In 1978, the science-fiction author Michael Moorcock wrote the celebrated essay ‘Epic Pooh’ that lambasted J R R Tolkien and his ilk for constructing fantasy universes in which – whatever the ‘there and back again’ meanderings of the plot – nothing ever really changes. Moorcock felt that his own ‘new worlds’ science fiction of the 1960s was a radical intervention for producing difference, while the fantasists were essentially nostalgic for a past in which everything had its proper place: the king on his throne, the dragons slain, the ordinary hobbits happy with their pastoral lot.

We have a lot of this fantasy futurism nowadays, with the armies of good and evil being arranged on opposing sides of the wall, or across a rift in the time-space continuum. Jon Snow and the New Avengers will come to save us, swinging swords to ensure that everything stays pretty much how it was before Voldemort, Sauron or the White Witch started messing things up. Fantasy is not really that fantastic, essentially because it takes a set of tired archetypes, adds a bit of sex and chopping, and then delivers a message about singular heroes, villains and obstacles. The Marvel Universe, currently at 23 movies, will soon be overtaking James Bond as the biggest film franchise of all time. Add in comics, TV and games, and you have a huge investment in the idea that we need heroes to save us. As flies to the gods are we.

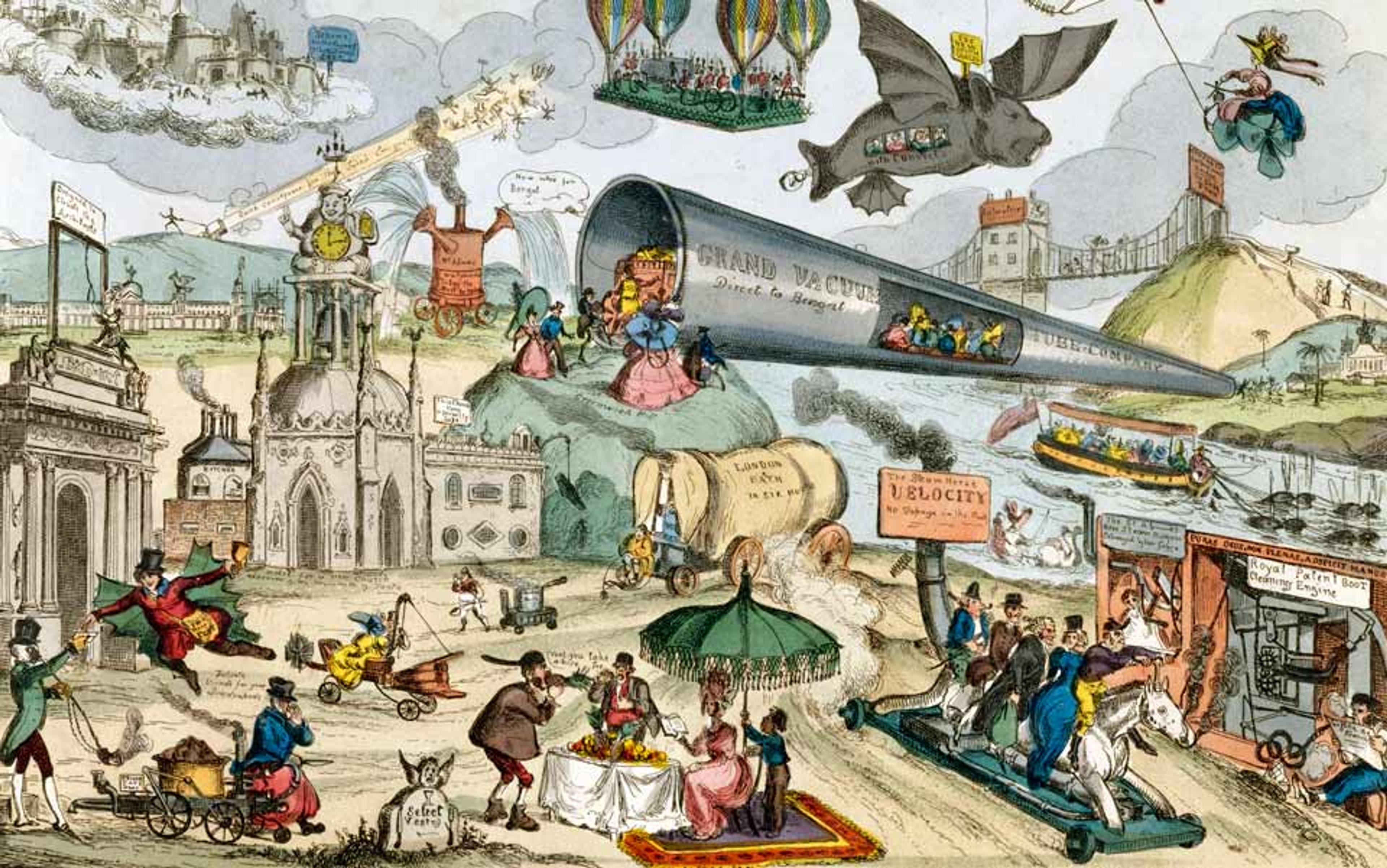

Perhaps this cultural leaning isn’t about the future at all – just the recitation of comforting stories from long ago and far away to lull us to sleep. Real attempts to describe (and realise) human futures have always been more dangerous. What we now call the Enlightenment made curiosity possible, even celebrated, instead of thinking of it as a sin to be punished. At the same time that ‘utopian’ fiction was invented, we find attempts to produce a new sort of mercantile world, in which the timeless sclerosis of hierarchical feudalism was gradually eroded by the speculations of projectors, inventors and adventurers who built new organisations and machines.

Later, the ingenuity of the Industrial Revolution was predicated on the coordination of people and things at scale, towering mill buildings and a rail network that compressed space through the precision of the timetable and technology. This was organising on a grand scale, and it required the coordination of people and materials in ways never imagined before. In the 20th century, the Empire State building, the Apollo space programme and the supersonic gee-whizzery of Concorde are emblems of a future in which nothing could ever be the same again. These were grand projects of massive complexity, auguries of a modern world, and they drew their strength and efficacy – and, not least, their imaginative purchase on the future – from the new science of management.

In English, the word ‘management’ has an interesting history, and some rather productive differences of meaning. It is derived from the Italian mano, meaning hand, and its expansion into maneggiare, the activity of handling and training a horse carried out in a maneggio – a riding school. From this form of manual control, the word has expanded into a general activity of training and handling people. It is a word that originates with ideas of control, of a docile or wilful creature that must be subordinated to the instructions of the master.

