Upon its publication in 1922, critics agreed that James Joyce’s Ulysses was the masterpiece of the age. No work of literature more fully embodied the experiments in literary form essential to modernism. But even its most ardent advocates had to admit to its many Rabelaisian moments. Joyce revelled in what Edmund Wilson in 1929 described as ‘this gross body – the body of humanity.’ As the literary historian Paul Vanderham asserts, the obscenity in Joyce’s work ‘is something more than a Victorian fantasy.’ He transgressed literary and moral categories, and his book was indeed profane, scatological and salacious.

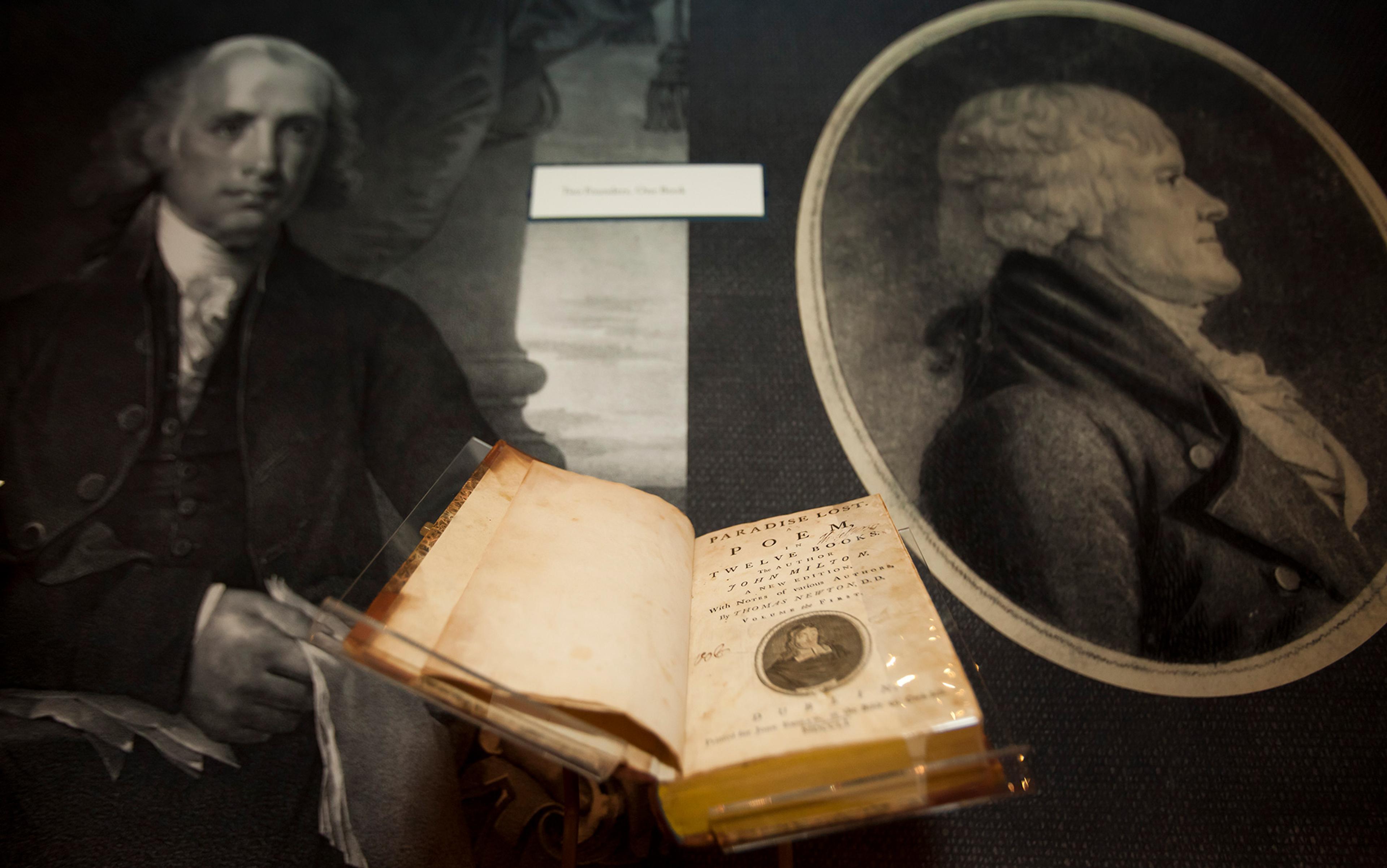

All of which meant it fell afoul of obscenity laws in the United States. Widely known as the Comstock Laws, this legislation strictly prohibited materials seen as lewd, indecent, lascivious, and immoral, to list some of the synonyms used to define obscenity in the federal statutes. Joyce’s novel was rife with such matters, and Ulysses had been ruled obscene in the US from its initial instalments published in The Little Review magazine during the First World War. A 1928 US Customs Court decision ruled the entire book obscene.

