Listen to this essay

21 minute listen

Across the democratic world, citizens describe a growing sense of powerlessness. Governments rise and fall, but the power to shape daily life now flows elsewhere – through markets, corporations and data systems untouched by democratic oversight. A recent international survey found that, in almost every major country, most people believe the economy is rigged to benefit the rich and powerful; many say their societies are ‘broken’. Discontent has fuelled a turn toward authoritarian politics, which promises control while entrenching new forms of oligarchic rule. One reason the authoritarians are winning may be because liberals and progressives have a deep unease with power.

It’s always the case in history that much about the present moment is unprecedented, and no single perspective is complete, but we don’t have to go very far into history to find a very popular and powerful politics organised around an ideal of freedom that made people fierce opponents of political and economic powerlessness. Economic republicanism was one of the great traditions of 19th-century Western thought, and it appealed to those who felt unable to influence the world around them.

The relationship between freedom and power is at the heart of the republican tradition. For centuries, republican thinkers argued that liberty required institutions capable of restraining arbitrary power. Niccolò Machiavelli’s Discorsi (1531) held that only a populace able to check elites could remain free. James Harrington’s Oceana (1656), written during England’s brief republic, helped articulate the link between independence and ownership. In the American and French revolutions, republican ideas became state-forming principles: Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract (1762) radicalised demands for popular sovereignty, while John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and the authors of The Federalist Papers (1787-88) argued that only constitutional checks and balances could secure freedom.

James Harrington’s Oceana (1737 edition). Courtesy of the University of Alabama, Rare Books Collection

Economic republicanism in the 19th century applied these older concerns to the new industrial economies of the West. Its ideals shaped some of the era’s most important political and social conflicts: driving British trade unionists to fight for collective bargaining and shorter hours, energising the revolutions of 1848, and propelling land reform and anti-monopoly struggles later in the century.

To make sense of the term ‘economic republicanism’, it helps to understand how the long history of republican political theory views power. This goes back to the world of classical Greece and Rome, and was not always necessarily anti-monarchical. Its deeper commitment is to society organised as a res publica – a public thing – so that power is regulated in such a way as to secure the liberty of its citizens. As scholars such as Quentin Skinner, Philip Pettit and others have shown, republican liberty is best understood as the absence of domination. A person is unfree whenever they live at the mercy of another’s will without effective recourse. What compromises liberty and leads to unfreedom, republicans believe, is not direct interference in a person’s actions, but exposure to arbitrary power: a slave with a benevolent master remains unfree.

For republicans, self-rule is indispensable to liberty. Only when ordinary people have a meaningful part to play in governing are they no longer simply dependent on the goodwill of others. Self-rule transforms individuals from subjects of another’s domination into co-authors of the common world.

The liberty of early modern republicans rested on the unfreedom of others

Classical and early modern republicans described domination in terms of imperium and dominium. Imperium was arbitrary public power, the capacity of kings, ministers, governors to command without the consent of the people. Dominium, arbitrary private power, was the authority that owners, husbands, fathers, masters and later employers wielded over those dependent on them. Significantly, as the political theorist Camila Vergara observes in Systemic Corruption (2020), early modern republicans were often elitist defenders of liberty in the state but of hierarchy in society.

Landowners, merchants and slaveholders pressed for limits on royal authority while defending their own private domination. Their liberty rested on the unfreedom of others. For these powerful men, property – especially land, and with it control over those who worked it – was what entitled them to political authority. It secured their independence, signalled that they could govern ‘responsibly’, and ensured they would not themselves be subject to arbitrary public power. By the same logic, those without property were denied political rights.

In contrast, popular republicans insisted that the political process should be open to the propertyless, though usually they excluded women and Indigenous and enslaved people. From the 17th century onward, groups such as the Levellers, the Jacobins, and the early Chartists sought to expand the constitutional republic. However, they left the social and economic order largely intact. Yet the principle of freedom that constitutional republicans invoked contained a deeper logic than many realised.

Nineteenth-century economic republicans grasped the tradition’s long-standing association of economic and political power. Radically, they sought to universalise both. In making the positive case for doing so, they enlarged the republican critique of domination, extending it from the constitutional to the economic sphere.

If what makes a person unfree is dependence on another’s will, then private dependence is, they argued, as corrosive as public dependence. A worker who can be dismissed at will, a tenant without security, a debtor bound to a creditor – each lives under a structure of subordination akin to that of subject to prince. The object of republican suspicion was therefore no longer only the king, the minister or the standing army. In the new industrial societies of the West, it was also the factory owner, the manager, the monopolist, the creditor and the large landholder. The arbitrary exercise of economic power was, for economic republicans, unmistakably a form of domination. A constitutional republic that left this untouched was, in their eyes, an unfinished republic.

