Starting in 1969, and for several years afterwards, in church basements and community centre kitchens in cities and towns around the United States, thousands of kids sat around a table every school day morning, eating hot breakfast served by the young adults of the Black Panther Party. At each seat there was a plate and utensil setting, a cup and a napkin. The children learned to use their fork and knife properly, eating eggs and grits and bacon and toast, washed down by juice or milk or hot chocolate – whatever local businesses had donated that week.

The Panthers – most of them in their late teens and early 20s, and about two-thirds of them women – had arrived at these community kitchens before dawn to prepare this hot meal for the children, serving them and then checking homework, and giving PE (political education) lessons.

‘Who invented the traffic light?’ a Panther would call out.

‘A Black man!’ the children responded.

They also learned that eating a filling breakfast was a right, and that a full belly helped them pay attention in school. The children – most but not all of whom were Black and Hispanic – were taught about Black and Hispanic inventors and artists and leaders, the stories that were (and still are) so often left out of mainstream histories. For many children, this was the first time they learned that a Black or other person of colour could be an engineer or a scientist or an artist.

The Panthers then taught the children to help clear their plates and pack their bags, and then walked them to school. In places where the Black Panther Party offered their Free Breakfast for Children Program, attendance rates and overall academic performance increased.

The Panthers’ breakfast programme addressed a dire need in communities around the country, but it and their other food justice programmes were always about more than feeding the hungry. They saw these ‘survival programmes’ – what the Panthers’ founders Bobby Seale and Huey P Newton called ‘survival pending revolution’ – as modelling their party’s socialist principles.

Courtesy the Washington Area Spark/Flickr

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded by Seale and Newton in Oakland, California in 1966, with an initial goal to address police brutality in the Black neighbourhoods of their city. Their name was inspired by a pamphlet for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in Alabama who used the imagery of a large, crouching black cat on their third-party ballots. The LCFO was begun by Stokely Carmichael, a leader in the civil rights organisation Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1965 to support Black candidates, and was dubbed ‘The Black Panther Party’ by the white media. The Panther had seemed an apt symbol: an animal who did not attack unless provoked, but who would then bravely defend itself.

Initially, Seale and Newton recruited young men who patrolled the streets with guns slung over their shoulders, often adopting a similar uniform of a black leather jacket and beret. If they saw an arrest in progress, they would stand nearby as witnesses to police actions and inform the arrestee of their rights, sometimes documenting the interaction with a camera. Unsurprisingly, local police were angered by the Panthers’ presence, and tension fomented.

The Panthers quickly moved beyond street patrols, addressing other needs of the community. One early effort sent members to direct traffic at a notoriously dangerous intersection, prompting the city to finally install a traffic light.

In the spring of 1967, the teenaged Tarika Lewis came to the Black Panther Party headquarters in Oakland and asked to join. She noted their own language in their Ten-Point Program supporting gender equality, and wanted to see women in their ranks. She later reflected: ‘When I joined the party, I was thrilled about becoming part of an organisation that believes in the equality of men and women …’ Lewis opened the door for many more women to join the party, both in Oakland, and among the quickly expanding chapters around the country. Lewis added: ‘One of the ironies of the Black Panther Party is that the images of the Black male with the jacket of a gun became emblematic but the reality is the majority of the rank-and-file members by the end of the ’60s are women.’

Each week more showed up, despite the propaganda telling parents the food was tainted

As they grew in number and neighbourhood influence, the Panthers wanted to better address local needs. They reached out to the SNCC for help in organising. The SNCC activist Curtis (Hayes) Muhammad said that the SNCC sent out members to teach the Panthers the approach they learned from their venerable leader Ella Baker: to enter a community and ask the people what they wanted and how to help. In Oakland, they found allies in Father Earl Neil and his parishioner Ruth Beckford, who gave them a space at the church and other resources, and support such as connecting them with parishioners and helping to prepare the space. From Beckford and Neil, the Panthers learned that local children often went to school hungry. The next step seemed clear.

The Panthers hosted their first Free Breakfast for Children Program at Father Neil’s St Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland on 20 January 1969. That first day, they served 11 kids. By the end of the week, more than 100 came. Each week more showed up, despite the propaganda campaign that law enforcement began, telling parents the food was tainted or threatening arrest for those who attended.

