On 10 June 2008, Dick Fuld, the soon-to-be infamous CEO of a soon-to-be infamous investment bank, Lehman Brothers in New York, assembled his executive committee in response to a second-quarter earnings report registering nearly $3 billion in losses. The purpose of the meeting was for everybody in Fuld’s inner circle to weigh in on a single question. The question was not: ‘How do we restructure the company in order to spin off our most toxic assets?’ Nor was it: ‘How can we increase our liquidity to address ballooning debts?’ Nor even: ‘With whom could we merge if it becomes necessary to avoid bankruptcy?’ All these questions would be asked with increasing urgency during the coming weeks. But, as far as Fuld was concerned, the more pressing question was: ‘How do we restore confidence?’

If, like me, you happen to be a masochistic consumer of post-mortems of the subprime-mortgage crisis that climaxed nearly a decade ago, you will regularly encounter variations of this anecdote, often with little further commentary – since confidence is among the most common and least interrogated terms in finance and economics. When I first read Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big to Fail (2009) shortly after publication, I fixated upon this passage because I was simultaneously working on a Masters thesis about Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man (1857). Like Melville, I had begun obsessively cataloguing the diverse contexts in which the word confidence was invoked; the tortured ambiguities created by those invocations; and the ways in which confidence’s often contradictory connotations could be used to confuse and deceive. As the scene from the Lehman Brothers boardroom all too clearly demonstrates, we often skip past the question of what confidence is, to ask how it can be manipulated.

To Fuld, confidence was the endgame of a hypothetical publicity campaign designed to persuade the rest of the world to accept his version of reality. It became commonplace to characterise Fuld as a delusional recluse, who sabotaged Lehman’s chance to get ‘bailed out’ like every other US investment bank by stubbornly refusing to admit how desperate the situation had become. This is how James Woods plays him in the 2011 TV adaptation of Sorkin’s book. But the villainisation of a few powerful individuals in the aftermath of a crisis is a common way we avoid reckoning with a more troubling conclusion: there might be systemic flaws in the structure of our financial system.

Fuld’s plan to solve Lehman’s problems by carefully massaging public perception was not the product of crackpot magical thinking, but the conventional wisdom of the profession. He was right to insist that any difference between Lehman’s exposure to toxic mortgage-backed securities and the exposure of their competitors was marginal. It was the disproportionate amount of media attention that distinguished Lehman from the rest of the industry. Such coverage was, in Fuld’s opinion, orchestrated by hedge-fund managers such as David Einhorn who, by short-selling Lehman’s stock, positioned themselves to profit from public panic surrounding the bank. Lehman was being persecuted for misdemeanours afflicting every bank.

While Fuld was likely right that ‘hedgies’ had suppressed Lehman’s stock price with smear campaigns, his own team used analogous tactics to prop it up. The largest single-day gain in the company’s history came on 18 March 2008, following a highly publicised quarterly earnings report. Erin Callan, who delivered the report via conference call to more than 10,000 investors and journalists, remembers realising that ‘the fate of Lehman Brothers might hang in the balance’. As with Einhorn’s speeches, Callan’s statement revealed little that wasn’t a matter of public record. Rather, subjective aspects of her demeanour – her easy tone, the casual way she handled pressing questions, her ability, in short, to disguise her awareness of what was at stake – were what interested the analysts. ‘If I could communicate the facts clearly and confidently, we would be fine,’ she recalls thinking: ‘The idea that my voice and my words were so important to these multitudes was mind-boggling.’

Such episodes explain why Fuld, in the ensuing months, doubled down on the strategy to ‘restore confidence’, repeatedly calling upon the most attractive, charismatic member of his management team to feign optimism in the face of skeptical reporters and, whenever possible, cable news cameras. Callan describes herself as ‘a star, young female performer’ who realised too late that she’d been given a ‘role’ that required her to ‘Just tell the story. Communicate the message. That’s it.’ Lehman’s calculated publicity barrage presented her as one of the most powerful women on Wall Street and the face of the company. It also made her a ‘lightning rod for Lehman criticism’, so that, as things grew more desperate, one of Fuld’s final attempts to build confidence involved having her theatrically ‘fired’ (in fact, she resigned).