It’s a really interesting word that grows in influence and application as the feudal order of fixed social relations based on ownership of land is disturbed by the rise of a mercantile class. This bourgeois revolution rested upon a relationship to capital, of which land was only one element, but it relied as well on more complex forms of production and distribution, and consequently on organisations with more elaborate divisions of labour. Localised craft economies were displaced by manufactories, machine production, urbanisation and also longer distribution networks via canals and trains. Its practice is fabricated in the ‘dark satanic mills’ that romantics and radicals were keen to condemn for the brute people and despoiled landscapes that they produced.

But the later imperialism of this beast-handling word doesn’t tell the whole story. In English, the earliest use of ‘management’ was as a verb that could be applied to the need to deal with complex or adverse matters, and it is the oldest usage. In Richard II, written in 1595, William Shakespeare has Green say: ‘Now for the rebels which stand out in Ireland,/Expedient manage must be made, my liege.’ The word could mean something like careful planning, necessary in this case because of the complexity and danger of that which was being faced.

The future has been displaced into the soma of fantasy

The London Encyclopaedia (1829) has an entry for ‘Manage’, which suggests that it is:

an obsolete synonyme of management, which signifies, guidance; administration; and particularly able or prudent administration of affairs: managery is another (deservedly obsolete) synonyme of this signification: manageable is tractable; easy to be managed.

This sense of management as coping, as dealing with a particular state of affairs, is still passable in everyday English. You might ask ‘How are you managing?’ if someone has told you about some problem they face. To organise complex matters, to arrange people and things, to be resilient in the face of adversity, now that requires managery. This second meaning, not distinct but different in emphasis, emerges in the 19th century with the class of people called ‘managers’. These managers do management. And as this occupational group grows throughout the 20th century, driven by the growth of the capitalist corporation, so the business school expands to train them.

At the present time, that sense of managing as the art of ‘organising’ to cope with challenges is largely obscured by the idea of the manager as someone who helps to create financial value for organisations, whether they operate in state-engineered pseudo-markets, or the carbon-max madness of global trade. This means that questions about what sort of future human beings might create tend to be limited by the horizon of the management strategies of market capitalism. This version of the future isn’t about radical discontinuity at all, just an intensification of the business practices that promise to give us Amazon Prime by drone at the same time that the real Amazon burns. This is what they teach in business schools – how to keep calm and carry on doing capitalism. But the problems we face now are considerably bigger than a business school case study, so is it possible to rescue managery from management?