In early 1969, there were as many as 45 Black Panther Party chapters in cities and towns all over the country. By spring 1969, the party mandated all local chapters should host their own Free Breakfast for Children Program, and that all Panthers should work shifts supporting the programme. They shared their protocol, which included soliciting local businesses for food and cash donations to support the programme. Many businesses gave willingly. The help to the community was easy to see. Others needed a little nudging, such as boycotts outside the bodegas’ doors, informing potential customers that the proprietors refused to help hungry kids. These donations helped provide a hot breakfast cooked daily by the well-organised teams. Many of the party members arrived before dawn to prepare the food and set up the room. Others arrived a little later with a parade of children from local apartment buildings trailing behind them. The children were welcome to eat as much as they wanted.

The Black Panther’s Free Breakfast for Children Program is probably their best-known initiative, the press finding an intriguing story juxtaposing the Panther’s tough-guy-in-leather-jacket image with the act of serving small children plates of hot food. Importantly, it was mostly women who led these survival programmes, and women made up a majority of the Panther membership. They served in leadership roles from ‘Officer of the Day’ (essentially the office – and people – manager for each branch), to organising the many details of a location’s breakfast programme to initiating and leading food justice, healthcare and housing programmes within neighbourhoods. So why does the image of the Panthers as a masculinist and violent organisation persist? The answer lies in part with media distortion, influenced both by the sexism and racism that misrepresented the Panthers. There was also a misinformation campaign by the FBI, led by J Edgar Hoover, waged against the increasingly popular Panthers, which had an enduring impact on how people saw them.

The Black Panther Party had first made news headlines in 1966 and early 1967, with their neighbourhood patrols to counteract unjust arrests and rampant police brutality in Oakland. In these early days, when the most visible Panthers were armed men, news media was eager to share these provocative images alongside reporting that reinforced stereotypes of Black men as aggressive and dangerous. But from the beginning, Newton and Seale had articulated the party’s diverse goals in their Ten-Point Program, including an emphasis on education, employment and ‘land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace’. After a couple years of growth in party membership, the Panthers had begun to build programmes to address social problems. Then, over the next several years, it was women who took the reins of the programmes that became the focus of the Black Panther Party as it grew and evolved.

So much of the Panthers’ focus was on food justice programmes, in part because this was a way to immediately make a difference – people had to eat every day. But they also quickly found that food was integral to creating community, stoking agency and sharing culture. After Panthers held a food drive or helped take packages to elders up many flights of stairs, down would come a pot of rice and beans to share at the Panther office as a thank-you. The Panther Cleo Silvers would bring young teens in the neighbourhood to eat at inexpensive Indian, Chinese and Italian restaurants around New York City, wanting these young people to feel welcome in these spaces and experience diverse cuisines. ‘Sharing a meal was the best way to understand what people were thinking,’ Silvers said. ‘It’s the best way to really understand what’s important to them.’

The Panther women doing ‘women’s work’ was often taken for granted, and its legacies went uncelebrated

At the peak of their breakfast programme, the Panthers were feeding more kids around the country daily than the state of California did. The communities embraced them for this and their other survival programmes – which included helping secure safe housing, instituting door-to-door healthcare, developing innovative addiction treatment, free grocery distribution, clothes and shoes giveaways, as well as lending support to other local activist groups. This important work of the Panthers remains under-recognised.

