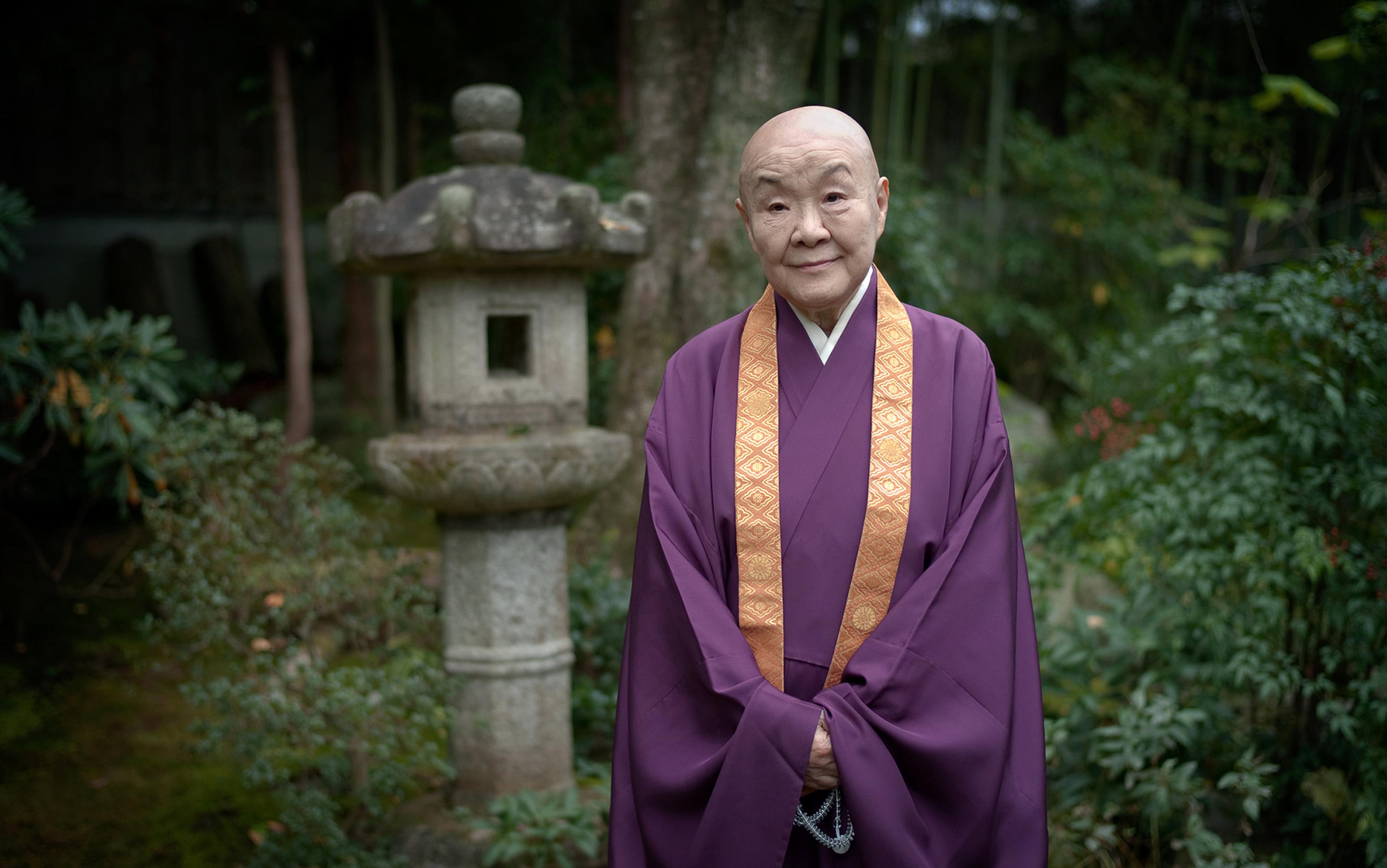

Jakucho Setouchi’s eyebrows work themselves into an intimidating ‘v’ as she lays into the ‘vulgarity’ of Japan’s political class, and she describes one up-and-coming politician as ‘a little Hitler’. The 90-year-old woman sitting opposite me, bald and black-robed, brims with a mixture of gentleness, raucous laughter, and unexpected steel. A little leaf-wrapped delicacy sits untouched in front of me, as I try to get used to the idea of hearing a nun’s confession.

