In a play published in 1662, a playwright imagined a bizarre educational set-up for women. In a ‘female academy’ (also the name of the play), young women of ‘honourable Birth’ and ‘ancient descent’ are cloistered within a house. Separated from the outside world – and with only old matrons to keep them company – they are bordered by two grates, windows into the open air that are barred over. The women are available to be looked at and listened to, but not to touch or be touched. On one side, throngs of men stand around just to see them. By the other grate, women gather in groups to listen to their educated discourse.

It’s an odd set-up, similar, in a way, to that of the medieval anchoress, enclosed from the world outside and largely forbidden from speaking to men, or anyone, beyond their walls. And, like the anchoresses of old, these women dedicated themselves to reading and learning, discussing everything from women’s capacity for wit, to the nature of truth. The men who stand around outside are capable of discussing only one thing: their ‘minds are so full of thoughts of the Female Sex’, so they ‘have no room for any other subject.’ Of course.

What is going on in this play? Is it an image of idealised female intellectual development? Maybe, but there’s a spanner in the works: the women being educated then use their eloquence to claim that women are incapable of wisdom, and that it is nigh-on impossible for a woman to acquit herself in public. Is it then a work of misogyny, crafted by some 17th-century woman-hating wit? Hardly. The women are concerned with bettering themselves, of learning everything they can, and the men they fend off appear to be irredeemably stupid.

Could it be a model of a real educational setting; the type of schooling enjoyed by its author? The answer is, alas, still no. By the mid-17th century, the idea of a formal women’s education was beginning to spread – in the summer of 1673, a school in Tottenham, north of London, advertised its ability to educate ‘gentlewomen’ – but, in the 1620s, when the play’s author was born, there was no such luck. Women of a certain social class learnt only the feminine essentials: how to sew, dance, and ‘prattle’.

With its imagined world, and irreconcilable contradictions, The Female Academy is a good window into thinking about its author, Margaret Cavendish (1623-73): the poet, philosopher, scientist, playwright, fashion pioneer, science fiction writer and early feminist (her job titles could go on and on). Cavendish lived through a violent Civil War, published her poetry, prose and drama under her own name when to do so was all but unheard of for a woman, and became something of an early modern celebrity. She flits across pages and pages of sources from the period, from Samuel Pepys’s scandalised diary entries (in one entry, he huffs that ‘All the town-talk is now-a-days of her extravagancies’) to letters about court gossip. In the four centuries after her birth, approaches to her vacillate between idolising her appearance and performances (John Evelyn, the 17th-century diarist, must have angered his wife when he wrote repeatedly in his diary of how he could not stay away from Cavendish’s ‘extraordinary fanciful habit, garb, and discourse’), and being rather less adoring. Virginia Woolf let the full force of her insults fly at Cavendish, calling her ‘crack-brained and bird-witted’, a ‘giant cucumber’, and a ‘bogey to frighten clever girls with’. As late as 1979, a literary study argued that Cavendish’s writing was evidence of her ‘schizophrenia’.

Was Cavendish a feminist pioneer, or an eccentric dilettante? Early scientist, or ‘mad Madge’? And why, exactly, do opinions insist on varying between such poles?

Born Margaret Lucas in 1623, her early life and education bear an odd resemblance to the women she imagined in The Female Academy, yet not in the way that we might expect. She had no thorough education at the hands of ‘grave matrons’ – no expectation to discourse on philosophical subjects, or even to express herself well – but was, instead, instructed as the perfect daughter of the wealthy, well-connected but not aristocratic classes. She learnt how to dance, and how to sing. What else could a woman need?

Her education was, however, like her imagined women in one way. It was a life of extreme seclusion. In the large country house of St John’s Abbey in Colchester – built on former monastic land that had said farewell to its religious community after England’s Reformation – Margaret was curiously isolated. As the youngest child of a large family, she spent hours and hours alone. Her father had died shortly after her birth, and her mother was a model of sheltered widowhood, keeping herself and her family away from the society of Essex that surrounded them. Many of Margaret’s elder brothers and sisters had already grown up and married. She was, for long stretches of her childhood, almost completely alone. She turned to imagined worlds for her company, filling pages and pages of her ‘baby-books’ with her sprawling, spidery handwriting. The siblings she did have around – a sister, at points – filled her with nothing but anxiety: she would listen for hours outside her door, just checking to see if she could still hear her breathing.

