Alongside equality, freedom and opportunity, fear has long played a powerful role in political discourse. In ordinary life, fear is often a fitting response to danger. If you encounter a snake while out on a hike, fear will lead you to back away and exercise caution. If the snake is poisonous, fear will have saved your life. By contrast, the fears that dominate political discourse are less concrete. We are told to fear elites, terrorists, religious zealots, godless atheists, sexists, feminists, Marxists and the enemies of democracy. Yet even as these purported poisons are less obviously lethal, political rhetoricians have long understood that making them salient is a powerful way to shape citizens’ motivations. As Donald Trump told Bob Woodward: real power is fear.

It is tempting to think that political fear is largely manufactured – a cynical ploy to manipulate the masses. Trump’s dark vision of the United States would seem to be a prime example of this. Yet, fear can be fitting in politics. Citizens face real dangers from failed political leadership, as lethal to our livelihood as snake bites.

Thomas Hobbes, the 17th-century political philosopher, understood fear. Hobbes was born in 1588 in the English town of Malmesbury, during the Anglo-Spanish war. As rumours of an impending Spanish attack circulated, he described his mother as ‘filled with such fear that she bore twins, me and together with me fear.’ Fear would follow Hobbes throughout his life. England in the 17th century was torn apart by religious and political factions, recurring plagues, misinformation, inflation and a changing labour market. Like in our current moment, pessimism and uncertainty ran rampant. As Jonathan Healey notes in his fantastic book on this period, The Blazing World (2023), the parallels between these historical periods are not hard to find: ‘We, too, are living through our own historical moment in which a media revolution, social fracturing and culture wars are redefining society and politics.’

