In my dreams, I walk like a normal person. I even run and skip. Sometimes I jump rope. I went through a whole series of diving dreams – making the perfect approach on the diving board, then the heavy step that vaults you into the air twisting and turning and performing a perfect forward dive with a double twist. I enter the water like a red-hot poker through ice cream. Toes pointed. No splash.

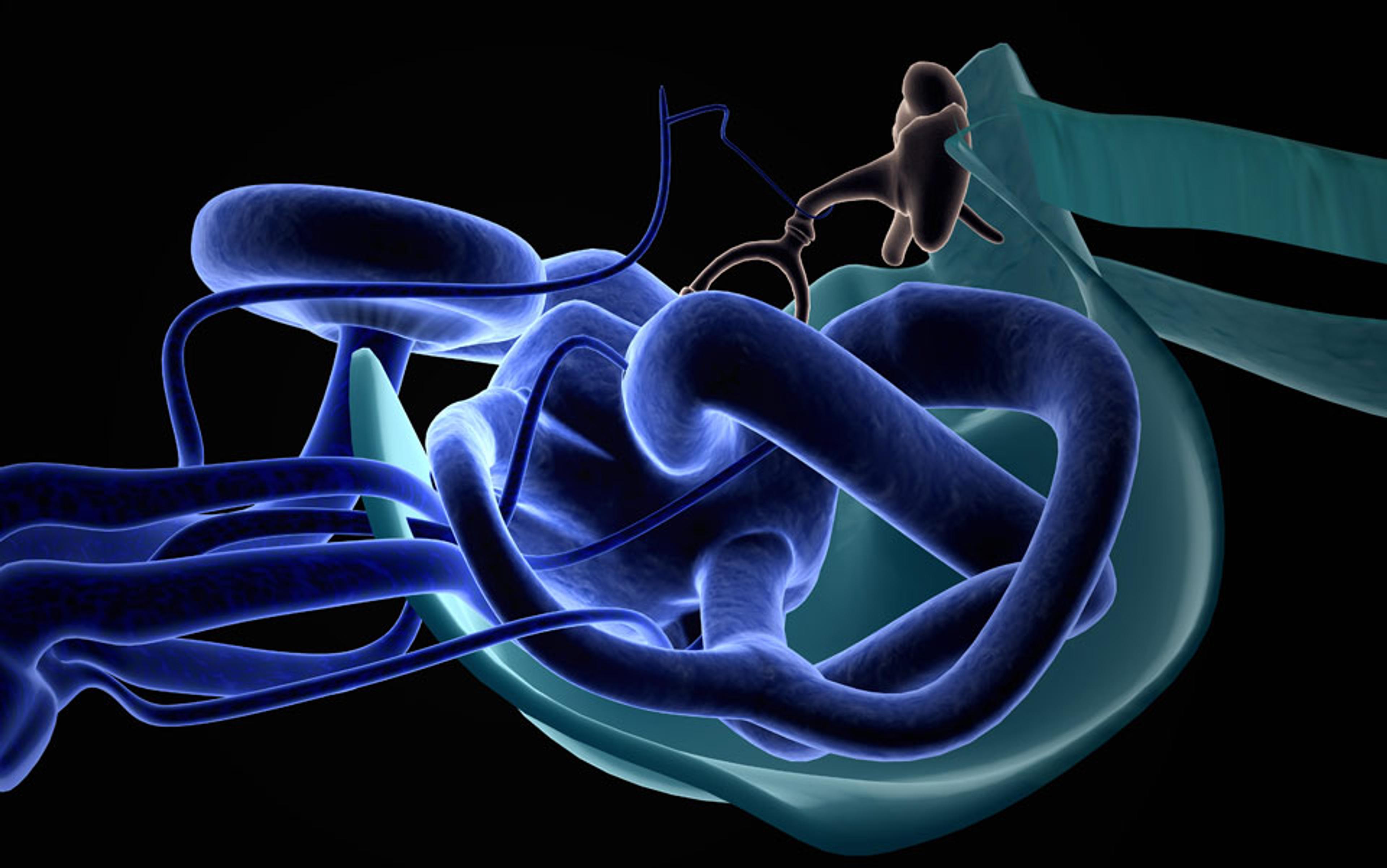

These are dreams of ego and yearning. They often involve actions I once performed unconsciously, when a desire to execute a function was easily and instantaneously transmitted along neural pathways to muscles, ligaments, sinew, and bone, creating movement. Brain. Eyes. Inner ear. In my new world, the keys have been mislaid and I spend my days trying to find them.

The date 15 April 2013 would have been my son Jack’s 19th birthday. He had been dead for 14 months. His three sisters, my husband Tim and I had dinner together, then they went to the cemetery. I didn’t. I sat in my wooden chair, with the carved seat and the woven hickory back, drinking wine. I had thought about Jack every moment of the past year and was exhausted. His death had thrown the family into a well of despair. It was as if we’d all grabbed on to our own ropes and were only now just beginning to haul ourselves out. I drank some more.

When the family returned from the cemetery, I stood up. The room spun violently, causing me to fall back into the chair. Again I tried to stand, but couldn’t. I put my head down and held it in my hands. I can’t move, I told Tim. I could hear myself speaking through my hands but the words didn’t sound right. I began to sweat and felt like I might vomit. Tim brought me a pan, and asked if I wanted help getting upstairs. I mumbled for him to leave me alone.

I spent the night on the rug in front of the cold fireplace, wrapped in a quilt. In the morning Tim said I should go to the doctor’s. But I can’t even lift my head off the floor, I mumbled, and I don’t want an ambulance. Then I asked for the pan and vomited.

Tim went to work. The youngest daughter went to school. I stayed on the floor. If I moved my head up, I was smacked by a violent spinning and I couldn’t open my eyes because the light hurt. When Tim came home he helped me up to bed. With sunglasses on to keep out the light, I lay in the semi-darkness trying to block out the scary thoughts: it’ll never be the same; I’ve had a stroke; I am going blind; I don’t want to think about it. My children were scared but, though I tried to tell them everything would be okay, I didn’t believe it myself.

