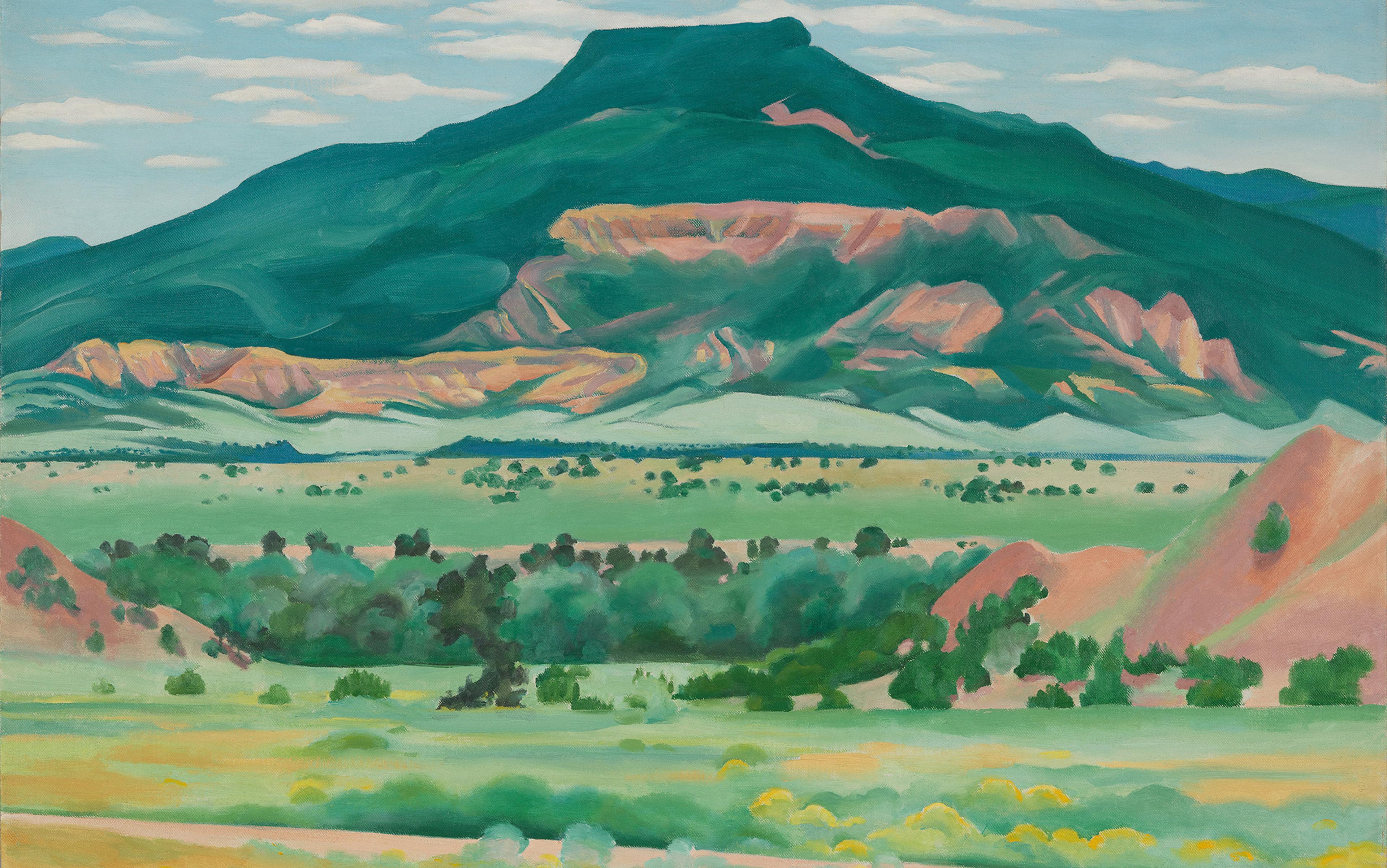

Interviewed in a 1977 documentary about her life and work as a painter, Georgia O’Keeffe, then 90, spoke of her hunger for the desert. ‘When I got to New Mexico, that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air, it’s just different. The sky is different, the stars are different, the wind is different.’ That landscape was her enduring love and her legacy, painted over and over in vibrant hues, under scudding clouds and pale blue skies.

