We are turning the world inside-out. Massive mining operations rip into rock, unearthing lithium, coltan and hundreds of other minerals to feed our gargantuan appetite for electronic stuff. Sand dredged from riverbeds and ocean floors becomes concrete; so far, there’s enough to cover the globe in a 2mm-thick shell. Oil sucked up from the seabed powers locomotion and manufacturing, and serves as the chemical base for our plasticised lives. We could easily wrap our concrete replica in plastic wrap.

Inverting the planet is messy. Retrieving all those minerals requires boring through tonnes of what the mining industry refers to as ‘sterile material’ – a revealing term for matter it perceives as purely obstructive, without use, infertile in every way. A typical 14 karat gold chain leaves one tonne of waste rock in South Africa. Obtaining the lithium that fuels cellphones and Teslas means drilling through fragile beds of salt, magnesium and potassium high in the Chilean Andes, producing piles and pools of discarded materials. More than 12,000 oil spills have defiled the Niger Delta. All this and more, so much more, from extraction alone.

Earth-systems scientists portray these processes with hockey-stick curves. Starting in the second half of the 20th century, their disturbing asymptotic graphs show a ‘great acceleration’ in the squandering of planetary materials. Some exponential increases can be measured directly, such as those for carbon dioxide or methane; others require extrapolation, like what’s left behind by dam building or motorised transport. Either way, the result is clear. Materials and molecules discarded in the course of planetary inversion do not disappear – instead, they move around, rising into the atmosphere, spreading out across once-fertile soils, seeping into waterways. We are worlding our waste.

Humans have always produced discards. But discards become waste only if they aren’t metabolised in a meaningful way. Consider the stuff emitted by our bodies on a more or less daily basis: pee and poop. Many societies have thrived by deploying, rather than discarding, human faeces. Pre-industrial Japan monetised excreta; as the historian Susan Hanley writes, in Osaka, ‘the rights to faecal matter … belonged to the owner of the building, whereas the urine belonged to the tenants’. For 4,000 years, China sustained an agricultural system using human stool as fertiliser. In the early 20th century, more than 180 million tonnes of human manure were collected annually in the Far East, according to estimates made in 1911 by the soil scientist F H King – amounting to 450 kilos per person per year, and enriching the soil with more than 1 million tonnes of nitrogen, 376,000 tonnes of potassium and 150,000 tonnes of phosphorus.

Admittedly, King might have overestimated: those figures equate to 1.2 kilos (2.6 pounds) of poop per person per day, which seems like a lot. Nevertheless, it’s hard to dismiss his subsequent comment:

Man [by which King meant white settler American men] is the most extravagant accelerator of waste the world has ever endured. His withering blight has fallen upon every living thing within his reach, himself not excepted; and his besom of destruction in the uncontrolled hands of a generation has swept into the sea soil fertility which only centuries of life could accumulate …

That was just over 100 years ago. Prophetic? Not really: King drew his conclusions from observations. Better to read this as yet another ‘Don’t say I didn’t warn you’ from a scientist.

