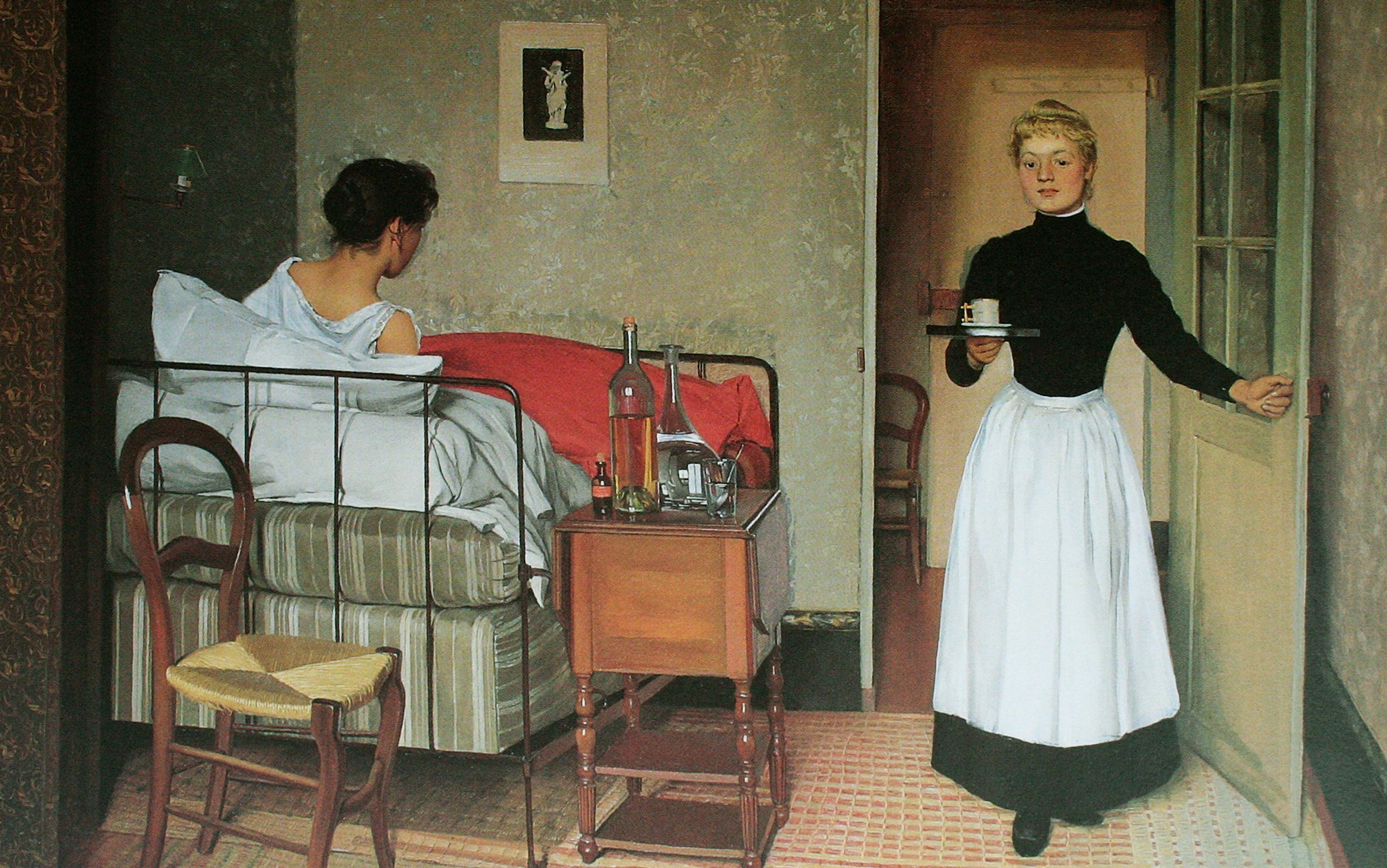

In 1877, the neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell of Philadelphia published a therapeutic guidebook called Fat and Blood. In its pages, he laid out a comprehensive treatment programme for patients

of a class well known to every physician, – nervous women, who, as a rule, are thin, and lack blood. Most of them have … passed through many hands and been treated in turn for gastric, spinal, or uterine troubles, but who remained at the end as at the beginning, invalids.