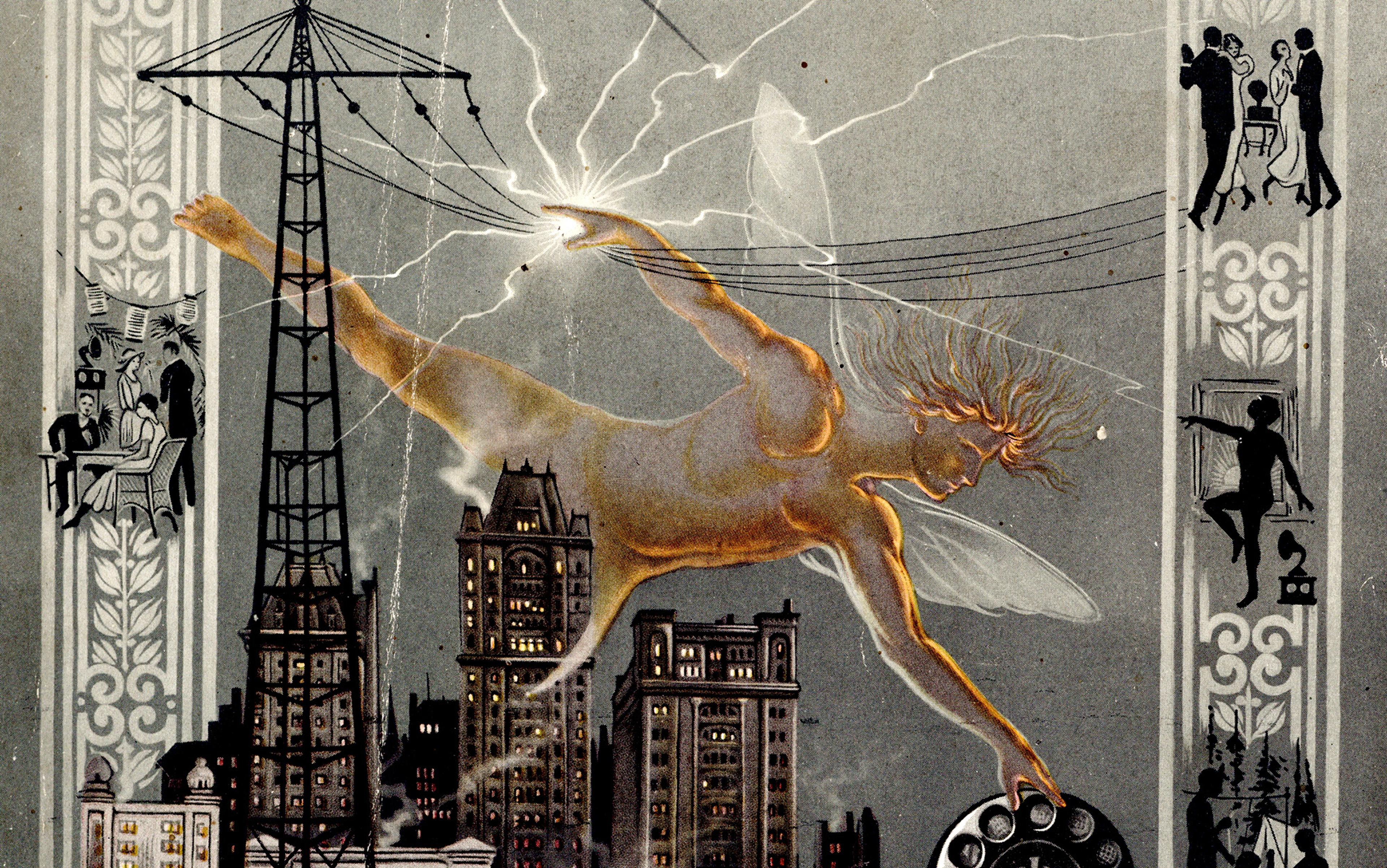

Finance is theatre. Both require the collective voluntary suspension of disbelief. When we buy stocks, or even so much as make a bank deposit, we implicate ourselves in the illusion that a few slips of paper, a few drops of ink or a few lines of code are interchangeable with bushels of wheat, parcels of land and weeks of labour. Pretending that the Prince of Denmark speaks in English verse, or that French police inspectors sing harmony, is a petty achievement of collective imagination compared with currencies and securities.