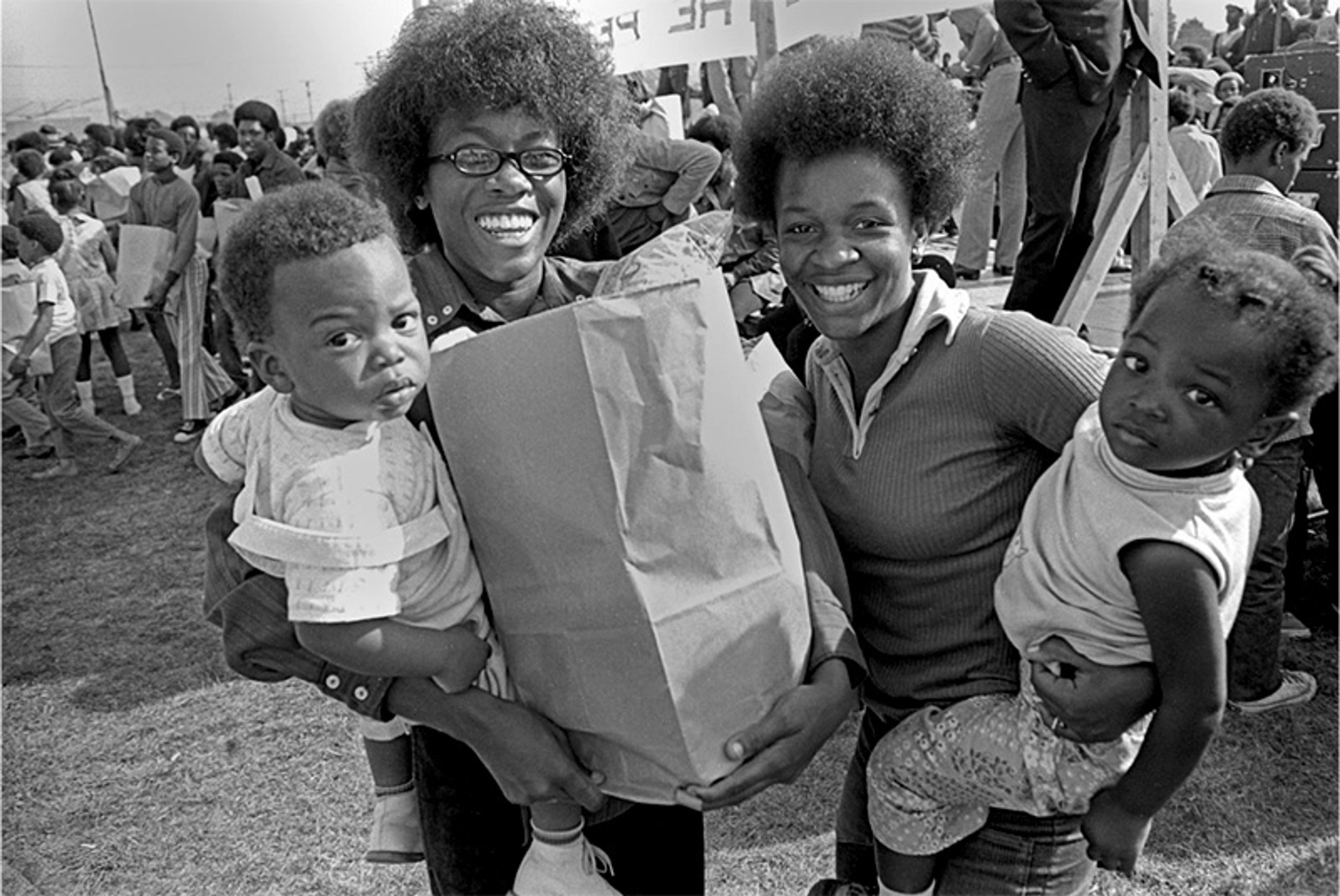

Free grocery distribution at the Black Community Survival Conference, 30 March 1972, Oakland, California. Photo © Bob Fitch Photography Archive/Stanford University Library

The historian Françoise N Hamlin of Brown University has used the term ‘activist mothering’ to help understand both the work that the women Panthers were doing – and as a reason why their leadership and accomplishments have escaped due recognition. Hamlin explains that they would develop ‘strategies particular to their communities by continuing (or expanding) work … [such as] the nurturing of youth …. from which she could maximise the return on her gendered social position.’ Feminised work is often expected of women, and is among the limited acceptable roles they can inhabit. The Panther women took on leadership roles in realms where they exert authority and expertise, and continued to expand the scope and influence of their work and voice within their community and beyond. But women doing ‘women’s work’ was often taken for granted, and its legacies went uncelebrated.