Mitchell was not alone in his disdain for these patients, whose illness had no cause detectable with the tools of the era. To him, they represented a particular kind of moral menace, a refusal to perform one’s gendered duties, which could infect all of society. With unselfconsciously hysterical rhetoric, Mitchell stoked fear that the United States’ disciplined, masculine-bodied economy would be engulfed by hysteria. The menace had to be contained.

The treatment he described, the rest cure, was correspondingly extreme. Patients were confined to bed for at least six weeks, at first not allowed to read, visit the bathroom or even roll over unaided. They consumed heroic amounts of milk, about two quarts a day, gradually supplemented with as much food as the patient could eat (and probably more: Mitchell advised that complaints of over-fullness be disregarded). Finally, they began strengthening exercises and were gradually allowed to walk. ‘A large number of women,’ he claimed, ‘have been rescued by my treatment after all else had failed, and … have ever since enjoyed the most absolute and useful vigour of mind and body.’

Mitchell offered a scientific rationale for the cure’s effectiveness: his patients were deficient in blood, and dramatic weight gain restored the ‘amount and quality’ of that substance. The leading neurologist of his day, he was renowned for his treatment of nerve injuries during the Civil War. Beneath the rest cure’s sketchy science was the cardinal principle of medicine that reigned from antiquity until Mitchell learned it in school: that the body can often heal itself if you give it rest and food. He reported results ‘so remarkable that the process of repair might well have been called a renewal of life’.

The rest cure is remembered today for its coercive denial of women’s agency, mostly by way of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ (1892), which describes the isolation, despair and madness that the treatment could provoke. In case of any doubt as to her story’s moral, Gilman later explained that she wrote it for Mitchell, because her own encounter with the rest cure had driven her to the brink of insanity. She assailed a medical system that took the feebleness and inferiority of women as its premise and then reduced women to that state with oppressive pseudotherapies.

This sensitivity to systemic injustices, inflicted on spurious biological grounds, didn’t at all extend to Gilman’s views on race. While she asserted the autonomy of her white, female body, she wrote repeatedly about the inherent inferiority of nonwhite people. In this way, she wielded her pen to protect Mitchell’s order, where the sick white woman becomes plump and fertile – fed, no doubt, by the toil of those supposedly inferior races, whose illness or exhaustion was not the subject of her literature. As though having one’s suffering taken seriously were a zero-sum game.

