‘It’s a very strange scene,’ Louise said, staring at the photograph, during one of our more recent sessions.

‘Can you make out what’s going on?’ I asked her.

She squinted and searched the picture. ‘There’s a little man over on the left side. He’s looking at a window in the middle of the room.’

‘Do you notice anything unusual about this photograph?’

‘I’m not sure, Dr Stanley. There must be or you wouldn’t ask it like that.’

‘What do you see, David?’ I asked her husband.

‘There’s a Volkswagen Beetle hanging off the ceiling, and a little boy is looking through the windshield. It’s an upside-down room.’

‘I guess so,’ Louise said. Her voice was flat and her face wooden with disappointment.

After retiring from her job as a social worker, for the past two decades Louise had pursued a second career as an artist and art teacher. During this time, she had also suffered from atypical Parkinsonism, a syndrome of the central nervous system that manifests as rigidity, slowed movements and problems walking. I was introduced to Louise in 2020. I’m training to be a neurologist, and her primary movement disorder specialist sent her to me, knowing my interest in art and the brain. The hope was that I could better characterise how Louise’s condition was affecting her sense of the aesthetic.

Parkinsonism didn’t just affect Louise’s movements. In the past few years, she had suffered from dementia, a progressive deterioration in cognition that affects thought, mood and behaviour. While Louise’s language and to some extent memory remain strong, in the past few years her chief struggle has been a decline in her visual and spatial abilities, and executive functions such as self-control and problem-solving. She could still identify basic shapes, silhouettes of animals, and obscure road-signs that I had shown her, and had even discerned a version of the Mona Lisa with an inverted face. However, a few hatches over a word rendered it unintelligible. A drawing of a hand with a superimposed spiral became a snail. Her vision could no longer pierce through a mess of extraneous details to the orderly form beneath.

I grew curious about the relationship between her steadily advancing cognitive deficits, and her creative will that never seemed to wane. Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that good art is a form of ‘dancing in chains’ – that restrictions and limitations (often self- or societally imposed) lead to workarounds and developments that spur creativity. In watching how Louise’s art and brain changed over time, I hope to show the role each played upon the other.

The story of Louise’s art began more than 20 years ago, while she was in her mid-40s. She bought a book at a rummage sale in Boston, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (1979) by Betty Edwards. Though Louise had never picked up a paintbrush, ‘lightning struck’, as she put it, and she knew she was going to be an artist.

An early exercise challenged the student to copy Picasso’s portrait of Igor Stravinsky, but upside down. Counterintuitively, the inversion made it easier to draw. To draw a well-known figure from a little-seen perspective drives the attentional systems of the right brain to focus on the forms and outlines that make up the figure – rather than the figure itself, who it is, and its details, which are a preoccupation of the left hemisphere. It’s a version of the art-school adage to draw what you see, not what you know you should see. Even so, the two are hard to separate, since the brain’s ‘top down’ expectations influence what stimuli arrive ‘bottom up’ from our environment.

Louise attempted the exercise and, to her surprise, it looked like Stravinsky. Her pleasure in copying the portrait lay not just in the creation itself, but in the act of creation. Most of us experience the joy of art only in appreciating it; our minds put together the scene before us, link it to our past, and focus it with our mood in that moment. Two people might cry at a Rothko, one from pleasure and one from confusion. Louise found joy in setting that process into motion as an artist, producing something that marshalled the viewer’s visual stimuli such that she and others would react to it. She was going to be a creator, not just an observer.