At the theatre, in exchange for our suspension of disbelief, we expect a concerted effort to produce verisimilitude. The narrative we preemptively consent to must be absorbing and at least minimally plausible. Efforts must be made to disguise the cables protruding from Spider-Man’s costume. Comanche warriors shouldn’t be played by dudes from Appalachia. The demand for verisimilitude is what makes theatre risky. The audience reserves the right to stop pretending whenever they feel their feats of imagination are not being earned. They could decide at any moment that jeering the actors or hurling rotten tomatoes is superior entertainment. No matter how tight the script, no matter how well-rehearsed the cast or expensive the production, there is still always a chance that it all goes terribly wrong.

Finance requires, in moments of crisis, the production of confidence in others by those who have none themselves

Confidence is finance’s fourth wall. It is held up on one side by the convenience of money – and the public’s passion for that convenience, which persuades them to trade their labour and property for greenbacks and bitcoins. It is held up on the other side by the producers of money, who naturally benefit from the public’s passion for what they produce, but who must sustain the agreeable but ultimately fantastical illusion that money has any intrinsic value in the face of daily reminders that it does not. The financial system depends upon the plausibility of narratives of wealth and commerce performed by those best positioned to know those narratives are facile, if not frankly false.

Finance requires, particularly in moments of crisis, the production of confidence in others by those who have none themselves. The normalisation of this deception is justified by a reasonable fear of the unknown. If the multitudes suddenly agreed that the financial system, global in scale and ever more interwoven in our daily lives, is not worthy of their confidence, what would be the result? It strains the imagination. From Karl Marx to John Maynard Keynes political economists believed that a wholesale rejection of the prevailing system of exchange would look an awful lot like revolution – with all the associated violence and suffering. What institutions or, for that matter, governments would survive a lifting of the veil over the theatre of global finance? And with what would they be replaced?

Perhaps it is preferable to be lulled by the pleasant fictions of scrolling stock quotes, S&P ratings and Fortune magazine rankings. But how long can confidence be sustained if there is widespread acceptance of the truth that a huge proportion of the financial wealth supposedly ‘circulating’ through the global economy is purely theoretical, reproducing itself automatically, such that increasingly small proportions of it ever exist as anything more than digital signals bouncing off satellites between Bloomberg terminals and tax havens? The paper millionaire graduates to pixel billionaire without sharpening a needle, shipping a widget or creating a job.

According to John Maynard Keynes, economists habitually ignored or downplayed the centrality of confidence to market activity because it contradicted the profession’s conventional models of economic behaviour, which assume that agents consistently make choices based on rational self-interest. Such models offer the illusion that uncertainty is calculable (a calculation that is, coincidently, often called a confidence interval) and that risk can be reliably managed. Keynes told a colleague in 1938: ‘Generally speaking, in making a decision we have before us a large number of alternatives, none of which is demonstrably more “rational” than the others.’ Instead, Keynes said, reiterating a point he made in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936): ‘we fall back … on motives of another kind, which are not “rational” in the sense of being concerned with the evaluation of consequences, but are decided by habit, instinct, preference, desire, will, etc.’

Keynes believed that if businesses actually obeyed the prescriptions for rational behaviour upon which orthodox economic models are based, nobody would ever build, buy, barter or bankroll anything. The human propensities towards hope, faith, even reckless gambling, have far greater effects upon enterprise than estimations of potential profit, which, in most cases, prove comically inaccurate. ‘A large proportion of our positive activities depend upon spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation,’ Keynes wrote. And if that optimism falters, ‘leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die’. The automation of capitalist accumulation is economic apocalypse.