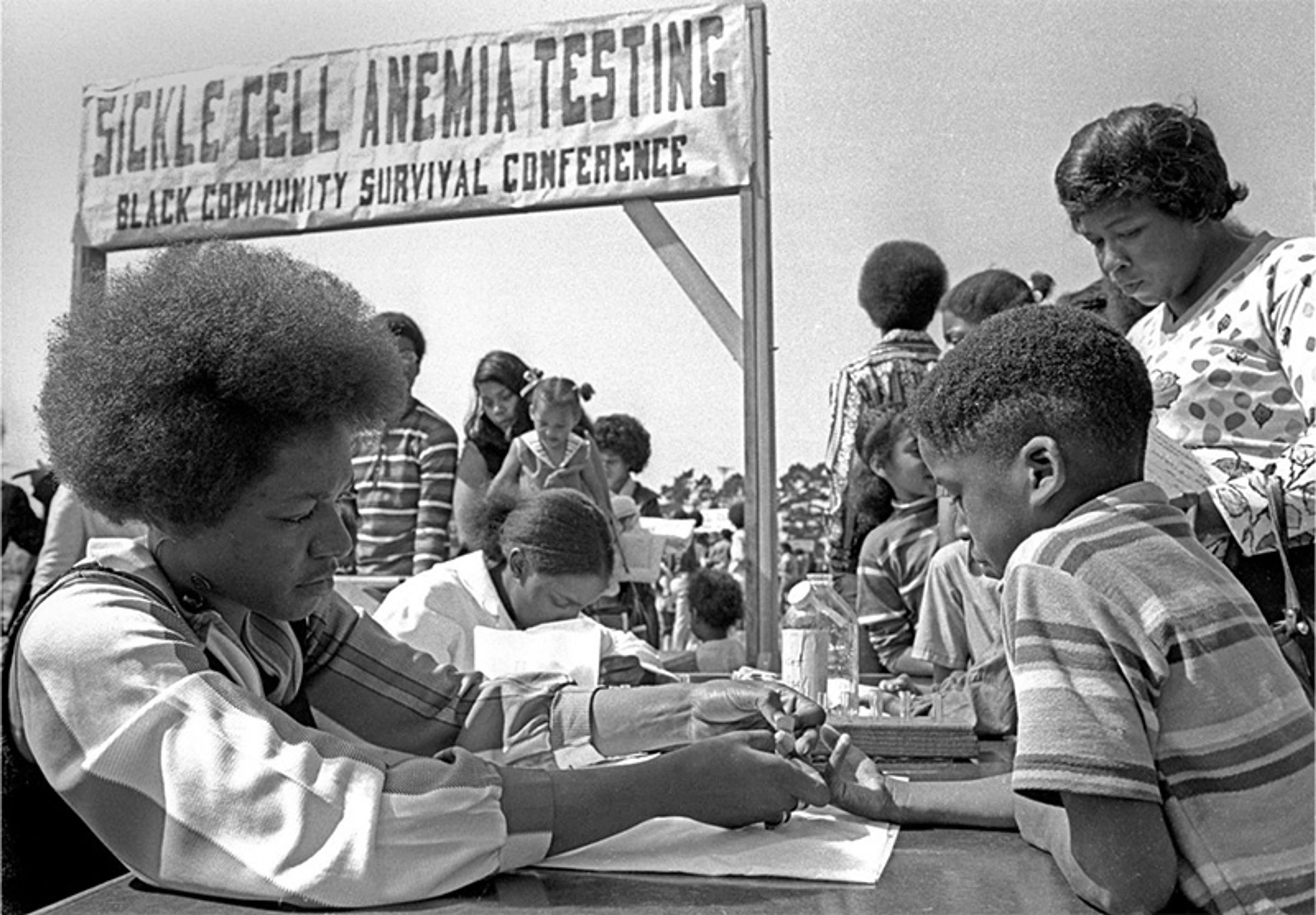

Testing for sickle cell anaemia at the Black Community Survival Conference, 30 March 1972, Oakland, California. Photo © Bob Fitch Photography Archive/Stanford University Library

These women may have been recognised, to a degree, within the communities they were working in, but they have long been under-appreciated. To many, seeing a woman feeding children or handing out clothes is not worth writing about or publishing photos of – but a tough young man doing the same upends expectations. When the Panthers’ Free Breakfast for Children Program did make mainstream news, the (almost always white male) reporters often focused on what they saw as this juxtaposition. But it was more than the reporters’ own biases perpetuating this inaccurate and enduring perception of the Panthers.

To reinforce the Panthers as violent and dangerous young men, the FBI also planted defamatory and untrue news stories with major news outlets. With their growing popularity, local and national law enforcement increasingly saw the Black Panther Party as a threat. In an internal classified memo written by Hoover – the FBI’s director and the mastermind of the massive illegal COINTELPRO (counter-intelligence programme) that sought to eliminate liberal-leaning and civil rights groups – he declared the Free Breakfast for Children Program ‘the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralise … the [Black Panther Party].’ Why was feeding hungry kids seen as so dangerous?

