In September 1945, a month after the foreign ministers of the Soviet Union, Great Britain and the United States issued the Charter of the Nuremberg Trials, the chief US prosecutor, Robert Jackson, wrote an article for The New York Times Magazine to explain the impending proceedings to the US public. In ‘The Worst Crime of All’, he justified why aggressive wars were the charter’s supreme crime: because all others – crimes against humanity and war crimes – derived from the German invasion. Appearing a month after the US dropped two atomic bombs on Japanese cities, the article drew a further, terrible conclusion: ‘If there are to be future wars we have got to win them’ by ‘being better killers, by killing more and killing more quickly than the enemy, by killing with less risk to ourselves.’

In elaborating this argument, Jackson advocated violating the legally established ‘principle of distinction’ between combatants and noncombatants, by casting warfare as conflict between peoples rather than military forces: ‘For the fact is obvious that modern war has become more and more a struggle between whole populations, not between armies alone. The issue is which shall be subjugated and which will survive.’ Consequently, it was necessary in future wars ‘to kill and maim the enemy and to destroy all that shelters him and all that he lives by not only in the field but at home.’ Killing the enemy’s civilians until they surrendered was the strategy – as the unmentioned cases of Hiroshima and Nagasaki indicated. The Nazis, by contrast, had murdered civilians ‘for no military purpose’, he later said during the Nuremberg Trials.

Jackson’s approach proved to be fatally prophetic. Ever since, governments of most stripes countenance inflicting enemy civilian casualties rather than endangering their military forces. Bombing enemies into submission – conceived as entire societies – has been the preferred means, from the US flattening of North Korea in the early 1950s, and later in Vietnam, and the Russian shelling of Grozny, Chechnya, in the 1990s, to the serial Israeli attacks on Gaza, the Syrian government’s barrel-bombing of Aleppo and other localities, and the Saudi-led destruction of Yemen. While more accurate than shelling and saturation bombing, continuous US drone strikes also causes civilian deaths. Together, these actions have killed millions. Trumping them all is the largest post-Second World War civilian casualty case: the some 45 million ordinary Chinese who perished in the Great Leap Forward famine between 1958 and 1962. But who remembers these people and their suffering besides their families and some academics? They’re excluded from the contemporary image of authentic victimhood because they aren’t victims of genocide.

The crystallisation of ‘the victim’ since 1945 comprised several elements based more on selective forgetting than inclusive remembering. After the First World War, the experiences of Armenian and Russian refugees in particular featured in Western humanitarian campaigns as victims worthy of empathy and emergency mobilisation. But after the Second World War, the hundreds of thousands of displaced persons languishing in camps couldn’t be accorded the same status because most refugees were now ethnic Germans expelled from eastern and central Europe with Allied consent.

Second, Allied bombing killed almost a million German and Japanese civilians: again, enemy civilians couldn’t be iconic victims. Although Germans and Japanese militaries had started the practice of bombing undefended cities, the Allies perfected it. This is why, at Nuremberg, Germans weren’t indicted for their aerial bombing campaigns.

Third, states distinguish between ‘military necessity’ – measures taken to achieve military aims not prohibited by international law – and emergency domestic security on the one hand, and genocidal intention on the other, although the same number of civilians might be affected. Consequently, while civilians are killed in smaller numbers in ‘proportionate’ responses to perceived security threats, their deaths accumulate over time as entirely legal, ‘business as usual’ actions. Such casualties can’t be seen as iconic victims if states engage in international and non-international armed conflict on the terms they prefer. In other words, these civilian deaths don’t ‘shock the conscience of mankind’, to use the archaic phrase that recurs in international humanitarian legal instruments.

If Jackson was prophetic about the shape of postwar conflict, he was wrong about the worst crime. By the late 1940s, genocide replaced aggressive warfare as the threshold that ‘shocked the conscience of mankind’. And genocide’s archetype was the Holocaust. States couldn’t agree on defining aggressive warfare, while Holocaust victims were becoming increasingly visible after serial trials of German perpetrators. The historian Deborah Lipstadt explained how in 2017:

The Holocaust was something entirely different. It was an organised programme with the goal of wiping out a specific people. Jews did not have to do anything to be perceived as worthy of being murdered. Old people who had to be wheeled to the deportation trains and babies who had to be carried were all to be killed. The point was not, as in occupied countries, to get rid of people because they might mount a resistance to Nazism, but to get rid of Jews because they were Jews.

