In September 1738, Benjamin Lay, a radical Quaker barely four feet tall, filled an animal bladder with bright red pokeberry juice, then tucked it into the secret compartment of a book. He donned a military uniform and a sword, covered himself in an overcoat, hid the book, and set off from his home in Abington, Pennsylvania for Burlington, New Jersey, where the Yearly Meeting of Philadelphia Quakers was being held, a gathering of the colony’s most powerful Quakers. Lay had a message for them.

Quakers have no formal ministers, so congregants speak as the spirit moves them. Lay was a man of large and unruly spirit. In a thundering voice that belied his stature, he announced that slaveholding was the greatest sin in the world. He threw off his overcoat to reveal his military uniform. The crowd gasped. He raised the book above his head, unsheathed his sword, and declared: ‘God will take vengeance on those who oppress their fellow creatures.’ He ran his sword through the book. The bladder exploded in a gush of blood, spattering the slaveholders sitting nearby. A group of Quaker men grabbed up Lay – he did not resist – and threw him out of the meeting house into the street. The soldier of God had delivered a chilling prophecy: slaveowning would destroy the Quaker faith.

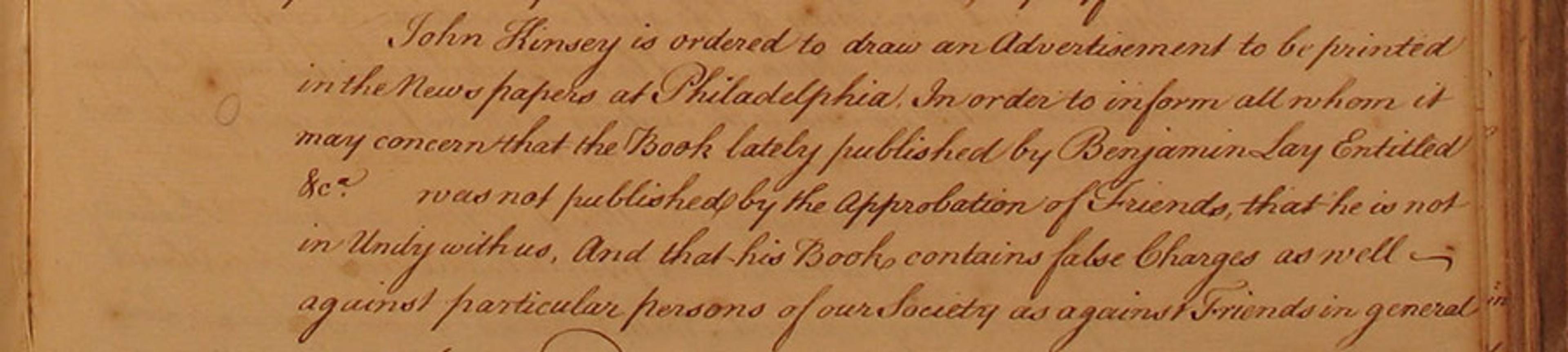

Extract from the minutes of the Yearly Meeting of Philadelphia Quakers, 1738, reads: ‘John Kinsey is ordered to draw an Advertisement to be printed in the Newspapers at Philadelphia, In order to inform all whom it may concern that the Book lately published by Benjamin Lay Entitled etc was not published by the Approbation of Friends, that he is not in Unity with us, And that his Book contains false Charges as well against particular persons of our Society as against Friends in general.’ Courtesy Friends Historical Library

Three weeks earlier, Lay had published his first and only book, All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. Here he detailed his struggle against wealthy and powerful Quaker slaveowners to abolish what he considered an evil institution. Two full generations before a robust anti-slavery movement would emerge in America and Great Britain in the 1780s, he demanded an immediate, uncompromising and unconditional end to slavery all around the world, joining his protest to the resistance of hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans in the New World, who were always the first abolitionists. Lay imagined not only an end to slavery, but a way of living outside the marketplace of capitalism, without violence to any living creature. He lived in a cave, made his own food and clothes, and practised vegetarianism. How did this man of common means and ordinary background arrive at the conclusion that slavery must be abolished at a time when so few others did? How did he break through to this very unusual position for his day and age? How did he become a revolutionary?