For Keynes, the ‘state of confidence’ involves ‘assuming that the existing state of affairs will continue indefinitely’ even though ‘we know from extensive experience that this is most unlikely’. Confidence is what makes you continue to bet on black, even when you know you will inevitably see red. It spurs an irrational appetite for risk-taking. The ‘state of confidence’ aggregates many highly subjective and often only semi-conscious projections of the future. It is an amorphous variable, impossible to quantify or reliably account for, but liable to be the determining factor in the success of any investment decision, since abrupt and unpredictable shifts in the state of confidence can unsettle any sector of the economy, or even the economy as a whole, almost instantaneously.

What fascinates me about this enigma at the centre of economics is that it is called confidence. It stands, simultaneously, as a synonym for certainty and uncertainty; and, I’d argue, every invocation of confidence, in economics, politics or literature, should be read with this paradox in mind. Proclamations of confidence are frequently used as substitutes for substantive action and healthy self-reflection by financiers such as Fuld, who are incapable of disinterestedly evaluating any alternative to the outcomes they ask others to be confident in. Their expertise relies on access to supposedly more, and better, information but in any given moment that information can be made irrelevant by public opinion. As the actions of Lehman executives testify, the experts know this, which creates an incentives problem, since managing public confidence with misinformation might be more effective than taking substantive action based on proprietary knowledge. This explains why the characters in Melville’s novel have been conditioned to believe that, merely by asking for confidence, you admit you don’t deserve it.

Confidence becomes an essential consideration because prices respond to even the smallest changes in perception

Keynes acknowledges the term’s peculiar malleability by regularly placing its technical and colloquial invocations in close proximity. He wants to make clear that confidence cannot be quantified, reliably controlled, or pinned down with equations. Econometrics, he insists, is blind to the ‘animal spirits’. It would seem that Keynes’s contribution to this discussion is mainly to confuse it and confound his successors who, on this matter, have elected mostly to ignore him. But Keynes does clarify how the disruptive effects of swings in the state of confidence are magnified in economies dominated by large, concentrated financial centres – as was the case in the US in 1929, or 2008, or now. The volatility of the US economy, which has been rocked by financial crisis with disconcerting regularity since the founding of the New York Stock Exchange, is directly attributable to the taste, and talent, in the US for securitisation and speculation. As Keynes put it: ‘Americans are apt to be unduly interested in discovering what average opinion believes average opinion to be; and this national weakness find its nemesis in the stock market.’

Confidence enters macroeconomics through the Stock Exchange. ‘In the absence of securities markets,’ Keynes explained, ‘there is no object in frequently attempting to revalue an investment to which we are committed.’ The farmer cannot ‘remove his capital from the farming business’ on a whim, then ‘reconsider whether he should return to it later in the week’. Before securities trading was common practice, the farmer’s confidence, the shipper’s confidence and the realtor’s confidence had no impact on the simple supply-and-demand logic that set the prices for their goods. ‘But the Stock Exchange revalues many investments every day, and the revaluations give a frequent opportunity to the individual … to revise his commitments.’

At the Exchange, one can buy corn, even when corn is not in season, or a stake in a building, even when no tenants are moving in or out. Securities can be invented, amalgamated, contracted or split. Under the pressure of constant negotiation, confidence becomes an essential consideration because prices respond to even the smallest changes in perception, changes that can be based on reliable information, compelling narratives or abject rumours about specific companies, whole industries or the entire economy. When corporations are motivated by and reliant upon stockholders, small changes in the state of confidence towards a single company can produce butterfly effects through the whole economy.