Captain Marvel and Thor aside, the other set of gods that dominate our futures are the business school heroes – Bezos, Musk, Zuckerberg and many others. Amazon has made Jeff Bezos the wealthiest of them, personally worth about $138 billion dollars currently, and with a company that now seems to own the world. Close behind him, perfecting his Tony Stark-Iron Man look is Elon Musk, busy making our futures with Neuralink, Tesla and SpaceX. Geek-lord Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook doesn’t actually make or do anything: the enterprise just collects information that allows it to sell advertising. These are the unicorns, the people who started a business in a garage and now live in fenced compounds overlooking some canyon or other. Their future is one in which you keep paying so that people like them can keep selling you things you didn’t know you wanted.

In the hands of technology entrepreneurs, driven by the imperatives of shareholder value and richer even than the robber barons of a century ago, the future has been displaced into the soma of fantasy, colonised by people who want you to pay a subscription for an app that helps you sleep, a delivery service that allows you to stay indoors when it’s wet out, or a phone that switches on the heated seats in your car before you leave home. This is a future of sorts, but it’s a business school version in which everything is pretty much the same, just a bit smarter and more profitable. It’s being sold to us in adverts at the cinema and in pop-ups on our screens, as if it were the real future, but it’s not. For something to count as the future, for innovation to be as inspiring as the Eiffel Tower, Apollo or Concorde, it must promise something that has never been before. It must be a rupture, a break in the ordinary series of events that produces a future that is altered in profound ways, and something on the horizon that is unknowable, but different.

