The 16th-century Tempietto designed by Donato Bramante in Rome stands at the heart of Western architectural history. Its iconic bull’s eye plan, with concentric circles radiating outward from a single point, coincides perfectly with the central status assumed within the architectural canon by this ‘little temple’. Architectural historians often argue that the Tempietto functions as a compelling geometrical metaphor for Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ (1490) – his study of the body’s proportions – where both of these designs exalt the human form by placing it firmly at the centre of a perfectly ordered universe.

And yet the comparison of these two images encourages us to think of the Tempietto in terms of a disembodied pattern of visual forms, rather than a physical environment built to accommodate dynamic, living human bodies. As the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa has shown in his classic manifesto The Eyes of the Skin (1996), architecture offers an immersive, embodied experience that engages not just the eye but all of our senses simultaneously. Our overwhelming emphasis upon the visual aspects of architectural design fails to acknowledge the fact that, to gain understanding and knowledge of buildings, we rely upon all of our senses, including sight, sound, smell, taste and touch, as well as bodily senses such as proprioception and kinaesthesia, which are associated with balance and movement.

Here I want to reconsider the Tempietto by shifting our attention away from the hypnotising perspective of the eye, to investigate how a complex variety of sensory experiences defined the encounter with the Tempietto for 16th-century visitors.

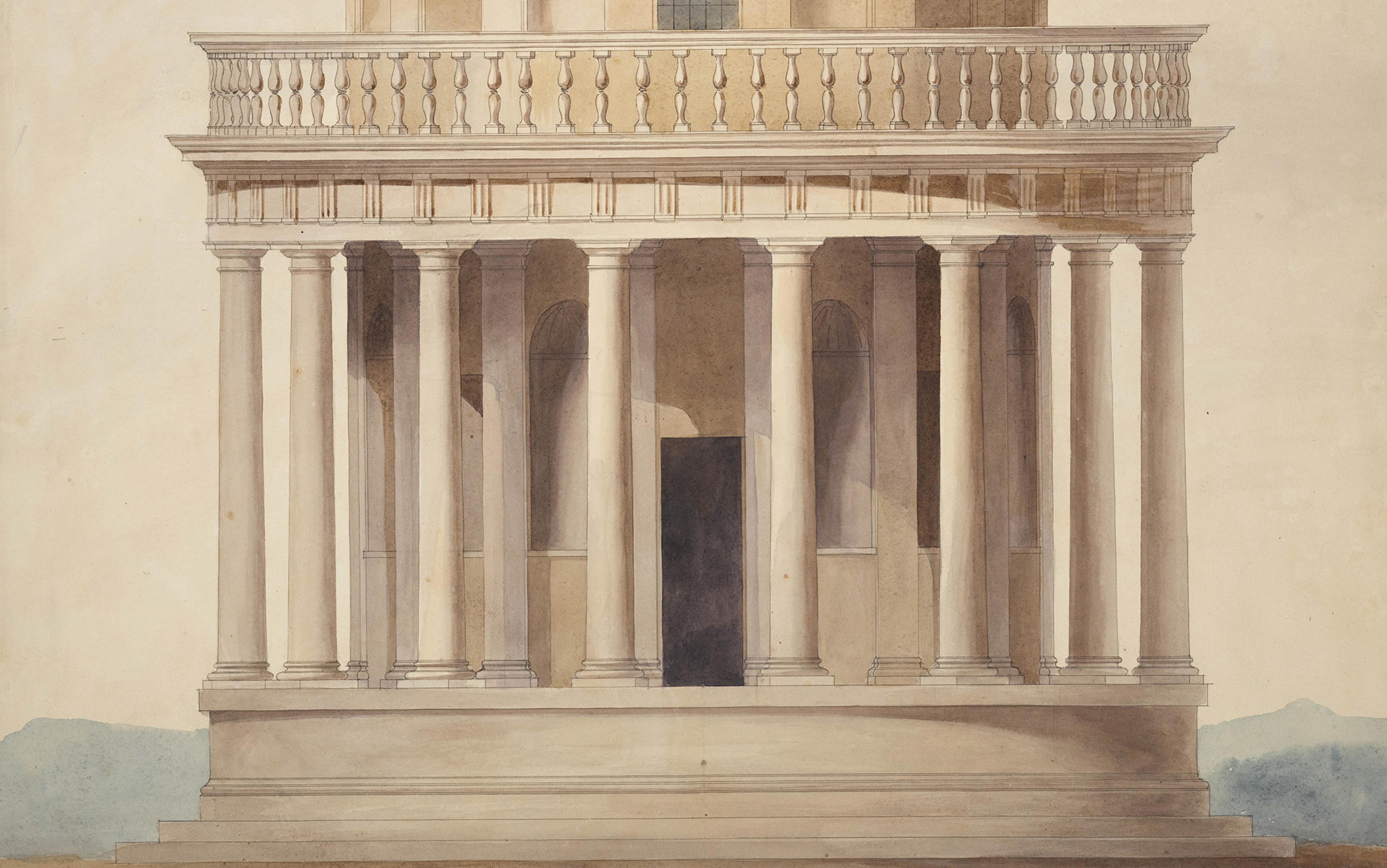

The Tempietto has enjoyed a remarkable afterlife. In his treatise I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570), Andrea Palladio included the Tempietto – completed in 1502 – among the greatest monuments of ancient Rome, justifying this choice with the affirmation that its designer, Bramante, ‘was the first to bring to light the good and beautiful architecture that since the time of the ancients until the present had been hidden.’ For Palladio, the Tempietto matched the greatest works of antiquity, signalling a victorious return to the ‘good and beautiful’ classical language of architecture forgotten by medieval builders.

Although the Tempietto stands discreetly hidden in the courtyard of the church of San Pietro in Montorio, Bramante put it on the world stage by choosing it as the model for his redesign of St Peter’s Basilica, begun in 1506. The massive cupola of St Peter’s – completed a century later – is a scaled-up Tempietto that still dominates the city of Rome today, a triumphalist symbol of the universal aspirations of the papacy and the Church. Raised high above the urban landscape, its spectacular tiered profile has inspired the design of numerous religious and secular monuments around the world, from St Paul’s Cathedral in London to the US Capitol in Washington, DC.