I’ve come to the green outskirts of Kyoto, to the home of possibly the most famous woman in Japan outside the royal family. Setouchi might be said to be royalty of a sort herself: the nation’s teacher, its conscience, one of its harshest critics. She first found notoriety in the 1950s when she left her family for a romance with one of her husband’s students and began her controversial career as a novelist. She’s lived several lives since then; perhaps the greatest transition came in 1973 when she took Buddhist vows and received the name ‘Jakucho’, which means ‘silent, lonely listening’.

Today she is known for her vigorous opposition to the death penalty, for journeying to Iraq after the first Gulf War to distribute medicine, and for purchasing newspaper space to condemn its disastrous sequel. In May this year her distraught assistants watched her stage an outdoor hunger strike in the blazing summer sun. She was starving herself in protest at the reopening of Japan’s nuclear facilities following the Fukushima crisis, which she likened to the atom bomb attacks during the Second World War.

Meeting Setouchi, one gets a sense of raw power: of a person who can speak without the self-preserving self-censorship that’s routine to most of us. This applies equally to talk of her past, and to a brief, little-known encounter with mental illness in the mid-1960s that helped her on the road to her present life. This is the confession that I’ve come to hear.

‘I didn’t notice at the time,’ Setouchi tells me, ‘but I was starting to drop things, starting to become a bit strange.’

She was talking obsessively at her friends — non-stop and, on one occasion, right through the night. The tangled relationships with men that she’d turned into her first major literary success in 1963 — Natsu no Owari (The End of Summer; scheduled for release as a film next year) — had finally overtaken her. At 40, she was proud of having survived on her own wits and talent since her divorce. She had weathered allegations of pornography against her early work and could count luminaries such as Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima among her friends. Yet there she was, suffering what she would later call the total loss of her power of judgment.

After she narrowly avoided injury trying to walk up the down escalator of a Tokyo department store, her friend Haruko Shibaoka launched the 1960s equivalent of an intervention. Setouchi, who seems to have disliked doctors back then as much as she says she does now, reluctantly agreed to seek help.