Lay’s radicalism can be thought of as a rope of four tightly braided strands. The first strand is a radical variant of Quakerism; this was the core of his very being. The second was seafaring, and the culture of the sea that he discovered during his working life as a sailor for a dozen years. Third was his direct contact with the enslaved people of Barbados in his time on that island during 1718-1720. Fourth was a kind of ‘commoning’ radicalism that he took up later in life, in the 1730s, based in part on his reading of ancient philosophy, especially the Cynic philosophers of Greece and Rome and their founder, Diogenes. These four strands combined to make Lay a determined radical who against all odds helped to forge the world’s first modern social movement: abolitionism.

Lay was born in 1682 in Copford, a village near Colchester in England; he was a third-generation Quaker. His grandfather and grandmother had joined the Quakers during their formative years, in 1655, and his parents followed in the faith. His father William was especially active. Like many children born to humble rural families in this sheep-farming and textile region, he worked as a shepherd. He loved the gentle hills of pastoral Essex and the animals he cared for there. It was, he later noted, the best work that a human being could do.

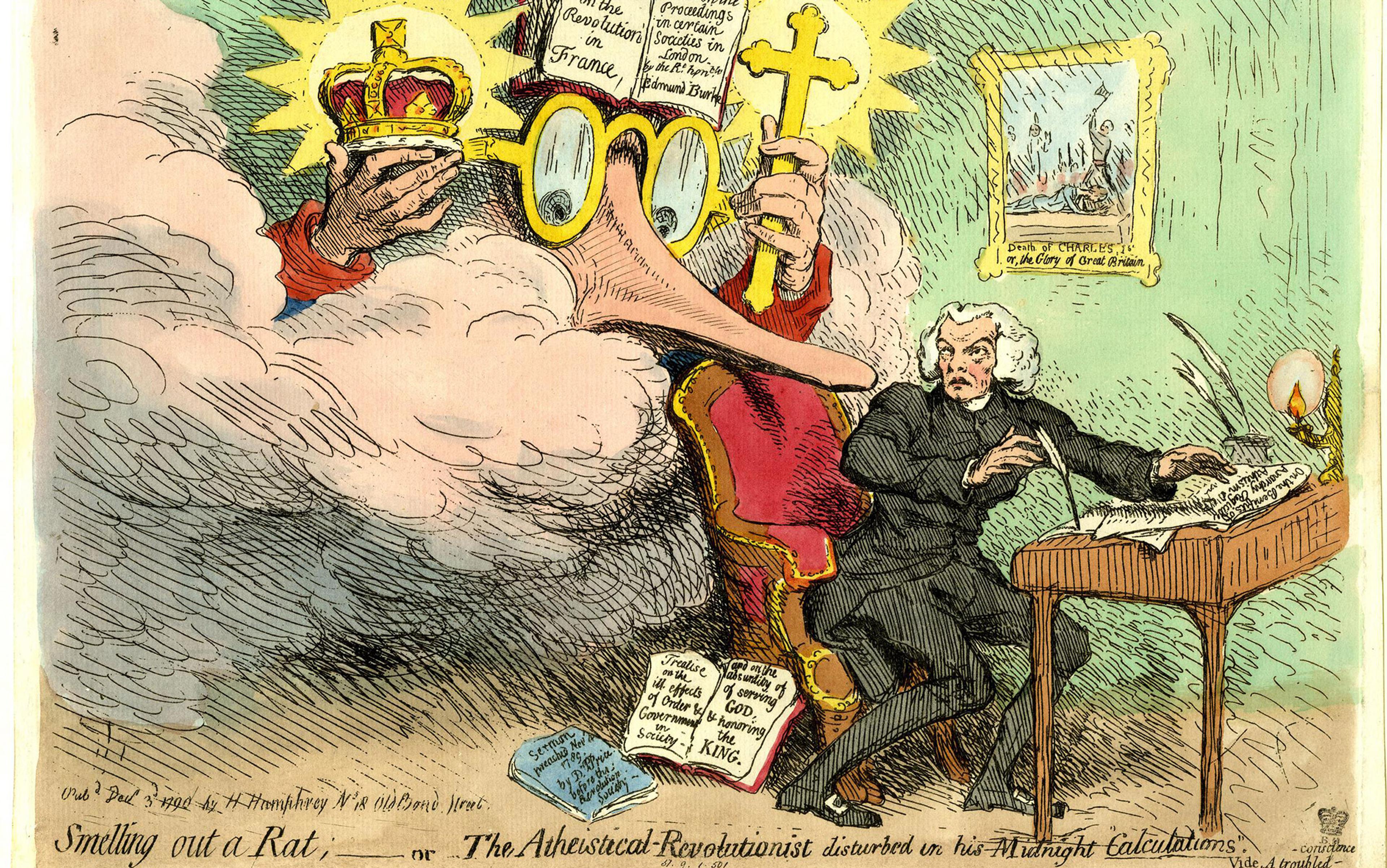

Even though Lay was born more than two decades after the conclusion of the English Civil War, that grand convulsion shaped his life in profound ways. As parliamentary forces led by Oliver Cromwell clashed with the royalist followers of King Charles I, censorship collapsed and radical Protestant groups such as the Levellers, Diggers, Ranters, Seekers and Quakers rushed into print proposing their own solutions to the problems of the day. They preached radical messages of equality and millenarianism, sometimes urging that the world itself be turned upside down. And they articulated democratic principles, arguing for their broad adoption throughout English society. Theirs were the first real critiques of slavery, which at the time was not yet fully racialised. These radicals attacked the press gang, the loss of the commons, forced labour, indentured servitude and African slavery. This was the bubbling cauldron of revolutionary thought from which Lay’s Quakerism was born, the first strand of his radicalism.

The early Quakers formed an intense and egalitarian religious community based on the notion of a shared ‘inward light’, the spark of divinity that resides in each and every person. Led by James Nayler and George Fox, the latter now remembered as the founding father of Quakerism, they challenged the class order of their times, insisting on spiritual equality, and subversively refusing to remove their hats to their so-called social superiors.

Benjamin Lay was a throwback to that early, radical phase of Quaker history