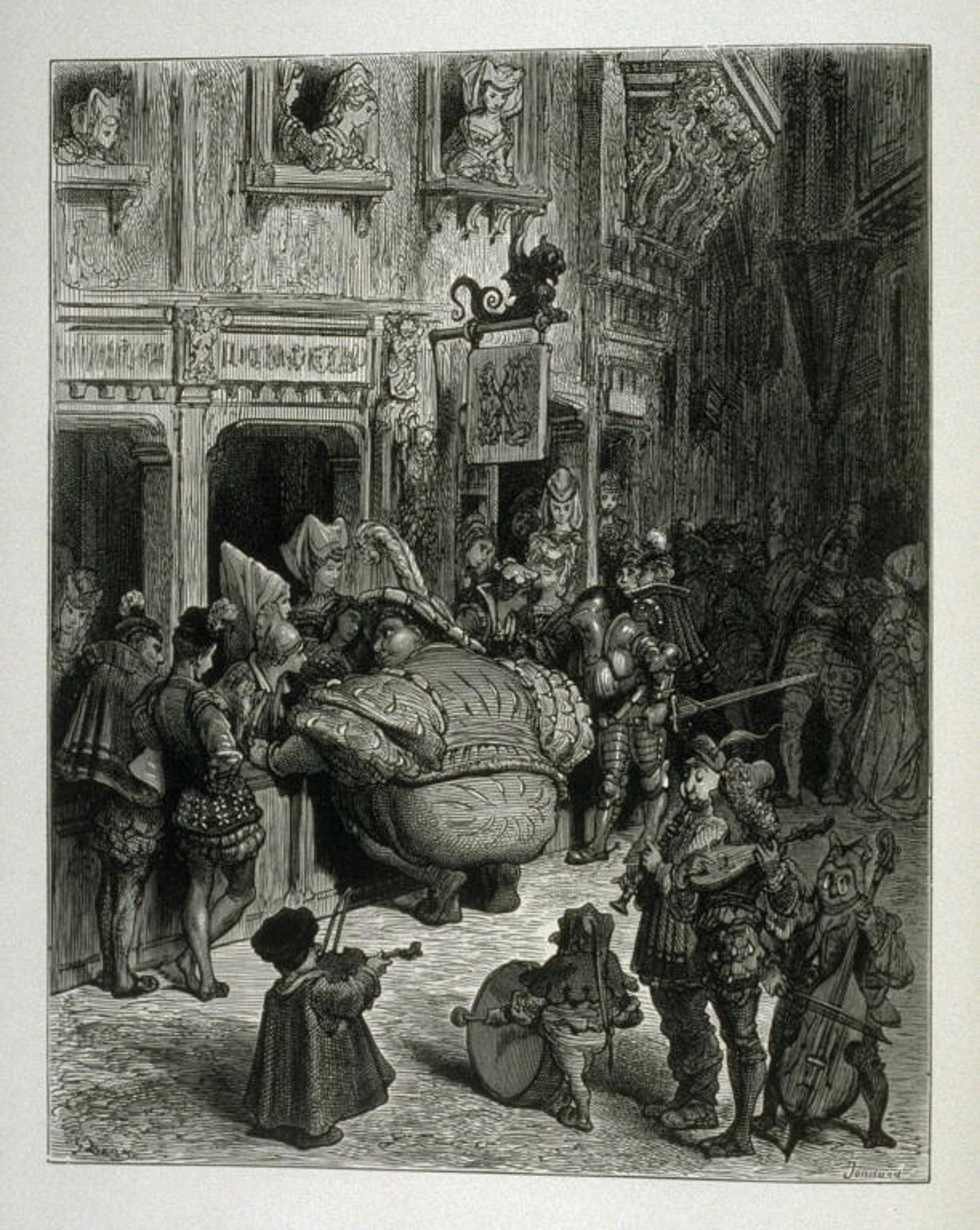

Gustave Doré’s illustration of Rabelais’ Gargantua. Courtesy Fine Art Museum of San Francisco.

Yet pooping can be pleasurable as well as practical. The 16th-century French author François Rabelais wrote not just about the gluttonous delights of food ingestion, but also of the ecstasy of its evacuation. Responding to his father’s question about how he stayed clean, the five-year old Gargantua of Rabelais’s fiction offered up a long list of options he’d tried, ranging from neckerchiefs to nettles. None could compare to his top choice, though:

I say and maintain that of all torcheculs, arsewisps, bumfodders, tail-napkins, bunghole cleansers and wipe-breeches, there is none in this world comparable to the neck of a goose, that is well downed, if you hold her head betwixt your legs … You will thereby feel in your nockhole a most wonderful pleasure, both in regard of the softness of the said down, and of the temperate heat of the goose, which is easily communicated to the bum-gut and the rest of the inwards … even to the regions of the heart and brains … The felicity of the heroes and demigods in the Elysian fields, consisteth [n]either in their Asphodel, Ambrosia, or Nectar, but in this: … that they wipe their tails with the necks of a goose.