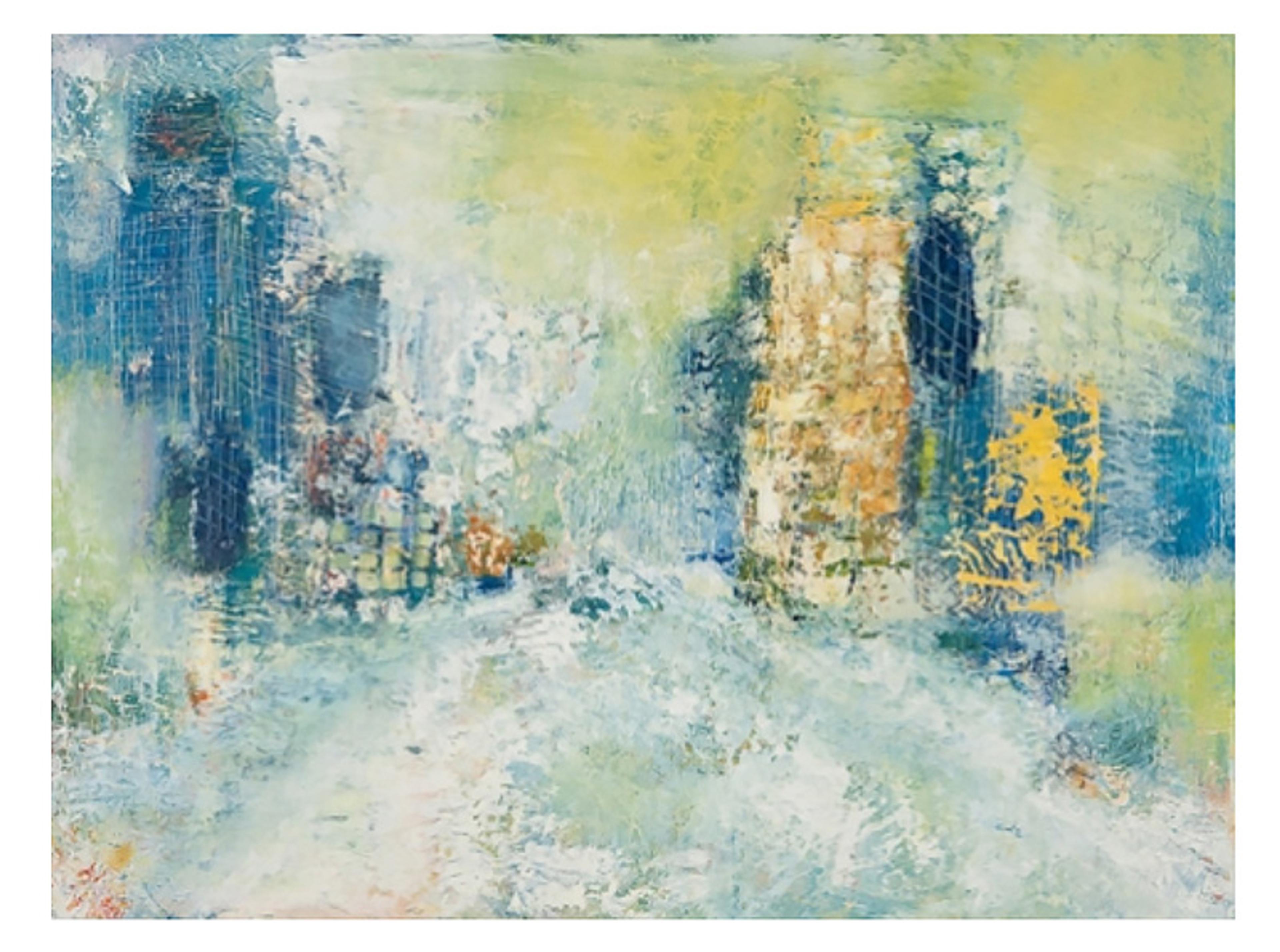

Intersection (2010) by Louise Weinberg

Soon, Louise’s urge for expression drove her to abstract painting. Oils appealed both for their aesthetic and their textural feel. She used bold colours on large canvases, trying to explore relationships of space where viewers could begin to project a sense of figure (a street corner, a table), and yet… was it really a street corner? More than beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The artist tells us where to look and controls what we’re looking at, but what we see is a perceptual process that happens in our brains and not on the canvas.

Too little dopamine can lead not just to rigidity of body but of thought, with apathy and depression

Eventually, Louise enrolled at an arts institute in New England. Initially, she could paint all day with no more than a bathroom break or a bite to eat, but over the first year of her formal art degree she began to sit down and rest for longer stretches. There came a day she couldn’t work for even an hour without stopping to recover. Looking over her day’s labour, her once-flashing strokes had become stiffer and smaller. This new ground-down feeling served as a literal drag on her painting. To accommodate this impediment, she switched from large abstract paintings of sweeping arcs and took up hyper-realistic depiction, putting her small strokes to use. This collection was titled, prophetically, Coming Apart.

