Listen to this essay

25 minute listen

Watsuji Tetsurō (1889-1960) is best known today for his comprehensive analysis of intellectual history and ethical thought. In Japanese intellectual history, he is regarded as a pioneer in existentialism studies, publishing an early secondary resource on Friedrich Nietzsche and the first book on Søren Kierkegaard in Japanese in the 1910s. His investigation into Japanese ethics is also known for its critical engagement with Western philosophers and thought, including G W F Hegel’s dialectic and Martin Heidegger’s phenomenology and hermeneutics.

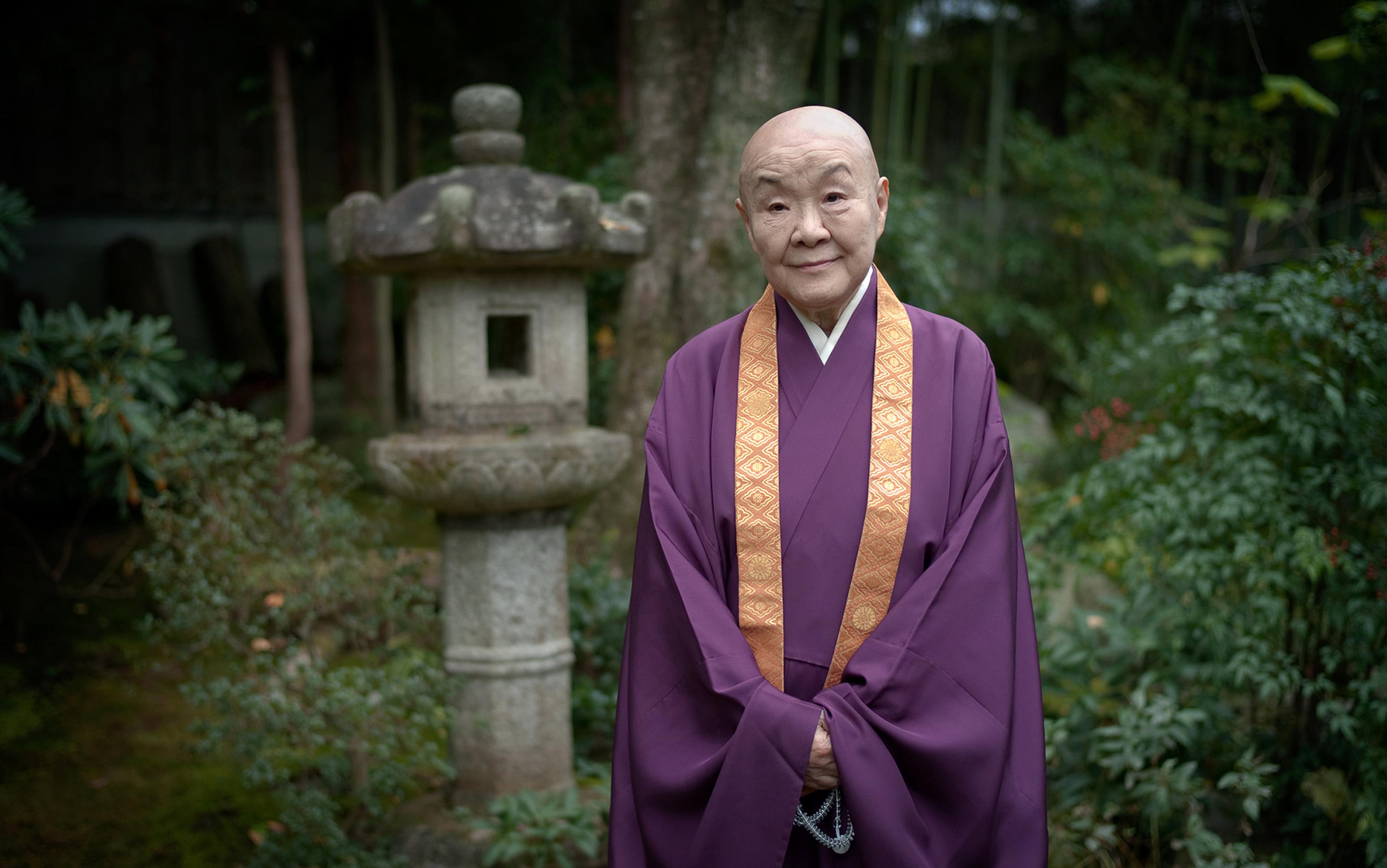

An undated portrait of Watsuji Tetsurō. Courtesy of the National Diet Library, Japan

In 1934, Watsuji laid out the methodological foundation of Japanese ethics with his Ethics as the Study of the Human [ningen], and gave the earliest formulation of Japanese environmental ethics in Fūdo (1935) – translated as Climate and Culture: A Philosophical Study. He then published his magnum opus, Rinrigaku – translated as Watsuji Tetsurō’s Rinrigaku: Ethics in Japan – which was originally a series of essays written between 1937 and 1949, during one of the most tumultuous periods for modern Japan (and, indeed, the world).