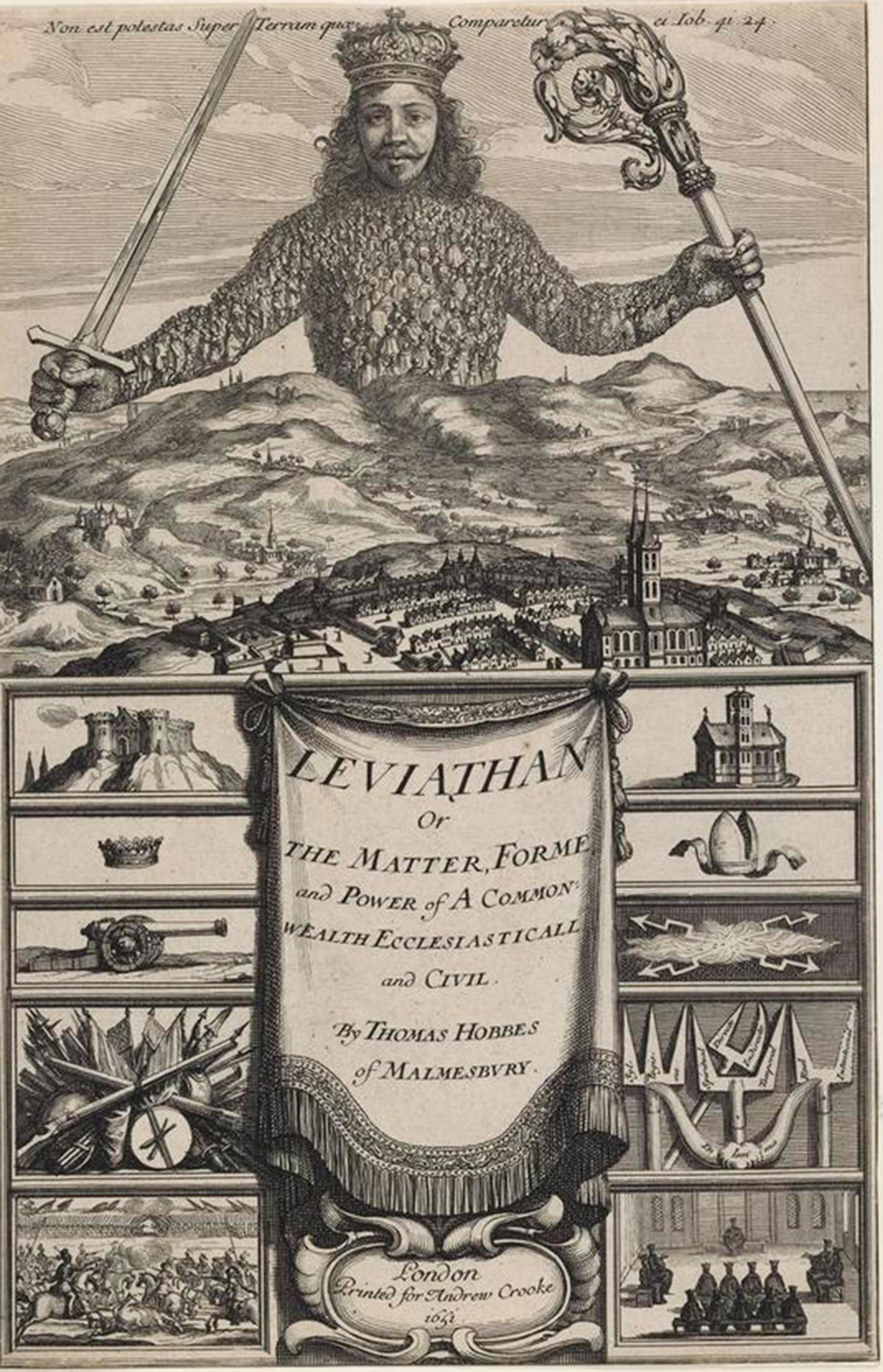

Frontispiece of Leviathan (1651) by Thomas Hobbes, engraved by Abraham Bosse. Public domain

Many dismiss Hobbes as a curmudgeon whose argument for authoritarianism was guided by his view that people are naturally selfish and violent. In Leviathan (1651), his most influential book, he argues that, without a powerful executive in absolute control, we would lead lives that are ‘nasty, brutish, and short’. He also seems to suggest that, once that sovereign is established, we have no right to rebel against it since the alternative is invariably worse (though commentators disagree on whether this is a fair interpretation).

We have good reason to reject the view that even the most horrific authoritarian regimes are always better than the chaos brought about by rebellion. Stability is not the only political value. But we have lost sight of how important it is. And though we certainly should reject Hobbes’s most extreme authoritarian conclusions, there is much we can learn from understanding the motivations that led Hobbes to accept them, particularly in this current moment in which the appeal of authoritarians like Trump is ascendant.

On the Hobbesian picture, fear is a fitting response to instability and insecurity. As Hobbes describes in one of the most influential passages in political philosophy, ‘wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them’, there is no point in hard work, because the results of it are uncertain. You might work hard to build a home or start a business, only for it to be taken from you by someone who finds a way to do so through strength or cleverness. And, as Hobbes argues, if the connection between our effort and the fruit of that effort is severed by uncertainty and instability, then so much of what we value loses its point. Without security there is ‘no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society.’ Instead, Hobbes suggests, we live in a state of continual fear.

It is not hard to see why insecurity about the future diminishes our lives. A dental emergency or a stolen catalytic converter might wipe out your savings. Inflation can turn a budget teetering on the edge of affordability into a financial emergency. When you are living in precarity, planning seems futile. Inflation, a rental increase or a medical emergency can leave you feeling a fool, with your plans and little else to show. Security is the foundation for much of what makes our lives worth living.

Like in the tumultuous period in which Hobbes wrote, far too many people currently face various sources of insecurity and instability. The 2023 report on the economy by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences finds that many Americans cite financial uncertainty and precarity as a central concern. The Starbucks worker who has no idea when their shift will be, how many hours they will work, or whether they will be able to keep their job is in a state of insecurity that makes it hard to plan for the future. And even if you are feeling flush today, workers are increasingly working jobs without guarantees against being fired from one day to the next, or of being able to afford retirement. Almost half of private-sector employees in the US do not have the option of saving for retirement through work.