In many ways, it was food that helped the Black Panthers connect to the communities they sought to help. While the Panthers began their social work in Black and Hispanic communities, they soon came to seek to join with poor white communities too, in what the charismatic Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton called the Rainbow Coalition. More often than not, it was the women at the forefront of these initiatives, where they also learned: over breakfast, the children told them about a parent addicted to drugs or a home without food; when delivering bags of groceries to elders or families in need, they saw for themselves buildings without heat or with rats roaming underlit hallways. Informed by these experiences and conversations, the Panthers expanded their survival programmes and support of the community. They helped tenants organise and claim apartment buildings from delinquent landlords, they founded effective community-based addiction services, and cooperated with other groups who were fighting for healthier school lunches or better healthcare.

In feeding poor people, the Panther women stepped up to be the change they wanted and to advance the revolution for which they fought. Of course, the Panthers were not shy in educating the communities about their political leanings as they worked. It made so much sense that hungry kids deserved to eat; that the richest country in the world should ensure that no one was without food or a safe home. The future they envisioned – one in which the existing greedy leaders, as they taught and their weekly Panther Paper wrote about, were replaced by those serving the people – became not only visible but desirable to the long-oppressed communities they were helping with seemingly simple mutual aid and community-based solutions.

They demonstrated the need and benefit of a federal free breakfast programme

Hoover’s FBI and local law enforcement despised the Panthers, and the Panthers didn’t mince words either, coining the term ‘pigs’ named for the ‘fascists’ they saw as bringing drugs and violence into their communities. By late 1969, Hoover was waging an all-out war against the Panthers. Federal and local law enforcement agents were bent on destroying the Panthers’ free breakfast programme and what it represented. They confiscated food meant for poor children or destroyed it by soaking it with water or urinating on it; they spread lies about the breakfasts being poisoned, or the Panthers teaching hate and ‘anti-American’ rhetoric. And they ramped up their efforts, as Hoover himself wrote, to ‘neutralise … and destroy’ the Panthers themselves, through unfounded arrests and sometimes state-sanctioned assassinations. Among the casualties was Hampton, shot and killed while sleeping in his bed by Chicago cops who had concocted a story of a late-night firefight. While the truth is now more widely known – and was known even then to locals who were taken on tours of Hampton’s apartment, his blood-soaked mattress on display – there has been no official apology.

In the early 1970s, the Panthers’ national influence and, soon after, the breakfast programmes themselves, began to wane. One influence was the success of the FBI’s campaign against them, creating divisions among members and decreasing membership. There was also some internal tension about whether the Panthers should continue to work toward a complete dismantling of the existing political and economic system, as Newton and Seale had originally envisioned, or begin to create change through elected office and political influence. But even as these internal battles closed local chapters, some still found the benefits of the breakfast programme important enough to continue: around the country a few Panther chapters, such as the one in Seattle, even continued serving kids into the late 1970s.

In 1975, the federal government expanded their own free breakfast for school children programmes. The Panthers have only recently been recognised for demonstrating the need and benefit of a federal free breakfast programme – and there are still many programmes and initiatives they helped to create and that have been widely adopted but for which they are rarely given credit. Using the same community-centric enquiry that inspired the breakfast programme, the Panthers were able to identify health problems they saw afflicting these communities. The Panthers led the way in door-to-door healthcare, lead-paint legislation and remediation, sickle cell anaemia research and treatment, acupuncture protocol for addiction treatment, and even wrote the Patient’s Bill of Rights. This has resulted in a national awareness around the negative effects of lead paint that has helped many, mostly children from low-income families; and the addiction protocol they helped popularise is used around the world. Many of these initiatives are still seen as both effective and progressive, but few know the role the Panthers played in their development.

It began with food. As the Panther and healthcare activist Cleo Silvers points out, so much of community care is connected to food. Healthy food is necessary for ‘having a healthy body’, Silvers says, but also ‘a healthy attitude … And that all comes from relationships with people and sharing.’ The Panthers knew that food was the conduit to the community, a direct line to public health, and a means to model a more just community. Imagine what they could have accomplished if their efforts were supported and not destroyed.