Eighty years before Keynes published The General Theory, Melville stated plainly: ‘Confidence is the indispensable basis of all sorts of business transactions. Without it, commerce between man and man, as between country and country, would, like a watch, run down and stop.’ The Confidence-Man was equal parts experimental fiction, political economy and prophecy. Via a series of loosely connected vignettes set aboard a Mississippi steamboat, Melville, at the height of his powers, demonstrated how confidence could be made to mean everything and nothing. It could lubricate the gears of commerce or grind them to a halt; sweep up the individual in the ‘cosmopolitan and confident tide’ of ‘that multiform pilgrim species, man’ or leave him ‘in the dark’ with nothing but his own doubts, and possibly the devil, for company.

The novel drove Melville to the brink of madness. Upon its completion, he told his friend, the fellow American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, that he had ‘made up his mind to be annihilated’, and he abandoned his craft. The author of Moby-Dick lived another 34 years, but never published another novel. He contracted the crisis of confidence that his novel was designed to discourage and, soon thereafter, so did the nation. Six months later, Melville’s publisher was bankrupted in the Panic of 1857, and its warehouse burned to the ground with the unsold copies of his novel inside. For close to a century, almost nobody read it.

The Confidence-Man was inspired by ‘the original confidence man’ – a charismatic larcenist who was arrested and tried several times between 1849 and 1857. His exploits, which would, vicariously, inspire films such as The Sting (1973) and American Hustle (2013), were fodder for the mass-market newspapers of antebellum America, especially the most popular daily in the nation, The New York Herald. The ‘original confidence man’ would be arrested for a series of petty crimes under a series of pseudonyms, but the press permanently associated him with the epithet coined by the Herald in connection with the swindle that first brought him public attention. Operating under the name of William Thompson, he would gregariously strike up conversations with strangers in Manhattan’s public parks and railway stations, and, after some deliberation, turn to the subject of ‘man’s lack of confidence in his fellow man’. If his new acquaintance defended the magnanimity of mankind, Thompson would ask, as a demonstration of that faith, to borrow his watch or his wallet, with which he would, of course, abscond.

In numerous scenes, Melville attempts to reproduce dialogue that might climax in a request for a ‘demonstration of confidence’. The ‘confidence man’ and his ‘confidence trick’, along with their derivatives (confidence game, conman, con, con-artist, etc) had, by 1857, become part of a native parlance of deception that flourishes in popular culture to this day. This legacy was secured not because there was anything exceptional about ‘the original confidence man’, but rather because the owner and editor of the Herald, James Gordon Bennett, recognised the conman did more than quench his readers’ thirst for true-crime stories: it was an archetype that could be productively co-opted into his own personal polemics against rival publishers, corrupt politicians and, especially, financial speculators, all of whom, according to Bennett, profited – like conmen – by preying on the goodwill and gullibility of honest citizens. By turning the conman into one of his trademark editorial tropes, Bennett endowed confidence with the pejorative sense it retains to this day. In Bennett’s wildly popular paper, confidence was associated with deception, conspiracy and crass self-interest, as much as with faith, trust and assurance.

Bennett’s perversion of confidence’s connotations was quite deliberate. He appropriated the confidence-man figure for an express purpose: to make his readers wary of Wall Street. Bennett’s ‘Money Market’ column was a staple of the Herald from the beginning of its run in 1835. Regardless of how pressing his obligations were as owner, editor and primary correspondent of the Herald, Bennett made daily visits to the financial district, so that he could offer ‘a legitimate and exact record of what is honestly done in Wall Street, and an exposure … of what is dishonestly done there’. Other financial columnists, he claimed, were satisfied to be ‘accessory to the swindling of the sharpers … who trade on public credulity to abuse public confidence’. By contrast, the Herald would ‘unravel with impartiality and justice the various shades and webs of speculative fraud – and credit – and currency and humbugs’.

For Bennett, the implications of confidence were never far removed from the market. He had witnessed how an alliance of prominent bankers, led by Nicholas Biddle of the Bank of the United States, had deliberately produced the Panic of 1837 to pressure the US president Martin Van Buren to reinstate the federal charter that had been revoked by his predecessor, Andrew Jackson. He’d seen how, as the crisis deepened beyond what anyone had predicted, the competing factions pleaded with each other and with the general public to ‘restore confidence’ – exactly the phrase Fuld would deploy two centuries later. But while Biddle and Van Buren tried, as Bennett put it, to ‘outbid each other for the confidence of their community’, Bennett used the ascendant power of his ‘penny paper’ to ‘destroy confidence’.

