On 2 March 1901, the Buddhists of Rangoon (today’s Yangon) in Burma celebrated the full moon festival, the largest of the year. Visitors, respectfully barefoot, filled the grounds of the huge gold-plated Shwedagon Pagoda, the country’s most important Buddhist pilgrimage site, its glimmering spire visible from miles away. On the platform, people were chanting, meditating, offering candles, flowers and water, talking. The surrounding streets were alive with food stalls, music and drama performances, banners and decorations. In the midst of these crowds and celebrations, an act of profound civil disobedience took place: a shaven-headed Buddhist monk stepped out in front of an off-duty colonial policeman, in the employ of the British Empire, and ordered him to take off his shoes.

We can imagine the ripple that spread as people noticed the confrontation. Wrapped in the saffron robes of religion, the monk was not just challenging one policeman. His protest targeted the power of the empire, the largest the world had ever seen.

News of this act spread from the Rangoon bazaars into the Burmese newspapers. It sparked attempts by the colonial authorities to control the situation, followed by further polemics and confrontations, and launched the ‘shoe issue’ as a rallying-point for Burmese anticolonialism for the next two decades. When Barack Obama visited the Shwedagon more than a century later, he did so barefoot.

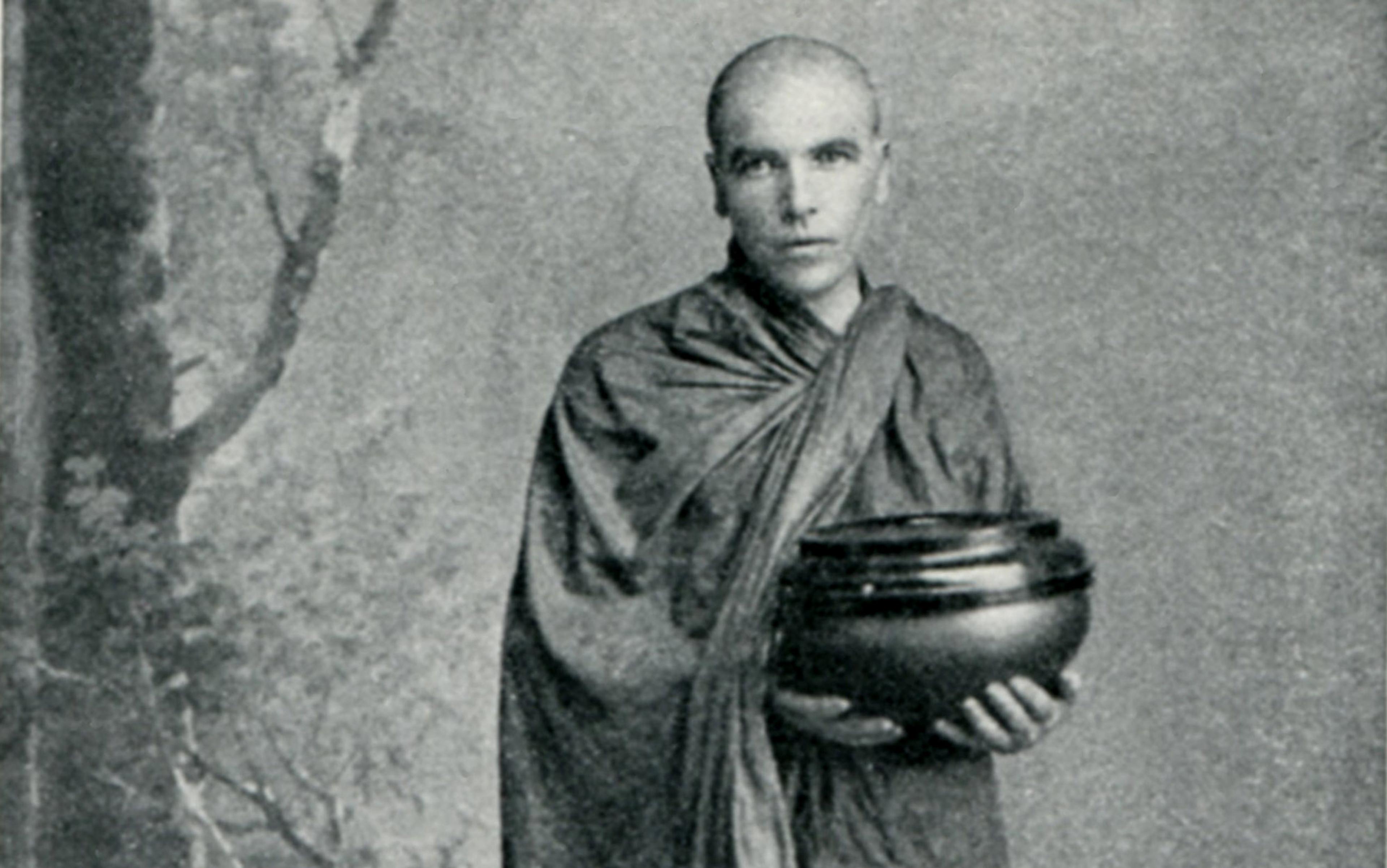

Who was the monk that started it all? The eyes that stared down the policeman were the blue eyes of the mysterious ‘Irish Buddhist’ from Rangoon’s Tavoy monastery, known to many by his Buddhist name of U Dhammaloka. What was his original name? Where had he come from? And what was an Irish-born man doing as a Buddhist monk, in Rangoon, challenging imperial power beneath a full moon?

Even in his own day, Dhammaloka was no easy man to pin down, despite the best efforts of the colonial police and intelligence services. He used at least five aliases and left out about 25 years of his past in the very different tales he told. It took me and my co-authors Alicia Turner and Brian Bocking a decade to put together the pieces in our book The Irish Buddhist (2020) – but, in tracing his life, we rediscovered an extraordinary biography that offers a window on the crowds, networks and social movements that brought about the end of empire in Asia.