In Rinrigaku, Watsuji argues that ethics is the study of what it means for us to be human. How we think about the nature of human existence, he says, dictates the ways in which we understand our ethical values. Hence, he criticises Western philosophical conceptions of the modern subject, arguing that the Western rendering of subjectivity is both problematic and foreign to the ways in which what it means to be human (ningen, 人間) has been thought about for millennia in East Asian and Japanese philosophy.

First, Watsuji shows that the conception of the Western subject is both individualistic and self-referential, although most ethical systems have tried to paint it as being universal. Take the example of the Cartesian ego, derived from his cogito argument. René Descartes locked himself in a room, then decided to doubt his perception, among other things, concluding that, even when he doubted everything, he could not doubt his activity of thinking as the foundation of his subjectivity. To a Japanese reader, this is a story about a Frenchman who could afford the time to meditate on how his mind works, thereby laying out a reflection on his consciousness in his solitude. But then this Western philosophical model of thinking, which a solitary Frenchman set forth, somehow became the prescriptive model to describe the structure of the mind for all human beings.

Aside from appealing to the conception of divine transcendence that created the universe, nothing in this ego-cogito framework of epistemology suggests that we should think of our minds as working in exactly the same way as Descartes thought about his own mind in the 17th century. The same goes for Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative or Hegel’s dialectic of self-determining reason. The basic methodology of modern, Western philosophy is the same, according to Watsuji: a philosopher from a specific cultural and historical background reflects upon how they conceive of the structure of their mind, and declares that what we might call their ‘self-referential abstraction’ is the universal model that theoretically applies to every sentient being across all space and time. (We should also not forget that, in practice, many of these models denied certain demographics access to the universality of reason.) For Watsuji, this is deeply problematic as a foundation for a system of ethical thinking.

What Western philosophy describes as an intelligent modern subject looks more like an unreasonable despot

What makes the modern conception of the subject that commits this ‘self-referential abstraction’ so problematic, according Watsuji, is that it had to come up with a supra-individual self that aims at the happiness of society or the welfare of mankind, in order to cloak the foundational problem of individualistic self-centredness. What is worse, Watsuji argues, is that, despite this move towards intersubjective consciousness, the conception of the modern subject creates conflict between human subject as the source of ethical values, and the objective world or nature as meaningless ‘thereness’. Nature, in this case, is conceived of as a heteronomous other – a threat to human autonomy, an irrational outside entity that needs to be conquered through the self-determining intelligibility of ‘I think.’

At this point, what Western philosophy describes as an intelligent modern subject looks more like an unreasonable despot who believes themselves to be the highest form of conscious existence, or even a delinquent child who claims to be the sole determiner of world intelligibility, yet in truth is just severed from its mother, Nature. This, incidentally, is how Western subjectivity appears to most thinkers from a non-Western philosophical background. Watsuji is just one of many who, out of the same concern, proposed an alternative way of thinking about human existence through the system of ethics particular to his own cultural and intellectual milieu.

The Japanese conception of human being (ningen sonzai, 人間存在) in the larger context of East Asian philosophies is radically different from the Western conception of humanity. What makes us human (ningen) is not the ontological structure made by the first principle or divine transcendence. Nor is it reason, spirit, nor even the metaethical structure of meaning that provides a theoretical ground for our ethical values, but rather the ‘concrete practice of betweenness’ or ‘in-betweenness of act connections’ that constitute our humanity (ningen-sei, 人間性). And this practice of betweenness always already comes with the practical self-awareness of emptiness. How could we possibly be a human or an ethical being without God, or reason, or the universal ground of modern subjectivity or of meta-ethics?