The more radical Nayler was the movement’s leading theologian, more sophisticated than Fox, and more given to direct action and elaborate street theatre, which became a Quaker staple. In 1656, Nayler reenacted the return of Jesus Christ to Jerusalem as women sang Hosannas and lay flowers in his path. Parliament saw this as an opportunity to get rid of a dangerously charismatic preacher who stirred up both religious and political resistance from below. They decided that his theatre constituted blasphemy and ordered that his forehead be branded with a ‘B’, his tongue be drilled through with a hot metal rod, and the flesh of his back be torn away by repeated floggings in both Bristol and London. Nayler never recovered from these vicious punishments, and died a broken man in 1660.

Years later, Lay carried on his tradition of radical street theatre. He also drew on the practice of John Perrot, who advised fellow Quakers not to take off their hats even when praying to God, who was, after all, within them; he was simply their equal.

In 1660, Charles II ascended to power, and England became a monarchy again. The pendulum swung the other way: censorship returned, and many Quakers were persecuted and banished. Fox responded by implementing a series of reforms in the Quaker community during the 1660s and ’70s that would root out the radicals, increase group cohesion, and turn a small revolutionary group into a robust, long-living Christian sect. Even though Lay was born 22 years later, he was a throwback to that early, radical phase of Quaker history. In some ways, he was the last radical of the English revolution as he channelled the militant ideas and practices of Nayler and Perrot throughout his revolutionary life.

The second strand of Lay’s radicalism took shape in 1703, when the 21-year-old was set to inherit his father’s farmstead in Copford. Ever the rebel, he turned his back on the farm and the animals that he loved, and set off for London – and from there for the high seas, where he became a sailor. His diminutive stature made him a valuable member of a ship’s crew: being smaller and more agile, he could do many things a sailor of average size could not do, such as scampering around in the top of the ship or getting into otherwise unreachable corners.

Lay lived on tall ships amid a motley crew for 12 years, and this is likely how he got his education, as literate sailors often taught their illiterate brothers how to read. He sailed around the world, and acquired a rich cosmopolitan experience and an initiation into a longstanding tradition of multi-ethnic radicalism at sea. He understood the fundamental truth of seafaring: every day, your life is in the hands of your fellow sailors. The occupation requires strict solidarity, regardless of who your fellow worker might be – brown, black or white; English Protestant or Irish Catholic. A common sailors’ phrase of the era was: ‘One and all, we are one and all together.’ Lay became a citizen of the world, and learned to transfer his seafaring solidarity to oppressed people around the globe.