The fact that Ulysses was still banned in the US a full decade after its publication struck denizens of the literary world as absurd. Malcolm Cowley, editor of The New Republic, captured the exasperation when he wrote that ‘James Joyce’s position in literature is almost as important as that of Einstein in science. Preventing American authors from reading him is about as stupid as it would be to place an embargo on the theory of relativity.’ But freeing Joyce’s masterwork from the clutches of the censors would require prodigious effort, legal aplomb, and federal judges willing to hear the book’s defenders.

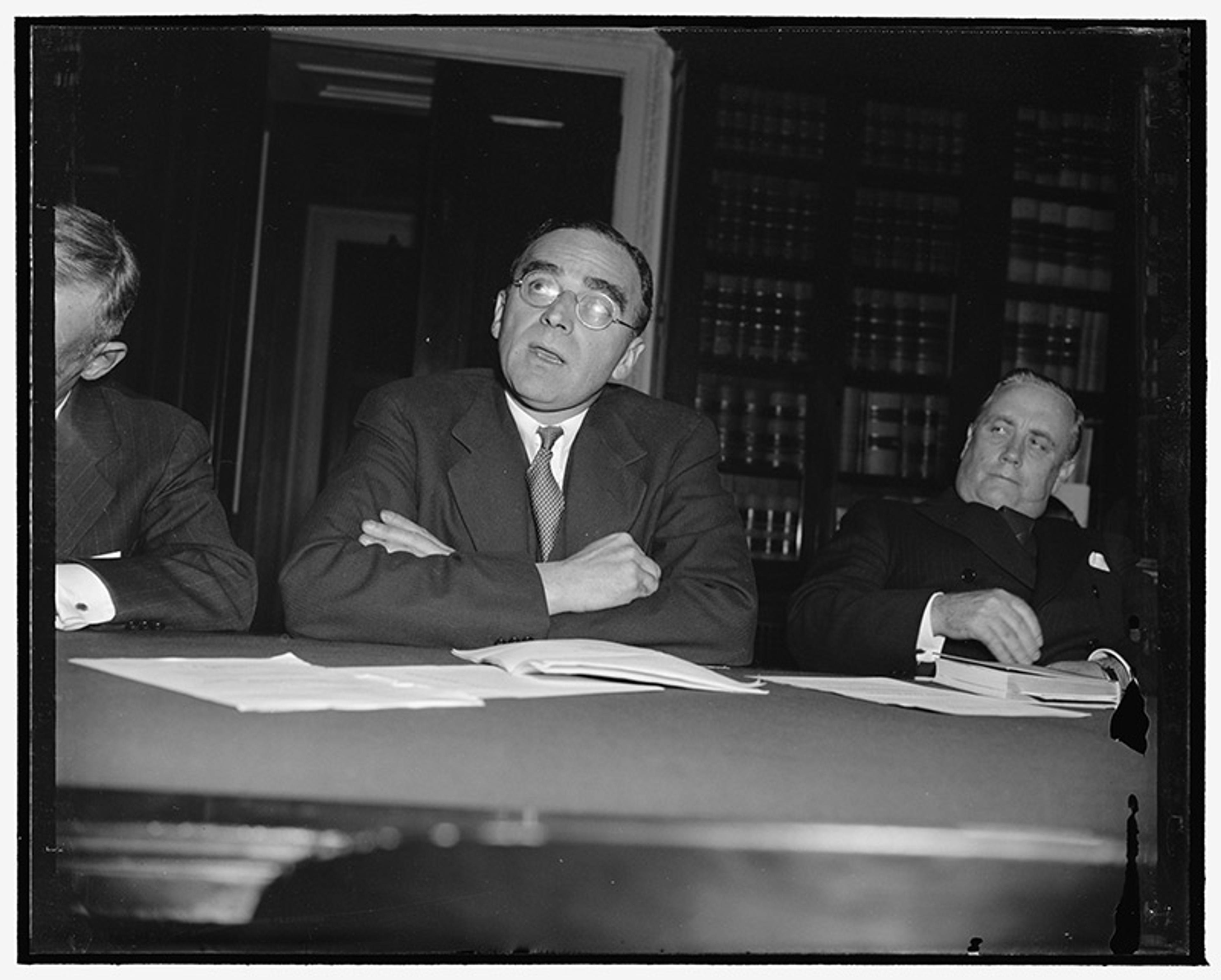

Morris Ernst arguing for the Ludlow resolution to place the power of declaring aggressive war in the hands of voters, May 1939, New York. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Two New York lawyers, Morris Leopold Ernst and his junior partner Alexander Lindey, had the requisite aplomb, as revealed in a note Lindey wrote to Ernst in August 1931 about taking up the defence of Ulysses: ‘I still feel very keenly that this would be the grandest obscenity case in the history of law and literature, and I am ready to do anything in the world to get it started.’ Lindey was right about its grandness. And their optimism about the outcome wasn’t naive either. The two had already obtained legal precedents in a series of earlier cases in which they successfully challenged the application and administration of federal obscenity laws against other notable artefacts deemed obscene. They had laid the groundwork for defending Ulysses, and had learned how to breach the nation’s obscenity laws.

The federal and state obscenity laws Ernst and Lindey targeted before taking Ulysses to trial sanctioned not just the suppression of literary works, but forbade the distribution of sex-education materials, marital advice manuals and virtually anything having to do with contraception, including birth-control techniques and devices. The Comstock Act of 1873 was the most formidable of these laws. Formally known as the ‘Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use’, the statute was capacious in its breadth, giving US Postal and Customs officials a wide berth to patrol the mails and ports of entry for allegedly obscene goods.