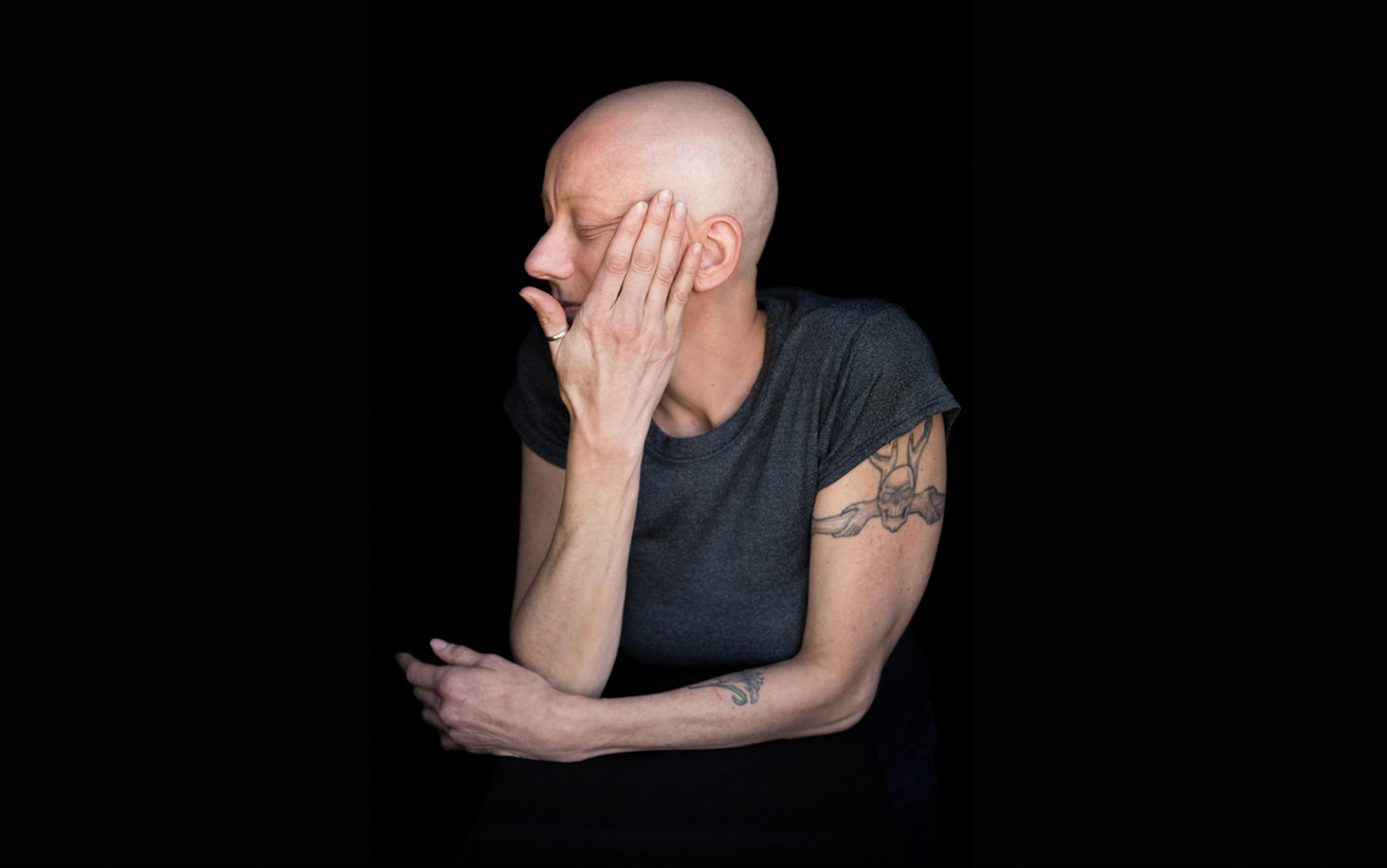

I am spending a day in bed. While I ‘rest’, everything I should be writing curls out my ears like smoke. At this stage, I am probably collapsed on a sagging futon in my boyfriend’s house. We have a discussion about what will happen if I remain unable to cook or clean for myself. A growing list of small tasks that I’m pathetically incapable of completing scrolls on the backs of my eyelids. I want to work, not just because there’s no such thing as sick leave for adjunct professors, but because I will go crazy if I can’t engage in some kind of meaningful interface with the outside world. I have lost traction, like a broken water-wheel, with time, the only real resource I have, gushing past.

The doctors I consult find it interesting to pose a chicken-or-egg question regarding disorders of body and mind: ‘Do you realise that depression can cause these symptoms?’ Many people suffer from mental illnesses with complex physical manifestations. However, to embrace the poultry metaphor, I am the chicken coop and I have a detailed record of which came first. In the midst of an ordinary period marked by no unusual emotional vagaries, I lost the ability to hold up a book or walk more than a few yards without resting, though I developed workarounds to take care of myself for as long as I could. It is true that, as pressing buttons on a phone became a source of excruciating pain, I started to feel the animal despair that comes with not knowing when the pain will end. Surely there are depths of the mind that I can’t access. I felt just as sure that the cause of my pain wasn’t in there.