He learned much about slavery through the stories of his fellow seamen. The sailor’s yarn was an important international means of communication. Sailors sat in a circle on the main deck, picking oakum and spinning yarns, knitting themselves together as a cohesive group as they told the stories of their lives, which for several included the horrors of slavery. A couple of Lay’s shipmates had been slaves themselves in Turkey or North Africa – this was not uncommon for European sailors who braved the waters of the Mediterranean. Other sailors had sailed on slavers, transporting human cargo from Africa to the Americas. What Lay remembered most vividly about these tales was the extreme violence committed against African women on the Middle Passage.

He related his seafaring experiences in his book All Slave-Keepers … Apostates, but tellingly he never talked about ‘race’, even though this idea and its associated practices were rapidly dividing up humanity at the very moment that he wrote. Throughout the Americas, slaveowners legislated slave codes to criminalise cooperation between black and white workers. Sensing the division inherent in the term, Lay used more neutral words to express human difference: ‘colour’, ‘nation’ and ‘people’. He refused the standard trope of the day to refer to Africans as ‘savage’ or ‘barbarian’; on the contrary, he reserved those descriptions for slavetraders and owners of European descent. Even more importantly, in his eyes, he used Biblical passages to resist the racial division of the world, emphasising Acts 17:26: God ‘made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth’. In other words, he said we are not different people; we are all the same people, deeply and divinely connected. This anti-racialising rhetoric reflected his experience at sea where he worked with a variety of people who were all ‘of one blood’. Maritime solidarity was the second strand in his rope.

The Lay home became a kind of meeting house for hundreds of enslaved people on Barbados

Lay ended his sailing days in 1718 when he decided to marry Sarah Smith, a Quaker from Deptford on the River Thames. She too was a little person. Lay had begun to quarrel with his fellow London Quakers, who were now under the sway of Fox’s reforms. With his wife, Lay left for Bridgetown, a bustling port city in what was then the world’s leading slave society – Barbados. There they opened up a little shop selling general merchandise on the waterfront. Lay would now see the workings of slavery with his own eyes. His contact with the brutality of the slave system and the struggles of Afro-Barbadian people produced the third strand in his rope of radicalism.