To conceive of the nature of human existence in Japanese philosophy, Watsuji argues that we must make a double de-/re-constructive movement away from the European conception of humanity as the modern subject. First, we must deconstruct the fixed notion of the self that we inherited from the history of European philosophy – Alexander Douglas made a similar point with regard to an argument with Zhuangzi on the non-substantial nature of the self (or ‘non-self’) in his Aeon essay ‘Essence Is Fluttering’ (2025). Second, we must then triangulate the proper understanding of human existence as a dynamic life in the midst of the world. This is to reconstruct our sense of who we are in our active engagement with each other in our inseparable relation to history, society, culture and climate (including all sentient beings and natural environments therein).

Imposing a fixed conception of the human subject as something irreducible to its objective environment is very foreign to most Asian and Buddhist thinkers, whether it is conceived as the soul or integrity of human existence as created in the image of the divine in the Judeo-Christian tradition, or as the possessor of reason or spirit, in line with a secular understanding of the human subject. As Douglas’s Daoist essay shows, some Asian thinkers (including Watsuji) even go so far as to say that this fixed, essential conception of subjectivity is delusional because it suffers from a propensity to view each human as a ‘self-sustaining being’, abstracted or removed from their social, historical and climatic/natural groups.

In Buddhist philosophy, this logic of emptiness also requires an act of self-negation and compassion

The world is always in flux and uncompromisingly dynamic. If we have a chance to travel to different continents and to different parts of large nations, we quickly learn how vastly different our ways of living, modes of communication, art media, senses of histories and so on can really be. But Western philosophers succumb to the temptation to hold on to a fixed notion of the self that exists independently of that uncompromisingly polyphonic world, so that we can somehow construct a universal theory of ethics through the self-referential universalisation of individual consciousness. And because Western philosophers and those in their thrall prioritise one model that drives towards universal ethics through its self-centred modelling, we endure the problem of colonial thinking that privileges the European way of thinking about what it is to be human above all other alternative conceptions.

Instead, Watsuji’s understanding of the existence of ningen adopts the dialectical structure of dynamic individuality and polyphonic open totality derived from the Mahayana Buddhist notion of emptiness. This concept (which also has a Daoist influence) is meant to break down a fixed conceptualisation of what humans, or anything else, should be across infinite space and time. It means that we cannot ultimately fix any definition of anything because nothing remains what it is forever: every thing is in flux, and nothing is fixed. Everything must ultimately turn to nothing and, thanks to this ‘turning into nothing’, everything has a space to be what it is. The world is made of this endless cycle of what the Heart Sutra calls ‘form and emptiness’, and in Buddhist philosophy, this logic of emptiness also requires an act of detachment, self-negation and compassion (that is, for a self to give room for others to be what they are, or are becoming, as others do the same for the self). Watsuji uses this concept of self as emptiness, or what Buddhists call ‘interdependence’, to ground Japanese ethics as the study of the human, a culturally specific grasp of human existence as ningen.

A Buddhist defence of the concept of emptiness (pace Daoism) goes something like this: because there is no fixed essence to human existence (the doctrine of ‘no-self’), each group of individuals in a specific historical, cultural and natural milieu can constitute their sense of humanity with their self-awareness that this place-specific conception of their inter-relational humanity is both transient and finite. But because they practise self-negation – a detachment from the temptation to essentialise their self-conceived notion of themselves beyond their transient existence – they can be truly aware of themselves. This is often expressed in Buddhist language as enlightenment or no-self, as a manifestation of existential totality (of the ways the world and the self are) as emptiness.

Unlike the Western ethics that strives for the perennial conception of self as a being with a fixed, unchanging, discoverable essence, Japanese ethics strives to become aware of the self as a temporary and finite expression of what it means for it to be a self-emptying human. Watsuji, then, argues that each language necessarily contains this dialectical structure of the interplay between being and emptiness, and that the Japanese language (rooted in classical Chinese and other Asian intellectual traditions) has a peculiar way of preserving the speaker’s awareness of this dialectical thinking.

You must empty your cultural and personal assumptions when allowing me to speak about my culture and myself

Regarding languages, Watsuji argues that:

No one person has the privilege of declaring that she alone has created [words]. In spite of this, for everyone, words are one’s own. Words are the furnace by means of which merely subjective connections made by individual human beings are converted into noematic meanings. In other words, words are concerned with the activity whereby preconscious being is turned into consciousness.

