As a boy, growing up in a small town in the south-east of England, I found little to nourish me when I questioned my gender; there was nothing on such issues in our local library and no discussion of it at school. I used to scour the TV listings and the newspapers, desperate to find anyone with the same issues as me, and learn how they handled them. In films and documentaries, and in articles that tried to explain transsexual lives, I kept seeing the same stories: people who ‘always knew’ that they were ‘born in the wrong body’, and who had to choose between being themselves or risk their family and friends disowning them. I soon tired of them. However, one thing about these articles struck me every time: the ‘before and after’ photographs.

I remember one article in a women’s magazine about someone who was ‘Born a Man’. At the time, I didn’t think about how stupid this phrase was: I was too dazzled by the photographs of a person reclining, her palm resting where her forehead met her long, blonde hair. ‘Now I’m a Beautiful Woman!’ screamed the headline. Clearly, the photographs were the story. In her past, the woman looked like any boy, neither exceptionally attractive nor unattractive. Now, she could have been a model. I didn’t care: although I knew deep down that I wanted to be a woman, I had no interest in fashion, and I soon realised that this article wasn’t for me.

In the Sunday People, I saw an ad for a company called Transformation. ‘From He To She … Instantly!’ it promised, above photos of a stubbly, balding man and a glamorous woman in heavy make-up, brunette wig and pretty dress. It was designed to sell feminising products to male-born people who cross-dressed or were transsexual. I was skeptical about what they sold to stop facial hair growth or to develop a bust, thinking this would require more than some miracle cream or stuffing something inside a bra. The ad seemed like it came from another world; yet it made me feel that transition might be possible, even if I still didn’t really know how.

The adult me, cannier and more cynical, can see that ‘before and after’ photographs have the strange effect of masking the process of change even as they appear to reveal it. I still see the ruse all the time, in the same tabloids that my parents read during my teens, notably the Daily Mail. And it’s a stalwart on pop culture websites, the main weapon in both malicious attempts to undermine someone’s identity, as well as seemingly sympathetic articles. Recently, the shortcomings of ‘before and after’ were exposed when a number of high-profile transsexual people, such as American actress Alexis Arquette, Chaz Bono (child of Sonny and Cher) and Hollywood film director Lana Wachowski, came out. With Arquette in particular, who was constantly in the public eye, and whose film roles include a memorable performance as the young cross-dresser Georgette in Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989) — there was no point in trying to pretend that she had changed overnight; so instead of trading on ‘before and after’, media outlets studied old images for gradual movement, scanning for any ‘signs’ they had missed.

Makeover TV shows such as 10 Years Younger or What Not to Wear also rely on the trope of dramatic and instantaneous change. Admittedly, these demonstrate more of the transformative processes, but still implying that all will be perfect once they are completed, making outer appearance and inner peace synonymous. What happened to their subjects once the cameras go away?

The rise of reality TV shows has made this question all the more visible, including for transgender contestants. Big Brother, in particular, made a near fetish of featuring outsiders, presumably in the hope that they would clash with each other. It had the surprising effect of normalising transgender people, while catapulting them to sudden fame. In 2004, the trans woman Nadia Almada won Big Brother, and in 2012 trans man Luke Anderson triumphed. Neither had told their housemates about their pasts, but revealed them to the public instead. Their victories made them into transgender role models, and the internet gave them longevity, creating a strange new middle ground in the old obscurity-celebrity-obscurity narrative.

‘Before and after’ pictures have been part of print coverage of transsexualism from the start. In January 1937, less than a decade after the earliest sex reassignment surgeries were performed in Berlin, the American bodybuilding magazine Physical Culture ran one of the first articles on the subject, entitled ‘Can Sex In Humans Be Changed?’ Its opening paragraph was surprisingly relaxed about the possibility of radical social change, suggesting: ‘The old landmarks are going, nothing is static, everything flows … Life is created in the laboratory [and] Sex is no longer immutable.’ The writer, Donald Furthman Wickets, went on to look at historical ideas of ‘male’ and ‘female’, and the role of hormones in determining them.