By 1929, when O’Keeffe began visiting New Mexico, initially at the behest of Mabel Dodge Luhan, the arts patron who famously hosted D H Lawrence, she was already a successful and influential artist, known for her abstract work. She was married to Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and gallerist who first exhibited her paintings, and who became increasingly controlling of her career as her reputation grew. And she was tired of New York’s male-dominated art world, where critics often sexualised both her and her work. At her home in Taos, Luhan offered O’Keeffe greater independence in life and art. O’Keeffe soon began dividing her time between New Mexico and New York. Then, in 1949, after Stieglitz’s death, she made New Mexico her permanent home, staying there until her death in 1986. She chose to have her ashes scattered on Cerro Pedernal, which was visible from her home and which she referred to as ‘my private mountain’. She said: ‘God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.’

Some people still refer to Pedernal as ‘O’Keeffe’s Mountain’ and the land surrounding her Abiquiú home as ‘O’Keeffe Country’. I don’t. But some people do.

I would call Cerro Pedernal by its Tewa name, Tsip’in. I’m Puebloan, and Tewa is the language of my people, who have lived in and cared for our ancestral homeland of northern New Mexico since long before O’Keeffe visited. I grew up in P’o-suwae-geh Owingeh (Pojoaque), not far from the ancient Tewa village Avéshu (Abiquiú), where O’Keeffe lived for more than 30 years. My relationship with the landscape is rooted in a historical and spiritual connection. It is the backdrop to my most important memories, and holds the stories of my ancestors. My relationship with O’Keeffe is more ambivalent.

The New Mexico I grew up in was steeped in multicultural history – Feast Days and roasted pig at matanzas, Sonic Drive-In after school, lowriders on Riverside Drive. We didn’t have much money, but there was love and creativity everywhere. I spent summers in the Jacona hills, teenage years begging trips to the Santa Fe mall, hanging out in Walmart parking lots, and listening to my dad hum Al Hurricane while fixing the family car for the hundredth time. It was Puebloan traditions woven with 1990s and 2000s America – ceremony and MTV on the same day. A small world, but magical then and now.

My New Mexico is full of people. Full of history. It bears little resemblance to the empty spaces depicted in O’Keeffe’s paintings.

Like O’Keeffe, I feel New Mexico is uniquely beautiful. In her paintings, in the way she spoke about this place, I recognise a shared love of the landscape; yet the New Mexico I know feels worlds away from the one that has become so recognisable through her art. As someone Indigenous to northern New Mexico, when I look at O’Keeffe’s paintings, I can only see what and who she has left out of the picture.

Too often, discussions of O’Keeffe’s work strip away the historical, cultural and racist dynamics surrounding her life in New Mexico, as if she was the only person wandering the vast southwestern desert. I believe her work needs to be seen in the context of where and how it was made, especially since her work has come to symbolise a place she entered as a guest. I am not alone in this feeling. Many Indigenous and Chicano activists and academics are calling for a more well-rounded conversation about O’Keeffe that examines her work in a situated manner. In an article for the American Historical Review, Patricia Marroquin Norby, a curator of Native American art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, argues:

Foregrounding American Indian and Hispano histories, which are directly relevant to O’Keeffe’s Southwest images, demonstrates how her work aesthetically naturalised attitudes of Eurocentric entitlement and acts of colonial violence within the ancient Indian pueblo Avéshu (Abiquiú), New Mexico.

O’Keeffe’s work, in other words, renders those histories invisible.