And yet even if we instantly recognise the Tempietto’s silhouette, this visual familiarity is not equivalent to the complex experience of occupying and moving through such a structure with our bodies. A building can shape an endless variety of experiences – not only stimulating the sense of sight, but how and what we hear, smell, taste and touch. When we consider sensory experience as a historically and culturally situated phenomenon, the question becomes even more complex: is it possible to recuperate something of the impressions that this building made upon those who encountered it at the time when it was built?

The Tempietto is closely associated with the development of linear perspective

Even if we assume that, today, we have roughly the same human physiology as those who lived in 16th-century Rome, each of us interprets our experiences through lenses shaped by the time and place in which we live. The Tempietto can be read as a complex physical object designed to stimulate the senses in many different ways, creating a whole host of experiences that may or may not align with our own expectations. By beginning to reconstruct other ways of knowing this architecture, we can begin to recognise how even a visual icon like the Tempietto offers more than just a feast for the eyes, and instead is capable of creating an infinite variety of lived interactions.

Why do we automatically privilege the sense of sight when we think of the Tempietto? One reason is that the Tempietto is closely associated with the development of linear perspective, and axially constructed views of the structure showing it in strict single-point perspective reinforce the impression that perspectival concerns played a dominant role in its design. The Latin word perspectiva derives from perspicere, meaning ‘to see with clarity, to examine, to see through’, and was in fact a synonym for optics. Architectural historians tend to view the transparent lucidity of the Tempietto’s design – revealed not only in the elegance of its centralised plan but even in its precise architectural detailing – as a hallmark of Renaissance architecture.

Given the overwhelmingly visual characteristics that architectural historians associate with the Tempietto, it is hardly surprising that visual readings of the structure prevail over all others: the history of Renaissance architecture itself encourages us to approach the building in this way. But our insistent visual emphasis also makes it more difficult for us to recognise how we might potentially interact with the Tempietto in other ways.