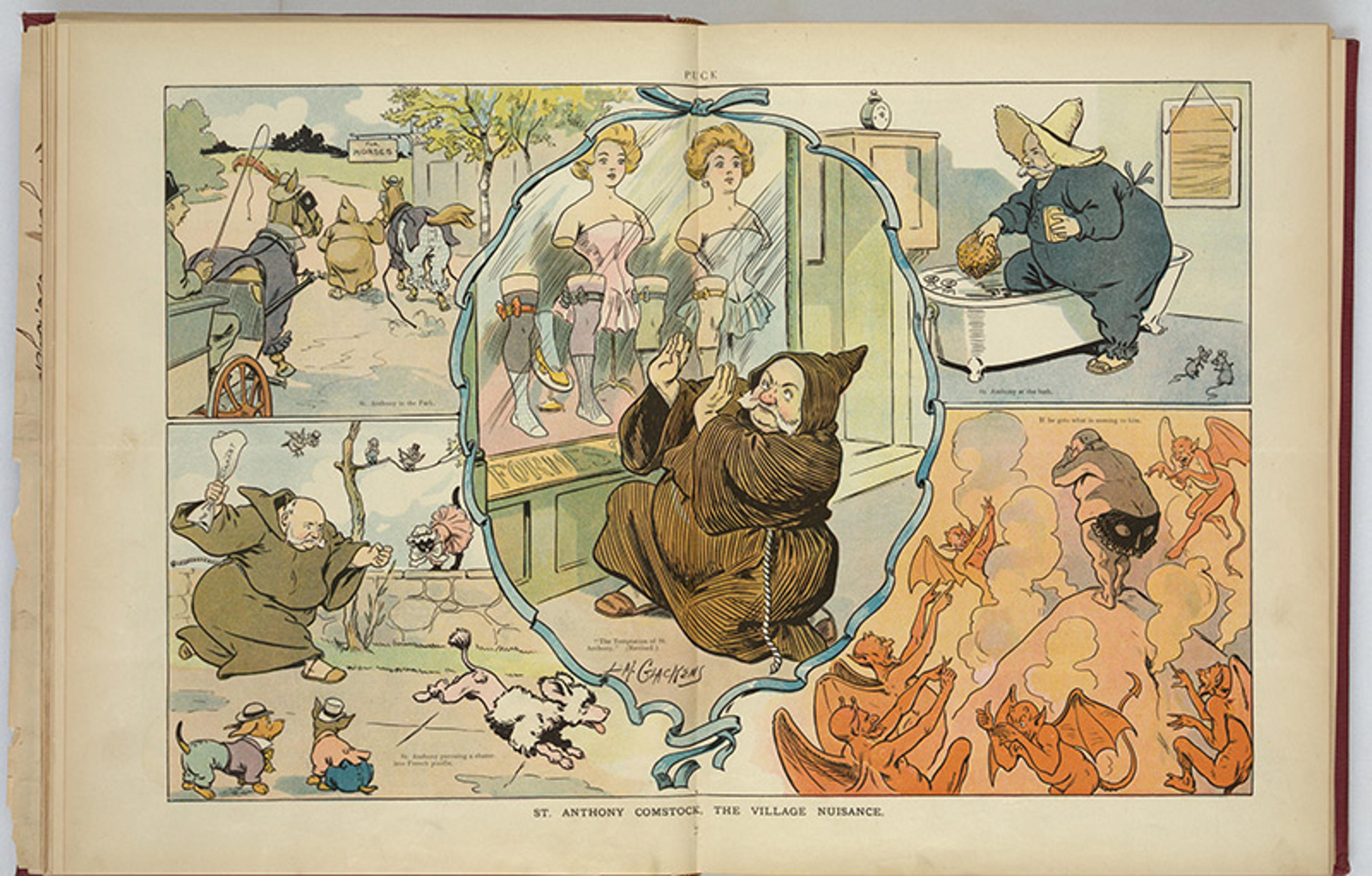

St Anthony Comstock, the Village Nuisance (1906) by Louis M Glackens. Courtesy the Library of Congress

The Comstock Act also gave the law’s author, Anthony Comstock, enormous authority. Already the executive secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (a private organisation financed by the city’s elite), the federal law enabled him to search the mails, secure arrests and convictions, and destroy material seized from the mails. He had special police powers in New York City as an agent of the New York Police Department, allowing him to conduct raids on bookstores, publishers’ warehouses, theatres and other sites of ‘vice’, including houses of prostitution, gambling dens, saloons and dance halls.

Anti-vice organisations incurred virtually no opposition from politicians

A devout evangelical Christian, Comstock presented himself as an avenging hero against forces of moral disruption and sinfulness, referring to himself as a ‘Soldier of the Cross’. Highly controversial and oft satirised, Comstock maintained the support of many of the era’s elites who agreed that strictly enforced obscenity laws were necessary tools for keeping sex, sin and disorder at bay. He was a brilliant publicist who warned against the power of a sexualised popular culture to undermine the moral sensibilities and self-discipline upon which the social order supposedly depended.