A fully realised republic required the dismantling of arbitrary economic power and the construction of institutions through which people could govern their economic lives. Yet economic republicans did not seek salvation in an all-powerful state; they regarded public despotism with the same suspicion they directed toward private authority.

Hodgskin declared that ‘capitalists’ had displaced the ancient aristocracy

While their views on whether market competition could best secure self-rule diverged, they agreed on the central point: that popular economic self-government required freedom from both imperium and dominium. Although historians have noted republican strands within 19th-century socialism, they have not recognised these writers as participants in a single, century-long conversation with pro-competition writers, focused on the shared problem of limiting arbitrary power in both its public and private forms.

The later 20th-century habit of framing politics in terms of ‘state’ versus ‘market’ has obscured this inheritance. Despite their disagreements, economic republicans were a single tradition united by a common project: the diffusion of power for popular ends and the creation of economic institutions capable of sustaining self-rule.

We can see this in the work of just some of them: Thomas Hodgskin (1787-1869), John Francis Bray (1809-97), Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-65), Jeanne Deroin (1805-94), Henry George (1839-97) and Henry Hyndman (1842-1921).

The former Royal Navy officer Thomas Hodgskin was among the first to identify that a new ruling class had emerged. A key figure in the foundation of the Mechanic’s Magazine in 1823, as well as the first mechanics institutes, bastions of working-class self-education, he declared that ‘capitalists’ had displaced the ancient aristocracy. The struggle for freedom, he argued, was no longer against kings or nobles but against employers who claimed the right to command labour.

The frontispiece to Mechanic’s Magazine, volume 1, 1823. Public Domain via historyofinformation

Hodgskin, a disciple of Adam Smith, was in many ways an anti-establishment market libertarian. Genuine competition – free from monopoly and privilege – would, he believed, enable workers to cooperate as independent producers. A free economy, properly constituted, would resemble a network of self-governing associations rather than a hierarchy of masters and servants. His vision inspired the early cooperative movement and the radical artisans who saw in production itself the foundation of citizenship.

John Francis Bray likely encountered Hodgskin’s ideas at the Leeds Working Men’s Association where he gave a lecture course. A native of the United States, Bray was a self-taught printer and later a farmer; he proposed a ‘Republic of Labour’, a federation of cooperative workshops linked by local councils. Each worker would own personal property but pool resources into ‘joint-stock’ associations, coordinating production and exchange through democratic planning.

Bray’s model rejected both capitalist competition and bureaucratic control. Economic coordination, he believed, should be an act of citizenship – people governing their common life together. Economic planning was not technocratic but republican: it was the process by which a free people could make collective decisions about their material future. On his return to the US, Bray would remain a significant figure within economic republicanism. He was a vice-president of the American Labor Reform League; when he joined the Knights of Labor, they named their assembly in Pontiac, outside which he resided, after him. At the end of his life, he was also associated with the Populist Party.

The upheavals of 1848 in France carried economic republican ideas from radical theory into open politics. The anarchist printer and philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that a political revolution without an economic one was hollow. While initially inspired by Bray’s proposals for labour notes and equitable exchange, Proudhon soon moved beyond them. In 1848, he proposed a Bank of the People that would provide interest-free credit to workers’ associations, enabling collective ownership and control of production. His aim, as he put it, was to ‘republicanise specie’, to make finance itself an instrument of economic self-rule rather than private domination.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon photographed in 1900 by Nadar. Courtesy of the BnF, Paris

Though short-lived, this experiment in mutual credit marked Proudhon’s most original contribution to economic republicanism. He extended the principle of self-government into the monetary sphere, insisting that credit, like the republic itself, must belong to all and be governed by those it binds. The idea outlived the institution, shaping later cooperative and mutual banks and the broader conviction that freedom requires not only political rights but economic sovereignty.

The feminist and socialist Jeanne Deroin, a seamstress, teacher and journalist, took republicanism in a new direction. Though inspired by Proudhon, she met only his contempt; her insistence on women’s equality and her 1849 bid for election to the Legislative Assembly offended his deeply held misogyny. The authorities invalidated her candidacy, but by then she had already made her most significant intellectual contribution to economic republicanism.

Deroin’s Fraternal and Solidary Association of All Associations envisioned a proto-syndicalist commonwealth uniting producers and consumers in a single democratic federation. Each member would, she wrote, ‘by voting on its budget … sanction the operations of the Central Commission and enshrine the principle of popular sovereignty.’ Freedom, she insisted, required the inclusion of all who contributed to social life; women, children, the sick and the elderly, as well as industrial workers. Economic democracy was not only a matter of production but of universal participation: a republic in which the dependent and the excluded were recognised as citizens of the social whole. Exiled to London after the Bonapartist reaction, Deroin formed a bridge between the revolutionaries of 1848 and the emerging socialist and feminist movements of the later 19th century.