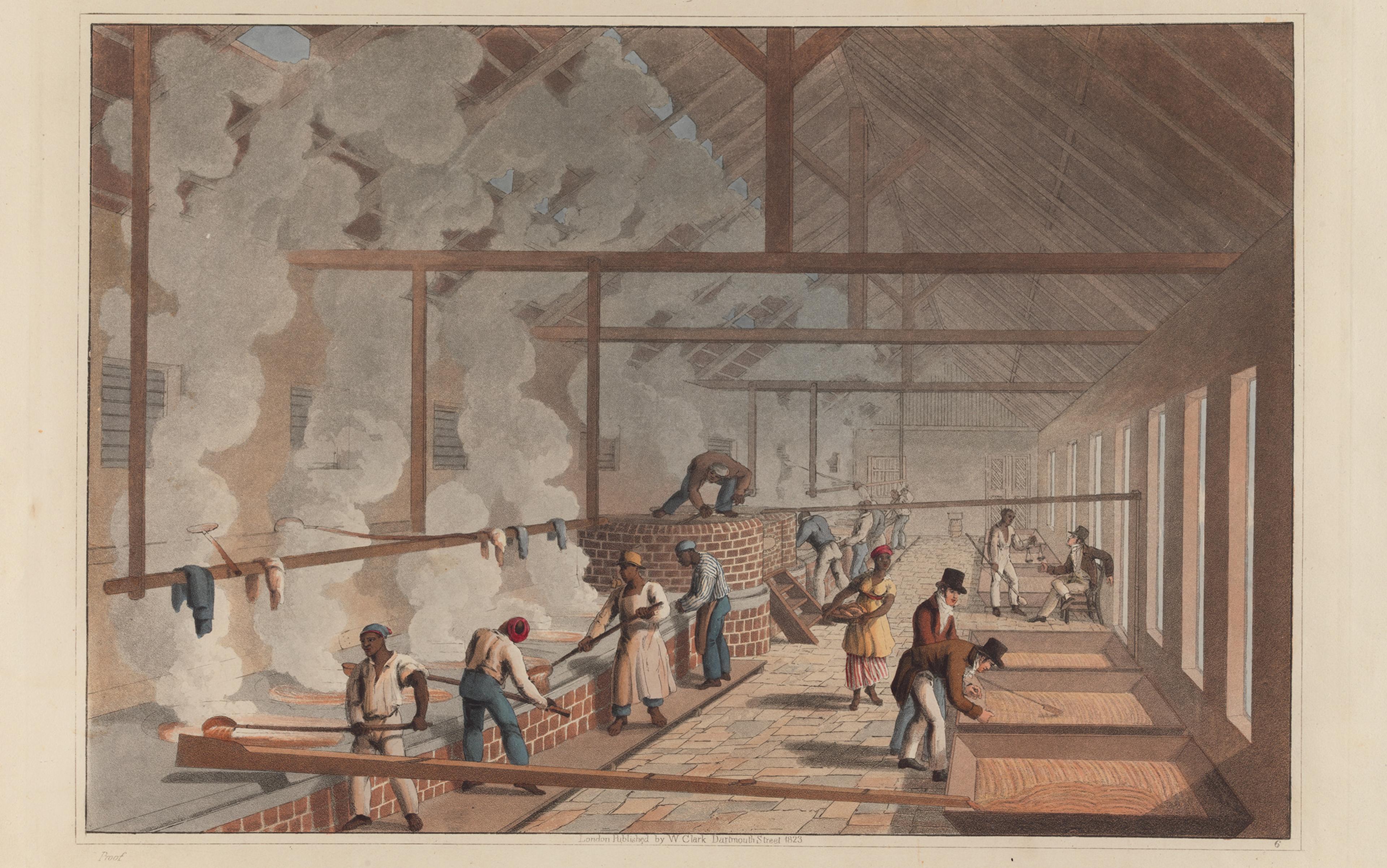

Lay watched in horror as enslaved people staggered into his shop and collapsed on the floor. Some actually died of overwork and hunger. He saw people being tortured, a common sight in Bridgetown. He saw grisly executions of slave rebels. He witnessed workers lose limbs to the machinery of the sugar factories. He got to know an enslaved cooper who committed suicide on a Sunday night, rather than endure the whippings his master administered every Monday morning. The tender-hearted Sarah was also affected by the pervasive atmosphere of violence. On her way to visit Quakers in Speightstown, 10 miles north of Bridgetown, she came upon an African man hanging by a chain, trembling as he was suspended above a pool of blood. She was struck dumb by the horror of the scene. Once she recovered, she went into the Quaker home where the slaveowners explained that the man had run away from the plantation and must now be taught a lesson for all of the enslaved to see. The Lays were deeply shaken by the cruelty they saw all around them.

They responded to the situation by feeding the hungry: they invited slaves to their home on Sundays, the day of rest, for meals and fellowship. Word of this kindness spread, and the Lay home became a kind of meeting house for hundreds of enslaved people, who not only partook of the food but listened to the couple denounce the slave system that was the source of their misery. The wealthy slaveowning master class of Barbados got wind of the meetings, and immediately applied pressure to the Lays to leave the island. Their anti-slavery ideas and even their basic human kindness made them enemies of the country. As the elite moved to banish them from Barbados, the Lays decided on their own to leave. Neither had the stomach to live among such violent depravity as all other whites on the island chose to do.

The couple returned to Colchester for a few years, and then left England for the last time. They sailed to Philadelphia in 1732. When Lay discovered slavery in the Quaker city of Philadelphia, where at the time about one in 11 was enslaved, and when he realised that many of these slaves were owned by wealthy Quakers, he flew into a rage. He redoubled his anti-slavery commitment and confronted Quaker slaveowners in meeting after meeting, eventually getting himself disowned from the Quaker community for the ardour and direct action of his protests, involving, as we saw above, the symbolic spattering of blood on the heads and bodies of slaveowners in 1738.

In All Slave-Keepers … Apostates, he spoke directly to Quaker merchants involved in the slave trade, charging them with the deaths of many innocent Africans. Warming to the fight, he added that, for all he knew, the merchants might have killed ‘many Hundreds of Thousands’. The contemporary Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database shows that in 1738, the very year that Lay wrote these words, more than 500,000 Africans had already died as a result of transoceanic slaving. Lay drew on his background in seafaring to denounce slavetraders as murderers. He was probably the first person to make a chilling allegation that would later be commonplace among abolitionists.