Was Bramante’s Tempietto really meant to be appreciated only with the eyes? Historic sources can help us to recuperate other, more complex understandings of these structures and spaces that our fixation with sight may have led us to overlook. To begin, let us consider an excerpt from Vincenzo Scamozzi’s architectural treatise, L’idea dell’architettura universale (1615). Scamozzi provides an astonishingly visceral account of the importance of multisensory knowledge for the people who worked on building sites for structures such as the Tempietto. This discussion invites us to consider how builders employed many different ways of discriminating between various kinds of materials – even to the point of sampling them with their tongues – as opposed to the more detached, not to say disembodied, interactions that we have with building materials today:

Stones are known through the senses: when they are tougher and harder this can be easily detected by the eye: they have lustre, and sometimes the glint of salt crystals; to the ear they make a full and sonorous sound, especially in the larger blocks; in terms of smell they produce an odour of sulphur … above all when they are struck with toothed hammers, or when they are scraped with an iron blade; in terms of taste some have less quality and flavour than others, such as those that are composed more of water than of earth; and finally, in terms of touch some are denser and heavier than others. Also through our breath we recognise those stones that are harder and denser than the others, as the denser stones immediately reveal the breath’s humidity on their surfaces, especially when they are buffed and polished, but the softer stones absorb the breath into themselves due to their porous nature.

If architectural historians are inclined to privilege the experience of sight in their study of Renaissance buildings, Scamozzi tells us something completely different. On the contrary, he is keenly aware of the ways that building materials engage many different sensory modes. In his book The Five Senses (2016), the philosopher Michel Serres speculates that all of the senses are ultimately variations on the sense of touch, and I would argue that Scamozzi’s passage is permeated by a tactile presence. It is easy to imagine a stoneworker’s fist tensed around the handle of a chisel just before striking a chunk of stone, or the way that one’s breath briefly warms a cold geological matrix, or even how one might detect a curious mineral flavour by touching one’s tongue to a stone surface.

It is easy to imagine him passing his palm appreciatively over the rounded surfaces of its granite columns

Scamozzi invites us to bring the elements of architecture close to us and to investigate them from all angles in order to understand them better, and thus to manipulate them better. Far from a fixed, motionless object perceived through the eyes, Scamozzi insists that builders in the Renaissance knew their building materials, and by extension their buildings, by employing all of their senses, where they acquired this specialised sensory knowledge through ongoing lived experiences on the worksite. This knowledge enabled these builders not only to judge the specific qualities of individual materials, but to imagine various scenarios where these qualities also could be leveraged to their greatest potential. While Scamozzi focused in particular upon stone as the most privileged material of Renaissance architecture, surely Renaissance builders might also judge other materials – timber, iron, glass, brick, plaster – based upon a wide-ranging variety of sensory knowledge. According to Scamozzi, mastery of the trade required internalising these specific material properties and characteristics, where these accumulated sensory experiences could become an instinctual way of responding to and thinking about the world.

What does this mean in terms of the ways that the sensory experience of a visitor to the Tempietto in the 16th century might differ from our own? Scamozzi’s text revealed the builders’ specialised material knowledge gained through first-hand exposure to an active construction site, as well as the sensory skills they could then bring to bear upon the building. While few of us today could claim such knowledge or skills, we can see how their experience carefully honed the Renaissance builders’ sensorium to distinguish precise material qualities.

When we consider Palladio’s specialised training as a mason-turned-architect, we recognise that his earnest praise for Bramante’s recovery of the ancient way of building carries special weight. Palladio undoubtedly visited the Tempietto, and although he may not have gone so far as to taste the Tempietto’s surfaces, it is easy to imagine him touching the sharp profile of a column base with his fingers or passing his palm appreciatively over the rounded surfaces of its granite columns. The complex variety of experiences that a building creates for us can affect us in many ways, physically and intellectually, as well as both consciously and unconsciously.