Coming Apart (2003) by Louise Weinberg

Louise’s painting wasn’t the only part of her life that was suffering. She had become more uncoordinated, unsure of herself even on level ground. Sometimes she felt frozen to the floor. After seeking out a neurologist, she was diagnosed with atypical Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism is an umbrella term, a syndrome of features, but its cause can vary from drugs, infections, strokes and degenerative conditions, like the more commonly recognised Parkinson’s disease. All forms of Parkinsonism result from a deprivation or blockage of the neurotransmitter dopamine within the basal ganglia region of the brain – the part that helps stop movements or get them started in a hurry. Dopamine also regulates several neural networks relayed through the basal ganglia and beyond – these networks facilitate movements, but also affect mood and reward-signalling, too. Too much dopamine can lead to extra and involuntary movements (dyskinesia) as well as addictive and compulsive behaviours, even psychosis. Too little can lead not just to rigidity of body but of thought, with apathy and depression.

Standing Room Only (2010) by Louise Weinberg

Once Louise started taking a dopamine supplement called carbidopa-levodopa (Sinemet), she regained the dexterity and stamina that her artwork demanded. The levodopa part of this combination drug gets converted into dopamine, while the carbidopa helps to stop it breaking down before it reaches the brain. Aided by this dopamine boost, Louise began creating larger, complex abstract pieces exploring fields of colour, forms and lines. Her exhibitions sold well, even becoming backdrops in movie sets, and she gained the confidence to teach art in adult education programmes.

Louise continued to draw figures to her own satisfaction until 2011, about nine years from initial diagnosis. Her drawings consisted of both human and animal figures (with a particular soft spot for dogs). For now, abstraction in painting was her choice. Forays into perspective – atmospheric gestures of landscapes or still lifes – could be frequently found on her canvases. She also painted on polymer sheets, which she began to prefer because of their lower resistance to her brush.

As her Parkinsonism progressed, Louise was taking Sinemet up to nine times a day in order to paint for five hours and lead an active life. That was in addition to direct dopamine agonists, drugs that look like dopamine and smooth out the on-and-off periods when Sinemet fails. But dopamine agonists are notorious for side-effects on mood and behaviour – particularly addictive and hyper-sexual behaviours. As doses were increased, she struggled with impulse control: calling loved ones as soon as the idea struck her, or being glued to the computer screen for hours. By 2015, she started exhibiting cognitive symptoms that couldn’t be explained away as side-effects of Sinemet. She crashed the car repeatedly, and her husband David noticed that she drove extremely close to other cars. That loss of capacity to judge spatial relationships couldn’t be attributed solely to slow movements and poor reaction times. She started to have short-term memory loss – but, being in her 60s, that was not uncommon in the ageing process.

Then Louise started to experience illusions. One day, she told David how frightened she was of a strange, silent man sitting in the living room. He just sat there and never responded to her questions about who he was or what he was doing. Eventually, she worked up the nerve to walk over and reach out to him. It was only when her fingers felt the fabric of a coat, slung across the chair, that she realised her vision had misled her.

Soon these apparitions became commonplace. The folds of a pillow looked like a face, a pile of clothes transformed into a strange dog. Profiles percolated out of vases, and coat-racks came alive as intruders. Louise didn’t just misconstrue objects: she started to misidentify people, recognising strangers as somehow familiar, and seeing her family as doppelgängers.

If others could see what she saw, then she might not be so alone in her world

The irony was that illusion, though less dramatic, was a crucial feature in the figurative art Louise had drawn for years. To ‘see’ a portrait of Stravinsky, we must ‘misinterpret’ stains on a board – drawing inferences about patterns of shape and colour that allow blobs of paint to cohere into defined forms. These blobs and lines become bound into whats and wheres, which conceal whys as well. The neuroscientists David Milner and Melvyn Goodale helped cement our understanding of ‘what’ and ‘where’ networks in the brain in the 1990s, though, intriguingly, the art historian Ernst Gombrich made a similar what/where distinction in The Sense of Order (1979). We can’t see a countenance without discerning the emotional valence of its expression. We begin to guess why that face looks pained, angry, sad, and, if a character gestures elsewhere in a painting, our eyes follow the illustration’s direction.