For Hyndman, centralised state planning was no substitute for popular power

A third generation of economic republicanism emerged in the work of the American reformer Henry George. Writing amid the inequalities of the Gilded Age, George revived the republican connection between property and power. His book Progress and Poverty (1879) sold millions, making him the most widely read economist during the 19th century. A self-taught printer turned journalist, he argued that the private monopoly of land was the root of social domination. ‘To say that the land of a country shall be owned by a small class,’ he warned, ‘is to say that that class shall rule it; … republicanism is impossible.’ He proposed a single tax on unearned land values to return the rents of nature to the community, reconciling public and private property, cooperation and competition. Individuals could hold land, but the increase in its value, created by collective activity, would be reclaimed for the common good, dispersing power so that no class could rule another. While George advocated cooperative enterprise, he held that it could thrive only in a fair competitive order.

Undated photograph of Henry George, author of Progress and Poverty. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

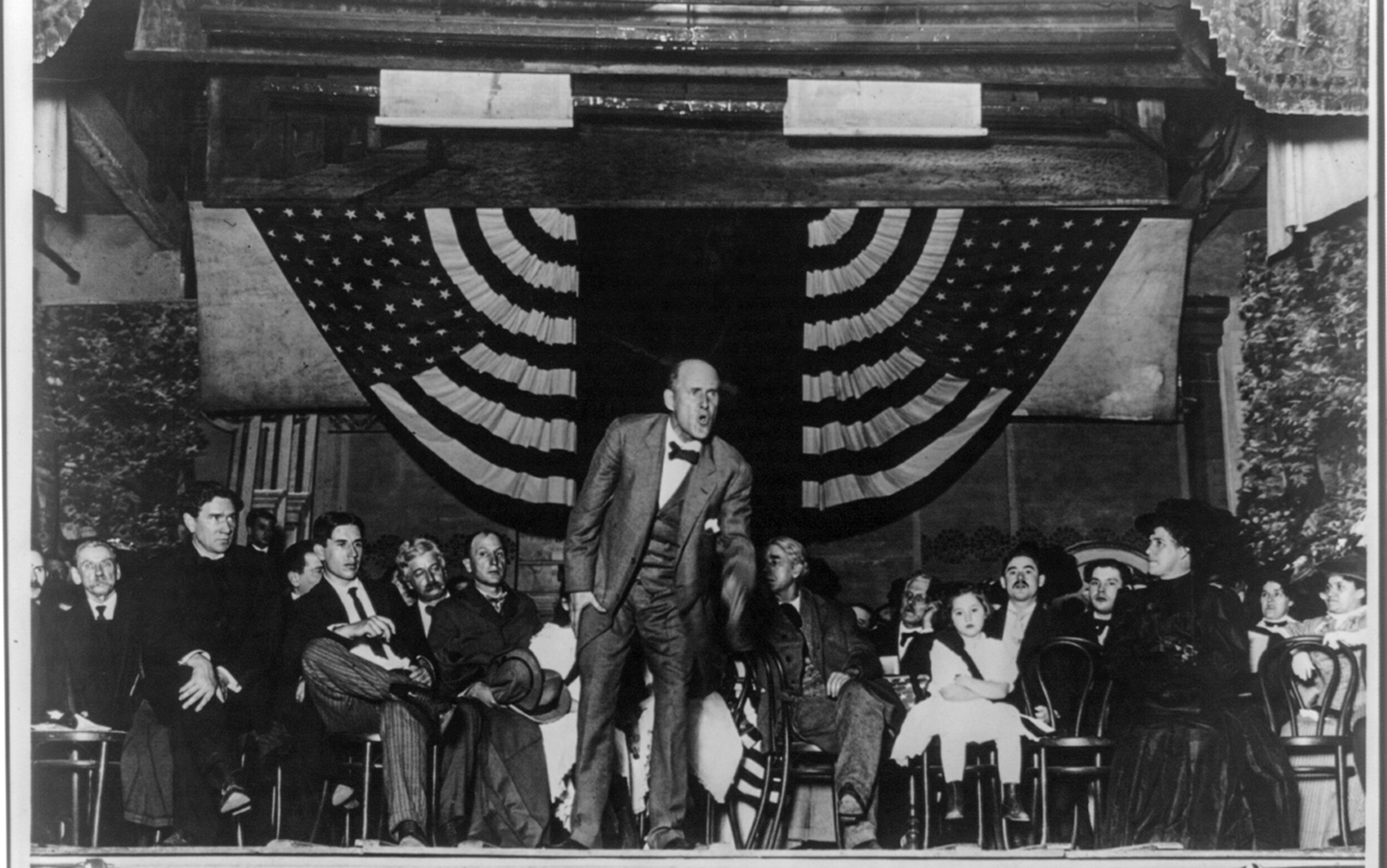

George’s ideas made him a global celebrity of reform and twice a candidate for mayor of New York City, where he campaigned for land reform and democratic renewal. Though defeated, his movement helped inspire the Progressive Era. Its most concrete, if incomplete, legacies can be found in Singapore and Hong Kong, where public capture of land rents funds housing and infrastructure. Today, amid mounting housing crises and renewed calls for wealth and windfall taxes, his work holds fresh appeal.