Mitchell’s writing from the 1870s reflects the already-common assumption that patients, especially female patients, might lack the insight to realise that their illnesses are psychological in nature. The rest cure essentially played along with the patients’ delusion until they believed they’d recovered. Later practitioners, however, took more interest in psychological causes, and sought a direct line to the hidden realm that Sigmund Freud termed the unconscious. Whether through hypnosis or dream analysis, they proposed what historians of medicine term a ‘magic bullet’: a simple, fast and scalable solution that targets the root cause of disorder. In psychiatry, insight was supposed to be that magic bullet, revealing to the patient her own repressed psychic trauma.

In my doctor’s office, I recognise that it’s time to defend the truth of my embodied experience

In Freud’s account of ‘Dora’ – a formative case, from 1900, for the theory of psychoanalysis – the patient complained of sexual assault by a family friend. Her parents knew but refused to address the man’s behaviour. This might seem like the smoking gun, the underlying trauma that caused Dora’s hysterical fits. Here’s the problem with the magic bullet: it can’t hit a target that’s not inside the patient. Freud, seeking a deeper origin for Dora’s disturbance, traced it back to her Oedipal desire to have sex with her father. Though Dora removed herself from his care at that point, Freud maintained that she would have been cured had she accepted his findings. His premise, that the solution to the mystery lies in the individual’s unconscious, doesn’t have a track record of fairness and accuracy.

I think about Dora and Freud and Mitchell all the time because I teach these texts to college students in classes on the history of medicine; I am a walking encyclopaedia of the ways in which medical authority has disqualified patients’ experiences of their own bodies and what society does to them. I know the advantage I have, as a white woman with a graduate degree, and also the ways in which that plays into its own set of expectations. In my doctor’s office, I recognise that it’s time to defend the truth of my embodied experience. But I’ve never felt so ill and would prefer it were not real. Every conceivable laboratory test is normal. I want to believe my doctor when he says that nothing is wrong.

My intention to ignore bodily sensations and continue living as I normally would is thwarted by a steady downhill slide. I have to use two feet on the brakes in order to stop my car; the muscles of my jaw, which I had never noticed before, lose the motive power to chew or speak for more than a few minutes. In her memoir The Undying (2019), the American poet Anne Boyer writes about the aftermath of her chemotherapy: ‘The trying of the exhausted is fuel for the machine that keeps running them over in the first place.’ But Boyer had oncologically repurposed mustard gas pumped into her veins. My doctor suggests that I am suffering only from my own misrecognised emotions.

So I consult a psychologist for the first time in my life; after a few visits, she explains that there is no evidence of a clinical disorder, no grounds for taking the habit-forming antidepressants that my GP has prescribed. I rest enough to drive my body through a day, though sleep hardly makes a difference, until nothing helps anymore, and I go under.

Hysteria, notorious as a diagnosis that pathologised female sexuality and noncompliance, was only one face of the new ‘American nervousness’ that swept the country in the late 19th century. The fact that men were equally affected led physicians to seek a cause not in the female organs, but in the nervous system, whose disarray they termed ‘neurasthenia’. By the 1870s, both men and women, particularly of the urban white-collar classes, found the unprecedented stresses of capitalist modernity exhausting their nerves.

The way that doctors interpreted and treated their patients’ turmoil was shaped by the current scientific understanding of gender differences. While a vast array of practitioners pushed a bewildering range of therapies, Mitchell produced a notably gender-polarised system: neurasthenic men had to ‘man up’, restoring their zest for imperial conquest and domination through rugged expeditions to the western frontier. Women had to be isolated and immobilised, forced to respect their limitations. Mitchell was obsessed with maintaining this dichotomy precisely because its collapse was visible on the horizon. Many of his female patients were novelists, critics or teachers, doing the same work as modern men and suffering the same consequences.

Mitchell was not alone in defending the uniquely white, masculine status of white-collar work that basically consisted of thinking, reading, writing and talking. Psychologists and educators valorised ‘brain work’, portraying it as somehow more dangerous and heroic than physical labour such as mining coal, or reproductive labour – birthing a child, running a household. Even more than gender difference, racial difference preoccupied them. Medical authorities embraced the eugenic belief that certain kinds of people were born incapable of sophisticated thought – immigrants, African Americans, anyone below ‘Nordic males’ on the racial hierarchy. Women of colour, in this interlocking scheme, were doubly reduced to pure biology. The African-American writer Julia Collins, who decried this false determinism of blood, might have died from tuberculosis in 1865 in part because doctors didn’t believe it merited the same treatment in Black patients as in white ones. Asylum superintendents exhibited tragic cases that showed the consequences of stepping beyond the limits of one’s nervous system. They identified ‘women’s education’ as a leading cause of neurasthenia.