It was a week before I got to the doctor’s. By that time I could kind of focus my eyes and could walk upright, so long as I didn’t lift or turn my head. Everyone I’d spoken to had some version of the following – oh, their Aunt Mabel had this and went to the chiropractor who did a simple head-turning thing and she was all better. With a tiny bit of digging around on various medical websites, I figured out that they were describing benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), a kind of vertigo that occurs when small crystals in your inner ear are knocked out of place. A certain set of head movements called Epley maneouvres reposition the crystals and, often, you feel instantly better.

But in BPPV, the vertigo is brought on or intensifies when you turn your head in one direction; my vertigo symptoms were constant. It didn’t matter what direction I turned my head: it was all bad. After an MRI scan ruled out a stroke, multiple sclerosis and a brain tumour, my doctor went with a diagnosis of vestibular neuritis. Vestibular (adjective), meaning relating to, or affecting the perception of body position and movement. Neuritis (noun), meaning inflammation of a peripheral nerve or nerves, usually causing pain and loss of function. In short, I was experiencing the physical embodiment of being thrown for a loop.

For several months, I did vestibular rehabilitation therapy, where I spent a lot of time walking down a hallway turning my head side to side, or up and down. I liked to go left, it seemed, which meant that, whenever I tried to walk straight, I’d veer in that direction. Sitting and lying down were fine, but walking was a challenge. I could tell that the neural pathways signaling from my eyes to my brain to my feet were out of whack on the left side. Mark, the physical therapist, told me that a body works very hard to compensate for the loss of any particular neural pathway and that, over time, the right vestibular nerve would figure out how to read the signals that should be travelling up the left nerve. A miraculous theory, I thought, as I lurched down the hallway, hands out to fend off the approaching wall.