Margaret’s mother and perhaps Margaret herself were paraded through town before being imprisoned

Before long, Margaret’s childhood anxiety would seem not neurotic nor out of place but tragically prescient. By the summer of 1642, it was clear that England was about to collapse into serious civil disturbance, if not all-out civil war. The 11 years of Charles I’s personal rule – the period in which the king had governed alone after the short-lived parliaments of 1628 and the escalating criticism of his policies – had come to an end in 1640. The king had been obliged to call the Short Parliament (so called because it lasted only three weeks) to try to fund the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland, wars that had begun after he had attempted to reform the Church north of the border. The Short Parliament was followed by the Long Parliament in the same year; Charles’s years of reigning alone were over. And, soon, his years of ruling at all would draw to a close: after an ill-fated attempt to arrest some particularly rebellious MPs in January 1642, the king was forced to retreat into exile as the skirmishes continued around him. Skirmishes became battles, and battles became wars and, in 1649, the king would be executed.

In this period of disruption and divided loyalties, the Lucas family pinned their colours to the mast. They were devout Royalists – supporters of Charles I – and in a growingly Puritan Colchester, this was a problem. By August 1642, Margaret’s brother John had begun to make preparations to send horses and weapons to the king. The people of Colchester noticed, and stormed the house. Everything was ransacked, furniture and bedding stolen, the family vault opened and the coffins stabbed through with swords. The women in the house – Margaret’s mother, and perhaps Margaret herself – were paraded through the town before being imprisoned in the jail. It was terrifying, dramatic and momentous, but it soon became unremarkable: a similar rampage was repeated not even six years later. This time, the marauding forces cut the hair off Margaret’s recently deceased mother to wear as a wig.

In 1653, Londoners could wind their way over to the churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral, which was less a space of divine contemplation than a bustling marketplace for vendors, many of them selling books just fresh from the printers. In among this chaos of crowded shops and stalls was the bookshop of the esteemed publishing duo John Martin and James Allestree. Under the papery piles of their works (religious tracts, scientific pamphlets, political writings) was something quite unusual. Sitting in large folio format was a book with the title Poems and Fancies. Upon opening, the reader would be greeted with everything from rhyming couplets on the nature of atoms, to verses on the existence of fairies.

One section of these poems was a little different to the others, however. Away from the worlds of theory and imagination, some of the poems stayed closer to home. Just a few years after the fighting of the Civil War had stopped, one of the poems returned to the battlefield, describing the bodies of the soldiers left behind:

Some, their legs hang dangling by the nervous strings,

And shoulders cut, hung loose, like flying wings.

Here heads are cleft in two parts, brains lie mashed,

And all their faces into slices hashed.

The poet, Margaret Cavendish, may not have seen much of the battlefield up close, but she had seen the ravages of the Civil War reach her own house. After the disorder of the early skirmishes had forced its way into her childhood, she had entered the fray fully. She left her family – and her life of secluded writing – to become one of Queen Henrietta Maria’s ladies-in-waiting. Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I, was living at Oxford with the exiled Royalists after months of riding around the country attempting to ensure the delivery of weapons to them.

Cavendish hated court. She had left her quiet life for one of endless chatter but no more interest. She detested the hours of gossip, sitting and waiting, and more gossip. She had no privacy, no time to retire or write. Years later, when she was reunited with her pen, she would write a play about her experience at court called The Presence. Her own character, ‘Lady Bashful’, speaks no words on stage.

Terrifying sea journeys (and unfortunate female travellers) became a motif of Cavendish’s later writings

Within the pages of Poems and Fancies, there are more clues about how Cavendish’s life took shape as the Civil War rumbled on. In one poem, she likens a ‘young Lady’ to a ship sent into the ‘world’s sea’. Everything appears to be going well – ‘with winds of praise and beauty’s flowing tide’ – before disaster strikes. Storms hit the boat (‘rebellious clouds foul black’), and the ship is pushed off-course, away from happiness and prosperity and into the ‘troubled seas of misery’.

