Constitution that frustrates any and all efforts at reform, yet the response has been the opposite: instead of growing angry, people have reassured themselves over the years that immobility is all to the good because anything they do to change things can only make them worse. In effect, they’ve taken the old adage, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,’ and turned it around. Since a fix is impossible due to the system’s deep-seated resistance to change, then it must not be broken at all. In fact, it must be perfect and therefore divinely inspired. And if the Constitution is divinely inspired, can the US be anything other than divinely inspired as well?

Who rules, the people or a piece of parchment?

The Constitution is perfect because it’s impervious to change and vice versa. This is exceptional all right, as well as more than a bit odd. After all, cars, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners all run down from time to time, so why not the US machinery of government? Why should it be spared the usual wear and tear? This would seem to be the case especially given the news out of Washington these days about gridlock, high-wire negotiations, and government shutdowns. Surely, a government that periodically shuts its doors due to budget disputes between the executive and legislative branch can’t be said to be functioning up to snuff? In fact, it seems more and more dysfunctional. Yet everyone say it’s the greatest system on Earth. How can that be?

The perception gap extends beyond the machinery of government. Foreigners, for example, are perplexed by US gun laws. How can a modern society insist on every citizen’s right to own assault rifles and other high-powered weaponry that in just about every other country are banned? When informed that a majority of Americans have historically favoured effective gun control but that the federal courts, citing the Second Amendment, have increasingly ruled them out of order, their confusion deepens. How can Americans be required to live under the Second Amendment if they don’t want to? Who rules, the people or a piece of parchment? On one hand, the Preamble seems to establish ‘we the people’ as the all-powerful makers and breakers of constitutions. On the other, the rest of the document outlines a system that gives them almost no power at all. So which is it?

Given all this, perhaps we can begin to understand what politicians mean when they utter the sacred phrase ‘American exceptionalism’. Like Lovestone back in the 1920s, today’s conservatives seem to be saying that logic is for little countries and not a hyperpower such as the US. Other countries might worry about a constitution that says one thing and then another, but not the US. It is above such rules. American exceptionalism, in their view, means not just that the US is exceptionally brave, generous and godly, but that it is ‘immune from the social ills and decadence that have beset all other republics in the past’, as the sociologist Daniel Bell once put it.

Where other countries’ fortunes rise and fall, the US therefore knows one direction only: onward and ever upward. Where lesser nations must tinker with the machinery of government to make it run more smoothly, Americans know that their system is so flawless that it doesn’t require tinkering at all. All they have had to do is sit back and watch as the perpetual-motion machine goes about its business. It’s a marvellous notion, but reality it is not. More than a century ago, the poet James Russell Lowell warned Americans that the Constitution was not ‘a machine that would go of itself’.

No country is very happy these days after half a dozen years of recession, but the US is in a class by itself. To be sure, the economy has held up better than most due to the Obama administration’s Keynesian stimulus policies and the advantages of issuing the global reserve currency. But while fuelling a boom on Wall Street, super-low interest rates have done little more than mask the pain for the great majority. Between 1989 and 2013, the share of wealth of the bottom nine-tenths fell from 33.2 to 24.7 per cent, while median household income has fallen better than 12 per cent since the start of the crisis in 2007.

Foreign policy is a disaster, especially in the Middle East where the US finds itself further drawn into an ever more ambiguous war. Conditions on Capitol Hill, after two decades of vicious partisan infighting, seem as polarised as ever. In other countries, partisanship is the stuff of modern politics. The ability to seek out like-minded individuals, formulate a programme, and then fight for its approval is what propels democracy forward. Yet in the US, the only effect is to overload the machinery and cause it to crash. The system is so larded with checks and balances favouring tiny minorities that it takes very little for a well-entrenched interest group to pull the emergency brake and bring the whole affair to a screeching halt.

As a consequence, breakdown has become the norm. While both sides claim to believe in bipartisanship, a Republican Party pushed around by its own Right-wing fringe has become so adept at obstructionism that normal legislative processes have given way to a kind of slow-motion trench warfare. The parties accuse one another of failing to co‑operate, and immobilisation is the norm.

If this isn’t a broken system, what is? Since economic polarisation is a global phenomenon, a sclerotic 18th century Constitution can’t be entirely to blame. But an increasingly unrepresentative system obviously doesn’t help. Thanks to a Senate that gives equal representation to all 50 states even though the largest (California) is now some 65 times more populous than the smallest (Wyoming), US government is arguably more undemocratic now than it was even in the 19th century.

the US claims to have written the book on democracy, but ‘we the people’ never had an opportunity to vote on the complicated checks and balances created in their name

In the 114th US Congress, 67.8 million people voted for senators who caucus with the Democratic Party, while 47.1 million voted for senators who caucus with the Republican Party. Yet those 67.8 million votes elected 46 senators while the 47.1 million votes elected 54 senators. Call this what you will, but representative it’s not. Thanks to a bizarre filibuster system that allows 41 senators (representing as little as 11 per cent of the population) to prevent any bill from reaching the floor, it has never been more unfair. Yet a fix is impossible. The results in the economic realm are all too obvious. While other countries have succeeded to a degree in bucking the trend toward financial oligopoly, the US has given it free reign. The system continues tottering forward because no one is able to come up with a viable alternative.