Comstock, of course, was not alone. There were anti-vice organisations throughout the nation’s largest cities and smaller towns. They enlisted clergy from all denominations, found eager activists in women’s civic groups, drew upon the financial resources of leading male citizens, and could count upon police enforcing the laws while judges upheld them in the courts. They incurred virtually no opposition from politicians.

In the law, Comstockery lasted well beyond his death in 1915, partly because the courts continued to uphold the law’s constitutionality and allowed their administration to go unchecked. Crucially, his cultural work was carried on by his successor as Vice Society head, John Saxton Sumner – and it is he who became Ernst’s primary target in the struggle over obscenity laws.

Ernst was a hustler. He was peripatetic. He was ambitious to be known, and he liked to be thought of as connected to those in power. Born in 1888 in Alabama, he was the son of a Jewish immigrant from Pilsen, Germany on his father’s side, and a second-generation Jewish immigrant on his mother’s. His mother took ill when he was a child, and he lived with an uncle and aunt, separated from his siblings. In an interview late in life, he reflected that he had ‘no ancestors’ and ‘no past’. Asked to explain, he said he had ‘no great grandfather, no rootedness’ and no sense of security. His second wife, Margaret Samuels, who came from a well-established Jewish family in New Orleans, ‘had security, I had none.’ He continued: ‘I’m a ham. I like publicity.’