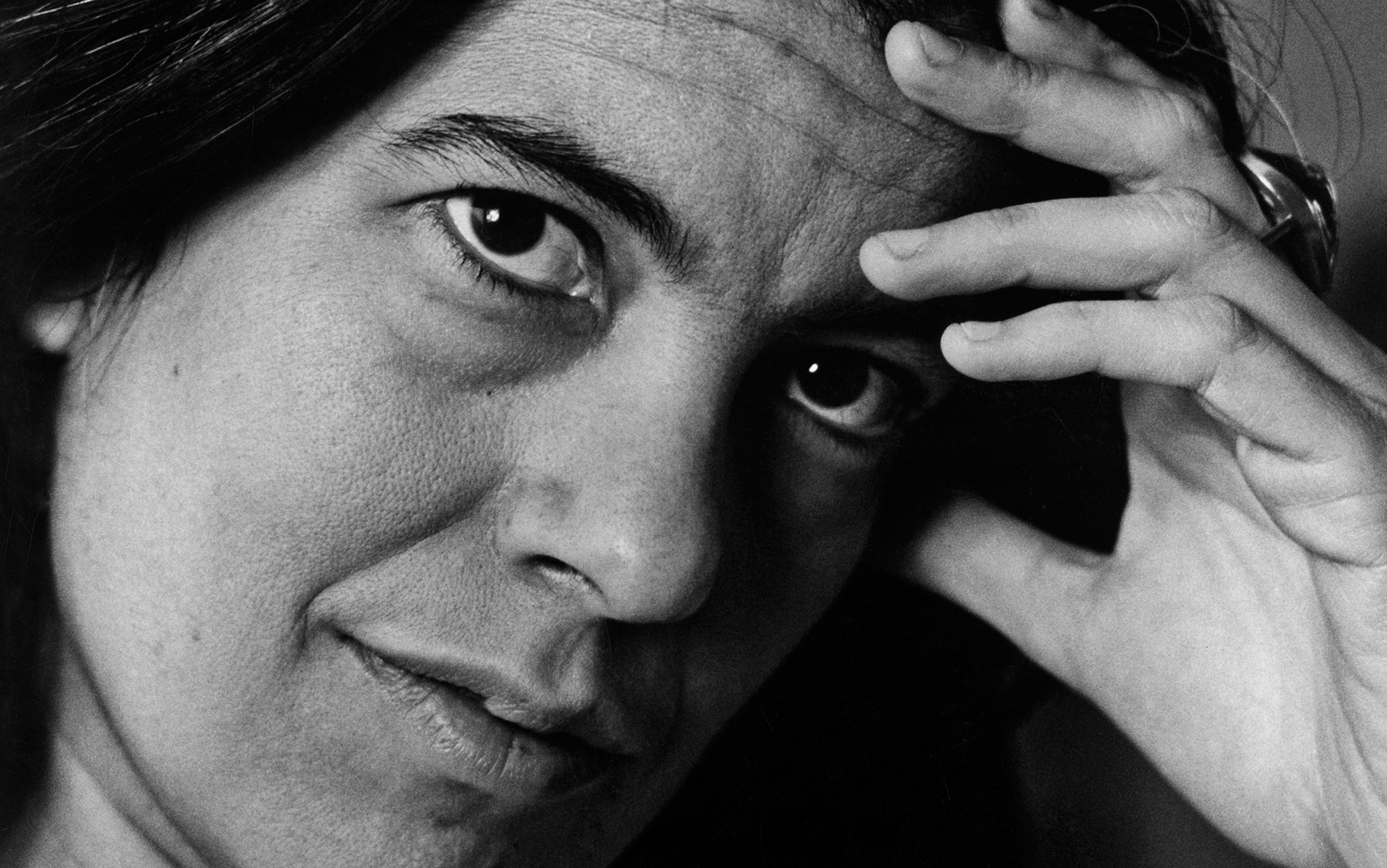

Georgia O’Keeffe was known to be rebellious and assertive, qualities I hope to nurture in myself

Successive waves of colonisation have suppressed and erased the histories of Indigenous and Hispano communities in the region. Moreover, the violence and land theft that made O’Keeffe’s art possible have barely been recorded. Yet, even holding this understanding, I still find myself resonating with elements of her artist’s journey. O’Keeffe is a feminist icon. Her career is an inspiration to many women pursuing careers in art, and I respect her independence and her commitment to shaping her life around her work. I admire how she reclaimed control of her own narrative after the death of her overbearing husband, and how she remained fiercely committed to her talent, and the value of her work. She took risks in both life and art in pursuit of her craft. I also appreciate that she was known to be rebellious and assertive, qualities I hope to nurture in myself.