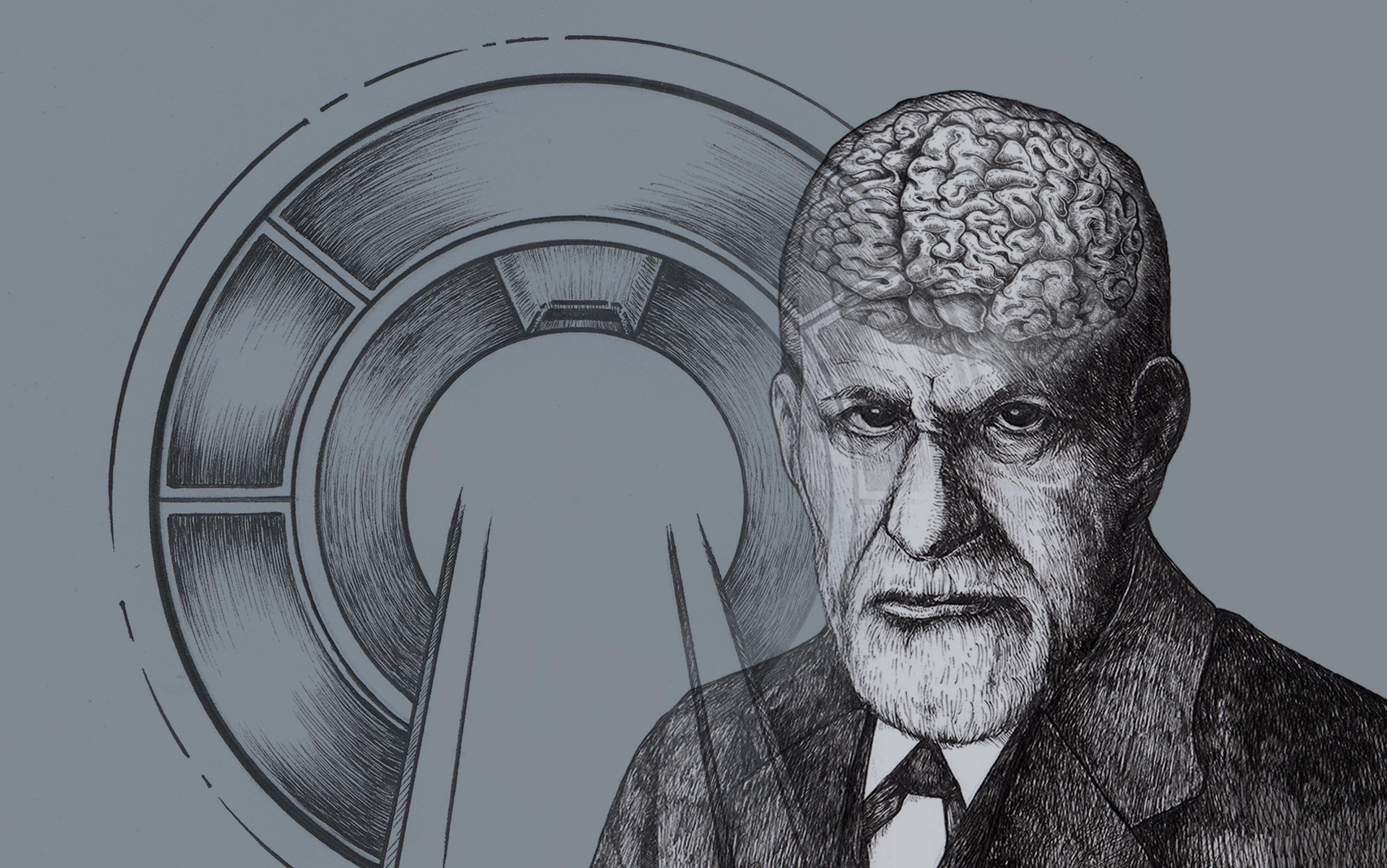

There was a doctor living in the fashionable Den-en-chofu area of Tokyo. He had studied with Sigmund Freud and his circle in Vienna in the early 1930s. Now he was retired and his health was failing. Nevertheless, Shibaoka was a long-standing client and friend, and she was confident that he would agree to see Setouchi. They went to his house, and knocked on his door. And so the novelist became the last ever client of Japan’s first ever psychoanalyst, Heisaku Kosawa.