His second-generation immigrant sensibility and his attendant insecurity come across potently in this interview. He did not discuss his Jewishness per se, other than calling himself a ‘non-worshipping Jew’. Perhaps he did not discuss his Jewish identity much because it made him feel vulnerable. His biographer Joel Silverman writes that Ernst ‘recalled how he was mocked during his formative years for his appearance. “I had been brought up to believe that I was ugly … I had uncles who always kidded me about my big Jewish nose which did my ego no good.”’ He also remembered being ‘told that I was Jewish, and for that reason, inferior.’

Ernst internalised the financial precariousness of immigrants, too. His father, Carl Ernst, made (and occasionally lost) money in the real estate business, so his family endured difficult periods. Still, Carl had enough financial success that he could send Morris to the prestigious Horace Mann School in New York for Ivy League prep, and then to Williams College in Massachusetts. At Williams, Ernst was one of the few Jewish students, and was aware of how his Jewishness (and small physical stature) marked him. But he was gregarious, a successful debater, and fit in well enough to be accepted into a Jewish fraternity. Upon graduation, he lived in New York City, working in the family shirt-making business (established by his father and uncle), and took up night classes at the New York Law School where other immigrants and Jews took their legal education. Ernst later formed his law firm – Greenbaum, Wolff, and Ernst (GWE) – with Jewish students he met at Williams College.

Always self-deprecating about his legal education, Ernst often remarked that he was a ‘partially trained’ lawyer and called himself a ‘dilettante’. This sense of being dilettantish was no doubt connected to his sense of the inadequacy of his legal training. While he may have described himself as a half-trained lawyer, other civil libertarians of his generation recognised his talents and his energies. He quickly rose in the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to become an executive member and co-general counsel to the national board from 1929 to 1955. The ACLU’s post-First World War commitment to expanding civil liberties across multiple fronts reinforced his free-speech ideals.

Ernst waged his anti-censorship campaign in the courts, as well as in the court of public opinion

Ernst began laying the intellectual groundwork for a strategic attack on the obscenity laws when he undertook a lively historical study of Anglo-American censorship practices titled To the Pure (1928). His steady, piecemeal campaign against the obscenity laws was significantly aided by Alexander Lindey, who joined GWE in 1925, upon graduating from the New York Law School. Lindey was one of a handful of junior associates in this highly successful Jewish law firm who worked alongside Ernst on his censorship cases, and helped make GWE the key player in fighting for sexual liberalism in the US courts prior to the Second World War.

While the ACLU was deeply involved in promoting what the historian Leigh Ann Wheeler describes as ‘sex as a civil liberty’, Ernst was the architect of decisive trials from the late-1920s to the beginning of the war, and his firm did much of the work pro bono. Pursuing what Ernst described as ‘rational sex laws’, GWE took on obscenity laws as well as the wider culture of Comstockery, which they saw as responsible for irrational sex laws, over-zealous application of vague 19th-century statutes, and the unseemly deference accorded to administrative censorship authorities. They did their work on behalf of the many publishers, writers, birth-control activists, sex educators, bookstore owners, burlesque theatre owners and others who ran afoul of those laws.

Ernst waged his anti-censorship campaign in the courts, as well as in the court of public opinion, constantly vilifying and brawling in the city’s newspapers and magazines with John Saxton Sumner of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Ernst spent years building momentum for the anti-censorship cause and garnering allies among those victimised by Sumner. Ernst was more pragmatic in the actual courts, where he defended credible materials whose status as ‘obscene’ was contestable; he and Lindey carefully built their cases and wrote impeccable, erudite legal briefs aimed at persuading judges that the Customs and Postal authorities were seizing works with demonstrable value to the public.

New York City was a stage for Ernst, an ideal place for him to wage his battles, not least because Sumner was a great foil who could be held up to the public as the antithesis of the city’s cosmopolitanism. Moreover, New York was the centre of the US book publishing world, and Sumner had so much clout over what publishers could risk publishing that he antagonised the intellectual class. He monitored publishers’ lists, warned them he would go after them if they published works he thought were obscene – such as Ulysses itself – and often followed through on his threats by raiding publishers’ offices, bookstores and magazine stands, all with police and photographers in tow. Ernst easily painted him as an anti-democratic scourge, the censor who was utterly out of touch with the spirit of New York City. Ernst and Sumner shared a deep animus, which fed journalists’ accounts of their skirmishes.