Perspective like this is not a passive act. It’s a complex process of focusing, filtering and fitting what sensory stimuli are available into the reality that our brain has come to expect. Senses such as vision and hearing might be separated at their sources, but our mind combines these inputs to create a model – a working illusion – to explain what’s going on. As a consequence, our perception readily adapts the present to what we expect of it. Camouflage deceives the gazelle, who expects to see long grass and so overlooks the lioness. It isn’t until something reaches a certain bar of sensory improbability – long grass shouldn’t smell like a lion, it shouldn’t move against the wind – that the integrity of the illusion is challenged and revised.

Such illusions are not just for navigating frescoed walls, then, but also let us navigate reality in our everyday lives. When parts of that processing deteriorate, what remains is maladapted to making sense of everyday life. It might not be ‘correct’ but it will still try to be coherent. Louise now misinterpreted stimuli she previously would have filtered out as background noise, such as wrinkles of fabric or shadows on the wall. Her acceptance of the existence of faces instead of inanimate objects (known as pareidolia) was a frightening betrayal of the shared illusion the rest of us might call the world. To cope, Louise soon learned to live with her impressions by depicting them. Art historians such Gombrich were influenced by perceptual psychologists such as J J Gibson and Ulric Neisser, who proposed a perceptual cycle where we see in order to act on what we see. Here, Louise’s life and her art served as a living link between Gombrich approaching perception from an art-historical side and Neisser approaching perception from a psychological angle.

In observing Louise’s decline, she and her husband decided to capture Louise’s reality as best they could. A capable photographer, David listened to Louise’s descriptions and developed a series of compositions that showcased the bizarre transmogrification of her surroundings into people and animals. If others could see what she saw, then she might not be so alone in her world.

Hallucination and Chair (undated) by Louise Weinberg

For clinical visits with her neurologist – the one who referred her to me – Louise would arrive without having taken her Sinemet, so they could see her at her worst. Her rigid arm would click almost like a cogwheel; her gait was shuffling; and her face was muted at best; at worst, sad or tearful. Then she’d take her Sinemet, and within minutes her expression brightened and her limbs were freed of their invisible sandbags. Too much Sinemet, though, and she squirmed uncontrollably with dyskinesia.

At about the same time as illusions began to trouble her, Louise started to hear music that no one else could, and she still does. It’s a limited jukebox of the same tunes over and over, ditties her mind composes on its own, looping for hours. It used to annoy her, as they come and go on their own, but nowadays she seems entertained by these psychic serenades.

On Your Marks, Get Set, Go (2014), from the Games Fish Play series by Louise Weinberg

Coinciding with the onset of her illusions and hallucinations, Louise abruptly departed from abstract painting and moved to the subject of still lifes – something she hadn’t done for years. These might be still lifes, but they’re certainly not real lifes. While the plant, lamp, fruit and bowl cast shadows, the floating fish do not. In her series The Games Fish Play, fish intrude upon the usual fare at a dining-room table – or is it the other way around? The perspective is disorienting.

It was a compulsion to paint and repaint. Sometimes only exhaustion stopped her

Disorientation and problematic perception became themes in Louise’s personal life. She was having increasing difficulty paying attention, staying organised, and remaining oriented. Yet other cognitive domains such as language, memory and self-perception remained relatively spared. All this meant she was quite aware of her fading capacities. As she neared the next dose of Sinemet, anxiety seized her: if there were any delay, she would swiftly slip into a depression and ossify into a stiff, slow simulacrum of her former self. After taking her Sinemet, the depression would lift, and Louise would be happy again – or, at least, capable of being happy. When she was ‘on’, she was in many ways back to her old self.

From the beginning, her style was loose, welcoming to accidents that brought new shapes or colours. Like many artists, Louise enjoyed discovering different textures and unexpected effects. As her Parkinsonism progressed, however, she could no longer hold a brush. She switched to a palette knife for the next few years. Stylistic choices weren’t always conscious, deliberate decisions. But is that so different from other artists? New forms and styles derive in part from necessity or accident in handling new media, new technology or a new quality of that medium, or even working with its deficiencies. In Louise’s case, it was a change of mind and not material that brought about shifts in her style; even the response to that change might not be intentional. Volition, whether motion or emotion, is affected in diseases of the basal ganglia, and David was careful to watch over her sweeps with the knife. Even so, switching to a palette knife didn’t involve a degeneration in her technique but rather a progression in the purity of her aesthetic. Involuntary or not, Louise liked the product and the new elements it created, learning to blend it in with her compositions.