The article was accompanied by two shots of Britain’s first surgically transsexual man, Mark Weston: one of him posing in a white shirt, tie and tank top with Alberta Bray, ‘a former girl chum to whom he is now married’; the other as ‘the late Miss Mary Weston, Great Britain’s girl [javelin] champion’ during the 1920s. The only clear difference between the two was that he had grown some stubble. There was also a single image of Zdenek Koubkov of Czechoslovakia, who’d won the women’s 100m at the 1932 Olympic Games as Zdeneka Koubkova, but who had since transitioned, and was shown wearing a suit and lifting his hat to show off his closely-cropped hair. The pronouns ‘he’ and ‘him’ were used throughout, and readers were offered little sense of what happened physically to the athletes. In both cases, they were told: ‘The miracle was accomplished by surgery and duly acknowledged by law.’

Weston and Koubkov did not become international news. It was only after the Second World War, as photographs on newspaper covers became commonplace, that transsexualism developed into a mass media phenomenon. On 1 December 1952, the New York Daily News ran the sensational story of Christine Jorgensen under the headline ‘Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty’ – with contrasting images of her as a male soldier, then glamorous woman, dominating the spread. Instantly, Jorgensen became a celebrity, working as an actress, singer and transgender rights advocate.

It wasn’t just gender roles that were in flux, but gender itself. What would happen if men could become women, and vice versa?

In Transgender History (2008), Susan Stryker claims the fascination with Jorgensen ‘had to do with the mid-20th-century awe for scientific technology, which now could not only split atoms but also, apparently, turn a man into a woman’. Stryker, a professor of gender studies at the University of Arizona, also notes that Jorgensen was the first American transsexual woman to become prominent after the war changed women’s relationships with paid labour and domestic work. It wasn’t just gender roles that were in flux, but gender itself.

As it transpired, The Transsexual Phenomenon (as the sexologist Harry Benjamin called it in his influential 1966 book) did not destroy US society. Or even visibly change it. Looking at the New York Daily News photographs of Jorgensen now, they come nowhere near to justifying their attention-grabbing tag – ‘Operations Transform Bronx Youth’. Jorgensen’s facial structure, her hairline, eyes, nose and chin, barely altered between 1943 and 1952: the main differences were her clothes and make-up.

While magazines like Physical Culture and the New York Daily News, were modelling a radical discontinuity between ‘male’ and ‘female’ and emphasising the otherworldly, even anarchic, intentions of those crossing them, sexologists, feminists and gender/queer theorists were exploring the space between these categories and suggesting that it was here that behavioural expectations for men and women were socially generated. The writers I liked most argued that the very possibility of gender re-assignment meant there wasn’t as much difference between the sexes as was once thought. By the late 1980s, Sandy Stone’s seminal essay ‘The “Empire” Strikes Back: A Post-Transsexual Manifesto’ was calling for transsexual people to be open about the space between male and female identity, and how they moved within it. This is the space that ‘before and after’ pictures keep hidden in order to retain their power to humiliate and shock.

I spent my late teens and early 20s exploring my gender. I read essays and books, and watched many more films that featured transgender characters and even, sometimes, transgender actors. I wore women’s clothes at home and to clubs and bars, trying out different styles to see what felt comfortable, and talked to people who asked whether or not I wanted to ‘go all the way’. Eventually, in March 2009, I decided that I did, and asked my doctor about gender reassignment through hormones and surgery.

I didn’t expect the sort of rapid transformation I’d seen advertised in my youth, and I wasn’t surprised to learn that from start to finish the process would take about three years, partly due to waiting times for specialised services. Nor was I shocked when told that the physical changes would not transform me beyond quick recognisability, as they had not transformed Weston or Jorgensen. Instead, they’d form part of a longer psychological process; altering my body in a society with entrenched ideas about how men and women should appear and how they should be treated, meant rethinking how I dressed, spoke and moved, where I went and with whom, and how I felt about myself.

Like Sandy Stone, I decided to document the time it took to move, in what became my transgender journey blog for The Guardian (it ran from June 2010 to November 2012). I hoped to create something between those one-off ‘transition narrative’ articles, which seemed to have barely evolved since the 1990s, and transsexual autobiographies such as April Ashley’s Odyssey (1982), which for years were the only way people could explain what happened at any meaningful length.