My boyfriend drives me to an appointment with the neurologist. How lucky am I to know someone who will do this caring work for me? But luck is fickle. Needing his help is freaking me out. Over my three decades of life, I’ve absorbed the quite ableist imperative to avoid relying on others, who could perceive this as attention-seeking or burdensome. That’s why a clinical diagnosis would be useful, certifying that I really deserve help. That’s why it’s important to keep doing tests, and to ignore the accumulating bills.

The neurologist, a middle-aged man who treats people with gruelling illnesses such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s, expects normal results from this test because he has already decided that my symptoms are psychogenic. Freud was a neurologist. I expect normal results because I know that I’m being punished for something.

I even know what it is: I have, in my capacity as a historian, strongly suggested that reason and the scientific method have limits. I’m on record stating that medicine will never achieve its dream of rendering the body and mind fully transparent and manipulable. Moreover, I believe that the dream of total control is inherently misogynistic, and leads physicians to dismiss what they can’t explain. Now I’m sick but I can’t produce objective evidence. I will be told that I’m crazy; this is only fair play.

‘I don’t see anything wrong,’ says the neurologist, while rushing to escape the room. ‘I think this is chronic fatigue syndrome. It’s when people are very tired. They get exercise therapy and see a psychiatrist,’ he explains as he shuts the door. I recognise from context cues that the practitioner has cloaked his verdict of hysteria in a neutral clinical term.

Even the massive literatures of wellness and self-care are infused with the ideology of work

I am the loathed patient with an internet connection. From a perfunctory search back home, I glean that the doctor’s understanding of this diagnosis is 20 years out of date. Medical journals explain that physicians once considered chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) a psychogenic illness treatable with exercise, but it is now regarded as a somatic disorder – myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) – the denial of which is inhumane. In many cases, exercise therapy exacerbated patients’ illness until they were bedridden.

Browsing the online message boards of the CFS/ME community, I see how crucial it is that the doctors whom they trust acknowledge the physical reality of their condition. The patients are versed in immunology and molecular biology, explaining each viable hypothesis to newcomers. Despite the failure of mainstream medicine to listen to them, they still believe that science can solve the mystery that has dominated their lives. They have an important critique of authority, yet also need whatever power it can muster to their cause. Although I can identify, my symptoms don’t meet the diagnostic criteria.

It’s helpful to read positive ideas about rest on these chronic fatigue forums. My custom in the past was to keep moving, ignoring common transitory ailments. The body, like a piece of machinery, sometimes turns back on when you kick it. Even the massive literatures of wellness and self-care are infused with the ideology of work. If you feel bad, it’s because you’re not doing enough. People with rare diseases are celebrated for trying to bio-hack their own cures, because drug companies can’t invest in unprofitable research. And have you tried vitamin D?

Health insurers increasingly enrol customers in surveillance-based wellness programmes that penalise them for resting. No matter how exhausting your work, if you haven’t swiped your card at the gym, or your steps-per-day are down, or your weight is up, you pay a fine. ‘Waist Lines … Rob Bottom Lines’ declared the Journal of Management Policy and Practice in 2013, urging organisations to ‘protect and enhance their biggest asset, human capital’. As Lena Solow reported in 2019, the teacher strike in West Virginia in 2018 was inspired in part by anger about compulsory activity-tracking. For the fifth-lowest teacher salary in the country, teachers had to work on their bodies literally all the time. Perhaps the stated goal, greater productivity, was never really as important as making benefits contingent on biometrics.