A startling image, very much of its time. Today, we might take it as an allegory for the relentless pursuit of comfort and pleasure, weirdly resonant with the contemporary affordances of modern middle-class existence. Three-ply ultra-soft toilet paper offers a facsimile of this Rabelaisian downiness, while capitalist infrastructures enable poopers to treat all of it – faeces and wipes alike – as disposable. Just flush it all away. Don’t think about where it goes. No need to wash the goose.

Disposing of dung is historically and culturally contingent. For a time, Europeans used human excreta in tanning and saltpetre manufacture. When 19th-century travellers returned full of admiration for the large-scale use of human fertiliser in China and Japan, chemists approvingly explained that, when treated properly to remove harmful bacteria, poo returned nitrogen to the soil. The smell made human manure a hard sell, though. Lamenting the wasteful practices of capitalism, Karl Marx noted in Das Kapital (1867-83) that London found ‘no better use for the excretion of four and one-half million human beings than to contaminate the Thames with it at heavy expense’. Indeed, the English public health reformer Edwin Chadwick had better success persuading French officials, claiming to have convinced emperor Napoleon III of the virtues of sewage farming for cattle feed:

I prevailed upon the late Emperor to order some trial works to be made with sewage manure … A cow was selected, and sewaged and unsewaged grass was placed before it for its choice. It preferred the sewaged grass with avidity, and it yielded its final judgment in superior milk and butter of increased quantity.

In Paris Sewers and Sewermen (1991), the historian Donald Reid describes how Parisian municipal engineers scaled up the excremental experiments, filtering and treating human sewage in order to transform ‘formerly barren land’ into lush soil where vegetables grew ‘with an inexpressible vigour’. Sewage farming thrived in some Paris suburbs until after the Second World War, when a rise in land prices made it unprofitable. (Strike another notch in the ‘Marx was right’ column.)

For wives and daughters, finding the right time and place to relieve themselves poses more serious challenges

Sewage success notwithstanding, European reformers couldn’t match the scale, efficiency, and health standards of the practices in China or Japan. That didn’t stop Europeans convincing themselves of their sanitary superiority over their colonial subjects. In the early decades of the 20th century, colonial officials invoked public health (and the ‘civilising mission’) when redesigning cities in Morocco, Madagascar and elsewhere. Planners razed and rebuilt dwellings, seeking to shield European settlers from the excretions of their African neighbours. In the same period, American imperialists in the Philippines implemented a suite of faecal laws; the historian Warwick Anderson describes these as ‘excremental colonialism’. In apartheid South Africa, unequal access to infrastructure formed the foundation of racial hierarchy, to the point that domestic servants were prohibited from using the very toilets they scrubbed for their employers. Segregation in the name of sanitation became a tool of colonial rule.

Defecation can be dangerous, even deadly. The United Nations estimates that some 673 million people have no choice but to evacuate their bowels out in the open. Not everyone views this as a problem, mind you. Many male farmers in India, for example, poo quite peacefully on their plots first thing in the morning. For their wives and daughters, however, finding the right time and place to relieve themselves poses more serious challenges. Doing it in daylight leaves them vulnerable to harassment and shaming. Doing it under cover of darkness can invite interruption from wild animals – or rapists. Avoiding such dangers requires maintaining bowel control at an early age. One mother in Rajasthan explains: ‘I make my children sit on the wooden legs of the cot if they get nature’s call at night so that the pressure can go, because I cannot take my young kids for defecating alone at night.’ Beyond discomfort, pooing in the open poses health hazards. The absence of water to wash up, flies’ fondness for faeces, and a variety of other vectors create multiple pathways for food contamination. The World Health Organization estimates some 800,000 deaths a year from the resulting diarrhoea. When cholera strikes, all bets are off.