‘Noematic meanings’ are ideas, perceptions and thought contents that we recognise as being a part of our subjective consciousness, apart from the objective world. Watsuji is saying that the world is a cluster of practical act-connections and, in order for me to express my thought or feeling therein, then, we (including you and I) must engage in the dialectical interrelation of parts and the whole through the praxis of emptiness prior to the rise of noematic meanings.

It should be easy for us to understand this self-negating dialectic of emptiness if we compare the relation of self and language with that of author and reader in reading the words of this essay now. In order for me to express myself in this article, every reader (you) would have to give me a space to do that in my own terms. There is a sense of self-negation needed from your side as the audience if you are not to impose your understanding of the world or yourself on my explanations of the Japanese worldview. You must empty your cultural and personal assumptions as much as you can when allowing me to speak about my culture and myself for a few pages. But, at the same time, I must know how you, as the readers, speak this language so that I can anticipate misunderstanding.

In addition to knowing how the English language functions, with its peculiar grammatical rules and unique punctuations, I have to think with the editors about how we can best connect the idea with the target readership, many of whom will come with a very different set of cultural norms and knowledge from my own. There is a sense of self-negation on our side as writers, in that we do not entirely impose our scholarly understanding of Japanese philosophy in its original form, a form that would make sense only to specialists familiar with Japanese history, philosophy and language. A good article usually consists of the balance between these two sides of self-emptiness.

When the author fails to achieve such a balance, the result is often a highly abstract article that few can understand, or else one that allows readers to project their opinions and pre-existing prejudices on the article with the result that the authorial intent escapes, and they interpret the article in an entirely subjective way. Watsuji argues that the same dialectical relation of mutual self-negation as a basis of human communication takes place in the balance between individual speech acts and language. Because of that, if we look at how a language functions in relation to its speakers, and vice versa, through this model of dialectical emptiness, Watsuji thinks we will better understand how ethics is both practised and theorised in each domain of world philosophies in general and in Japanese philosophy in particular.

If language is a constitutive depository of our experience, as Watsuji argues, paying attention to how a set of philosophical terms in a particular language functions with its symbols and rules can help us understand how we articulate the sense of what it means to be human, and to be ethical, in that culturally specific framework of thinking. In this sense, Watsuji invites us to explore the function of Japanese words as rinri (ethics) and ningen sonzai (human being) and to capture distinct ethical concepts in the Japanese intellectual tradition.

In Japanese ethics, both the conception of ethics as rinri and of human existence as ningen sonzai retain the strong mutual implication of such opposing terms as individuality and totality, singularity and plurality, and self and other. The term rinri, meaning ‘ethics’, consists of two characters: rin (倫) and ri (理). Rin refers to fellows or nakama, a group of sentient beings that follow a certain set of relational rules, or what Confucianism calls ‘constancies’. This includes the ways in which we relate to each other as parent and child, brother and sister, husband and wife, minister and subject, and so on. Once again, these relational roles are not fixed: the ways in which partners relate to each other do not have to follow one model. But they are determinable expressions of human relations that retain some communicable patterns, which are always subject to change. Additionally, the Japanese term nakama, or fellows, signifies both singularity and plurality. We can point to a person to say that he is our nakama (an ally) or describe ourselves as nakama (friends). It retains both meanings of singularity and plurality.

Ri (理) is often translated as principle(s) or reason in the context of philosophy but it also refers to a kind of sensible pattern (kata) or conventional agreement through which we constitute our relations. There are certain expectations or constancies in the ways that we write our essays or relate to each other as friends or families. Once again, these are not fixed rules that have to be permanently observed in the same way but are a relatively stable aggregate of social, cultural and climatic behaviours through which we constitute our sense of belonging and mutual understanding. Thus, ri refers to the patterns of interactions that constitute the sense of what it means for us to be human (ningen).

The character 門 symbolises a Buddhist temple gate, which is usually open

The term ningen consists of two characters, nin or hito (人) and gen or aida (間). A combination of these characters is also dialectical, through and through. The term nin or hito usually means a person or a human but also retains some sense of plurality as ‘humanity’ or ‘mankind’. As we can imagine from the shape of the Chinese character, 人 indicates two persons supporting each other to constitute a sense of a person or personhood. In other words, in Japanese ethics hito or person is both singular and plural. If we lose the balance between the two, we lose the sense of what it means to be hito or person.