Even without make-up, my face suddenly looked more female than ever before. I realised that nobody had heckled me on the street for being transsexual for months

Ashley’s memoir, co-written with Duncan Fallowell, documented her voyage from the post-Depression Liverpool slums of the 1930s to national fame in the 1960s. There were spells in the Merchant Navy and as a performer in a Parisian cabaret, surgery in Casablanca, an acting and modelling career hampered by tabloid revelations, and a marriage to Arthur Corbett, Lord Rowallan, later annulled on the grounds that she was ‘a person of the male sex’. That her beauty came with a transsexual history was central to her celebrity, yet the path from photos of ‘George Jamieson, aged 15, at school’ to ‘Toni April, aged 21’, and finally April Ashley in the early 1960s appeared not jarring but smooth and logical. Another British autobiography, Conundrum (1974) by Jan Morris, an established travel writer long before her transition, used no images at all — an approach I much preferred.

As a rebuttal of the implied instantaneity of ‘before and after’ photographs, I wanted my Guardian posts to cover the process in real time, but it was too slow: months passed between my appointments at the gender identity clinic, the hormone prescription took more than a year to arrive, and the effects of the oestrogen were gradual. Even allowing for the fact that my blog began a year after the medical pathway, I’d said all I wanted to say about the social and psychological aspects of transitioning long before I got a date for surgery.

One thing I did find hard to chronicle was the strange effect this all had on my sense of myself as a continuous subject. For many months, coming out and changing my name seemed like the major rupture: having people refer to me differently and treat me differently felt far more sudden than anything that later happened to my body. Besides, the hormonal effects were too subtle for me to see, so when friends said I looked different, I’d ask them to explain how. Their responses usually matched my expectations — thicker hair, softer skin, fuller cheeks.

After more than a year of despairing at how little impact the oestrogen seemed to have made, I undressed in front of a mirror and was astonished by my own appearance. Even without make-up, my face suddenly looked more female than ever before. I realised that nobody had heckled me on the street for being transsexual for months. Moreover, I’d developed breasts — smaller than the inserts I’d bought a couple of years earlier, which in hindsight weren’t well-judged, presenting too fast a change in my appearance, and they were too obviously prosthetic — but a visible and important change nonetheless.

At this point, I came across Becoming (2010), a flipbook by the Berlin-based artist Yishay Garbasz. She regularly photographed herself as a standing nude after starting gender reassignment, choosing 87 of the 911 pictures for her book, and installing 28 images as a zoetrope for the 2010 Busan Biennale in South Korea. Each picture was taken against a white backdrop, without make-up, emphasising the incremental changes to her frame. In this context, even her sex reassignment surgery in 2008 did not appear abrupt or incongruous, but was rather assimilated into the physical landscape she presented.

Like me, Garbasz had struggled to take control of the ‘before and after’ conceit, and expose the potentially limitless terrain contained within it. I still enjoy seeing it debunked. For example, I recently laughed at how easily the ‘dramatic weight loss’ juxtaposition was taken apart by an Australian personal trainer on her blog, MelVFitness. She showed how better posture, fake tan lotion and black bikini bottoms — as well as zooming in for the ‘before’ and out for the ‘after’ — enabled her to fake such a ‘radical transformation’ in just 15 minutes.

I’ve seen this demystification so often that I now find it strange to see such pictures in print — and never stranger than when I spotted someone I’d known by a male name at sixth-form college who’d become famous as a female model, with the newspaper spreads yet again screaming ‘before and after’. I recognised her from the opening catwalk shot long before I got to the image of her as a boy, or the story of her gradual self-realisation, which closely mirrored mine.