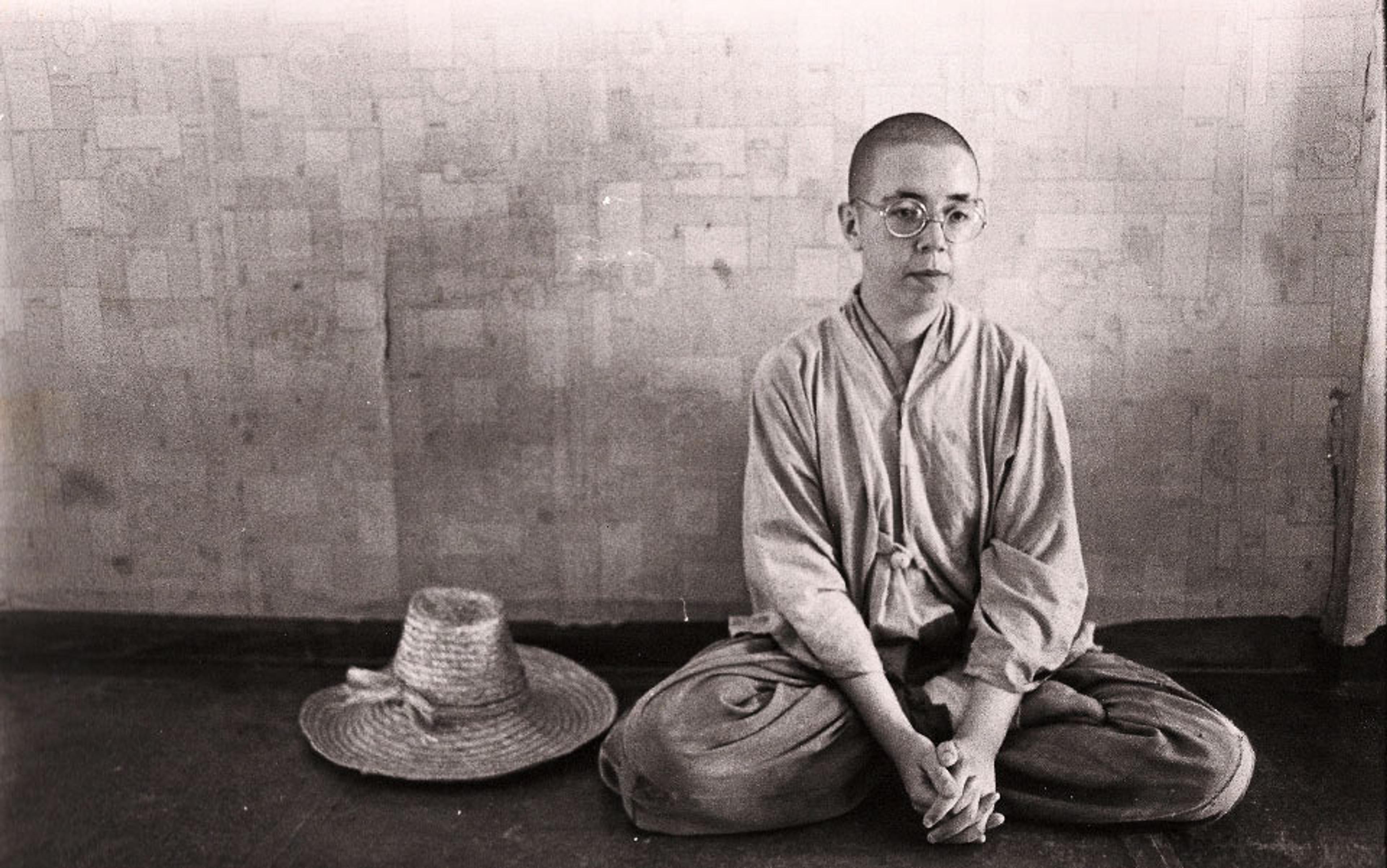

In his youth, Kosawa had been attracted to two seemingly conflicting sets of ideas. He was deeply drawn to the Jodo Shinshu (True Pure Land) sect within Japanese Buddhism — often known simply as ‘Shin Buddhism’. He was also enthralled by Freudian psychoanalysis. In both systems, the concepts fascinated him. Yet what really struck Kosawa, a life-long fan of heroic biography, were the lives and deeds of what seemed to him to be the exemplary people involved.

Freud advised Kosawa to find a local girlfriend to bring his German up to speed

As a schoolboy, Kosawa had idolised both Shin Buddhism’s 13th-century founder, Shinran, and a modern proponent, the Shin priest Jokan Chikazumi. Chikazumi befriended Kosawa and became a teacher and role model to him. Nevertheless, while studying medicine at Tohoku Imperial University a few years later, Kosawa’s focus shifted to Freud. In a personal letter, written in faltering and oddly romantic German, he credited Freud with seeing into the human heart as clearly as he and his fellow students had learned to observe cells under a microscope. By comparison, Kosawa’s professor at Tohoku cut an unimpressive figure. In 1932, the young student begged money from an elder brother, left his professor behind (he was told never to come back) and set off for Europe to meet Freud face to face.