The second character, aida (間), consists of two parts, 門 and 日. The first character looks like the entrance to a saloon bar in a western movie. When the protagonist pushes through the swing door, the piano stops and everyone looks at him in silence. I think this is a good method of ‘remembering the kanji’, as the philosopher James Heisig put it. Indeed, the character symbolises a Buddhist temple gate, which is usually open, and we should be able to feel the hollow expanse behind it. The second character, 日, symbolises the sun: so, the sense of space is dictated by the temporal movement through the gate of the star (and also, probably, by the shadows it casts).

Watsuji shows that adding this character symbolising the spatial concept of betweenness (with some implication of temporal space) to the character of person or hito was not accidental. Rather, it indicates the historical fact that ancient Chinese thinkers, and Japanese thinkers as their critical followers, adopted the insight that human individuals cannot exist apart from the social-natural whole of their being in the world. Hence, for them, as much as for contemporary Japanese ethical theorists, what makes human existence is the ‘dialectical unity of those double characteristics that are inherent in a human being’. This ‘unity of contradiction’, Watsuji argues, does not remain within the bounds of what we call ‘humanity’ in Western languages, but the ‘concept of [betweenness, or the open totality] already involves the historical, climatic, and social structure of human existence’. He continues:

To see ningen only in the form of hito [ie, an individual human being] is to see a human being merely from the perspective of his individual nature. This view, if it be held alone, and even if it is allowed as a methodological abstraction, cannot come to grips with ningen concretely. We must grasp [the Chinese-Japanese sense of the human] ningen through and through as the unity of the … contradictory characteristics.

This dual structure means that, in order for an individual self to act, it always acts in relation to its betweenness, or the form of engagement that covers not only intersubjective relations but also the ways in which human beings interact with each other through their engagement with shared social, cultural, linguistic and natural environments.

The concept of betweenness that characterises the nature of human existence in Japanese ethics does not designate the sense of the world as a fixed place where we can find the sum total of natural objects. Since it is not a fixed place, we cannot give a determinate identity or framework that escapes radical change. We must instead imagine it as the hollow expanse behind the gate of the Buddhist temple, or as the clearing behind the shadowy protagonist in a western film. It implies an infinite possibility of interrelations that ground individuals, which allow them to express these interrelations as their social, cultural and natural belongings. It is the self-emptying dunamis (ancient Greek for ‘potentiality’ or ‘potency’) of what makes you and me, as the reader and the writer of this article, as much as it is the unfixed foundation sustaining our communication as the shared practice of mutual self-negation. The world consists of this pre-ontological space where we interact with each other to constitute our sense of polyphonic belongings.

Ancient Chinese and Japanese thinkers, who emphasise the dynamic interrelation between a single human being and the open totality of such individuals as they live and die in the midst of one another and nature, refer to the dynamic space of social-natural community, where both the world and the individual exist in their contradictory and mutually implicated relation. The betweenness of ningen is pure transformation, that is to say, it is, as a concept, empty in and of itself, but it calls for the practical negation of each person’s self-centredness for the realisation of the other and vice versa. Like the Buddhist notion of codependent origination or emptiness, the principle of self-negation is the movement between the zone of being and of non-being, not as a victim of self-determining reason, but as an open community of compassionate beings who allow each other to express themselves in their own terms. It allows them to be understood fully in relation to each other.

There are many interesting implications from this Watsujian conception of Japanese ethics as rinrigaku. One of the more remarkable implications is that, as early as the 1930s, Watsuji was laying the foundation for decolonial ethics by practising the intellectual genealogy of ethics as the study of human existence in relation to each subfield of world philosophies, rather than taking the more usual Western route of seeking a universal ethic. This is to say that every philosophy programme that specialises in ethics – ranging from the traditional theoretical exposition to applied fields, such as medical and environmental ethics – should encourage its researchers to gain fluency in different languages and to investigate various historical ways in which ethics has been both conceptualised and lived in different spheres of world philosophies.

If we care to move beyond the colonial, self-referential abstraction of Western universal ethics, Watsuji argues, we should practise ethics based on different cultures and languages, beyond the confines of Anglo-European philosophy. Unlike the Western anthropocentric formulation of ethics that sets forth a self-subsisting subject apart from nature, Japanese ethics starts with an assumption that each individual, and each group of such individuals, constitutes their sense of what it means for them to be human always already in their interrelation with their social, historical and natural surroundings. Japanese ethics, in this sense, does not add one subfield to the discipline of ethics but opens up its border to a plethora of world philosophical formulations of ethical thought.