Mass media and organised finance, both emerging out of lower Manhattan, were increasingly codependent

In his opinion, a speculative bubble had been popped, and the more painful it was for the bankers and brokers who had inflated it, the better off the nation would be in the long run. On the front page of the Herald, at the peak of the panic, Bennett reported that:

Wall Street, and its business neighbourhood, from river to river, has been for a week in a terrible convulsion. The banks – the merchants – the brokers – the speculators, have been rolling onward together in one undistinguishable mass, down the stream of bankruptcy and ruin.

He predicted that the ‘disruption of confidence in commerce’ would spread ‘like a fire in the mountains, into the elevations of political life’, producing ‘disaster and confusion every where’. Far from bracing his readers for the ramifications of the panic on employment, wages and inflation, he wrote in no uncertain terms ‘we rejoice at it’, and assured them that ‘all the old questions of the day are gone for ever – broken to atoms’. He promised to increase the Herald’s print run by 40 per cent to serve public demand for ‘a fuller, more accurate, more scientific, and more independent history of the present GREAT REVULSION OF 1837’.

Bennett’s coverage of the Panic of 1837 hastened the rise of the Herald. The insider knowledge and idiosyncratic interpretation he brought to the crisis made him peculiarly situated, 12 years later, to appreciate a character whose calls for confidence served an unambiguously criminal enterprise. Within days of the original confidence man’s arrest, Bennett published his editorial ‘The Confidence Man on a Large Scale’, in which he described the con-man as a ‘financial genius’ and ‘a distinguished operator’ from the active business of ‘the street’. Had he practised his ‘genius’ only a few blocks north, on Wall Street, he could have ‘retired to a life of virtuous ease, the possessor of a clear conscience, and one million of dollars’. It is the speculator and the stockbroker, Bennett argued, who are most ‘occupied by this process of “confidence”’, and who are therefore the ‘real’ confidence-men.

As the 1850s unfolded, amid rising sectional tension, Bennett fastened this distinctive derogatory epithet, confidence man, to a multitude of criminals, both petty and white-collar, as well as to public figures of whom he disapproved – including rival editors, financial magnates, political powerbrokers and presidential candidates. The con became a central trope in Bennett’s columns, which reached hundreds of thousands of readers daily.

When you read the Herald (to which Melville subscribed), it becomes clear that The Confidence-Man is, to no small extent, a commentary on its persuasive power and the dangers of Bennett’s paranoid style. Melville depicts a shamelessly self-obsessed citizenry, infected with cynicism and paralysed by the fear of being duped. He satirises Bennett’s eagerness to destroy that confidence which is ‘the indispensable basis’ of capitalist democracy. Melville’s novel hints at what even Keynes was slow to realise: that mass media and organised finance, emerging more or less simultaneously out of lower Manhattan, were increasingly codependent. This codependence increased the US economy’s vulnerability to crises of confidence.

Melville, Biddle, Callan and Fuld are all purveyors of what I call the rhetoric of confidence. They hope, by allaying the fears of the masses, to protect their investments or perhaps, more altruistically, the interests of their community, from volatile swings in the state of confidence. Consider, for instance, this passage from Francis Blair, editor of the Washington Globe, who begged Bennett to cease his agitation during the Panic of 1837:

Every man must see that the remedy for this disastrous state of things is a restoration of confidence … All that is necessary to enable sound men and sound banking institutions to resume their regular and useful business is confidence. Confidence would produce forbearance; forbearance would give time; time would bring round the circle of seasonable crops, and the returns of manufacturing industry, and allow opportunity for the influence of saving economy; and another year would open with reviving hope, invigorated energy, directed by a chastened and more cautious enterprise.