Before the vertigo, I had established myself as a travel writer, making up to a dozen trips a year across the United States and abroad. Fleeing home and responsibilities to find meaning in other places and cultures was my drug of choice. The second I got into the car to head for the airport, I looked only forward. After my mother and mother-in-law died, closely followed by Jack’s suicide, everything I had been was called into question: not just travel writer, but daughter, daughter-in-law, mother.

It was a terrible year. Much of the time I felt as if my house was keeping me anchored in despair, that the only moments of peace came on trips to far-flung places where no one knew my back story; I could run away from my sad-sack house and my sad-sack family, and momentarily forget my fury both at my failure and Jack’s betrayal. Tim held the children even closer, terrified he’d lose another one; I fled. I had a hard time letting even my family share my grief.

Vestibular neuritis is a disease of confusion and imprecision that seems to be further exacerbated by anxiety and stress.

I spent 10 days in the Falkland Islands, where I discovered an entire generation trapped in the throes of a kind of collective post-traumatic stress disorder, 30 years after the Falklands War. I recognised the look, the way of storytelling, the desire to talk and to not talk. I felt as if these were my people; they’d gone through a terrifying time and come out the other end, but they would never again be whole. When I returned, I talked so much about the Falkland Islands that my children and Tim grew afraid I was going to move there. I told them I would bring them with me and we could all start over, away from the house (the scene of the crime) and the village my family had lived in for five generations. They didn’t want to leave.

Now I see how I sought out the loneliest places – places where Jack had never been – so there was no chance of running into him in my mind. He would have been out of place, and in my need to order my world – to re-establish a kind of balance that had disappeared with a blast of a shotgun – that could not happen.

The diagnosis of vestibular neuritis is a diagnosis of exclusion. If it’s not this, then it must be that. It affects three or four people out of 100,000, or about 11,000 people a year in the US. Much of the work on trying to understand the disease is being done in Germany. The vestibular rehabilitation therapist said that it could take up to six months for the symptoms to clear up and that after that I’d be fine. His calculation is based on the theory that your undamaged vestibular nerve will fully compensate for the loss of function in the damaged nerve. The health literature about the disease says something different. The recovery rate of peripheral vestibular function is between 40 and 63 per cent, depending on early onset treatment with corticosteroids. I didn’t get corticosteroids, which I guess explains why my peripheral vestibular function on the left seems to be about zero. And for whatever reason, the right vestibular nerve didn’t fully compensate and take up the slack.

Vestibular neuritis is a disease of confusion and imprecision that seems to be further exacerbated by anxiety and stress. You start to wonder if you are in a mental fog and feel unbalanced because of the disease, or if the mental fog and unbalance is caused by the anxiety of worrying that you’ll be in a mental fog and unbalanced. A neat tautology with your health and mental state tightly wound.

It is now almost a year after the initial attack. I’ve been in cognitive therapy and physical therapy, and I underwent a battery of tests at a balance clinic at the University of Rochester in New York. At one point, the technician there tried to fake my inner ear into a state of sickening imbalance by squirting cold, hot, then icy water alternately into each ear. My left vestibular nerve did not respond at all. I left the clinic feeling discouraged and depressed. My sister told me to get used to it; this is now your life, she said. She has multiple sclerosis, so I felt guilty for feeling like I was walking underwater.

the visual chaos of trees and houses and buildings rushing past made me want to vomit, so I’d keep my head down and eyes shut tight

Most of the time I look like I am walking straight but my head tells me something different. The self-consciousness of unsteadiness affects my every move and I often ask my family if I am lurching. Days are planned out in terms of how far I will have to walk. My fear of falling has skyrocketed. This winter, I stayed in the house for days, afraid to venture out in the snow and ice.