Work in progress (2015) by Louise Weinberg

One of the artist’s chief responsibilities in creation is knowing when the work is done. Many works have been ruined by overworking. In the past, if she could, Louise would happily paint for hours, but on different projects, putting one aside when finished to begin another. But now she persisted on a single work, overworking it for hours until, in hindsight, she realised she should have stopped. A few times, her studio assistant and David had to physically remove a painting so she would not ruin it by continuing to paint. It was a compulsion to paint and repaint. Sometimes only exhaustion stopped her.

In 2017, out of the swirl of abstracts she had been producing, human figures tiptoed into her inspiration with a series called The Girls. She never met these girls. They were not her illusions. The artist’s note for the series – the last she wrote unaided – was titled Am I My Mother. This hints at her own mother’s struggle with dementia, but mostly focuses upon the role of imagination in saving us from isolation and allowing us to act out roles we haven’t been picked for:

Growing up as an only child in New York City, I was aware that I would never know what it feels like to have siblings. I spent my lonely childhood creating imaginary playmates … The playmates were always girls. My fantasies filled my childhood with happiness and love. In my play, I floated back and forth from the roles of parent and sibling, never questioning how this could happen. The role changes may have seemed confusing to others, but not to me.

‘My girls’ disappeared when I was about 12 years old. I tried desperately to bring them back, but they never returned. I was left to ponder, as an adult, about the amazing ability of children to self-comfort through imagination. Or… I suppose I finally no longer needed them, but I still miss them.

From The Girls series (2017) by Louise Weinberg

At this point, Louise was no longer able to paint with a palette knife. Instead, driven on by this indwelling desire for the creative act, she began to paint the girls with her hands. Consciously, she says she switched to using her fingers because she liked the feel of the paint, and she enjoyed the repetitive aspect of making ‘dots’ with her fingers. Like the tunes running on repeat in her head, the repetitive exerted its hold, even in her technique. Whether in process or product, she wasn’t just inspired, but compelled.

Louise’s diseases facilitated possibilities and limitations in her art

The act of perceiving is the act of making sense of our world. Perhaps Louise’s emphasis on and justification for less control in her technique, and the continual small dotting, were a reflection on the fact that she possessed less control, physically and mentally, over her world. On the other hand, any style involves coordination between the executive function that an artist imposes on mark-making, and the natural rhythms (breathing, heartbeat, tremor) that impose their own limitations or advantages for performance. Sergei Rachmaninoff could compose songs only he could play because of his absurdly large hands (perhaps a mark of a genetic disorder such as Marfan syndrome). Louise’s diseases facilitated possibilities and limitations in her art, too: influencing the placement of her hand, the speed and coordination of it, and its relationship to the very space she plans to fill with colour.

Louise’s progression from brush to palette knife to hand is in one sense a regression. Yet in another way, it’s a pilgrimage to the primal artistic act and the purity of its intent. Children paint with their fingers, and what their work lacks in naturalistic depiction it excels in primal symbolism. Why such symbolism should be more readily produced when the tool is a hand and not a paintbrush is intriguing. What we feel physically/externally and what we feel psychically/internally appear to come into closer proximity with fingerpainting. In mark-making with one’s hand, the human body itself becomes the tool for expression, and that tool is a sensitive limb. The haptic is different from the other senses in the seamlessness of its sensory and motor processes. We finger a coin in our pocket, and that motion yields sensation, which provokes further motion until the desired object is discerned. We move a limb that feels, and that motion is what stimulates the sense of touch.

If we think back to Louise’s selection of oil paints, she liked ‘the feel’ of them in a tactile sense, but also in the more abstract visual feel of the resulting composition. Now, working with the paint at the tips of her fingers and pushing it across the paper, Louise is as close to truly feeling a visual medium, in both the motive and emotive sense.

By 2018, Louise’s hallucinations had become more frequent, frank and terrifying. Strange men sat on her couch, little girls stood with her in the shower, and sometimes doppelgängers of her husband joined the couple for dinner. She once saw a hallucination of herself, and sometimes replicas of her own children. Over the ensuing years, these became constant fixtures – a kind of mental staging somewhere between background and foreground in her field of view. Her husband has heard her say, with either surprise or exasperation: ‘There’s no one here!’ It became unusual for her not to be hallucinating.