Lipstadt advanced this argument in part to remind the then US president Donald Trump not to trivialise the Holocaust, in part to counter antisemites who contended that Jews provoked Germans and were thus co-responsible for their fate. Its consequence is to separate the Holocaust from other instances of civilian destruction: it’s not ‘just one in a long string of inhumanities’, as Lipstadt and many others have long insisted. As a massive hate crime against innocent victims – meaning that they weren’t involved in military conflict, not killed by military necessity – the Holocaust shaped the ideal victim type.

This distinction between innocent victims whose suffering ‘shocks the conscience of mankind’ and expendable victims who are largely forgotten has Christian and Jewish theological roots. The Christ figure voluntarily takes on the sins of humanity in an act of self-sacrifice, his innocence vouchsafing its efficacy. The New Testament interpretation of the crucifixion borrowed liberally from Jewish traditions, as in Paul’s depiction of Jesus as the unspoiled ‘paschal lamb’ sacrificed at Passover.

In Judaism, Jewish victims are called Kedoshim, literally ‘holy ones’: martyrs of the Jewish people because they were murdered solely on the grounds of their religion, not for anything they have done. As martyrs, the dead were sacrificed for membership of their group, targeted because of their despised identity, bereft of political agency. This victim is innocent and thus depoliticised, meaning uninvolved, even vicariously, in armed conflict. By voluntarily accepting their fate and resisting the temptation to convert – during Christian pogroms in the Middle Ages, for instance – Jewish victims died Al Kiddush Ha-Shem, literally ‘for the sanctification of the divine name’. In the case of the Holocaust, they are the ‘6 million Kedoshim’. Rabbis in the Warsaw Ghetto paraphrased the medieval Jewish theologian Maimonides to rule that a Jew who was killed ‘simply because he is a Jew, is called Kaddosh’.

Their innocence is also a function of their murderer’s motivation: ‘the longest hatred’, as the historian Robert Wistrich described antisemitism in 1991. In this rendering, antisemitism possesses ontological status as groundless antipathy towards Jews. Exemplifying this view, the historians Brendan Simms and Charlie Laderman in 2016 referred to antisemitism as a ‘virus’ that takes ‘so many forms … that it may be impossible ever to eradicate it.’ Whatever its garb, antisemitism is posited as an independent and active force in history, irrational hatred incarnate, adapting itself to time and place; Christians did the hating in the past, then fascists, and now – many contend – it’s Muslims and their naive fellow-travellers, Leftist anti-Zionists.

The image of the largely agentless and innocent Jewish victim represents the ‘ideal’ victim: that socially constructed status by which sympathy and legitimacy are conferred on certain objects of violence and not on others. Because of the Holocaust memory’s omnipresence, its Jewish victims represent the archetypal and universal form of this status. This status becomes what the writer Alex Cocotas in 2017 called a ‘sacred altar’ that ‘foster[s] identification with victimhood’, even though – or perhaps because – most people are likely to be perpetrators rather than victims because they aren’t members of minorities.

Whether Jewish or Christian, or both, the image of the exemplary victim has proven irresistible to those seeking recognition as innocent victims of persecutions who deserve protection and/or compensation. Victims of various conflicts routinely construct themselves as Jews: killed for their identity rather than for their deeds, likewise virtuous martyrs.

The most influential approach to victim-construction is the ‘scapegoating’ mechanism

Sometimes this recognition is easy. ‘Who if not the Jewish people should have a particular understanding for the persecution of the biblical Yazidi minority?’ said Deidre Berger, director of the American Jewish Committee in Berlin, of the Iraqi minority attacked by Daesh (ISIS). The Armenian Genocide Museum-institute in Yerevan routinely describes the Ottoman Armenian victims as ‘holy martyrs’ and in 2015, a century after the genocide began, the Armenian Apostolic Church canonised them as ‘saints’. They were innocent victims of Turkish racism and hate, while Turkish authorities insist that wartime disturbances caused casualties on both sides.