But while the rhetoric of confidence is usually deployed optimistically – to stave off imminent crisis or alleviate the effects of a crisis that is already unfolding – it is important to recognise that figures such as Bennett and Einhorn also use it to ‘destroy confidence’, believing that sustaining an overinflated state of confidence will make the eventual crash only more catastrophic.

Bennett and Blair both intuited, as did several other Jacksonian publishers and politicians who had witnessed the rapid development of securities markets and mass media in the preceding two decades, that Wall Street made the US economy unstable, in part because it was so sensitive to public confidence. They also recognised that their publications, which could reach unprecedented proportions of the populace, had a potentially outsized influence on the state of confidence. The factors that affect the state of confidence are, as Keynes showed, multitudinous. They can be unexpected: for instance, widespread belt-tightening after a natural disaster or terrorist attack – and even imperceptible – rumours, innuendo and grassroots paranoia, the only historical record of which might be the crisis itself. But, if there is a means by which the state of confidence can be materialised and manipulated, it is mass media.

The increasing centrality of finance to the US economy in recent decades, just as during Melville’s lifetime, coincides with an explosion of accessible, inexpensive publications. Following Keynes’s logic, I do not view this as a coincidence. The greater the proportion of macroeconomic activity that depends on securitisation, the more the volatility (incumbent to securities markets) permeates the larger economy. Under these conditions, any person or institution with the capacity to persuade the populace to alter their economic behaviour has the power to radically unsettle the marketplace. The stock market does not necessarily cause apprehension. It measures it. The market becomes as strong or weak as it is reported to be.

Should, in 2008, Bear, Lehman and the rest have been bailed out? In 2018, would there even be time to?

When Fuld proposed a publicity barrage with the intention of ‘restoring confidence’ in Lehman Brothers, he was conceding that a persuasive fiction, widely disseminated via the media, could relieve the firm of pressures from creditors, regulators, analysts, hedge funds and investors more effectively than substantive strategies to reorganise and raise liquidity. A century and a half earlier, Melville had recognised confidence as a shorthand for the emerging codependence of finance and mass media in antebellum America. That codependence has grown more integral as finance has come to account for an ever-increasing proportion of economic activity. The industry now has a litany of publications, broadcast networks, applications and other media dedicated solely to its promotion. And major media outlets are interwoven with finance through both their public coverage and their private operations.

As we consume more media (and more personalised media), fluctuations in the state of confidence are likely to be even more extreme. The highest highs will be sustained by financial news outlets whose sources and audience are substantially identical, reinforcing the conventional wisdom as it recycles it ad nauseam. And the crashes will be both deeper and more sudden. You might remember the spectacle of ubiquitous Blackberry PDAs simultaneously registering and inciting panic as the Bear Stearns share price tanked during the climactic scene of The Big Short (2015). Ten years later, that scene still captures herd mentality, but in slow motion. The bankers and brokers clogging the aisles of the auditorium would now trade the price down to zero from their seats – if they hadn’t already automated their portfolios to sell. Contemporary media technology has made possible an eradication of financial wealth via mass panic so total and immediate it could not generate enough suspense to satisfy Hollywood producers. It remains debatable whether, in 2008, the US Treasury and Federal Reserve should have stepped in to bail out Bear, Lehman and the rest. In 2018, would they even have time to?

The forgotten lesson of Keynes’s General Theory is that movements of metrics such as securities indexes, interest rates and GDP – presented in periods of stability as the very substance of the economy (Wow! Look at the Dow!) – are really only symptoms of the ‘animal spirits’ and, especially, their expressions. Levels of consumption, investment and employment depend on the contagion of ‘spontaneous optimism’. While it remains hard to predict how individuals will interpret ‘what average opinion believes average opinion to be’, we can be certain that those interpretations will be disproportionately driven by viral media. Studying television trends, political messaging, pop music, internet memes, video games, advertising, bestsellers, social-media influencers, core curriculums and demographics is now as productive an approach to economic analysis as tracking prices, wages and unemployment. In other words, in the spirit of Marshall McLuhan’s aphorism, the media is the market.