Burma had been conquered by Britain in three wars, the final one followed by a brutal counterinsurgency in the late 1880s, a little more than a decade before the confrontation in Rangoon, the colonial capital and port city from where Burma’s wealth was shipped overseas. Since the Indian uprising of 1857-59, European colonisers in Asia were uncomfortably conscious of just how few they were. In colonised Burma, as elsewhere, great efforts went into intensifying racial hierarchies, marking off the small numbers of whites and their colonial officials from the millions of ‘others’ they ruled over: Burman Buddhists, Indian Muslim dockworkers, the Chinese diaspora, Tavoy sailors, Shan and other ethnic minorities. Empire was not just military power and economic exploitation. It was also, crucially, cultural hierarchy.

Scene upon the Terrace of the Great Dagon Pagoda. Watercolor by Lieutenant Joseph Moore, British Army from a series depicting the First Anglo-Burmese war (1824-26). Courtesy the Library of Congress.

Clothing – especially shoes – was key to the imperial colour line. In Burma, like much of Asia, shoes are considered dirty. They are not worn inside houses, let alone in sacred spaces, as a sign of basic respect. For whites and representatives of the Empire, like the off-duty policeman, to take off one’s shoes would have meant lowering oneself to the level of the barefoot or sandal-wearing masses: not just personally humiliating but dangerous to imperial power, which depended on constantly reinforcing racial, cultural and institutional hierarchies. When poor whites ‘went native’ – settling down with local partners, taking casual labour alongside Asians, wearing the same clothes as their neighbours and coworkers – it marked a dangerous breach in white solidarity.

A European Buddhist – someone who went as far as converting to a local religion, bowing down to ‘heathen idols’, perhaps a monk or nun ritually subordinated to an Asian religious hierarchy, begging for food and of course barefoot, shaven-headed and wearing robes – epitomised this breakdown of racial hierarchies. Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim (1901), which tells the story of the orphaned son of an Irish soldier, brought up in a Lahore bazaar and following a Tibetan Buddhist guru, was a bestseller that helped win its author the Nobel Prize.

Did the empire actually respect Burmese religious sensitivities, in their own holy places – or not?

Empire and religion were deeply intertwined: ‘bringing the Gospel to the heathen’ was a key justification of colonialism (alongside claims familiar today: bringing modern science and education, rescuing women, or bringing rational government). The imperial establishment belonged to approved Christian denominations, and in 1901 the missionary effort was close to its height, supplementing the brute force of military power and colonial law with the soft power of conversion and Christian schools (run in English and supported by the state).