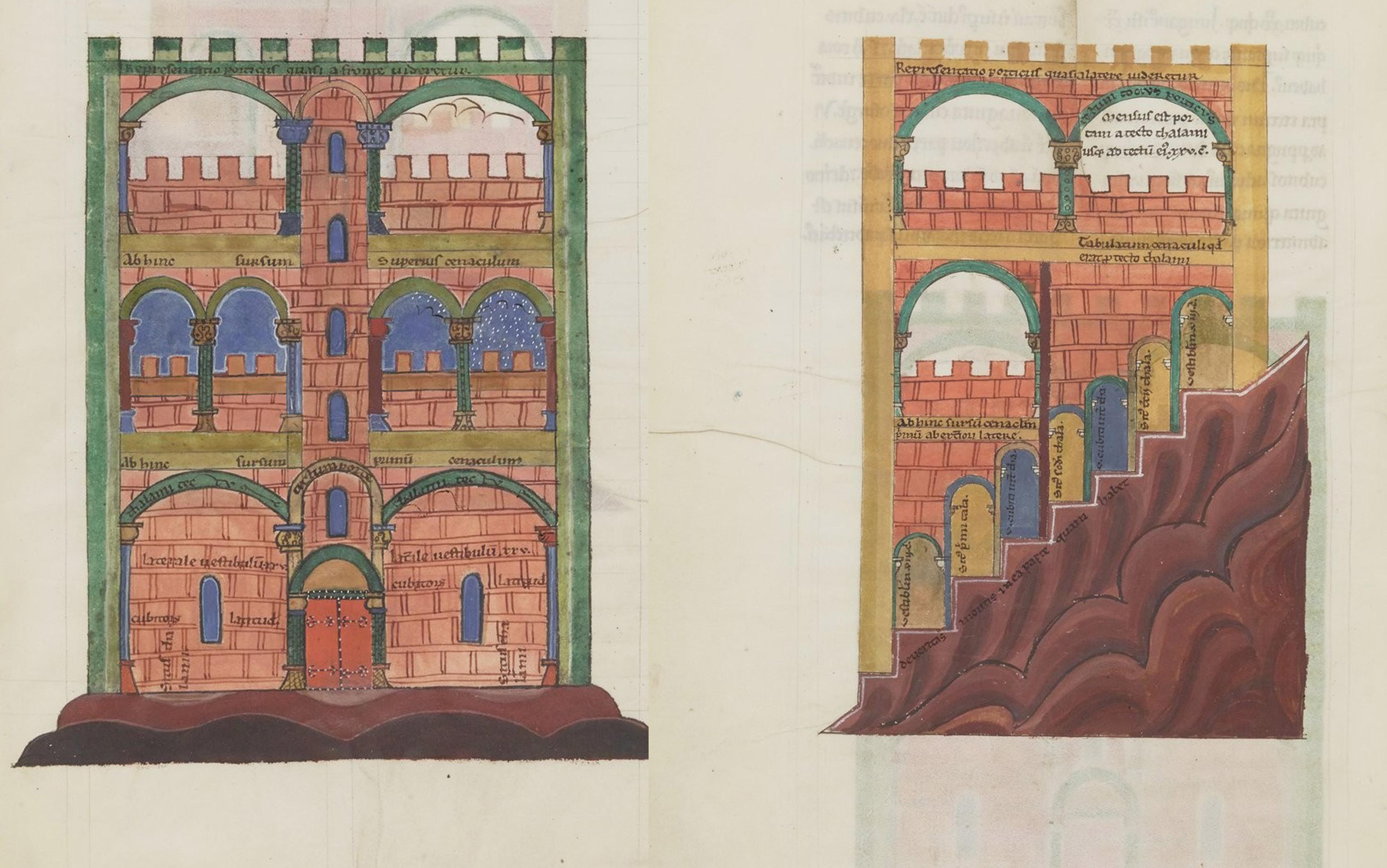

The centralised plan of the Tempietto commemorates the exact location where the crucifixion of St Peter – depicted in a painting from 1601 by Caravaggio that’s also in Rome, at the Santa Maria del Popolo – was believed to have occurred. The rigorous geometric clarity and coherence of the Tempietto’s design corresponded to the design of an early Christian martyrium, a structure built to mark the burial place of a saint. The building consists of two chapels, an upper chapel under the dome, set above the crypt chapel below, containing the holy site. As architectural historians often note, the concentric circles of Bramante’s plan draw our attention inexorably toward the single point at its absolute centre.