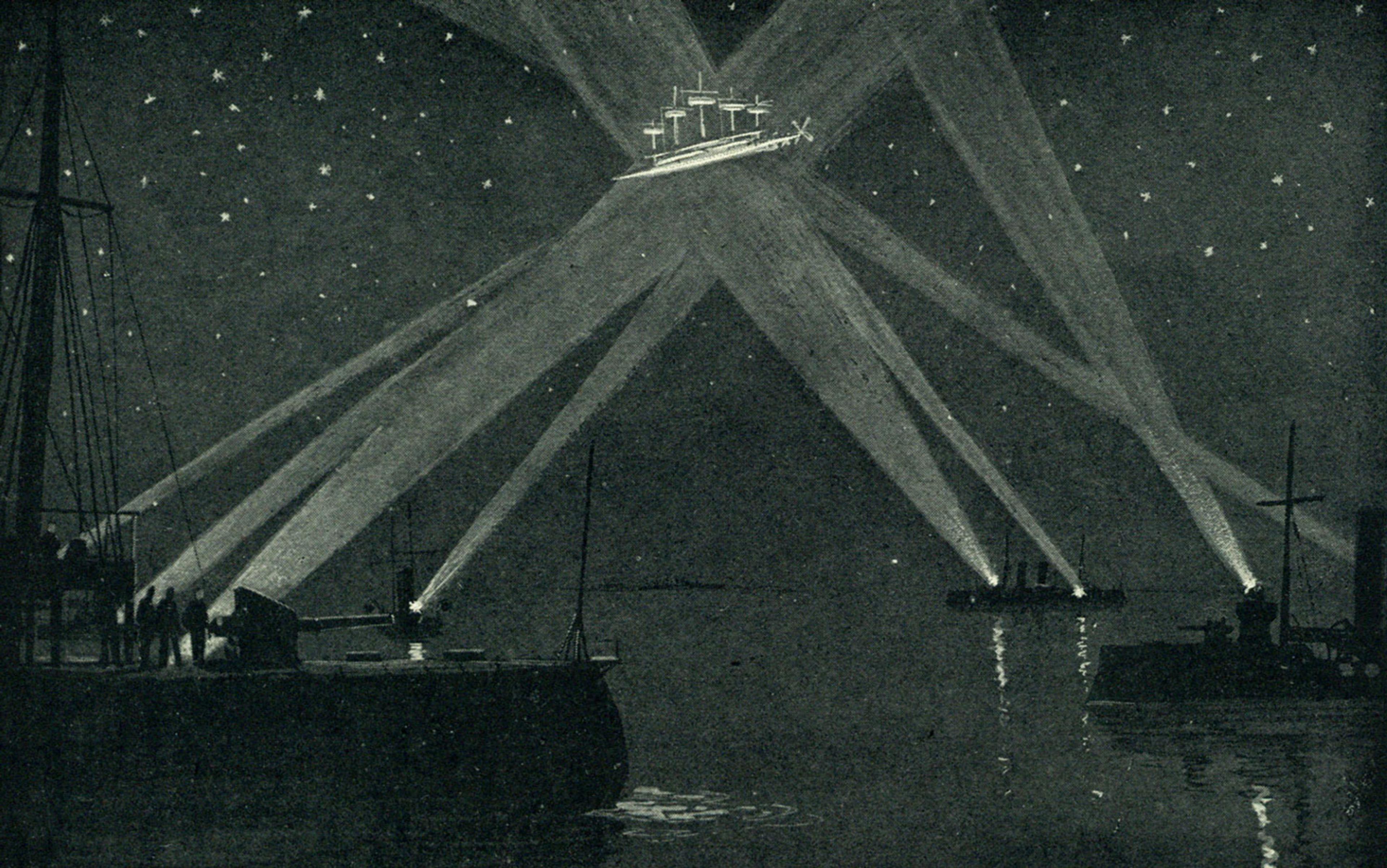

The historian David Nye in 1994 captured something rather important about how we think about the future when he coined the phrase ‘technological sublime’, drawing on Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), which provided a compelling rationale for exposing oneself to the awe-fullness of nature. If smallness, delicacy, fragility, smoothness, sweetness and gradual variation were characteristics of the beautiful, then the sublime was characterised by vastness, darkness, danger, power, infinity and suddenness. It is because, Burke suggested, these qualities remind us of our mortality and insignificance that exposure to the sublime provokes such strong emotions. Towering mountains and crashing seas stir us to a greater degree than tranquil pastoralism, and call forth in us dramatic, even heroic feelings, which in turn inspire our grandly romantic sense of quest, spirit and dreaming.

Nye’s 20th-century version of the sublime is the airship, the Hoover Dam, the skyscraper, the railroad – magnificent mountains of steel, grand architectural projects, incredible distances and speeds. These technological feats became symbols of national pride and fuelled prophecies that nothing would ever be the same again. A particularly American version of the future was everywhere from the 1930s onwards with pulp sci-fi writers selling stories to magazines called Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories of Super-Science – visions that later became radio and then TV shows, boldly exploring where no man had been before. And for me, growing up in England in the 1960s, it was the Apollo space programme, and then Concorde, that looked like splinters from a new world, somewhere just around the corner.

The Moon landing was also a huge exercise in New Deal economics

In 1968, James Edwin Webb, then ex-administrator of the US space agency NASA, delivered a series of McKinsey Foundation lectures at the Graduate School of Business at Columbia University in New York, which were published under the title Space Age Management the next year – but before the Moon landing of July 1969. Webb had been schooled in Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal administration and was an advocate of grand-scale government intervention, big projects to change the world. At that time, ‘space age’ was a prefix that was being applied to everything. Effectively, it meant something like ‘modern’, and the coupling of ‘space age’ and ‘management’ in his book combines this sense of modernity with a particularly technocratic sense of control. The space age was going to be an age of mass organisation, of pills instead of meals, of new products that saved time, and of factories and offices and launch pads connected by freeways and telephones. It was a world of harmonious organisation, managed by wise and well-qualified elders who would deal with our problems by organising the world in a better way. It was the shape of things to come.

In order to achieve John F Kennedy’s goal, articulated in 1961, of landing men on the Moon before the decade was out, huge numbers of people, things and places needed to be made, coordinated and controlled. In 1966, NASA directly employed a staff of 36,000, with another 400,000 people working for 20,000 contractors and 200 universities in 80 countries. Such numbers are almost unimaginable today. It meant that Webb needed to account for people and things, chains of command, scheduled meetings with determinate agendas, as well as plans, predictions, reports and deadlines. The Moon landing was a triumph of organisation, of project management and control of a huge and complex sociotechnical system. It was also a huge exercise in New Deal economics, with a wide variety of state subsidies being channelled through NASA to aerospace corporations, universities, local regions and so on. The contradiction between ideas of individualism and the free market and this taxpayer-funded technocracy didn’t go unnoticed, and it meant that Webb and others needed to make constant reference to a dead president and a new frontier to keep NASA’s funding rolling in.

Going to the Moon made little sense, after all. It was criticised then and since as a monumental distraction from the problems of the Earth and a subsidy for the military-industrial complex – a white male fantasy in which fighter-pilot heroes ride rockets while the world looks on in awe. As the American poet Gil Scott-Heron put it in 1970: ‘No hot water, no toilets, no lights./(but Whitey’s on the moon)’. Yet Apollo was also one of the iconic moments of the 20th century, and inspired feelings of admiring wonder among millions of people that still resonate half a century later. It also encouraged many radical writers and activists to make connections between science, fiction and possibility that were substantially at odds with the political and financial interests key to driving the actual space programme. This sense of ambition for a revolutionary change – for something that the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch described as the ‘not-yet’ – is written across much of the previous century.