In the summer of 1644, Cavendish’s journey away from her home and her family would take her much further than Oxford. As one of her ladies-in-waiting, she had no choice but to follow Queen Henrietta Maria when she decided to leave England. This was no easy choice. Heavily pregnant, and aware that her Oxford base was less secure as the Royalist forces suffered heavy losses in the north, the queen was extremely vulnerable. One parliamentarian general, the Earl of Essex, had devised a plan to exploit the Royalist weakness and intended to capture her and, in so doing, force a quicker end to the war. For her own safety and the safety of the Royalist cause, Henrietta Maria had to leave her husband (she would never see him again) and make plans to cross the Channel to France, her native country and where she still had family at court. She gave birth away from home, left her baby in the arms of a friend, and fled to the port in disguise. Once on board the ship, parliamentarian forces fired upon her. The queen upped the stakes: she instructed the captain that, if it seemed like the boat was about to be captured, he was to blow up the ship instead. They escaped, but it is no surprise that terrifying sea journeys (and unfortunate female travellers) became a motif of Cavendish’s later writings.

But, if Poems and Fancies provides a semi-biographical gloss to Cavendish’s life – there are elegies for her brothers who died in the war, and a poem for her dead mother – how did it come to be published in 1653, in Cromwell’s London, when Cavendish herself had left for exile some nine years ago? And how did Cavendish come to have a book published at all? In the 17th century, works by women reaching the printing press were vanishingly few and far between. Between 1621 and 1625, only eight works by women were published, an estimated 0.5 per cent of all books printed in the period. Between 1651 to 1655 – the years in which Cavendish published four volumes – 59 new works by women appeared; an estimated 1.3 per cent of total publications. Even with this uptick in women’s writing, the vast majority of these works by women were on the ‘safe’ subjects of maternal advice or religion. Women who didn’t stay within these boundaries risked more than just not being read; they could be branded as improper, as scandalous, as somehow promiscuous for baring their words to the page. Cavendish was a trend-setter, and an outlier.

Once again, there’s a clue as to how this happened in Cavendish’s more personal writing. Towards the end of her collection, she describes a bride covered in jewels and gold meeting a bridegroom ‘dressed by honours fine’. The emphasis on the opulent finery might have been a poetic embellishment, but the marriage was not: in 1644 in Paris, Margaret married William Cavendish, then a marquis and later to become the first Duke of Newcastle. Despite his title and his fame – he had been a Royalist commander at the ill-fated Battle of Marston Moor, which caused his exile – the pair married in relative penury. The war had taken everything from them. What it couldn’t take, though, was their minds. Prior to the war, William had been an intellectual patron – a friend of everyone from the philosopher Thomas Hobbes to the playwright Ben Jonson. During his exile, he still circulated with the philosophers René Descartes and Pierre Gassendi (on one occasion, Margaret even sat at dinner with both men). In marrying William, Margaret was marrying a world of educational opportunities, and a man with the connections – and social strength – to make publication possible.

Lord Cavendish with His Wife Margaret in the Garden of Rubens in Antwerp (1662) by Gonzales Coques. Courtesy Wikipedia

Margaret and William spent the duration of Cromwell’s Protectorate ensconced in Europe, in a house previously owned by the painter Peter Paul Rubens. They were continually hard up. William’s family lands were seized by the government and Margaret’s own had been run to ruin. But she continued to write, and to think. After her first book was published in 1653, she had written 10 more by 1666. In 1660, she returned to England with her husband. With Cromwell dead – and his body exhumed and posthumously beheaded – the country was safe for Royalists again.

Cavendish is normally remembered for three things: for being ‘mad’ (an accusation that has dogged her since an all-too-easily scandalised reader of her first book, one Dorothy Osborne, quipped that she had seen ‘soberer people in Bedlam’), for wearing outrageous clothes (she supposedly cavorted around London in a carriage pulled by eight white bulls, and wore dresses cut to below the level of her nipples), and, rather more nebulously, for being the ‘mother of science fiction’.