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

The Crucifixion of St Peter by Caravaggio (1601). Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. Image courtesy Wikimedia

By considering the Tempietto’s function as a pilgrimage destination, we may begin to recover some of the sensory experiences that the site offered its visitors in the Renaissance. Despite the prominent place of the Tempietto in the history of Renaissance architecture, the building itself did not represent the ultimate destination of those pilgrims who came to visit the site of St Peter’s crucifixion. Rather, their primary goal was the ground that lay below the structure, where St Peter’s persecutors drove their crucifix into the earth.

Subsequent alterations to the Tempietto have made it harder for us to discern the way that pilgrims originally encountered the site. Today, we can peer through a grille placed in a circular opening in the floor of the upper chapel in the Tempietto, which in turn allows us to see down to the floor of the crypt chapel underneath, where a circular opening to the earth below marks the exact point where the crucifix met the ground. Yet the opening that we look through from the upper chapel was introduced only in 1628, during renovations. Prior to these 17th-century interventions, visitors could not see this central point of the Tempietto’s design – the reason for its existence – without physically entering the crypt chapel. In fact, the superstructure of the Tempietto above the crypt chapel obstructed access to pilgrims eager to come into contact with this holy ground.

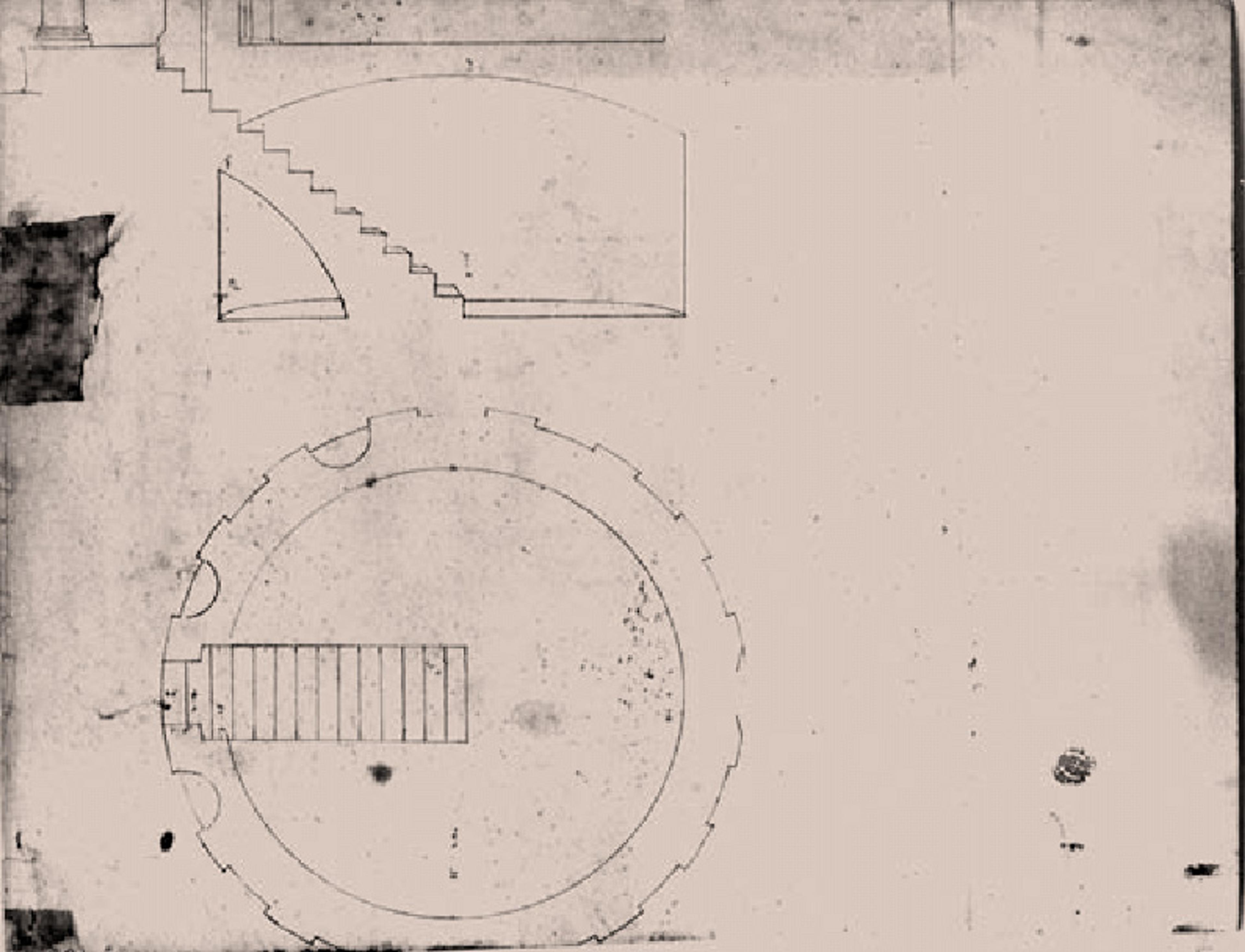

Plan and elevation of the crypt chapel of the Tempietto, Rome. Courtesy Jack Freiberg/Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe

Today, a double-ramp stair at the rear of the Tempietto descends to a sunken landing. From here, another flight of stairs leads down into the crypt chapel. Although metal bars prevent us from entering, the landing offers clear sightlines into the interior space: we can easily see both the circular opening set into the centre of the pavement that marks the location of St Peter’s crucifixion and the altar immediately behind it. However, prior to 1628, the only access to the crypt chapel was via a doorway set into the rear wall of the Tempietto, above the landing, at the level of the colonnade. Placed directly opposite the front entrance to the main chapel, this opening still exists today, although it now functions as a clerestory window into the crypt chapel below. Originally, however, visitors passed through this opening to descend a long, straight flight of stairs leading down to the crypt chapel below.

Pilgrims were spared the dangerous voyage to the Holy Land, and could instead step into a simulacrum