Balance comprises three things that have to work together. First, proprioception (from the Latin proprius, meaning ‘one’s own’, individual, and perception) is the sense of the relative position of neighbouring parts of the body and the strength of effort being employed in movement; or, knowing how to get all the parts of your body to move in a co-ordinated way through the world. Location, orientation, then movement. Second, your vestibular system is the sensory system that informs your brain about where you are (in the most elemental and physical sense) and then adjusts for balance and motion. Finally, balance depends upon visual inputs, so if your vision is screwed up, you’re going to have a tough time feeling balanced.

With my initial attack of vertigo, my eyes developed nystagmus, a condition where they rapidly move back and forth (similar to what happens during REM sleep). This weird movement made it difficult to focus on any one thing. I remember looking in the mirror and watching as my eyes shifted back and forth. It was at once disconcerting and embarrassing. I wore dark glasses for weeks because I couldn’t look at anyone without feeling very out-of-sorts: I didn’t know where to look. My eyes also became sensitive to light. Riding in cars, the combination of the nystagmus with the visual chaos of trees and houses and buildings rushing past made me want to vomit, so I’d keep my head down and eyes shut tight.

Now my vision is in flux. Sometimes I need glasses, sometimes I don’t. There are times when I turn my head and see trails, and sometimes images appear segmented, as if I’m looking at an old film slowed to reveal motion frame by frame. My eyes seem to be registering the action just a split second behind what’s taking place. This disconnect often causes me to stumble.

Being out of balance begins to feel permanent.

It’s only when I read research by Dr R Tschan, the lead author of a 2011 article in the Journal of Neurology that followed sufferers of vestibular disease into recovery, that I understand why I feel the way I do. Tschan did an initial study of 59 patients with some kind of vestibular disease, using a series of tests to measure resilience and psychological wellbeing, and a year later he followed up the same patients. Based on their answers to initial questions, he was able to predict which patients would be at risk of developing secondary somatoform dizziness and vertigo (SVD) – ‘an underdiagnosed and handicapping psychosomatic disorder leading to extensive utilisation of healthcare and maladaptive coping’. He points out that few long-term follow-up studies focus on the assessment of risk factors, and concludes that patients should be screened for risk and preventive factors, and offered psychotherapeutic treatment if shown to have insufficient coping capacity to prevent secondary SVD.

Tschan’s study confirms that what I feel is real to me, which in some ways is a relief. But an earlier study on phobic postural vertigo (characterised by dizziness in standing and walking despite normal clinical balance tests) conducted by Johan Holmberg and colleagues at Lund University Hospital in Sweden and published in 2007 in the same journal, also rings true. ‘Patients sometimes exhibit anxiety reactions and avoidance behaviour to specific stimuli,’ the authors wrote. In a year-long study, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, pharmacological treatment and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) were randomly used on two dozen patients, with the finding that CBT had the least significant long-term effect.

It’s clear to me now that no one has the answer. No one knows how to fix something that is literally and figuratively in your head.

People talk about searching for and finding balance in their lives. I want to hit them with my walking stick. Their choices revolve around finding balance between work, family, home, and self. I yearn to have those choices. To me, balance is primal, elemental. I yearn to wake up in the morning and know that this will be the day when I will think clearly and walk confidently; when all the synapses will fire along the right neural pathways; when my anxiety of moving through the world won’t hold me back. I long for the day when I can drive to the airport and board a plane to somewhere new; when I can navigate once more a landscape of foreign hills, desolate plains and wild seashores.

I often catch my daughters and husband watching me. The first vertigo attack terrified them, and the fear told on their faces when they came to the bedroom to offer me food and company. This look eventually got me out of bed. Left to my own devices, I might have wallowed in my new-found misery far longer. Oddly, I think my condition helped us all put our grief in another place. Now there was something else for the family to focus on; my children became adept at reading the cues if I was feeling stressed or anxious, while I came to rely on their judgment. I still haven’t visited the cemetery where my mother and son are buried side by side in the family plot. But I know that when I do, I will be lurching toward the headstones with what is left of my family by my side.