The rest cure was also concerned with metrics, carefully logging food intake, weight gain and (non)activity. Patients understood that they were working to get better, a kind of biological labour now equally demanded of healthy people. But if even the rest cure is work, what is actual rest – rest without an expectation of productivity? It feels alarmingly close to death.

I am crying, afraid that I won’t be able to return to work and make minimum credit card payments. ‘You seem very upset,’ the doctor says. ‘Sometimes the mind causes real problems with the body. We call this a conversion disorder,’ he adds with a generous flourish, as though lifting a velvet curtain to reveal the truth.

I don’t need to ask what a conversion disorder is. When the term ‘hysteria’ began to sound antiquated, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980 updated it to something more scientific. As in Freud’s psychoanalysis, resisting the doctor’s explanation is proof that he’s right.

Given a diagnosis of actual hysteria – an artifact from the 19th century that had seemingly hunted me down in the year 2018 – I naturally returned to Fat and Blood, which I had never read very closely before. Mitchell, despite his fundamental mistrust of women, acknowledged that they were subject to the same range of disorders as men, not just self-inflicted hysteria. He further acknowledged that women’s suffering is often wrongly disbelieved, and urged his colleagues not to be ‘too sceptical as to the presence of real causes’. The rest cure was a regular Swiss Army knife: it fixed somatic ailments, soothed psychosomatic cases who put faith in the doctor’s power, and was the perfect punishment for women who were faking it.

Indeed, amid Mitchell’s smug descriptions of ‘thin blooded emotional women, for whom a state of weak health has become a long and, almost I might say, a cherished habit’, there are women with verified somatic disease, and also women whose work and overwork Mitchell judges to be virtuous.

‘[T]hough I have no productive worth,’ she wrote in 1891, ‘I have a certain value as an indestructible quantity’

‘Miss C, an interesting woman, [age] 26’, took a job as a clerk to support her sick mother, before a ‘series of calamities’ led to her collapse. Mitchell approved of this patient because of her exemplary effort to do her filial duty. Illness was not Miss C’s fault; she was forced out into the world. One suspects that Mitchell’s opinion would sour if Miss C clerked because she wanted to. He wouldn’t be consulting with a patient from the class of women who did paid work all their lives out of necessity. Though female empowerment was the furthest thing from her doctor’s mind, the patient reported that the rest cure enabled her to ‘enjoy work, and to do with myself what I like’.

Fat and Blood contains many interlocking layers of misogyny that are of great historical interest. For the first time, I asked the question that desperate people ask: did it work? If modern medicine had nothing to offer, maybe this backward therapy of the 19th century was the best that I could do. In certain ways, the rest cure prefigured today’s governing ideology that equates productivity with human value. That was precisely the ideology that I needed my body to serve once again.

I knew it was bad that I had reached the point of this admission. I don’t believe that our worth is measured by our productivity – but it’s a luxury to assert philosophical dissent from the social discipline stamped into us from birth. Or rather, making that dissent register in the world is its own tremendous labour, which reads as a luxury because it’s not the sort of work we’re supposed to be doing with our limited time and shambling bodies.

Alice James, sister of the American writers William and Henry James, fit Mitchell’s archetype of the idle sick woman, but her diaries reveal an intellect no less capacious than those of her brothers. It was turned towards the paradoxical work of illness. Being sick, she insisted, was not passive or meaningless. Her position outside of normal society, in the grip of chronic pain, led her to write extensively on the ‘significance of experience’, seeking the spiritual and philosophical grounds for living in a body that doesn’t work the way others do. With her diaries, Alice left behind not a virtuous death, but an argument for the irreducible significance of a woman’s life. ‘[T]hough I have no productive worth,’ she wrote in 1891, ‘I have a certain value as an indestructible quantity.’