The Irish Land crisis was pivotal to George’s intellectual development, and his ideas resonated throughout the British Empire. Among those most influenced was Henry Hyndman, founder of Britain’s Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and one of the first to translate Marxism into English political debate. Hyndman hailed George as a kindred spirit, and the two briefly collaborated over the issue of land nationalisation before parting ways. Hyndman’s socialism was distinctively republican. ‘A great democratic English Republic,’ he wrote in 1884, ‘has ever been the dream of the noblest of our race … To bring about such a Republic is the cause for which we Socialists agitate today.’

For Hyndman, centralised state planning was no substitute for popular power. Socialism, as he conceived it, required the decentralisation of both political and economic authority. Factories, councils and local associations were to be governed by those who worked within them; equality without self-rule, he warned, would merely reproduce subordination. Through the SDF, Hyndman helped institutionalise a republican socialism that made the economy itself a site of citizenship. His influence reached the Labour Representation Committee, out of which emerged the Labour Party in the UK.

Across Britain, France and the US, these thinkers formed what can now be seen as a coherent, if internally divided, republican tradition. Though they differed over whether market competition could serve as a context for freedom, they shared a conviction that economic dependence, whether on boss or bureaucrat, was intolerable. Each built upon the other’s insights, carrying forward the shared problematic of economic republicanism: how to limit both imperium and dominium, and establish popular rule.

By the 20th century, economic republicanism’s language of power had been displaced by new political vocabularies. The social-democratic Left, as the direct heir of the republican tradition, exchanged its commitment to liberty and self-rule for the pursuit of equality. In doing so, it came to believe that freedom could be secured through the agency of the state and its experts; an ambition at odds with the republican ideal of popular power.

Much of the social democratic vision was realised after 1945: the welfare state, public education, national health systems and strong trade unions. The result was significant material progress for working people. Yet as living standards rose, the republican ideal of popular economic power receded. Citizens gained security but not agency; the structures that delivered prosperity often deepened their sense of powerlessness.

By the 1970s, the tension between material improvement and social impotence had become impossible to ignore. Frustrations long contained by growth broke into the open amid deindustrialisation and stagnation. Movements for worker self-management, codetermination and cooperative ownership briefly revived the republican spirit. Yet with social-democratic parties unwilling to reclaim their founding radicalism, the political Right seized the language of autonomy for itself, recasting the demand for popular power as the language of popular individualism. It was this transformation that paved the way for neoliberalism and the long unravelling of social democracy’s achievements.

Increasingly, public and private forms of domination do not stand apart but act in alliance

Restricting republican concerns to the realm of politics was always a political choice, one imposed and maintained by economic elites. The result is the pervasive sense of powerlessness marking our current politics, and the authoritarian turn it has produced.

Consequently, this absence of economic self-government not only fuels discontent; it also enables the consolidation of new forms of arbitrary rule. On the public side, expanding security states and unaccountable bureaucracies exercise power with little democratic constraint. On the private side, workplace protections are rolled back, gig-economy precarity spreads, and platform firms manipulate millions through opaque algorithms. Increasingly, these public and private forms of domination do not stand apart but act in alliance, a fusion of imperium and dominium.

The principle that guided the 19th-century economic republicans, the conviction that liberty requires power over the conditions of one’s life, has never been more urgent. Our constitutional republics can survive only if they are completed by economic republicanism. As the tradition tells us, only economic power can secure political power.

What might this look like in the 21st century? Just a few key features can be set out here.

Economic self-rule would require:

- Democratic firms, where workers and communities share ownership and decision-making.

- Public and cooperative finance, treating credit as a civic resource rather than a private monopoly.

- Transparent digital infrastructures, governed as public utilities and open to democratic oversight.

None of this can be achieved in a single leap. Rather, every reform that moves us toward shared control over the basic structures of economic life is a step toward freedom.

Reversing oligarchy and resisting authoritarianism will require building a new democratic economic order. The 19th century’s economic republicans can guide us, but the task today is not to resurrect their programme; it is to craft an economic republicanism fit for our own age. Critically, we must reject the binary of ‘state’ and ‘market’ and find combinations of competition and coordination that work for us. Such a project offers a route toward genuine popular power and real individual freedom. We must complete the republican project.