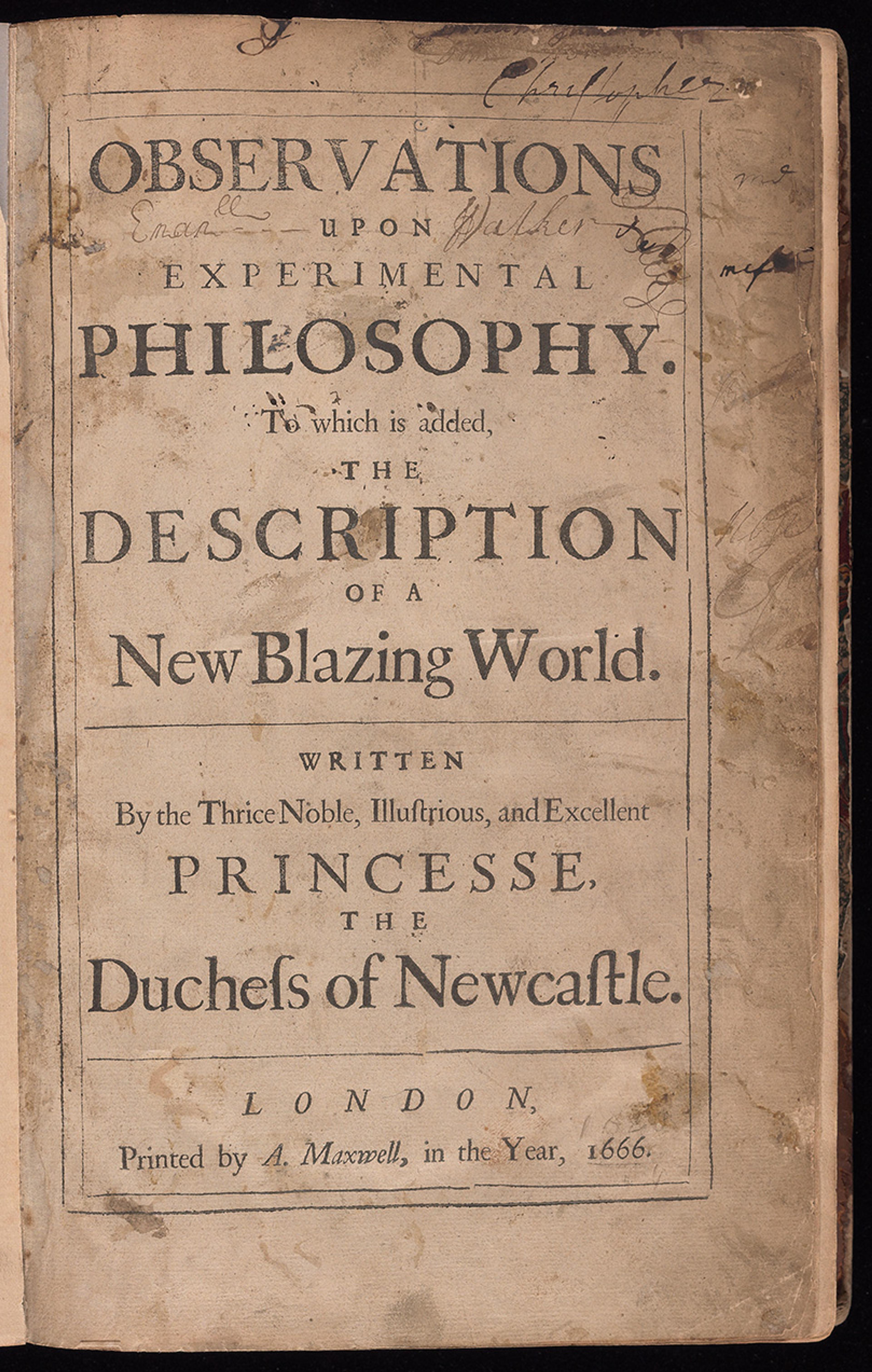

Printed in London in 1666. Courtesy the Beinecke Library, Yale University

What does this last designation mean? Science fiction is often thought to be a contemporary genre born out of industrialism, inventions and powerful machines. But Cavendish’s book The Blazing World (1666) – with its futuristic submarines in a parallel world, races of anthropomorphic human-animals, and flashy scientific experiments – is indeed an early work of science fiction.

She railed against the assumptions and presumptions of the men of the Royal Society