In Philadelphia and especially in the town of Abington, where the couple moved in 1734 (Sarah died only a year later), Lay not only carried out his militant actions against slaveowners, he added a final and distinctive strand to his rope of radicalism: he withdrew from the capitalist economy, adopted a radical lifestyle, and lived off the land as a commoner. In one sense, Lay returned to his rural roots in Copford, and in another he not only embraced but expanded the Quaker commitment to a simple, unpretentious life, the ‘plain style’ as it was called. He lived in a cave, grew his own food, and made his own clothes. His goal was to be a living example of equality with all living things, subsisting on ‘the innocent fruits of the earth’ – that is, without exploiting any human beings or animals. He refused complicity with any form of oppression.

To refuse sugar was to acknowledge that it was made with the blood of enslaved workers in the Caribbean

Lay was thus the first to articulate a modern politics of consumption. He boycotted all slave-produced commodities, which always disguised the horrific conditions under which they were produced. Anyone who dropped a cube of sugar into a cup of tea was thereby complicit with the sugar-planters of Barbados and the tea-plantation owners in East Asia, with their violent means of creating wealth. To refuse sugar, in turn, was to express solidarity with oppressed enslaved workers in the Caribbean, and to acknowledge that sugar was made with their blood. The modern global movement against sweatshops is based on the same idea.

An avid reader, Lay followed two writers on his path to commoning radicalism. He so dearly loved Thomas Tryon’s early argument for vegetarianism, A Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness (1683), that he carried the heavy tome with him on his travels. Tryon believed that war and violence grew from the way that human beings treated animals. Lay agreed. He saw the Quaker ‘inward light’ in all living creatures, and therefore thought it sinful to kill and eat them. His pacifist pantheism became a source of all ethics. He even refused to use wool for clothes as this would require the violent shearing of sheep. He therefore used flax, spinning it himself in his cave and making his own clothes of tow linen.

Lay also found antecedents and inspirations for his commoning radicalism in ancient philosophy, which he read avidly. Called a ‘Pythagorean-Christian-Cynic philosopher’ by Benjamin Franklin, Lay had a special interest in Diogenes, the founder of Cynic philosophy and a vegetarian who chose to live life in accordance with nature. Diogenes lived for a time in a pithos, a large jar used for storage, not unlike the small cave where Lay made his home. Both men conceived of philosophy as public action. Ideas must be acted out in visible, confrontational ways. Principles must be lived and expressed in everything one does. Lay also embraced the most fundamental idea of Cynicism: parrhesia or ‘speaking truth to power’. He repeated the Cynic saying: ‘The love of money is the root of all evil’ which had likely been spread among the early Christians by Cynic philosophers in the first place. Lay used Diogenes and other thinkers of antiquity to twist into place the last strand of his rope of radicalism, incorporating a militant, outspoken philosophy based on respect for nature.

In the end we must ask, why is Lay unknown to us? Most members of the general public have never heard of him. Historians are little better. Even specialists on abolition have rarely read his book. How did this happen to a man who must properly be regarded as a pioneer of abolitionism, the world’s first great social movement?

Quakers in the 18th century, led by their wealthy slaveowning elite, bear the original blame because of their unrelenting attacks on Lay. They denounced him, vilified him, and laughed at him. Worse, they cast him out, four times. He was probably the most disowned Quaker in the 18th century. His marginalisation began in his own lifetime.

Historians – including eminent historians of abolition – have also played a major part in erasing Lay from our historical memory. He never really fit the story they told about the abolitionist movement: ‘enlightened’ middle- and upper-class men arrived at the rational conclusion that slavery was wrong, and hence they abolished it. Lay was from the wrong class. He was not properly educated and therefore could not be considered enlightened. His ideas were too radical and his methods were too extreme. He must have been out of his mind. In The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1966), the renowned historian David Brion Davis called Lay a mentally deranged ‘little hunchback’, which draws attention to his dwarfism and disability. These too were causes of dismissal, when in fact they should have been seen as a source of empathy for others who made up the wretched of the Earth.