The problems with undertaking Mitchell’s rest cure in 2018 are obvious – aside from the misogyny, who pays for six weeks of recumbent milk-guzzling? Mitchell’s patients weren’t all rich; some, like Miss C, were downwardly mobile and had already lost wages from illness. How did they cover room, board and individualised therapy? The cost of healthcare in general was lower in the 19th century – tubs of cold water were a leading therapeutic technology. Still, the proper rest cure was a middle- and upper-class domain. For the sick poor, whose illness was blamed on their bad habits, philanthropy and public spending supported a patchwork of sanitariums and visiting nurse services. Like Mitchell’s, these regimens were designed to restore productive bodies using surveillance and force. The velvet gloves were off for sick industrial workers and sharecroppers caught in a system that disdained them and required their labour.

I was set up for a middle-class life but have failed to secure much of the requisite infrastructure. In the gap between school sessions when I should have been freelancing, I would attempt to cure myself at home, living on the emergency savings that double as a retirement fund (like many Americans of my generation, I hope to retire a few months before I die). Even without the bells and whistles of a dedicated 19th-century medical facility, the rest cure, I decided, is a state of mind. With all other possibilities exhausted, the patient accepts the idea of resting as the only path back to a normal life. I was not a good patient, even of my own retrograde therapeutics. I have a powerful aversion to drinking milk. I also have a powerful aversion to lying still in a silent room, the rest cure’s main component. Though I declared a rest cure, I kept trying to work when I felt a little bit better, until I felt bad again. I told myself that I was taking two steps forward and one step back.

Some might blame me for a botched execution, but I think my only error was reading the instructions too closely. Mitchell’s messaging about the reason for rest is inconsistent. He oscillates between the idea of breaking down the patient mentally, to gain psychological control over them, and the prospect of bodily renewal through prolonged immobility. For him as a doctor, the difference was immaterial. For me, as a patient, it’s rather important – I would like to avoid a ‘Yellow Wallpaper’ outcome. I could track signs of physical improvement, but Mitchell coached patients not to trust their own subjective sensations. We all have a Mitchell in our heads now – a suspicion of our own bodies, the fear that it might be psychosomatic, a sense that the moral thing is to push through.

The chronic limitations of the body will be captured using precise tools for appraising and managing human capital

The idea of a ‘cure’ is as comforting as the idea of ‘rest’ is frightening. Mitchell claimed complete and lasting cure for most of his patients. Everyone gains 20 lbs and gets out of bed ruddy and cheerful. Is it too good to be true? Mitchell, along with other neurasthenia gurus, openly embraced the power of suggestion. Yet that power has limits, especially when the structure of our lives and economies is itself pathogenic. The doctrine of positive thinking is fundamentally a doctrine of denying material reality. Maintaining this mind-over-matter delusion requires a certain amount of luxury, which we must simulate with scented bath products and micromeditations.

‘Cure’ took on new certainty and completeness with the advent of 20th-century pharmaceuticals and procedures. A blood test can show that the offending bacteria have been eliminated. We aspire to cure a wide variety of processes, from cancer to addiction, multiple sclerosis to ageing, in the same way. But this will never be certain or complete. Our bodies are constantly falling into disorder, a state described as chronic, as in, we are chronically alive. Figuring out how to continue that way is the goal.

My rest cure allowed me to continue in a way. Through trial and error, I figured out how to manage the body I have; I keep a balance sheet of what I can and can’t do. Also, what I can’t afford: specialists who might have answers but aren’t in-network, tests that aren’t covered by my insurance, time arguing with my insurer over the phone. It’s good to be aware of these metrics, since they determine one’s horizons. ‘It is decidedly indecent to catalogue oneself,’ wrote Alice James, and then capitulated to her century – ‘but I put it down in a scientific spirit.’

In our century, the scientific spirit has gone from cataloguing to data-mining. As employers such as Walmart, Google and Amazon develop in-house health insurance and medical facilities, the chronic limitations of the human body – the fluctuating levels of ability and disability that characterise every life – will be captured using ever-more precise tools for appraising and managing human capital.

Before the conquest of contagious disease and the rise of chronic illness as a multibillion-dollar burden on the US economy, there was the moral panic over ‘chronic pauperism’. The progressive-era economist Richard T Ely called it ‘for the most part a curable disease’. Writing in 1891, he advocated market regulation to incentivise the striving of able-bodied Nordic white people, and eugenics for everybody else. Ely was a liberal, in that he believed capitalism should be reined in before it literally killed the working class, yet these were the terms of its sustainability: groups who gave the lie to the bootstrapping myth had to be sacrificed.