In many ways, the book is a perfect summation of her ideas and her influence. The novel opens with a young girl gathering seashells on a beach when she is suddenly captured by a merchant. Just as he thinks he is the ‘happiest man of the world’, an almighty storm hits the boat, and whirls it out of control and into the North Pole. The marauding merchant and his seamen die quickly in the extreme temperatures, but the girl is kept alive by the ‘light of her beauty’ and the ‘heat of her youth’. She survives as the boat travels into a new world where she is greeted by animal-human hybrids – lice-men, bear-men, fox-men – and gets married to the emperor. As empress of this world, she sets about trying to explain and investigate the land under her domain, from the hot deserts to the cold ice; from the largest animals down to the smallest. The method she chooses for these investigations is, of course, science. She gives all her subjects a role: the bear-men are her experimental philosophers, the bird-men her astronomers, and the lice-men her mathematicians: they all work beneath her, and the rest of the book is a romp of descriptions of philosophical experiments, with microscopes and mathematical explanations, scientific debates and explorations of sapphic love. Here, Cavendish was again radical: her explorations of lesbianism – in her plays, and in The Blazing World – are unusual for the 17th century. Rather than being the bawdy, sticky imaginations of men, her description of women’s relationships bears the hallmarks of truth and emotion. ‘But why may not I love a Woman with the same affection I could a Man?’ asks one of her characters in The Convent of Pleasure (1668).

The Blazing World is one of the earliest novels, a work of science fiction, and the first book to imagine a whole new world. It’s also one of Cavendish’s philosophical and scientific texts, engaging with debates over experimentation and reason that were raging in the period. When it was first published in 1666, it was appended to her Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy – perhaps Cavendish’s most fiery work of natural philosophy, in which she railed against the assumptions and presumptions of the men of the Royal Society who claimed that everything could be discovered, and known, through the new frontiers of scientific experimentation. In our modern age, where the scientific method is so closely tied to empiricism, it can be hard to take Cavendish’s qualms over experiments seriously. But she was writing and thinking in an age that had seen the disruption wrought by the utopian ideals of the Puritans during the Civil War. Her scientific beliefs – anti-utopian; more insistent on internal reason than external proof; and sceptical of claims to absolute, unbounded knowledge – are deeply political.

The Blazing World is also a feminist work – if we are not squeamish about using that term to include historical writing that considers women’s place in society, and the strictures they live under. A young girl is made empress of the whole world, she is rescued from terror (naturally, for Cavendish, a disastrous shipwreck) and then sets about furthering herself intellectually. It is no coincidence that directing all this cerebral endeavour is a woman.

What does Cavendish tell us about now? How is this woman from the 17th century relevant? With her boldness and her bravery in writing, Cavendish seems like a woman so out of her time, so much closer to our own. And, when taken out of her context, she can be used as a figure to reflect so many issues: women’s education, the denigration of women’s writing, the difficulty of being taken seriously. Cavendish could, with little difficulty, become something of a feminist poster-girl; a woman so different to all the others of her period.

But there is another question. Isn’t she somehow reprehensible? She was a devout Royalist, after all – a conservative, who upheld ideas about a rigid, hierarchical social order that firmly put aristocrats (and monarchs) at the top, and everyone else on a descending scale. Cavendish saw no contradiction between this and her radicalism elsewhere. For every moment of her ‘right-on’ writing is a moment of something rather trickier. Is Cavendish too regressive, to awful, to be paid attention to now?

She also points to a lost history: words that never met with the ink of a printing press

I’d like to suggest something beyond either of these possibilities. From The Blazing World to her countless other works that speak to women’s place in 17th-century society – plays about women retreating from the society of men; letters about the unbearable humiliation of childbirth – it becomes clear that Cavendish was not, truly, an outlier. Her writing may be a part of a small percentage that was published, but she was tied to a much broader tradition of women’s writing about women, about how their sex seemed to be subject to separate rules than for men.

In the British Library, there is a manuscript of the 15th-century French-Italian poet Christine de Pizan. De Pizan wrote The Book of the City of Ladies which imagines a city where women could be safe from men to pursue their own aims. On the title page is a doodle. There’s a chance it was done by Cavendish herself: she and William owned this exact copy. Cavendish is connected, too, to reams of other little-known women’s writing, from the letters of women in her circle about the struggles of child mortality, to the poems and plays written by her stepdaughters during the Civil War. Rather than just reflecting today’s debates about women and women’s writing, she also points to a lost history: words that never met with the ink of a printing press, unlike her own successes.

Cavendish died in 1673, after publishing no fewer than 23 volumes. She achieved the unthinkable, in many ways. She published, she wrote, she thought about everything – from theories of matter to the nature of queens. She was taken seriously by some, and less seriously by others; she is revered in some circles now, and still denigrated in others. And it’s her contradictions that give her story life – her slippery, brilliant difficulty – alongside her connection to a whole blazing world of women’s words. Her epitaph in Westminster Abbey still speaks for her: she was a ‘wise wittie & learned Lady, which her many Bookes do well testifie’.