They have a point: the campaign against Ottoman Armenians began with a military emergency occasioned by the invasion of the Ottoman empire by Allied forces in the east and south, in which some Armenians participated. But Turkish diplomats never ask why securing battle zones entailed executing Armenian elites and marching women, children and the elderly into the desert to perish. A wealth of evidence attests to the government’s intention to once and for all solve the ‘Armenian problem’ to achieve permanent security.

Instead of understanding such pernicious political calculations made by paranoid states, we fixate on the unpolitical victim. Understandable empathy replaces necessary analysis. The former shapes Holocaust and human rights education with its emphasis on the depoliticised victim. Typically, such education programmes classify a group as victims when they’re placed beyond the ‘boundaries of the universe of obligation’: they aren’t members of ‘the circle of individuals and groups toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for amends.’ The social dynamic determining such a hierarchy of caring is auto-generated hatred: hatred that’s not a reaction to attributes of the hated group but a product of the hater’s psychodrama. It’s internally generated rather than arising in dynamic relationships with the outside world.

The most influential approach to victim-construction is the ‘scapegoating’ mechanism. In 1939, the literary scholar Kenneth Burke formulated this mechanism of victim-construction in analysing Adolf Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf (1925). Drawing on Sigmund Freud’s notion that civilisational order requires repression and thus produces frustration, Burke saw in the operation of Nazi ideology a ‘vicarious victimage’ purification ritual: a subject projects his guilt and inadequacies on to an external vessel, the scapegoat. In the Hebrew Bible, God tells Moses to instruct his brother Aaron to take two goats; one will be presented to the Lord, the other ‘marked for Azazel’, that is, for removal (the scapegoat). As verses 21 and 22 of Leviticus depict the drama, the goat takes on and carries off the community’s sins, further purging and purifying it by the sacrifice of the other goat. Its destruction serves as a sacrificial offering, leading to the community’s ‘symbolic rebirth’.

Burke was writing two years before the German mass shootings of Soviet Jews and the operation of the death camps. Even so, by then he claimed to understand the genocidal logic of Nazi victimage:

The ‘Aryan’ is ‘constructive’; the Jew is ‘destructive’; and the ‘Aryan’, to continue his construction, must destroy the Jewish destruction. The Aryan, as the vessel of love, must hate the Jewish hate.

The French writer Alain Finkielkraut echoed this view when, referring to Nazi persecution of Jews, he wrote in The Imaginary Jew (1980) that ‘Scapegoats from time immemorial were rudely cast into an unrecognisable world, subjected to total war and treated as the absolute enemy.’ Such an enemy was not merely to be ghettoised, but to be completely exterminated.

Although Freudian models of repressed psychodynamic conflict have fallen out of favour in social psychology, the scapegoating notion remains popular as a metaphor. For instance, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum explains in its online entry on antisemitism that: ‘In more desperate times, Jews became scapegoats for many problems people suffered.’ It thereby continues venerable theories popular from the 1930s about social frustration and the displacement of aggression onto hapless minorities. It’s significant that the goat is innocent, as is the human scapegoat; it’s the agentless victim of a community’s mythic drama of redemption, an object of pent-up frustration.

The problem in this view of victim-construction is that it’s religious rather than political. It’s a secularised theology about the origins of evil: groups are victims of prejudice that arise within evil people. Since the Holocaust, the analogical drama has been populated by pantomime villains (Nazis) and victims (Jews). This disavowed theological view of conflict stimulates powerful affects in Western liberal internationalists, who feel they must ‘do something’ when witnessing wickedness abroad. The former US ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, embodies this subjectivity most acutely. Youthful encounters with the terrible fate of Anne Frank and the Holocaust drove her resolve to personally make the US a global force to realise the maxim of ‘never again’, thereby implicating Holocaust memory in a new civilising mission. In Libya in 2011, she and the French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy – who lobbied his president to bomb Libyan forces – saw once again the Holocaust drama of ‘innocent victims’ and ‘evil perpetrators’ unfolding before their eyes; it demanded their intervention.