He didn’t receive quite the reception he’d hoped for. Meeting the elderly Freud at the famous house at Berggasse 19 in Vienna, a Japanese friend had to interpret for him. Freud himself advised Kosawa to find a local girlfriend to bring his German up to speed.

Language was not the only thing separating the two men. As far as the philosophical and religious implications of psychoanalysis were concerned, Freud strenuously disagreed with both Kosawa and with another major pioneer of psychoanalysis in Asia at the time, Girindrasekhar Bose in Calcutta. With only a couple of notable exceptions, the Freud circle treated religion as a purely psychodynamic and social phenomenon, reducible to inner drives and conflicts. They made their camp in the now-familiar territory of faith as wish-fulfillment, avoidance of reality, a means of keeping a lid on society, and the locus of a great deal of obsessive-compulsive behaviour.

For Bose and Kosawa, this merely served to highlight Freud’s parochialism: his lack of experience with non-European cultures and patients. As a matter of fact, Kosawa agreed with his hero that religion was connected with guilt. He just thought it involved guilt of a different type. Freud said that religion derived (both in historical time and in the life of each individual) from the need to assuage one’s fear of a father figure: really, it was a kind of ‘deferred obedience’. Kosawa hoped to persuade Freud that this placatory impulse gave rise to an inadequate religion, and that another sort of guilt was far more important.

He offered Freud a simple illustration. Imagine that a child drops a plate in the presence of his parents. When he seeks forgiveness from his father, the child is rebuffed. He experiences a pang of emotion linked both to fear of impending punishment and to anger and resentment at his father for his harsh reaction. This, according to Kosawa, approximates Freud’s understanding of guilt in the religious context. But then the child asks the mother for forgiveness — and receives it. The mother takes the child’s fearful and rebellious guilt and alchemises it into a ‘reparative guilt’: an overwhelming response to total, unconditional forgiveness. This latter reaction was, for Kosawa, a truly ‘religious state of mind’ and he saw it as the core of his own Shin tradition. Freud appeared unmoved, however. ‘I have received and read your essay and will save it,’ he wrote rather distantly. ‘You do not seem to intend to use it immediately.’ There is no evidence that he gave it another thought.

Despite the master’s rejection, Kosawa was still committed to his idea of reparative guilt more than 30 years later, when Harumi Setouchi (as Jakucho then was) knocked on his door. Oddly, they never talked about religion; Setouchi wasn’t interested in it yet, and Kosawa rarely allowed religious talk into the consulting room. Nevertheless, Shin Buddhism had permeated his therapeutic approach. Rather than attempt to mix the oil and water of Buddhism and psychoanalysis at a conceptual level, he sought, as he told another of his clients, to ‘do psychoanalysis in the spirit of Shinran’.

What did this mean in practice? For Setouchi, it meant that ordinary gestures and moments became infused with surprising power. Her face breaks into the biggest smile of our meeting as she recalls ‘a lovely, a truly lovely man’. ‘He was wonderful, so gentle,’ she explains. ‘He guided me into the parlour area of his house and, after listening to me talk for a little while, he asked me to lie back on the couch with my eyes closed while he sat just behind my head.’

Very soon, she felt sufficiently at ease to go along with Kosawa’s version of free association. ‘Now that your eyes are closed,’ he told her, ‘you’ll be seeing images floating up in front of you. I want you just to name each one as it appears. As though you’re on a train looking out of the window, watching the scenery pass before you.’

Setouchi described various phallic objects to him, suggestive of man-trouble and a hot, possibly violent temperament. The details are not for the prudish, but she insists that at the time she spoke it all effortlessly, and felt immeasurably lighter at the end even of that first session.