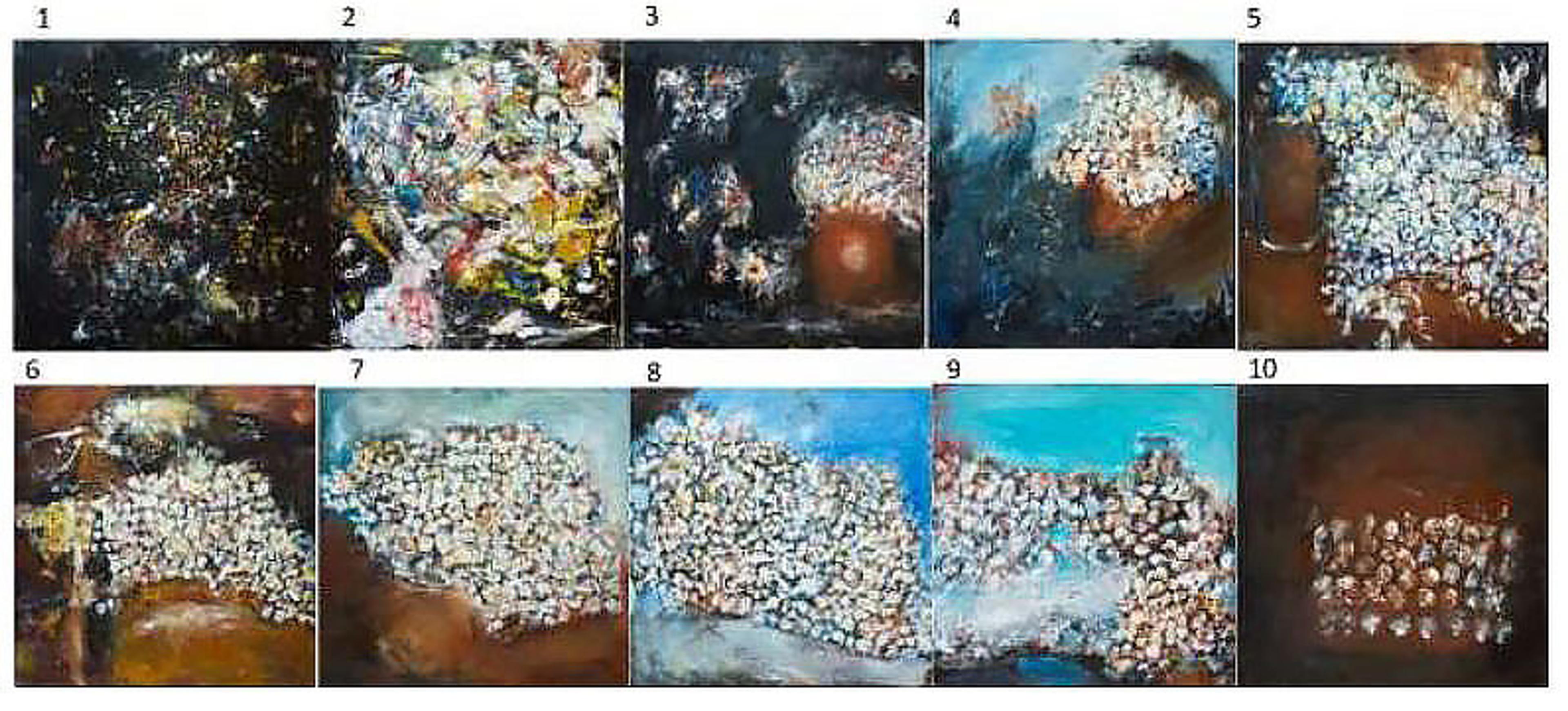

After The Girls, Louise began a series intended initially to be a collection of still life paintings. First came two pieces that were intentional abstractions – From Darkness to Light, the theme of the series. These were two wild explosions of colour. The next painting was an earthenware vase bearing a bouquet of tiny white flowers. With each successive attempt to portray this still life, however, Louise’s style began to loosen, then untangle completely. The still lifes swelled into splendours of abstraction before burning out into amorphous tongues of light, scraped across a rust-coloured background. Perhaps Frames 1 and 2 were drafted during ‘on’ periods, times when the dopamine delivered by the Sinemet overwhelmed the basal ganglia, resulting in too much movement and too much concentration to the point of overworking the piece – whereas Frames 3 and 4 are products of a Goldilocks dose, when just the right amount of dopamine via Sinemet allowed for enough range of motion but a balance between attention and freedom of expression. And yet, the subsequent frames can’t be so easily explained by dopamine fluctuation. The way the flowers devolve in their individualised forms, while at the same time amassing into encroaching blobs upon the rest of the piece, until finally the form fractures into little puncta – that seems like painting from life, a life that you’re no longer able to see clearly.