There are different versions of utopia, such as the Arcadian pastoral idyll or the unlimited consumption of Cockaigne, but the 20th century provided us with the most intensely technocratic versions of what a good future might look like. The cultural critic Constance Penley in 1997 called this ‘NASA/Trek’, an entanglement of technocratic managerialism with a Star Trek sense of quest and adventure. The sort of management imagined by Webb aimed to solve big problems with big money to stimulate innovation from universities and corporations alike. Although it required complex coordination, it was shot through with a sense of vision that brought together millions of people in a collective effort to achieve something that they could be proud of.

This future wasn’t that long ago, but it has felt lost. The Game of Thrones fantasies of Westeros distract us from the actual domination of capitalism by tech giants that use logistics and algorithms to deliver us all that we would ever need. Yet we need this radical future now more than ever.

The most worrying thing about this failure of imagination is that it is happening now, at a point when the entire human species, and lots of other ones too, are facing an Armageddon-sized climate crisis and a deadly pandemic. If everything was going well, we might be forgiven for being distracted by stories of heroes who never were and getting Five Guys Deliverooed to our front doors. It seems that, after a hard day at the app developers’ or the call centre, few people can conjure a new way of living.

Yet we have no choice. This carbon-intensive world can’t continue, and the collective development of real futures is more important now than ever. In 2015, a group of distinguished British scientists, economists and businessmen launched the Global Apollo Programme, calling on developed nations to commit to spending 0.02 per cent of their GDP, ever year for 10 years, to fund coordinated research to make carbon-free baseload electricity less costly than electricity from coal by the year 2025.

Meanwhile, Mariana Mazzucato, a professor in the economics of innovation and public value at University College London, used the Apollo space programme as an example of visionary collectivism in order to push forward her idea of ‘mission-oriented’ research and innovation at a multistate level. Her proposed missions are ambitious: gigantic attempts to conjoin governments, cities, business and citizens in achieving goals that will redefine the future for all of us. In her 2018 report to the European Commission she suggests a few: 100 carbon-neutral cities by 2030; a plastic-free ocean; addressing dementia. All these targets represent enormous challenges, requiring coordination between organisations and interest groups that are currently part of the problem. They also require that, in order to produce a future worth having, we stop doing most of the things we do now. (Tell that to the oil industry, routinely given to disguising business as usual with a promise that it has changed.)

Science-fiction writers have always had the sense that yesterday and tomorrow don’t need to be the same

Another version of this sort of response to grand challenges, one that directly inherits the Keynesian commitments of Webb’s space-age management, is the Green New Deal. Though the US and the UK versions are slightly different, both rely on the idea of massive state-backed intervention funding investments in renewable energy, retrofitting houses, reorganising our food production and so on. Vast sums of money and huge amounts of labour will be required to alter just about every area of human activity on the planet: so, imagine lifelike avatars that can have meetings in Los Angeles, vertical farming taking place in deep mines, entire cities being rebuilt to get rid of the need for the private car. This is the stuff of 1930s science fiction, the sort of realist speculation that projected change on a grand scale, but stayed away from magic and dragons.

The Apollo space programme, love it though I do, represents a past to which we can never return. It was based on military technologies and driven by imperial capitalism, and it guzzled gas like there was no tomorrow. Watching footage of Saturn V taking off always brings a tear to my grizzled eye, but that’s not sufficient reason to imagine that we could (or should) go back to then. But what I do want to rescue is the sense that the future can be different: the sense that science-fiction writers have always had that yesterday and tomorrow don’t need to be the same. Capitalism has captured the future, and is now commodifying it and selling it back to us as gizmos and widgets, or else distracting us with fantasy – defined by its refusal to engage in realism or real problems. As the literary critic Fredric Jameson said in 2003, or rather said that someone else said, ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.’

Now, more than ever, we need these stories about the future. Not the cityscape lensflare adverts in which we all have friends and lives that play to a soundtrack of Coldplay-lite thanks to our oh-so-very-smart telephones, and the sort of marketing taught in business schools. We need real futures, stories about radical changes that we’ll all be making in order to build the world differently. Deserts covered in solar panels, food made from algae grown in space, underground distribution systems that bring us what we need so that our roads can become parks for children to play in. These futures need to co-opt stories as compelling as those being told by Marvel and Samsung – not puritan warnings about what you can’t have, but pictures of lives that are rich and full, in which people can be heroes and you have nice things to eat.

This is the world that we need managery to make, and that we need wisdom, planning and complex organisation to produce. Webb would have relished the challenge, a way of organising that could produce something as sublime as an endless forest of wind turbines, or a train that travels as fast as a plane. It’s not too much to ask of clever monkeys like us, unless we continue to be distracted by Middle Earth and Instagram.