The US is the only developed nation in the world to have the phenomenon known as ‘medical bankruptcy’

Inflation is also a source of insecurity. When you cannot know whether you can afford tomorrow what you can afford today, you are not certain how far your salary will go, even if you feel sure you will remain employed. Your life feels increasingly tenuous when your expenses multiply from one month to the next. Historically, Americans have purchased homes to protect themselves against rising housing costs, increasing rents and eviction. However, for younger Americans, owning a home has become a dream rather than a plan.

Housing costs have become one of the principal complaints of citizens across the wealthiest countries. Gallup has found that, in OECD countries, half of respondents are dissatisfied with the availability of affordable housing. Only 10 per cent of US adults surveyed by a Wall Street Journal/NORC poll in July 2024 said homeownership was easy to achieve, though 89 per cent thought it essential to their future. Furthermore, half of all renters in the US spend more than 30 per cent on rent and are classified as ‘cost-burdened’, according to a recent report by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University.

Healthcare costs are also a concern for many. The US is the only developed nation in the world to have a common phenomenon known as ‘medical bankruptcy’, and it is the leading cause of bankruptcy for Americans. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service has suffered under decades of austerity economics. And, of course, the threat of climate change looms over all our lives. In many parts of the developing world, its devastating effects are already taking lives, destroying homes, and turning existence itself into a perilous proposition. After a brief pandemic blip, the safety net is in tatters in the US, and in the UK nearly a third of children live in poverty.

An economic system that values market efficiency over creating security and stability erodes the central planks of our lives – work, home and health.

Even if you are lucky enough not to experience these sources of insecurity yourself, it is rational to fear the possibility when you see it happening to those around you. What Hobbes understood is that instability and insecurity ripple through our social world undermining the lives even of those who haven’t been directly affected. If my neighbour’s insurance refuses to cover the damage his house sustained during an unprecedented storm and my friend’s insurance bill has wiped out her savings, my position starts to feel less secure. And when instability and insecurity take hold of the citizenry, the political project is in peril.

Many have interpreted Hobbes as a ‘law and order’ philosopher primarily concerned with political infighting and civil war. However, unpacking the historical context in which he was writing allows us to see that political instability was but one factor in a broader set of conditions to which Hobbes was responding. The English economy transitioned from feudalism to a market-based system during this period. The face of poverty changed from one of serfdom in the countryside, where at least one could count on room and board, to wage poverty in cities where homelessness and starvation were real threats. The very real precarity facing what we would now call the working class was a critical factor.

In Leviathan, Hobbes draws an extensive metaphor between the body politic and literal bodies to warn against the various diseases that can lead to the dissolution of the commonwealth. He writes that:

[T]here is sometimes in a Common-wealth, a Disease, which resembleth the Pleurisie; and that is, when the Treasure of the Common-wealth, flowing out of its due course, is gathered together in too much abundance, in one, or a few private men, by Monopolies or by Farmes of the Publique Revenues; in the same manner as the Blood in a Pleurisie, getting into the Membrane of the breast, breedeth there an Inflammation, accompanied with a Fever, and painful stitches.

This inflammation – massive inequality of power and wealth – breeds the instability and insecurity that characterise Hobbes’s historical period and resonate so much with our own.

If enough people stop trusting that this system works, we are, as Hobbes would put it, in a state of ‘warre’

For Hobbes, much like the fear of a poisonous snake should lead us to tiptoe away from danger, the rational response to the fear of insecurity is to seek its opposite: stability and security. Without it, we lose the precondition that makes so much of what we value – education, culture, industry, community – possible. Hobbes argues that it is rational to sacrifice many of our freedoms to achieve such stability and security. Those freedoms are, after all, entirely pointless if we are in conditions where we cannot enjoy them.