The Darkness to Light series by Louise Weinberg

Along with hallucinations, Louise was plagued by delusions. There’s a spectrum from hallucinations to delusions, a movement from perception without a stimulus towards conception without a reason. She thought someone was coming into her studio painting over her paintings. She pointed to a jet-black canvas to prove it – a canvas she had painted over and forgotten. She would see people up in the trees or hear parties out on the lawn. This was the case even if they weren’t directly in her line of sight; and, after being apprised of the irrationality of these ideas, Louise said she nevertheless felt they were there. Felt expresses an experience somewhere between sensation and sense.

I am not only a neurologist or only a humanities scholar, and Louise is not only a patient or only a painter

Louise was now routinely painting over her previous works, and seemed oblivious to the fact there was anything there to begin with. She could no longer recognise work as her own. In 2020, without sufficient cues, she often didn’t recognise family in COVID-19 masks. One day, her husband was standing in front of the TV, holding a coffee cup, watching the former US president Barack Obama giving a speech at a Joe Biden rally. Louise looked at the screen, with her husband and the coffee cup in the way, and said: ‘Oh look, Obama’s drinking a cup of coffee.’ She could correctly name the colours of objects on the table before her, but at times her world became hyperchromatic. The water in her sink would glitter a celestial blue, and sometimes her whole world filtered through a tinted lens. She has not chosen colours in her art based on this lens effect, but it did interfere with her compositional skill, as it was sometimes difficult to discern what colour was on the canvas and what colour was in her cortex.

If You Could See What I See (2019) by Louise Weinberg

In the past few years, Louise went from obliviously painting over her work to consciously tearing it up. No longer able to paint, increasingly dissatisfied with her drawing, yet still compelled creatively, she began to collage from these torn remnants of her previous work. She now required physical assistance from a friend. Over 18 months, she managed to make 10 collages. She destroyed paintings and sorted scraps, her friend pinning them to a board so Louise could shuffle the pieces about until the configuration pleased her. The last of her public shows was in 2019: If You Could See What I See, in which she expressed, with David’s help:

I have arranged fragments cut from her drawings and paintings into collages that spring from my unconscious. I added, subtracted and rearranged the pieces until forms and colours emerged that speak to me – an act of creative destruction … While hoping for improvement, we decided to turn this adversity [her Parkinsonism and dementia] into a creative opportunity.

Louise’s work had become an act of creative destruction. Like the perceptual act of toggling between a duck and a rabbit in the philosophical illusion, the selection for one negates the other. But Louise’s inability to perceive in one capacity didn’t exclude her ability to see in new creative ways. The visual system continued to be pressed into service of an intent. Despite her distortions in vision and disorders in thought, her artistic impulse – that intuition stretching all the way back to the upside-down Stravinsky – has compelled her to create, even if such creation comes at the cost of destruction.

Louise’s art can’t be divorced from her disease, but nor is it determined by it. In collage, a meaning manifests as a whole from broken pieces and fragmented ideas. Mark-making is meaning-making, as the art historian David Rosand pointed out. So, by exploring the meaning of Louise’s work, we experience her meaningful world.

As a neurologist, I can describe her deficits and try to localise them, finding the source of her confusion in specific brain networks. But this piecemeal and reductive approach to Louise is ultimately an unprofitable lesson in neuroanatomy. Similarly, a pure art-criticism approach might find, in the end, a career that devolved in technique and composition rather than excelled. But I am not only a neurologist or only a humanities scholar, and Louise is not only a patient or only a painter. We are a totality of our experiences – not unlike one of her collages. And scanning the varied techniques she used to adapt her painting to her experience, rather than the other way around, I’ve come to better understand that, while her style might be influenced by its symptoms, her power to paint transcends them.

Sadly, Louise passed away shortly before the publication of her story. The author wishes to dedicate the piece to Louise and her husband David, who welcomed him into their lives to share a new and richer perspective of the meaning of artistic vision.

To read more about creativity, visit Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophy and the arts.