Given the absence of any other windows, the pilgrims required the use of a lantern or a torch, and descended the stairs into the dark. Their descent was made even more treacherous by the absence of railings to hold on to, to maintain balance as they climbed down. At the same time, we know that the crypt chapel also had significant moisture problems: less than a century after the Tempietto’s construction, water infiltration had already caused such extreme erosion that much of the stone revetment covering the walls needed to be replaced. Thus, prior to the restorations of 1628, pilgrims entering the crypt chapel entered a forbidding, dank, slippery abyss. In the effort to improve these conditions, wooden planks were laid down over the crypt floor to absorb some of the moisture. However, the presence of these planks suggests that the pilgrims encountered irregular, if not even precarious, conditions underfoot.

To confront St Peter’s martyrium, the architecture of the Tempietto compelled pilgrims to make a hazardous physical journey that involved multiple, powerful sensory stimuli. We can imagine the shifting, irregular light of the torches on the slow descent; the smell of smoke and fumes produced by the flickering flames; the echoing sounds of voices and bodies reverberating against the wet masonry surfaces; the cautious shifting of weight from one foot to another as the pilgrims moved cautiously downward, unable to rely upon the use of a handrail to steady themselves, feeling their way with their feet; the penetrating odour of dampness and decay seeping into nostrils and mouths; the cold moisture of subterranean air on the submerged skin. In jarring contrast to the longstanding emphasis by architectural historians on the Tempietto as a luminous visual experience, it seems that senses other than sight would have offered Renaissance pilgrims equally if not even more important sources of information during their journey down into the crypt chapel.

Beginning in the 15th century, the Franciscans assumed responsibility for the Tempietto, as part of the monastery of San Pietro in Montorio. The Franciscans’ imaginative efforts to bring the Christian mysteries to life are well known: not only was St Francis credited with inventing the first nativity scene in the 13th century, but beginning in the 15th century the Franciscans created a series of pilgrimage shrines featuring full-scale three-dimensional dioramas such as the elaborate Sacro Monte at Varallo. By visiting these Sacri Monti, or ‘holy mountains’, pilgrims were spared the gruelling and dangerous voyage to the Holy Land, and could instead step into a simulacrum of the sites of the life of Christ. Through the careful creation of these staged scriptural events, the Franciscans sought to impress the biblical narratives on both the minds and the bodies of the pilgrims by transforming the familiar storyline into lived, bodily experiences.