These conflicting feelings about O’Keeffe coexist within me. You might see it as a weakness. You might think it makes me a bad Indigenous person. I won’t offer a resolution. I will likely complicate things further as I explore my relationship with O’Keeffe. But maybe it’s enough to lay these ideas side by side as they exist in my mind: true, and in opposition to each other. I think there is beauty in that.

New Mexico is marketed to tourists and residents alike as a place where Native American, Hispanic and Anglo-American communities have lived side by side in harmony for generations. Anyone who has grown up in New Mexico will tell you this is bullshit. Racial tensions and economic divides have existed since the conquistador Juan de Oñate rode into the region in 1598, marking the beginning of Spanish colonial rule: a year later, he led the Acoma Massacre, setting fire to the pueblo and murdering more than 800 residents. To understand my feelings about O’Keeffe and her representations of New Mexico, I feel it is important that you understand the history of the region and its people: my history and the history of my people.

Spanish colonists conquered Indigenous peoples and stole their land. These were the lands of my people, the Puebloan people, who had established villages like Abiquiú, where O’Keeffe settled, along the Rio Grande and its tributaries. Much of this land was then parcelled out as land grants to Spanish settlers, with little remaining available for Indigenous use. Communal land belonging to Hispano communities was then taken by the US government and Anglo-American businessmen following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The academic Sylvia Rodriguez summarises this process:

The federal government incorporated the merced common lands of vecino settlers into the public domain and acknowledged only individual or private property rights. It preserved the communal status of Pueblo lands, but exerted control by holding them in trust. This bifurcation ordained the different pathways of identity or ethnoscape construction that these neighbouring populations would follow to hold on to their adjacent traditional lands.

Our experiences with land loss, dispossession and forced displacement are embedded in our identity

While our people remained on the land, our relationship and engagement with it was changed forever through the experience of loss. This loss has shaped the way we feel about our neighbours and ourselves, alienating us from a way of life and cultural embodiment, not just place. As Rodriguez notes: ‘At the heart of modern Nuevomexicano identity formation is the paradoxical condition of being simultaneously displaced and place-based: a dispossessed, diasporic, deterritorialised, yet landed people.’ There are parallels here with the English enclosures, as well as with other histories of colonisation: we came to understand ourselves in relationship to what was lost, categorising our communities into ‘winners’ or ‘losers’ of the colonial game.

During the 19th century, the government encouraged Anglo settlers to move to the Southwest, easing their way through the Homestead Act and the construction of railroads, and displacing Indigenous and Hispano communities yet again, disrupting centuries-old traditions and ways of life. Artists drawn to the area’s stunning landscapes and ‘exotic’ cultures established colonies in Santa Fe and Taos, and, on their heels, Luhan followed in 1917, purchasing the large estate she called Big House, where she nurtured writers and artists.

New Mexico is unique in how its cultural, political and geographical isolation has contributed to keeping centuries-old Indigenous and Hispano traditions and customs intact, in the face of waves of colonisation. This has not been easy – our communities are in ongoing battles to protect and retain access to sacred tribal lands and waterways – but our continued presence and connection to the land is essential in maintaining our culture. New Mexicans have a term to describe this connection between place and identity: querencia. The New Mexican author, academic and advocate Juan Estevan Arellano defined querencia as ‘that which gives us a sense of place, anchors us to the land, and makes us a unique people’. How each individual defines querencia is unique to their lived experience. In the simplest terms, New Mexicans understand querencia to mean homeland, and the language and culture of our ancestors that is the foundation of identity. So, our experiences with land loss, dispossession and forced displacement are embedded in our identity as well.

O’Keeffe often spoke about the landscape in terms of ownership, and this is reflected in the titles of her paintings: My Red Hills (1938), My Back Yard (1943) and My Front Yard, Summer (1941). O’Keeffe’s possessive ‘mine’ implies a divine connection to the land, and often people discuss her connection to New Mexico using the vocabulary of spiritual belonging. It mirrors the language of manifest destiny, invoked by generations of colonisers to justify the taking of Indigenous land. If she was granted permission from God, then who are we to argue? But we will. Some might call it ‘O’Keeffe Country’, but we were here long before O’Keeffe arrived.