‘When people are suffering, when they have some kind of complex, or when they’re lonely, they need someone to notice them’

What’s more, every time he showed Setouchi to the door after an analysis, Kosawa paid her a compliment. I’m happy to pass over this detail when she first mentions it, but she keeps returning to it, beaming, insisting. On one occasion it was the pattern on her kimono; another time it was her coat. ‘He never commented on my looks, though,’ she says with a chuckle. It was all part of the treatment: an unprecedented unburdening followed by the last-minute lift of a well-directed kind word. Nothing like either of these things was on offer anywhere else in her life.

‘To someone who’s suffering, the importance of that just can’t be exaggerated,’ she tells me. ‘When people come to me for help now, I listen to them and at the end I always find some little thing to compliment them on. And you should see them, they derive so much energy from that. When people are suffering, when they have some kind of complex, or when they’re lonely, they need someone to notice them, simply to recognise them. So when someone who’s in real trouble comes to me now, I think to myself, “What was it that Kosawa did for me?” And I try to emulate that. I try to do exactly that — although now it’s become part of my own style.’

Today, Setouchi has countless fans in Japan. They come to pay tribute and seek help in person, crowding into her hugely over-subscribed houwa (Buddhist talks) and filling YouTube with clips of her speeches. Yet her time with Kosawa is almost unknown. How might her admirers react if they realised that this legendary spiritual leader, whether in receptive mode or in full lyrical flow, is all the while channelling Japan’s first psychoanalyst, himself a modern incarnation of a rival religious tradition?

Kosawa was at once slightly behind his times and radically ahead of them. In the Japan of his youth, there had been a considerable appetite for ideas and practices that cut across religion, medicine, and science. Then, as now, such ideas tended to seem especially pertinent to the various anxieties of the ‘modern’ world (we’ve been modern for a long time). And then, as now, there were fears that they were muddying and contaminating the hard-won insights of scientific rationality.

Early-20th-century Japan was streaking ahead of the rest of Asia, modernising its politics, commerce, transport, industry, science, education, and military. Against this backdrop, traditional Japanese faith had become something of an embarrassment. Many felt that the powerful Buddhist establishment had acquiesced in — and profited from — centuries of stagnation. Only now was the nation clawing its way back.

Nevertheless, there were thinkers who saw a space for a rational interpretation of religion. They embarked on a radical process of reinvention, sifting the metaphysical, ethical and psychological wheat from the superstitious chaff of Japan’s spiritual inheritance. What emerged looked a lot like the ‘rationalised’ religion that was becoming popular elsewhere in Asia and the West. Modern science was to be heartily embraced, but its scope was restricted: it applied only to a phenomenal world, one whose supra-phenomenal source was more amenable to religious approaches.

In India, this kind of outlook came to be associated with, among others, Swami Vivekananda, whose rather idiosyncratic ideas were rapturously accepted as ‘Hinduism’ at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. In Japan, much of the running was made by Shin Buddhists such as Enryo Inoue, who recognised the modern promise in Shinran’s view of the human condition.

Disillusioned with his own shortcomings as a monk, Shinran had concluded that human frailty is such that salvation cannot lie primarily in study or ritual — or indeed, in any self-generated activity. He contrasted the idea of jiriki (self-power) and tariki (other-power). A fundamental recognition of your own weakness, he believed, can over time propel you to entrust yourself and your fate to that formless ‘other-power’ — embodied, in Shinran’s tradition, in the celestial Buddha, Amida.

For Setouchi, this makes sense. She’s wryly critical of Shin Buddhism — ‘It’s convenient, isn’t it?’ she tells me. ‘Whatever you’ve done, you just call on Amida, and he’ll come to take you away to his Pure Land.’ Her own heavily ritualised Tendai tradition, it’s worth noting, is the one on which Shinran and other 13th-century Buddhist rebels, including Zen’s Dogen, turned their backs.