Part of a full-scale diorama at the Sacro Monte at Varallo. Photo courtesy Luiginter/Flickr

Like the Franciscans at the Sacri Monti, the Franciscans in charge of the Tempietto likely also found didactic value in creating such intense sensory experiences for pilgrims visiting the site. The oppressive, even claustrophobic atmosphere of the crypt chapel served to heighten the anguish of the experience, forcing the pilgrims to reflect upon St Peter’s horrific martyrdom. The sense of relief that they would have felt when they finally emerged from the submerged tomb chamber would have been further enhanced by the calm serenity of the Tempietto’s architecture aspiring toward the sky, as a majestic, even joyful anticipation of the ultimate triumph of the Resurrection.

Renovations transformed what had once been an immersive encounter into a primarily visual experience

The subsequent modification of the crypt chapel into an airy, well-ventilated space had profound implications for our sensory experience of the Tempietto’s most sacred centre point. These alterations privilege a more exclusively visual interaction with the site, and reduced the significance of the senses of smell and touch. The new openings improved air circulation, reducing the olfactory encounter with smoke and humidity, and served to direct the gaze of the visitor immediately toward key points of interest.

The original single-ramp staircase impinged upon the centre of the crypt, and thus the reconstruction of the stair outside the crypt chapel opened up an unobstructed view of this holy ground (a grate placed over the opening prevented pilgrims from touching the ground itself). Even the design of the double-ramp stair seems to have been conceived to reduce opportunities for physical contact: pilgrims exited the crypt using a different stair from the one by which they’d entered, thus diminishing the chance of accidentally brushing against each other as they circulated through the narrow space.

Ironically, these alterations occurred as St Ignatius of Loyola and other reformers conjured up the power of the senses to reinforce the spiritual belief of the faithful. In his Spiritual Exercises of the 1520s, Ignatius urged his followers not only to see the length and breadth of Hell, but to hear the wailings of the damned, to taste the bitterness of their tears, to smell the smoke and sulphur, and to touch the burning flames. At the Sacro Monte at Varallo, major renovations by Galeazzo Alessi in the 1560s included the construction of new partition walls and screens to prevent visitors from entering the reproductions of the holy sites, thereby transforming what had once been an immersive encounter into a primarily visual experience.

If the original organisation of the Sacro Monte encouraged pilgrims to participate in the events of scripture with their bodies, the new layout prompted them to use their eyes to imagine such interactions. In the same way, the 1628 improvements to the crypt chapel at the Tempietto enhanced visual access to focus upon spiritual devotion rather than lived experience. Such interventions guided sensory interactions with the world into the narrower spectrum of practices approved by the Counter-Reformation Church, eliminating possible distractions and encouraging more decorous forms of devotion.

At the outset of this essay, I noted that historians have long promoted a specific understanding of the Tempietto in conjunction with Leonardo’s drawing, where the building’s design provides a geometrical metaphor for the exaltation of the human body. But as the art historian Jack Freiberg has shown, the consecration of the Tempietto in 1502 marked the 10th anniversary of the conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, and the first wave of colonisation in the New World, by its patrons Ferdinand and Isabella, the king and queen of Spain. While we have long celebrated the Tempietto as a symbol of the dignity of humanity, the construction of this building coincided with the vigorous expansion of European imperialism and the emergence of modern racist ideologies that we still struggle with today.

We are accustomed to interpreting the Tempietto in terms of humanist ideals, but the placement of a white male body at the centre of the cosmos in Leonardo’s drawing takes on poignant meaning in such a context. If the conventional narrative written by architectural historians about the Tempietto has privileged the sense of sight over the other senses, our emphasis upon humanist ideals has also glossed over the way that this building intersects with the rise of European colonial hegemony. The tectonic shift now underway in response to the Black Lives Matter movement has transformed our understanding of the study and practice of architectural history itself, reminding us of the essential value of other narratives such as these that are all too easily suppressed or forgotten.

What kind of visceral, multisensory reaction might the Tempietto create for the descendants of the enslaved people whose forced labour – enriching Rome via Spain – effectively made this ‘little temple’ possible? The racial reckoning in the study of architectural history converges with the study of architecture and the senses, urging us to consider an expanded range of meanings and experiences that are only now becoming clearer, as part of an architectural history that is still being written.