My Red Hills (1938) by Georgia O’Keeffe. Private collection. Photo © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

In 2020, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe hosted a panel titled ‘This Is Not O’Keeffe Country’. The museum’s director Cody Hartley opened discussions saying: ‘Georgia O’Keeffe did not own this area. She did not discover it. It is not a phrase we like or use any longer at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.’ Despite conversations like these, the State of New Mexico Tourism Department went on to use the term (and her infamous quote: ‘When I got to New Mexico, that was mine’) in a promotional video made in 2021. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum responded to the video, writing:

While these quotes are from the artist, it is now clear that this is the language of possession, colonisation, and erasure. Such language is offensive, insulting and insensitive. We strongly discourage the use of these problematic phrases, as well as ‘O’Keeffe Country’ to promote tourism or represent Northern New Mexico.

The image of a remarkable woman striking out alone in the desert ticks the boxes of a great American story. But the myth erases the peoples of Abiquiú

Indigenous community groups also issued statements about the tourism department’s ill-judged language. Speaking to the Santa Fe Reporter, the podcast host and museum professional Felicia Garcia said the department’s messaging

is representative of a broader effort to overwrite Indigenous connections to place … Colonial ideologies related to land and land ownership – such as manifest destiny, terra nullius and Western notions of private property – continue to harm Indigenous people. Indigenous place names, landmarks, stories, boundaries or lack thereof have been overwritten by romanticised US mythologies like this one.

Growing up in a rural area, I consistently heard my home referred to as ‘the middle of nowhere’. It was ‘empty’, ‘harsh’, ‘barren’. O’Keeffe used similar language when describing New Mexico. As Norby writes:

Alluringly haunting photographs of O’Keeffe strolling (almost floating) about the Piedra Lumbre basin highlighted her aesthetic and spiritual connection to the desert lands. They foregrounded the “vacancy’ of Abiquiú with descriptions of northern New Mexico as ‘vast’, ‘empty’, and ‘untouchable’ … O’Keeffe herself expressed a 20th-century colonialist attitude; in interviews, she played up the desert’s ‘wonderful emptiness’ …

But New Mexico was never empty. O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch property and the surrounding area have been inhabited for centuries. The myth of an empty New Mexico has had profound consequences for Indigenous and Hispanic communities, with one devastating example being the construction of Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1943. Hundreds of people were displaced to build these labs whose toxic experiments with explosive radioactive substances left sacred Tewa lands polluted and inaccessible to this day. The site was chosen because, like O’Keeffe, Robert Oppenheimer fell in love with the ‘isolated’ landscape he saw as largely uninhabited. Indeed, O’Keeffe and Oppenheimer likely crossed paths, since scientists from the labs are known to have stayed at Ghost Ranch under false names.

The image of a remarkable woman striking out alone in the desert ticks the boxes of a great American story. But the myth erases the peoples of Abiquiú, who tolerated her presence and whom she employed to maintain her home and property, allowing her to focus on her art. She could not have become an icon without them. Though her relationships with Abiquiú residents were sometimes strained by her lack of cultural understanding, there was mutual respect, and O’Keeffe donated generously to local organisations and individuals later in life. Norby notes that she’s remembered more as a quiet benefactress than as someone who recognised her dependence on local support. If she failed to acknowledge her dependence, she had some inkling of remaining an outsider. After almost 20 years living in New Mexico, O’Keeffe quipped: ‘I’m a newcomer to Abiquiú, that’s one of the lower forms of life.’

Even knowing all of this, O’Keeffe’s determination to escape the confines of gendered expectation resonates with me as a woman trying to find my own place as a writer. Speaking about an early moment of breakthrough in her work, she said:

I grew up pretty much as everybody else grows up and one day seven years ago found myself saying to myself – I can’t live where I want to – I can’t go where I want to – I can’t do what I want to – I can’t even say what I want to –. School and things that painters have taught me even keep me from painting as I want to. I decided I was a very stupid fool not to at least paint as I wanted to and say what I wanted to when I painted as that seemed to be the only thing I could do that didn’t concern anybody but myself – that was nobody’s business but my own.