When that intervention failed – in fact, its destruction of the Libyan state unleashed far more violence than it aimed to prevent – Power blamed the Libyan (non)victims. ‘Whatever our sincerity,’ she wrote in her exculpatory memoir of the Libya debacle, ‘we could hardly expect to have a crystal ball when it came to accurately predicting outcomes in places where the culture was not our own.’ Power was conceding that the US couldn’t be expected to understand the countries it bombed. The Libyan crisis was more complicated – more political – than her pantomime moralism could grasp.

The discourse of innocent victimhood empowers powerful activists to generate more violence and kill more innocent victims in the name of saving the world from violence against innocent victims. The salience of the deep structuring distinction between exemplary and invisible victims is exemplified by Power’s silence on the drone strikes favoured by her former boss, the former US president Barack Obama. Nearly 10 per cent of the 3,797 people they killed in the 542 strikes he authorised were civilians: these were entirely legal collateral deaths. They died for the good cause of freedom.

Why does mass violence need to resemble the Holocaust to be recognisable as genocide?

We know that the principle of civilian immunity is the presumption of civilian innocence. Military thinkers and international lawyers have wrestled with the conundrum of observing that 20th-century warfare was total, whether in enlisting entire populations in two world wars or in internal armed conflict such as in civil wars. Total warfare, they suggest, means that factory workers and their families contribute to the war effort as much as soldiers on the front: they’re not so innocent, hence they’re legitimate targets. To insist on the tidy distinction between combatants and civilians is outmoded, they conclude. That’s why Jackson told US readers in 1945 to be prepared to kill as many enemy civilians as necessary in the incipient Cold War.

But, if civilians are not immune, they’re presumed guilty by association with enemy combatants – including neutral humanitarian personnel providing medical assistance to designated terrorists, not to mention so-called ‘human shields’. Then we verge on the mental world of genocide: entire peoples as enemies whose members are collectively guilty, or at least expendable. Is it to conceal this murderous assumption in military strategy and international law that civilians need to resemble Holocaust victims to ‘shock the conscience of mankind’? And, furthermore, is that why such mass violence needs to resemble the Holocaust to be recognisable as genocide?