Political society is meant to solve this problem by protecting us against uncertainty and insecurity so we can lead our lives looking forward, rather than in a heightened state of anxiety about how to make it through today. The problem we face is that there are many people for whom the system of government doesn’t offer protection from daily insecurity and instability. And if enough people stop trusting that this system works better for them than the alternative, we are, as Hobbes would put it, in a state of ‘warre’.

At a rally in Virginia in June 2024 after the disastrous first debate of the latest election season, Trump said: ‘As every American saw firsthand last night, this election is a choice between strength and weakness, competence and incompetence, peace and prosperity, or war or no war.’ Carefully crafting the choice as one between the security that comes from strength and competence, and the insecurity that comes from weakness and incompetence, Trump again reinforced his message. If you don’t choose me, your lives will get only more insecure and uncertain. And after he was the target of an assassination attempt, he reinforced this message by emerging, fist pumping in the air – a picture of strength in the face of chaos.

Trump’s proposed solution is authoritarianism (as he said in 2016: ‘I, alone, can fix it’). The problem with this solution is that it ends up trading one source of insecurity – our fractured political system – for another – the whims of an individual whose principal interest is his own power rather than the wellbeing of the body politic. But even if we reject this solution as flawed, we cannot dismiss the concerns that drive many to consider it. The democratic party has a new candidate now, but it isn’t clear whether Kamala Harris and Tim Walz’s policies will address the need for security and stability.

Hobbes was wary of democracy precisely because he thought it would lead to instability and insecurity. Competing factions and groups would undermine the system’s stability by vying for power. Hobbes argued that stability is to be found in consolidating power into the sovereign and in the compliance of the governed. However, we cannot forget that for Hobbes, as for other social contract theorists, compliance is earned, not demanded.

Democratic liberal states have rejected authoritarianism as the solution to the problem of insecurity, preferring to emphasise the benefits of living in a state where our wellbeing is safeguarded by the enshrinement of our freedom into laws and institutions. Stability is meant to be the product of citizens’ acceptance of the shared values at the heart of liberalism. But does this compact guarantee the material security and stability that are preconditions for flourishing lives? For the millions who worry about whether they can afford their grocery bill, rent or medical expenses, the answer appears to be no.

Nostalgia’s power is most potent when no compelling, believable vision of a brighter future exists

The COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath offered a glimpse of a solution. When things felt precarious and uncertain, the US government stepped in with eviction moratoriums, universal basic income, free vaccines and a child tax credit. (Let’s not forget that Trump made sure that those stimulus checks bore his name.) But a few short years later, we are back to business as usual, leaving millions on the edge of precarity.

This is not to deny that xenophobia, sexism and racism also churn through the current discontent with liberalism. Nostalgia for times past is a strong undercurrent of the appeal of Right-wing movements. Some want the return of the well-paid factory job with strong benefits, while others want a return to white male supremacy. But nostalgia’s power is most potent when no compelling, believable vision of a brighter future exists.

Those who fear Trump’s re-election and the rise of Right-wing political movements keep reminding us that democracy is on the line. But sowing fear and doubt only adds to the growing sense of insecurity and uncertainty that is already unravelling people’s trust in the liberal project. It plays right into the hands of the strategy that Trump is so adept at playing. For people to see the value in the current system, we need to do more than fear-monger about the alternative.

Hobbes is often interpreted as being narrowly focused on justifying a powerful state that could control our worst appetites so as to prevent us from killing each other. I have argued that if we take his concern for stability and security seriously, the solution requires a far more radical rethinking of liberal states as they currently exist. Material insecurity and political instability cannot be divorced. A liberal state that leaves so many feeling as if their lives are on the verge of being ‘nasty, brutish, and short’ falls short of solving the problem that political society is meant to solve. Freedom is meaningless if you cannot count on a stable connection between the work you put in today and a good life tomorrow. But this is precisely the connection that has become severed for so many. If political society is to enable flourishing lives, then we need a political and economic system that can provide that kind of stability. This requires more than mere rhetoric. If we fail, Leviathan is waiting in the wings.