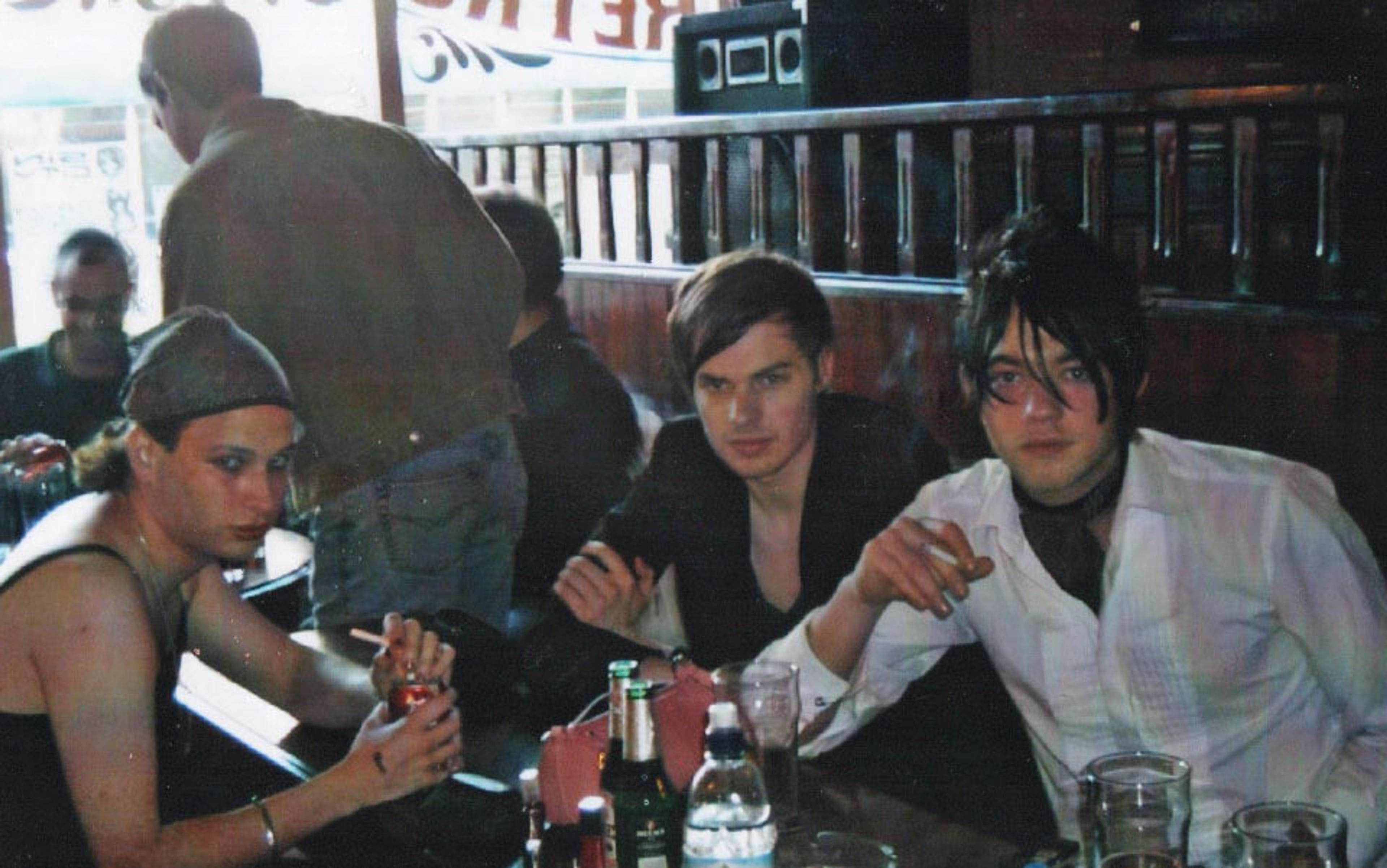

This took me back to a photograph of myself from 2004, which I stumbled across just after my body epiphany. It was taken in Manchester; I was pictured with two friends, Joe Stretch and Joe Cross, and wore a 1920s-style dress and a headscarf over my hair, with make-up hiding my skin texture. This find led to another kind of epiphany, which instantly closed the psychological gap between my pre- and post-transitional self, and highlighted the continuum between the various identities I’d grown into while exploring my gender. I realised that I could have easily faked transsexual ‘before and after’ pictures back then, if I’d wanted to, editing out the fact that, at the time, I presented mostly as male.

This autumn, 15 months after surgery, and finally feeling settled — like someone who had transitioned rather than someone who was transsexual — I let the American singer-songwriter Emily Forst, a keen amateur make-up artist, give me a makeover. She styled my hair and took a portrait that made me feel, for the first time since 2004, like the person I wanted to be. This came after years of dodging cameras — a hangover from the negative self-image attached to presenting as a man. Comparing the two photographs, the main differences I see are in my expression: my cautious optimism as a 22‑year‑old against the deep sadness in my thirtysomething eyes, having endured five years of street harassment, anxieties about how my loved ones would react to my transition, the physical pain of surgery, and the responsibilities that came with writing about it all.

I doubt that anyone who looks only at the before and after pictures of me would be able to see much of this. Although they would probably be better placed to tell me how my features had changed. But, really, that always struck me as the least interesting thing about my experience. And after everything that’s happened, it still does.