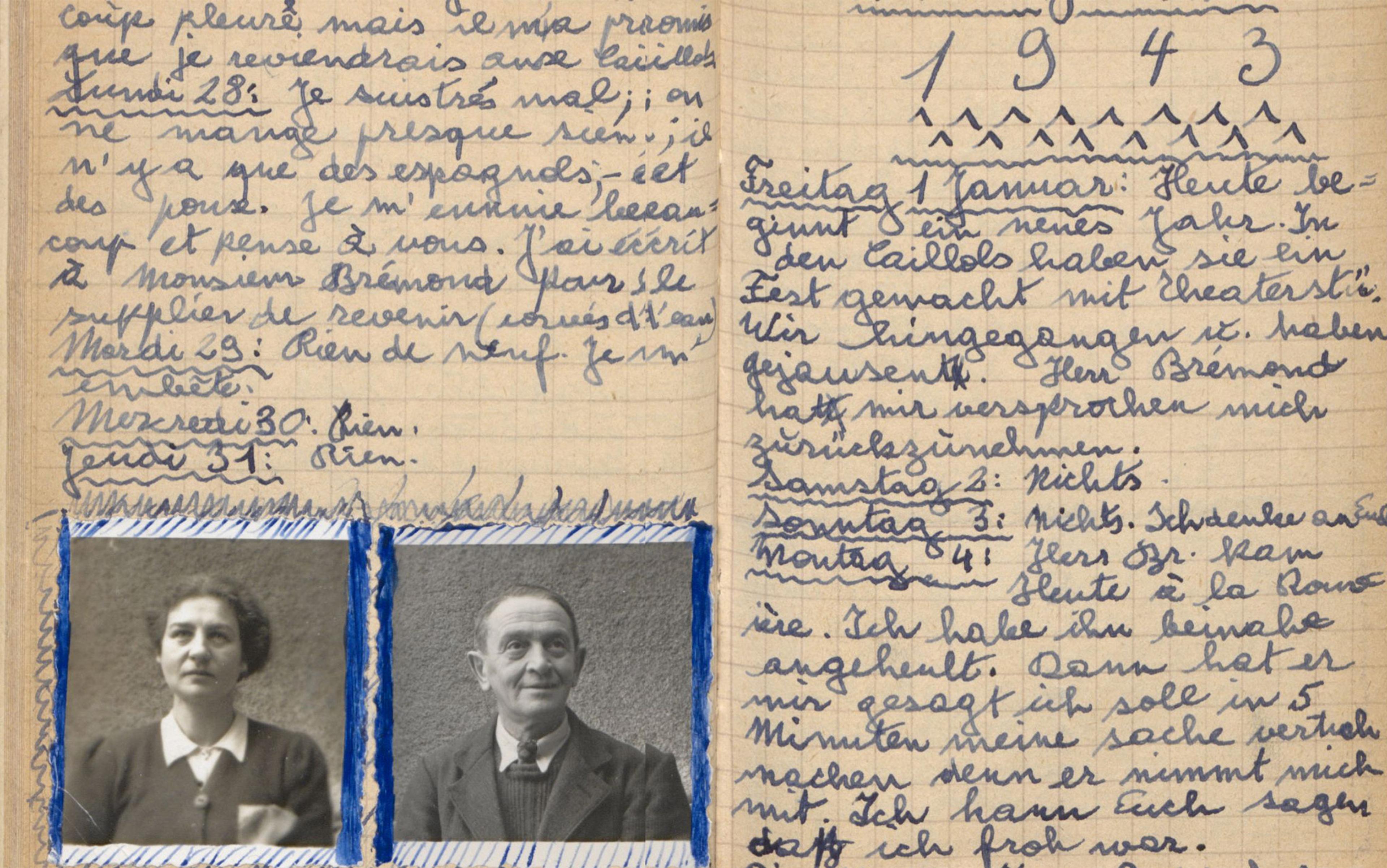

Family Photo 1 (2015) by Murad Subay. Courtesy and © the artist

Artists operating outside these assumptions offer reminders about unseen victims. Murad Subay’s Family Photo 1 (2015), shown above, depicts a small bombed-out room of a cinderblock house in Sana’a, Yemen. On the back wall, Subay has painted a picture of a family posed in the well-known, formal pose: parents standing, beside them two children, an infant cradled in the mother’s arm. The image is slightly tilted from the blast. An oversize raven is perched ominously on the picture frame, peering down at them to signal their awful fate. Family Photo 1 is among 18 images in Subay’s ‘Ruins’ series (or ‘campaigns,’ as Subay calls his collective, consciousness-raising undertakings) launched in May 2015 in the Bani Hawwat area of the Sana’a Governorate, where, he writes, ‘the air strikes destroyed more than seven houses there and killed 27 civilians, including 15 children’.

Born in 1987, Subay has been documenting the activism and suffering of his Yemeni compatriots since the 2011 Arab Spring revolution, and especially the civil and Saudi-Iranian proxy war that began in 2014. His Faces of War Selfie Mural, mounted in Paris in December 2020, commemorates ‘more than 230,000 dead, since 2014’. Fewer people than you think outside Yemen realise that Saudi forces have been pounding the country with shells and missiles made in the US and the UK. While sometimes mentioned as among the world’s gravest humanitarian catastrophes, the plight of Yemen’s civilians rarely ‘shocks the conscience of mankind’.

The multifaceted conflict in Yemen is illegible according to Holocaust criteria that search for the binary of ideal victims and wholly evil perpetrators but not the typical conflicts of the postwar world: namely, those involving multiple, internal and external state and private actors, driven by predatory political economies of semi-organised criminality as well as geopolitical security. As a small gesture to call these people into consciousness, I chose Subay’s haunting Family Photo 1 for the cover of my book, The Problems of Genocide (2021). They should not be forgotten. Their memory should provoke us to think again about seeing all civilian victims, and reflect on the causes of their suffering.