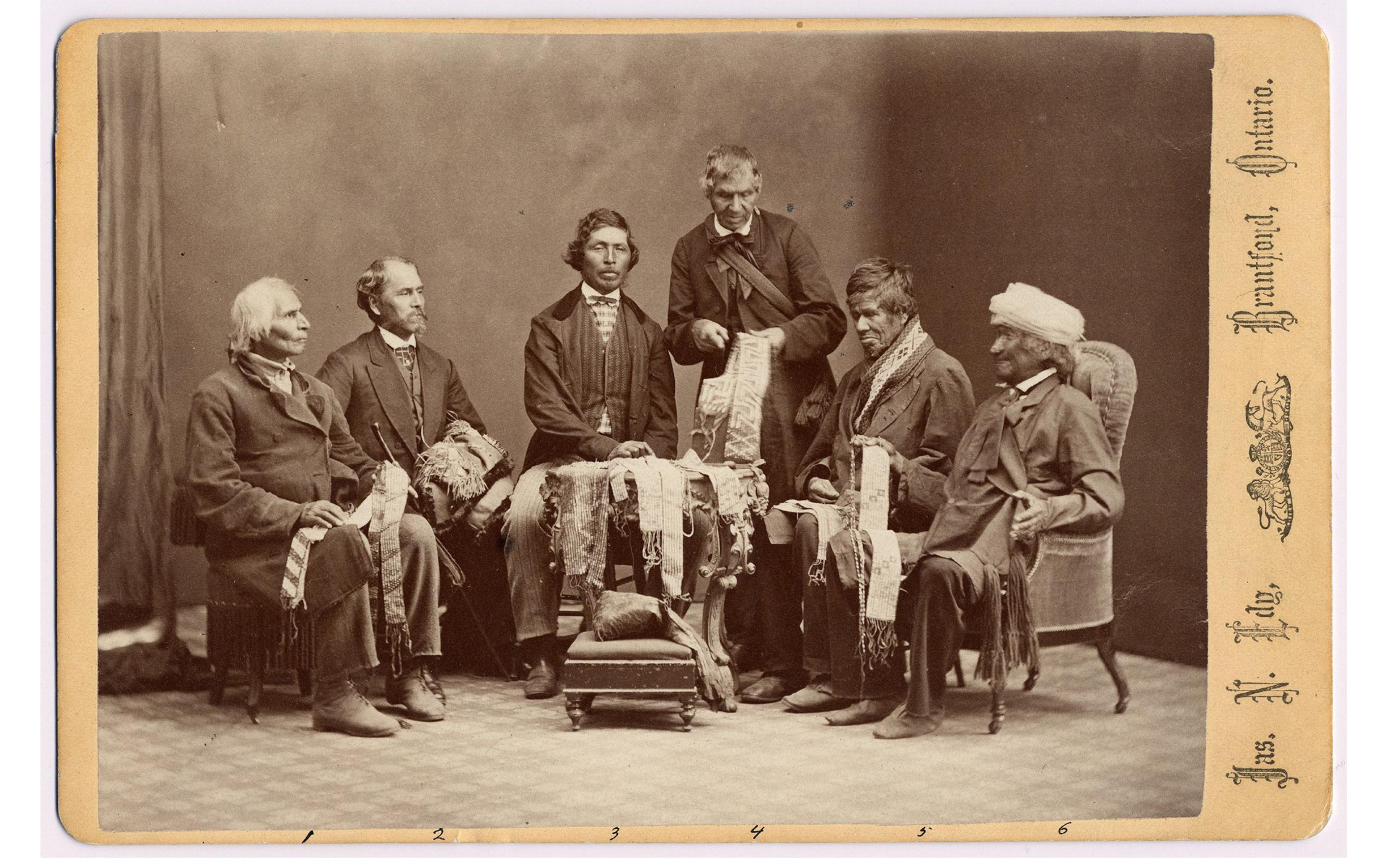

The US is thus a strange combination of might and weakness; a country able to project military firepower to the far corners of the globe yet incapable of addressing its own basic structural weaknesses. It insists that its 18th century governing system is flawless and loudly thumps its chest at anyone who dares say otherwise. Yet anyone who has bothered to look into the matter knows that it just isn’t so. Although the US claims to have written the book on democracy, the fact is that ‘we the people’ have never had an opportunity to vote on the complicated checks and balances created in their name. To be sure, Americans elected delegates to special state ratification conventions that eventually gave the document their assent. But as the historian Forrest McDonald pointed out half a century ago, women, blacks, native Americans, and non-property owners were all barred from voting while three-fourths of those eligible did not even bother to take part. This hardly qualifies as a ringing democratic endorsement.

Rather than a sign of strength, endless hosannas to American exceptionalism amount to so much whistling past the graveyard. Romney might tell the world that he ‘reject[s] the view that America must decline’ and proclaim his faith in American exceptionalism instead. But what can he do exactly to make the process stop? When the US columnist Ramesh Ponnuru says that decadent Europeans ‘are just waiting for someone to turn out the last light in the last gallery of the Louvre’ whereas ‘Americans are not prepared to go gentle into that good night’, he misses the point. What makes Dylan Thomas’ lines so poignant is that, no matter how much one rages against the dying of the light, it will flicker out regardless. If the phrase ‘American exceptionalism’ seems to be popping up more and more frequently, it is because many in the US are in denial about something that is by now glaringly apparent.

Nothing could be sillier than the notion of strolling into the 21st century with a pre-modern plan of government. It’s like sending an 18th century man-of-war into battle against a guided-missile destroyer. The US political system’s age, in other words, is showing.