Defecating with dignity poses even greater difficulty for the urban poor. Rising urban density both obliterates privacy and massively increases the scale of the problem. Cities challenged to provide running water don’t have the infrastructure for flush toilets. Under the best of circumstances, well-maintained latrines can provide safe spaces for attending to sanitary needs. Some municipalities endeavour to provide basic facilities for their neediest denizens. Others leave people to fend for themselves. To the delight of neoliberal policy wonks, some of these independent endeavours can be quite successful. In the city of Tema on the coast of Ghana, communal toileting facilities have become lucrative private enterprises. In Kampala, the capital of Uganda, creative entrepreneurs convert waste into energy, manufacturing fuel bundles such as ‘My Kook’ energy briquettes (their slogan: ‘glow to replenish nature’). Still, shit must be shovelled to become a resource; latrines must be emptied to be effective. And this is dirty, low-status work the world over. Crap has a way of clarifying – and escalating – social divisions.

Size matters. In the early flush of enthusiasm for toilet hookups, who could have foreseen the consequences of using drains for all manner of waste? Or imagined the advent of disposable diapers, for that matter. By the early 21st century, London’s 19th-century sewage system was regularly experiencing severe blockages, which officials gleefully dubbed ‘fatbergs’. Thames Water recently described one of the largest ever found:

the extreme rock-solid mass of wet wipes, nappies, fat and oil weigh[s] the same as 11 double-decker buses. It is blocking a stretch of Victorian sewer more than twice the length of two Wembley football pitches, and weighs in at a staggering 130 tonnes.

Only truly colossal fatbergs make the news these days. But smaller blockages still abound, jamming the pipes at an average rate of 4.8 times an hour. Clearing them costs Thames Water around £1 million a month.

The problem isn’t that the Victorians designed bad sewers. Instead, it’s the seduction of disposability, as well as the ad campaigns and corporate incentives that have cultivated and sustained its allure since the early 20th century. None of this was inevitable. At the dawn of disposability, many found the practice distasteful. The two world wars slowed the march of throwaway culture too, since wartime requires careful stewardship of materials. Mind you, recycling isn’t inherently righteous: the historian Anne Berg has shown, in dreadful detail, how the Nazis excelled at re-use, making a virtue of collecting not only inert materials but also human remains. Rationing continued throughout western Europe (and across the Iron Curtain) well into the 1950s, as societies struggled to rebuild amid chronic shortages. In the early 1970s, environmentalists advocated for continued frugality, recasting the moral frame of recycling in planetary terms.

Nevertheless, disposability carried the day. The geographer Max Liboiron argues that American industry – deliberately, and with great dedication – promoted disposability through a variety of manufacturing, packaging and distribution strategies, ranging from planned obsolescence to fast fashion. Contrary to popular discourse, humans are not inherently wasteful; rather, Liboiron notes, that claim ‘came into being at a particular time and place, by design’. By 1963, a packaging industry executive could triumphantly praise his colleagues in plastics:

You are filling the trash cans, the rubbish dumps and the incinerators with literally billions of plastics bottles, plastics jugs, plastics tubes, blisters and skin packs, plastics bags and films and sheet packages – and now, even plastics cans. The happy day has arrived when nobody any longer considers the plastics package too good to throw away.

The film The Graduate (1967) immortalised the triumph of polymers for a popular audience. In the movie’s best-known sequence, a middle-aged Mr McGuire pulls the young college graduate Ben aside at a cocktail party to offer some career advice:

McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Ben: Yes, sir.

McGuire: Are you listening?

Ben: Yes, I am.

McGuire: [Dramatically.] Plastics!

Ben: [Pauses.] Exactly how do you mean?

McGuire: There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?

Ben: Yes I will.

McGuire: Shh, enough said. That’s a deal.

The exchange became a generational trope, with ‘plastics’ cast as a symbol of the consumerism that the hippies yearned to flee. But escape proved impossible. By the late-1980s, even dissent had become commodified; just consider the proliferation of Che Guevara paraphernalia in shops peddling ‘counterculture’ curios.