This account is not a satisfying illness narrative, which should move through diagnosis to personal insight, empowerment and recovery. I’ve got none of those things, but I did have months to think about all the carnage that these narrative forms cover up.

The American writer Nafissa Thompson-Spires in 2018 called for writing ‘ugly stories’ – not just about the sort of pain that runs through her life with endometriosis, but stories where narrative itself becomes a series of betrayals that none of us individually can look away from or fix. Instead of wrapping up with my best self-care tips and vitamin regimen, I’ll simply suggest that we are all always on the precipice, if not in the depths, of chronic mystery. Why is it so hard to be sick in a world replete with medicine, to be believed, to believe one’s own body, and to persist outside the forms of productivity that justify our lives?

In chronic illness and disability, affected people don’t go away – ‘neither dead nor recovered’, as Alice James described herself. They terrorise and are terrorised by the Protestant ethic. Spoon theory – a metaphor proposed by the American blogger and lupus patient advocate Christine Miserandino, and embraced by physicians – suggests that people envision their energetic resources as a collection of spoons that are used up throughout the day. Sick people, on some days, will begin with fewer spoons and need to exercise more careful thrift. ‘Spoonies’ identify their disability with the currency that measures it. The metaphor of responsible spending, though helpful in daily life, skirts the question of what happens when you don’t have enough spoons to pay for astronomically marked-up medicine, student loan interest or rent.

At this occluded margin, people are forced to leave work or declare bankruptcy to qualify for means-tested public benefits. Here, society’s blithe assurance that spoons, work ethic, financial planning or health insurance mean anything is thrown to the wind. The Taiwanese-American writer Esmé Weijun Wang in 2016 recounted having her disability benefits cancelled when she was too sick to fight for them. Though insurance companies and social services scrutinised Wang’s every move, even hiring a private investigator, they sought grounds for denial and negation, a sight that unsees.

The rest cure didn’t change my desire to work as a matter of both spiritual necessity and survival

American culture hates to look at this haunted attic of capitalism. Everything that touches it is devalued: home health aides – the country’s fastest-growing workforce as Baby Boomers age – make only $8 an hour in some markets. Sometimes a mystery requires us to look outward rather than inward. How can any of us consider ourselves well or free, when certain punishment for having a body hangs over our heads?

Being forced to take the rest cure didn’t change my desire to work as a matter of both spiritual necessity and survival. Perhaps I was beholden to the widely cherished myth that not just working hard, but loving work, would keep me safe. I knew better, but we carry these myths around despite evidence to the contrary. And this enjoyment of work is more than a protective hex against a precarious, flexibilised labour market. I like work because we make all kinds of beautiful things in order to live, as an expression of living. Human capital never rests, and I’ve become wary of the anxious restlessness in myself; I no longer see it as part of who I am, but as something that has colonised our interiors and extracts more profits the less we are at peace.

I haven’t yet summoned the strength to peer into the online spaces of today’s coronavirus ‘long haulers’ who, as we approach six months of a world transformed by pandemic disease, will qualify as chronically ill. There is a chaotic relish to the disregard with which the US government sacrifices millions of lives to capital. When the sickroom becomes a workplace, and the workplace a sickroom, the penetration of tracking and monitoring becomes limitless.

As the lie of virtuous self-improvement falls away and the noose of punitive feedback loops tightens, reversing course is not just a matter of privacy protection or paid sick leave. It means decommodifying human bodies, health and capabilities through universal healthcare. It demands a new kind of economy in which our work is generative for society, organised around our needs, and dedicated to our survival rather than to escape pods for the ultra-rich.

We can close the curtain on this morality play in which we strive to justify our existence while monitoring others for signs that they don’t measure up. The majority of Americans who labour under precarious circumstances see that ‘productive value’ means nothing to us; it’s not far to concluding that we are an indestructible quantity.