This sentiment would stay with her throughout her career.

I wrestle with doubt. I worry if my writing is good enough, if this will make you think differently about O’Keeffe

I’ve been told my whole life that I’m a difficult woman – a know-it-all, full of myself, selfish with my time, stubborn about what I want to make. But difficulty, I’ve come to see, is not a flaw. O’Keeffe was the same. She guarded her privacy, demanded that attention was given to her work not her personal life, and refused to compromise her vision. She put creation above everything else. I admire that kind of clarity. I hope that, when I look back on my own career as a writer, I’ll see those same qualities – that I trusted my work enough to let it stand on its own.

Still, I wrestle with doubt. I worry if my writing is good enough, whether it meets the standards of my peers, if this essay will make you think differently about O’Keeffe. I know it doesn’t fit a traditional format with a tidy argument and solution. But maybe that’s the point. O’Keeffe pushed past self-doubt by believing in her vision. Her example reminds me to do the same: to focus on the craft, the impulse, the honesty of the work, and trust that it matters.

The idea for this essay came from a poem I wrote about O’Keeffe’s painting My Front Yard, Summer (1941), which depicts Cerro Pedernal, a subject she painted repeatedly.

Tsip’in

after My Front Yard, Summer (1941) by Georgia O’Keeffe

Empty summer weekends, I drove my new college friends to Abiquiú Lake

and taught them to pronounce Cuyamungue, Pojoaque, Okhay Owingeh.

We stopped at Bode’s General Store for 40s of malt liquor and cigarettes,

viejitos gawking at our tattoos asking que piensa tu familia.

I bought Marlboro Reds and my friends bought American Spirits.

I knew Pedernal’s outline like a neighbor’s silhouette behind a curtain. I was never brave

enough to test my footing on the chert, the mountain stayed a backdrop. Like a flat-topped

north star. Sunburned drunk off Olde English 800, we jumped from the cliffs, smacking

our bodies against the water below ignoring the stinging skin, noses choked with water.

Passing her house on the way home, I told my friends that Georgia O’Keeffe

said Pedernal was her own private mountain, that it belonged to her. She said God

told her if she painted it enough, she could have it. She loved Pedernal so much

she had her ashes scattered there. She painted it in every light.

Georgia, in another time, your dust up there could have been an arrowhead, a knife.

O’Keeffe was a flawed person seeking belonging, yet I still see her and her work as symbols of oppression

In her biography Portrait of an Artist (1980), Laurie Lisle says that O’Keeffe’s remark about Pedernal being ‘hers’ was said jokingly, and maybe it was, but I struggle to see the comedy. Pedernal dominates the landscape, and while I don’t believe O’Keeffe’s use of the possessive was literally meant, it reflects her colonial attitude. Pedernal is sacred to Puebloan and Diné people, and features in our stories and history. Every time Pedernal was in view, my dad used to tell me how our ancestors collected flint there to make arrowheads and tools. He would point out where ruins of our ancestors’ villages could be found in the area. He did this to remind me that our people have always had a connection to this land. Pedernal is our front yard. It belongs to New Mexicans.

At best, O’Keeffe’s work is one part of a long, evolving story. I’d like to have nuanced conversations about O’Keeffe’s time in New Mexico that open new ways of engaging with her work while recentring Indigenous and Hispano voices. My history is rooted in this place, so I hold all representations of it to a high standard. I cannot view her work in isolation, and I wouldn’t want to, since it would mean disconnecting from the people and land that gave me everything: the same land that gave O’Keeffe so much. I am fiercely protective of it.

In writing this poem and this essay, I’ve sought to balance my respect for O’Keeffe as a woman and artist, and my belief that her work erases my people’s history and culture. I don’t think balance is possible. Maybe it’s not even the right word when history is so heavy. I have laid these truths side by side because I believe the way they collide is worth examining. O’Keeffe was a flawed person seeking belonging, as we all are, yet I still see her and her work as symbols of oppression. At the same time, we share a love for New Mexico and a desire to live authentically. I hold my admiration for her alongside my resistance to what her art represents to me as an Indigenous person. It is messy, complex and imperfect. I think there is beauty in that.