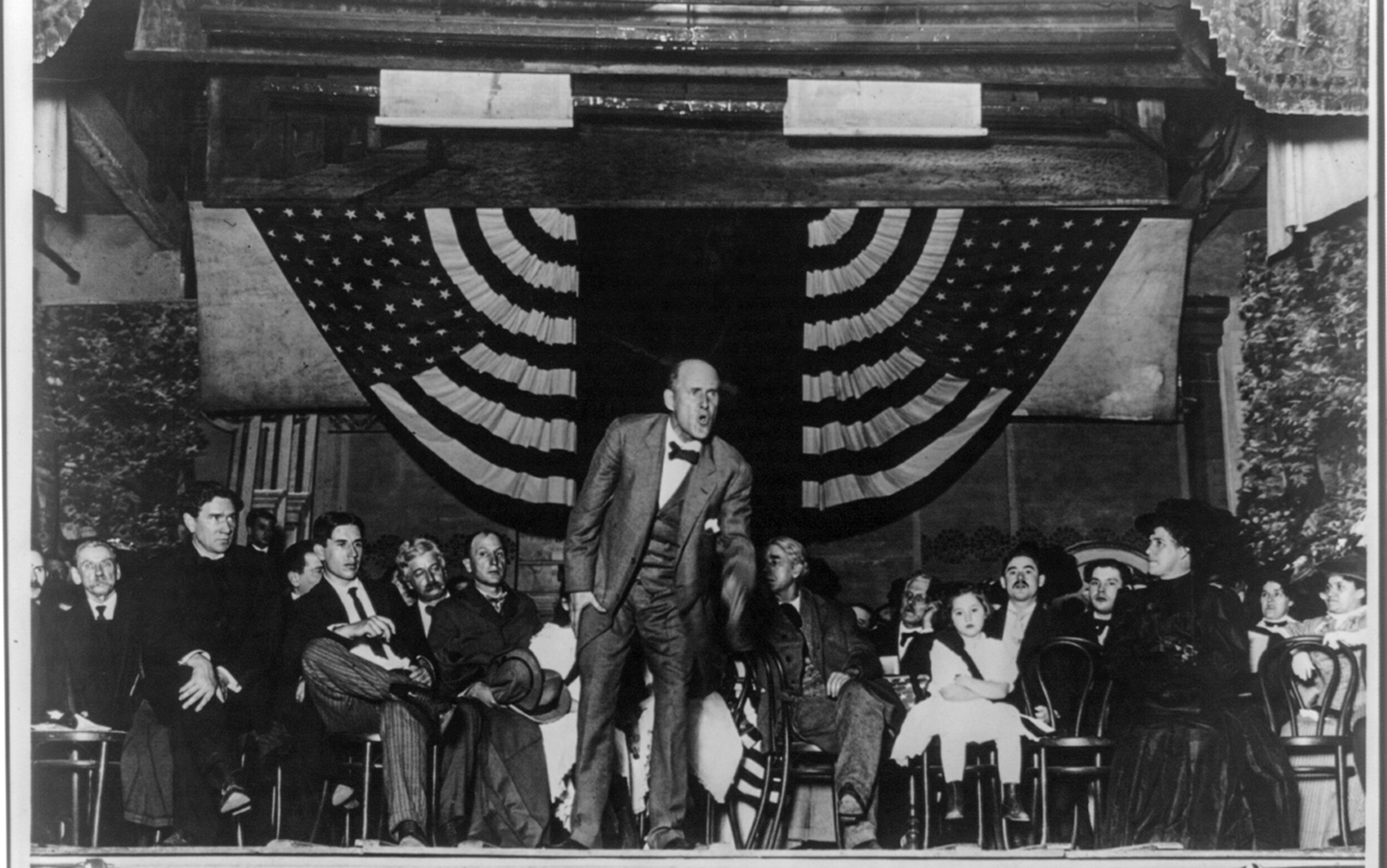

In the end, radical Quakerism, the solidarity of seafaring culture, firsthand knowledge of the struggles of enslaved people, a pantheistic commitment to animals and nature, all shaped by his understanding of subversive Greek philosophy, made Lay a revolutionary far ahead of his time. He deserves a central place in our history. As Americans debate who is a proper historical hero, Lay should be remembered as someone who, against all odds, stood for the highest and most humane ideals.

This article is a revised version of the remarks delivered at the James A Field, Jr Lecture in American History at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania on 11 October 2017. The author thanks Bruce Dorsey, Marjorie Murphy, Megan Brown and Timothy Burke for that wonderful occasion.