Even so, when she lost her own power of judgment, she gained an immediate and unforgettable insight into the limited nature of self-power. ‘I’d always thought that it was me making my way in this world,’ she tells me, ‘until I went to Kosawa’s house. I’d become a novelist because I had talent; my books sold because I had talent — plus a bit of luck. That’s not how I see it any more. There’s no one born into this world because they decided they would be. You’re not born, you’re born.’

This is where Japanese has the edge over English. You can say ‘to be born’ using at least two different forms of the same verb, with radically divergent meanings. Umareru is the commonly used form, creating the sense of ‘to be born’ that we’re all familiar with. Umaresaserareru, on the other hand, is the causative passive: it has the sense of ‘being made to be born by something’, ‘being caused to be born’. I don’t mean the proximate cause — the hours of unforgettable agony on the part of your mother, say (there’s yet another form for that) — but an altogether more encompassing sense of cause. And that’s how Setouchi uses the word: ‘umaresaserareru… nanika ni’ — ‘you are born… by something’.

Buddhism can give the impression that, with enough meditation or prayer, mental health problems will simply go away

Setouchi’s gentle scorn for Shin Buddhism notwithstanding, she sees this nanika, this ‘something’, as closely linked to the other-power that meant so much to Shinran and to Kosawa. And if you’ll bear with me for one more bit of vocab, both Setouchi and another former client of Kosawa have emphasised ikiru vs ikasareru. Ikiru means ‘to live’; ikasareru means something like ‘to be lived’, ‘to be allowed to live’, even ‘to be maintained in existence’ — you are being lived from the outside.

The force of these causative passive forms, which for Setouchi are closer to the truth of the situation than our common active forms, might become viscerally apparent to us in times of distress. ‘We put our hands together, don’t we,’ she remarks. ‘Strange that we do that, isn’t it?’ And perhaps this instinct needn’t only be a Freudian regression to childish father-appeasement. Perhaps it can also provide a glimpse of that elusive umasaserareru/ikasareru.

Setouchi’s Buddhism isn’t a reductive ‘psychologised’ affair, by any means. She took the vows to deepen her intellect and writing, not to surrender either, and she complains that visitors nowadays see only a Buddhist nun and overlook the still highly regarded, Tanizaki Prize-winning novelist. All the same, her own experiences and teaching compel her to take psychology seriously.

An overly psychologised spirituality has obvious perils. There can be isolation or confusion when the community element of religion is effaced. Meaning and nuance are lost when necessarily complex ideas are re-packaged as simple, folksy pop psychology, and ‘spirituality’ becomes just a lofty word for having emotions. Religious commentators learn to dodge reasonable questions about whether and where they shift between metaphor, sentiment and claims about literal truth.

Yet psychologically naive spirituality can be destructive in its own way. Buddhism’s ‘no-self’ insight, like the contrast between ‘false’ and ‘true’ selves sometimes found in Christian teaching, can give the impression that, with enough meditation or prayer, mental health problems will simply go away. Very often the reverse is true. Meditation in particular can show you things that you really ought to take to a psychotherapist or psychiatrist, or perhaps work through, painfully and embarrassingly, with your family.

That brings us to what might be the most useful role for psychology in religion. It offers perspective that stands outside religion’s enticing, evocative conceptual networks: it can show us when our talk of humility, surrender and dismantling the ego are really masking, perhaps even facilitating, their polar opposites — despite our best intentions.

Such might be the fruit of the ongoing dialogue between psychoanalysis and religion. What Kosawa thought of as the ‘false religion’ central to Freud’s (mis)conception remains an occupational hazard in any religious life. Psychoanalysis — together with the newer systems and practices that it helped to propagate — has the potential to offer some unvarnished, barely palatable home truths now and again. Good psychology might end up being the tariki to your jiriki – the ‘other’ to your ‘self’ – as it once was for Jakucho Setouchi.