When you get to the bottom of it, much of what’s marked as municipal solid waste would be better off as industrial waste. The category matters, because most consumers don’t have the luxury of avoiding single-use plastics. We’re trapped. As individuals, we can dutifully sort discards, compost food waste, and reuse to the max – and still not make a dent in the exponential expansion of (often toxic) waste. Does this mean we shouldn’t bother? Absolutely not: among other things, such habits can raise awareness, strengthen citizens’ commitment to a just planetary future, and build support for stronger, more systemic reforms. Maybe, just maybe, they encourage some people to consume less. But they’re not a fix. In her book Recycling Reconsidered (2013), the waste policy expert Samantha MacBride lambasts what she calls ‘pure every-little-bit-helps-ism’. The recycling movement, however well-intentioned, has put the spotlight too squarely on the individual consumer. That’s made it easier for recycling to be co-opted by manufacturing companies, eager to maintain the status quo of selling new products ad infinitum.

Too much attention on individuals also distracts from what to do about industrial waste – much of it enduringly toxic, and all produced at a far larger scale than municipal trash. Right-wing libertarians rely on this fact to argue that waste collection must be fully privatised, and/or that recycling is pointless. Instead, MacBride insists, the data demonstrate that solid-waste management – in all its forms, from all sources – must be handled by public, well-regulated institutions. In her study of communist Hungary, the sociologist Zsuzsa Gille offers a salutary example. In the postwar period, the country tried to use industrial waste as a resource. This goal acquired particular virtue in the context of Cold War ideological competition, because – tellingly – it contrasted so starkly with capitalist practices. In later decades, however, Hungarian waste management was privatised. It devolved to a ‘chemical waste model, in which waste was primarily seen as a useless and even harmful material’. This approach focused on technologies at the end of the pipe: waste management instead of waste prevention. Today, chemical residue regimes are dominant the world over.

We now face a plastic tide – soon, a tsunami. Oceanic garbage ‘patches’ form soupy masses of microplastics. Albatross and whales wash ashore, their stomachs stuffed with human trash. For years, the US exported its ‘recyclables’ to China – until the Chinese government set a standard of plastic purity so high that US trash couldn’t make the grade. The US recycling industry rapidly pivoted to other Asian nations. As MacBride has argued, this sideways step shows how the recycling industry does next to nothing for resource conservation and offers weak outcomes in terms of energy or pollution reduction.

It’s now so obvious that recycling exports are engines of inequality, even a child can see it. Literally. Here’s a passage from a letter handwritten by 12-year-old Aeshnina Azzahra of Indonesia, addressed to the US president in July 2019:

My country is the second largest contributor to waste in the world. And some of that waste is your waste.

Why do you always export your waste to my country? Why don’t you take care of your own waste? Why do we have to feel the impact of your waste? In Indonesia right now the river is very dirty and smelly. We cannot [go] swimming, fishing, and have fun in the river … Many factories dispose of their waste carelessly, into the river, to the fields, and … under the houses of villagers. Mostly the factories recycle your waste …

#TAKE BACK YOUR TRASH FROM INDONESIA

Please answer my letter.

With respect,

Aeshnina Azzahra

The only naive note in this letter is the request for a reply from her nearly illiterate addressee. Otherwise, as the Indian writer Vijay Prasad notes, the adolescent Azzahra has a pretty good grasp of the geographies of imperialism. And she knows, first-hand, something that most Americans don’t think about: recycling can be a dirty, profit-oriented business.

The more we make, the more we waste. But this ‘we’ isn’t universal. It relies on exclusion and exploitation – dynamics glossed as ‘externalities’ by the institutions of predatory capitalism and the economists who legitimise their actions. Since 1950, industry has produced more than 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic. Of this, 6.4 billion tonnes have ended up as waste, the vast majority originating in rich countries. Only 9 per cent of this total has been ‘recycled’; another 12 per cent has been incinerated. The rest has gone to landfills, or been left to its own devices. The cheapest of these plastics cannot be recycled at all; abandoned, the materials break down into microplastics, leaching persistent organic pollutants along the way. The ethos of endless growth is nurtured daily by the idea of disposability, and by media reports of expanding economies (good) or stagnating ones (bad). It’s a fantasy that feeds on twin figments: the planet is infinite, and discards disappear. Wastepickers in Cairo, Delhi, Durban, Rio and beyond know better. Their livelihoods depend on discards. It’s easy to dismiss the poorest of the poor as living in the past. It’s harder to acknowledge that, actually, they might be living in the future.