Ernst and Lindey won acclaim in a series of high-profile cases leading to the defence of Ulysses. They successfully defended the birth-control pioneer and sex-education pamphlet-writer Mary Ware Dennett (in the case of US v Dennett), the British birth-control advocate and sex educator Marie Stopes (in the cases of US v One Obscene Book Entitled Married Love and US v One Book Entitled Contraception), the novelist Radclyffe Hall, and Margaret Sanger’s birth-control clinic following a police raid in 1929. Their fight against Comstockery gained momentum, as did their sexual liberalism, which emphasised freedom of expression at the expense of oppressive, capricious moralism. They readied themselves for their crowning victory.

One can usefully interpret Ernst’s challenges to the obscenity statutes and their administration as being essentially a parallel free-speech movement to the one his ACLU colleagues took up on behalf of political radicals and labour unions in the 1920s and ’30s. Free speech was in the air in civil liberties circles, and Ernst and Lindey succeeded in part because they effectively mobilised an already available free-speech tradition. They gave voice to a body of arguments familiar to Americans across social classes, not just against censorship but on behalf of deeply held ideas about free speech and political liberty. Those ideas gained adherents in the face of rising totalitarian threats in the 1930s and beyond. Even if the First Amendment did not protect all forms of speech and expression, literary censorship in particular came to be understood as anti-modern, anti-intellectual and anti-democratic – and this aided the anti-censorship cause. Nazi Germany revealed what an odious practice book burning was, and how much it contravened democratic ideals of free speech.

Ernst also effectively rooted his arguments about the value of his clients’ work in terms of modern democratic theory: the rational, self-determining adult was capable, and therefore ought to have access to a diverse marketplace of ideas. Adult interests and needs mattered in this marketplace. Moreover, the censors’ and prosecutors’ assertions of moral harm to unknown readers were simply inadequate as evidence of actual harms, and demonstrating actual harm was crucial as a due process matter in criminal law. The law’s assumptions about potential harm to some unknown reader had to be weighed against the potential – and actual – medical value of contraceptives, or marital value of sex education, or intellectual value of modern fiction.

The greater harm to democratic life lay in the state’s vaguely written laws, administered by anonymous figures

His experts assured judges that there was manifest public value in adult citizens having access to up-to-date, scientifically credible information about the mysteries of human sexuality, in reading about complicated matters of sexual desire, in controlling their reproductive lives, in achieving greater marital happiness, in reforming laws that penalised people for sexual acts that were actually widely practised. The laws lagged far behind people’s actual behaviour. Ernst was a small-d democrat who invoked the competent, rational adult citizen at the conceptual centre of democratic theory. Democracy demanded that rational adults be able to navigate a thriving marketplace of ideas.

Ernst’s fight for Ulysses against the obscenity laws was fired by his conviction that the greater harm to democratic life lay not in some readers possibly being aroused by reading modern fiction, but rather in the state’s continued use of vaguely written laws, administered by anonymous figures in impenetrable federal agencies, whose decisions were rarely challengeable. While reading certain kinds of materials might well inspire lust, the true harm was in depriving citizens of access to the great works of modern literature.

When Ernst and Lindey finally freed Ulysses in 1933 (a decision upheld in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in 1934), the win brought Ernst near-celebrity status in the New York City literary world, as well as in the nation’s civil liberties circles. For a time, he was recognised as one of the most important civil libertarians in the US. In 1944, Life magazine, one of the 20th century’s most widely circulated periodicals, published a multi-page profile of Ernst, introducing the broader public to his accomplishments in the realm of sexual and literary free speech. The focus was Ernst’s remarkable string of victories in high-profile sexual censorship cases. Life’s Fred Rodell ascribed Ernst’s success to his abundant energy, alert eyes and athletic strength, and to his ‘exhibitionism’ – that is, his desire for fame.