Those who call out the absurdity of growth have been mocked for years. Look at the reactions to The Limits to Growth (1972), the prominent report that used computer simulations to show how unchecked accumulation would produce planetary collapse. Take-downs quickly followed, as eminent economists scoffed at such crude and implausible scenarios. Critics insisted that technological progress would overcome pollution and resource depletion. As if technologies could be made from nothing. As if toxic waste could disappear into thin air. As if air itself weren’t becoming thicker with particulates by the day.

Those who insist that the only path to planetary stability is via degrowth face derision

It’s true that The Limits to Growth relied on simplified simulations, but its central tenets remain unassailable: the planet is not infinite, and you can’t make something from nothing. Recent, more robust research has vindicated many of the first report’s findings. Which throws a major kink into another seductive fantasy that animates public debates about humanity’s future: sustainable development.

The romance of sustainability calls for sacrifice and ingenuity, as do all popular romances. The rich must forgo disposability and commit to reuse with the help of ‘smart’ systems. The Sun and the wind will provide a boundless fount of energy, powering the ‘internet of things’ (and screens). New technologies will alleviate poverty by enabling women to cook without burning wood and children to do their homework after dark. Done right, the tale goes, such measures can generate a ‘good Anthropocene’, in which growth continues and everyone thrives. Those who object – who insist that the only path to planetary stability is via degrowth – face the same derision hurled at their predecessors behind The Limits to Growth.

Yet the technologies trumpeted by so-called ecomodernists dump discards at every step – from manufacturing to distribution and use. So you mustn’t limit your gaze to rooftop solar panels in Arizona: notice, too, the dead fish in China’s Mujiaqiao River, where one of the world’s largest photovoltaic manufacturers is known to have spilled hydrofluoric acid. Don’t cry victory over improved emission standards in Europe without acknowledging that cars that don’t make the cut are exported to Africa, where they get a second shot at ruining people’s lungs. Don’t reduce the criteria for technology assessments to carbon emissions, when not a single community in Japan has agreed to host the millions of cubic metres of radioactive topsoil removed from Fukushima prefecture after three (low-carbon) nuclear reactors exploded there.

‘Sustainable development’ is an oxymoron. Its promises of plenty lull consumers in rich countries into imagining goods without waste – a world metabolism operating at peak efficiency. It’s a sweet dream. Comforting. And deeply alluring: city officials in San Francisco, where I live, appear to truly believe that they can formulate policies to attain ‘zero waste’. As a global hub of innovation, the city seems well-poised to implement the dream of a truly circular economy. Yet in its current form, the dream can flourish only because the reality remains invisible to the majority of city residents. In real life, most of San Francisco’s waste – whether sewage or recycling, whether from construction, diesel emissions or the toxic and radioactive legacy of our decades as a naval hub for Pacific nuclear testing – ends up in Bayview-Hunters Point, a neighbourhood ignored by the city’s elite, whose prosperity depends on treating the community as a dumping ground.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s worth articulating ambitions for a circular economy. We in the wealthy world must strive to produce less waste, to find ways of fixing things, to repurpose materials that we used to discard. But don’t delude yourself, either. Any form of sustainable future (forget anything so grand as ‘development’) requires less for the prosperous among us, not more. Less stuff, less desire, less comfort, less convenience. Less of everything, really.

This essay will also be published by Stanford University Press in the forthcoming digital project ‘Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene’ edited by Anna Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena, and Feifei Zhou. Please visit sup.org/digital for more information.