The Ulysses case earned Ernst the reputation of being preeminent ‘among lawyers crusading against censorship’. As an earlier essay in Scribner’s noted: ‘Before Ernst came along, the vice crusaders used to scare booksellers into pleas of guilty and light fines by promising to get the case over quickly, and without publicity.’ But by waging ‘almost continuous warfare against Federal, State, local, private, and ecclesiastical censorship bodies’, Ernst changed that dynamic. As the Life profile observed – with a dig thrown in – Ernst could ‘crow, with pardonable pride’ that ‘no book published by a regular publisher or reviewed by a regular critic, no book published honestly and without surreptition, is in any danger of suppression.’ In 2019, the novelist Michael Chabon, in The New York Review of Books, hailed Ernst’s defence of Ulysses. Ernst was ‘known, and much sought-after, as a gifted, skilled, and cagey courtroom attorney with a discerning eye for the kinds of cases that could change the law if you won them.’ Chabon proclaimed that Ernst achieved a level of mastery similar to Joyce’s, as he had ‘brought as much artistry and erudition and sly, masterful skill to defending one book, called Ulysses, as its author had brought to its creation.’

But Ernst’s story did not end with Ulysses. His own growing concern with the threats to US democracy in the late 1930s led him down a path of increasing intolerance toward US communists. Deep rifts formed between himself and other ACLU leaders, and his record became especially troubling when he took up a friendly, even sycophantic, relationship with J Edgar Hoover, whose five-decade reign at the helm of the FBI was fraught with illegal, unethical, anti-democratic activities that destroyed many careers and took some lives. In the decades after the Second World War, Ernst lost track of his core free-speech principles. He framed nearly every issue through the Cold War lens of the struggle between democracy and dictatorship. He came to argue repeatedly that US communists did not have free-speech rights because of the dangers they posed to US democracy.

Ernst and his colleagues helped make anti-censorship principles core precepts of modern US liberalism

In the furores of that tempestuous era, Ernst discarded his civil libertarian bearings. Nearly all his allies from earlier battles deserted him. His former friends and admirers asked how Ernst – the great ACLU leader and defender of Dennett, Stopes, Sanger, Joyce, Alfred Kinsey, and many other sexual modernists – could make common cause with Hoover? Perhaps it was in the vain hope that he could make Hoover more solicitous of due process. But, if so, he was duped. Their entirely one-sided relationship destroyed Ernst’s reputation with civil libertarians, and Ernst’s legacy has taken a beating from which it is not likely to recover. I’m not aiming to recuperate his reputation.

However, I think it is important to separate Ernst the flawed man from Ernst the anti-censorship strategist who took on the formidable censorial power of the federal and state obscenity laws. Ernst and his colleagues gave legal counsel to some of the great protagonists of the first sexual revolution and helped make anti-censorship principles core precepts of modern US liberalism, shaping the law to better protect personal sexual privacy, sexual selfhood, reproductive autonomy, sexual self-determination, and the right to not be discriminated against on the basis of sex and sexual identity.

In the past several years, the US has witnessed a rash of censorship laws and book bans, a political backlash designed to turn back the clock with regard to human sexual freedom, knowledge about race and racism, and women’s reproductive rights. Not surprisingly, conservatives are invoking the availability of the 19th-century ‘Comstock’ obscenity laws – never fully repealed – to prohibit the interstate distribution of the drug mifepristone (part of the so-called ‘abortion pill’). They are also appealing to Comstock himself as a beacon in their efforts to combat abortifacients and contraceptives, sex education, positive portrayals of the LGBTQ+ community, and anything else they perceive as ‘obscene’ or ‘pornographic’.

That the 150-year-old federal statute authored by Comstock is being invoked in 2023 is chilling, and it reveals just how reactionary and puritanical the US Right has become. Attacks on sexual identity, sexual knowledge and female reproductive autonomy have been the main issue of most of the ‘culture wars’ disputes over the past four or five decades, especially the assumption that women’s bodies are the subjects of men’s political and personal access. These notions are at the heart of patriarchal thinking – as they were in the age of Comstock. And now, the cruel contemporary conservative assault on trans people – their right to public presence, their right to medical knowledge and technologies, their right even to straightforward medical advice – is gaining momentum.

Ernst and his colleagues clearly understood that the public should have access to a dependable, well-sourced, up-to-date marketplace of sexual knowledge that might make people’s lives happier and more fulfilling. Personal autonomy and access to knowledge, they reckoned, is the starting point for achieving personhood in a democratic society. They would certainly recognise that their legal work is far from done, and would be horrified that the ghost of Comstock is being welcomed back by Right-wing legal architects opposed to abortion and contraceptive access generally. US progressive forces – lawyers and journalists, in particular – would do well to recall the work of the long-forgotten Morris Ernst.