Yet this brought risks for a colonial power that had to proclaim itself officially neutral around religion, willing to rule Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Christians and others without fear or favour. By highlighting shoes in pagodas, Dhammaloka put his finger on this contradiction. Did the empire actually respect Burmese religious sensitivities, in their own holy places – or not? Either answer was risky for the structures of imperial and racial power.

This weak point had long been probed in colonised Ireland, where the Emancipation movement had asserted the rights of the Catholic Irish against the Protestant establishment to great effect in the 1820s, enabling national self-assertion and political organising under the protection of local religion, which British colonial authorities could not be seen to attack directly. Later in the century, mass participation in the Land War ended the (largely Protestant) aristocracy, and saw their (mostly Catholic) tenants coming to own the land they worked, while the ‘Irish Party’ became increasingly significant in Westminster.

At the same time, the Irish were leaving the island. Of the 8 million before the catastrophic 1845-49 famine, a million died and another million emigrated in the following decade; emigration eventually brought the population down to just over 4 million, as the young left for the factories of Boston or Birmingham, for Australia or Canada. One of these was the boy who would become ‘U Dhammaloka’.

But who was he? The answer is not easy to untangle. History, of course, is written by the winners – and the colonial newspapers that are the most common sources for his life were written for and by people who had committed themselves to colonialism, becoming colonial officials, soldiers, missionaries and others, and moving to Asia to become part of the imperial structure. Dhammaloka was also a working-class radical who sailed very close to the wind. His multiple aliases and missing years are common in a time where mugshots and fingerprints were widespread as tools for state surveillance of the migrant poor; covering his tracks whenever possible was sensible behaviour. We can trace his life only thanks to the huge strides made in digitising newspapers, books and archives in recent years. It turns out that his story crosses at least 12 different countries.

Despite his aliases, the name ‘Laurence Carroll’ fits with a birth in 1856 in the shadow of the church at Booterstown, a village becoming a suburb, an hour’s walk south from the Dublin docks (his name was also confirmed by an Irish journalist in Singapore). Carroll was the youngest of six. He left school around 13 and emigrated to Liverpool. Finding work in a ship’s pantry, he is recorded as arriving in New York in 1872. He worked on cargo ships up and down the East Coast before becoming a ‘hobo’ (a migrant worker) and travelling west, jumping trains and making his way via Chicago and Montana to the fruit boats of the Sacramento River and eventually the San Francisco docks.

Dhammaloka’s anti-racism was probably chosen on this long journey. Liverpool docks were contested between English and Irish workers. New York and the hobo trails, following the US Civil War, saw many Irish ‘becoming white’, using ethnic solidarity and racism to cement their position at the expense of Black people. He passed through Montana in the period between Red Cloud’s War and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Northern California – and the San Francisco docks – were sites of anti-Chinese racism but, throughout his later life, we see a refusal of racism and a consistent choice of cross-racial solidarity many years in the making.

Somewhere along the way, he also picked up the skills and ideas of late-19th-century radicalism, which he would put to good use in Asia alongside local and Irish traditions. This may explain the gaps in his biography – these were the years of Fenian (Irish republican) violence, of the Molly Maguires, a secret labour society that fought Pinkertons in the Pennsylvania coalfields, of the 1877 general strike, and of a widespread radical culture, not least among migrant workers.

He became an anticolonial celebrity: crowds of thousands would travel, sometimes for days, to hear him speak

From San Francisco, Carroll worked the trans-Pacific ships to Yokohama, and eventually became a docker in Rangoon. In 1900, he ordained as a Buddhist monk in a major ritual celebrated by senior monks, with another 100 monks and 200 laypeople in attendance, all sponsored by a Chinese Buddhist. Working in the multi-ethnic spaces of sailing and dock work, Dhammaloka claimed to speak seven Asian languages. At the very least, he certainly spoke Hindi-Urdu well enough to win arguments.

More than this, he knew how to get on with people. Like many a sailor, hobo and Irish emigrant, telling stories helped him make new friends and get through hard times. Living on his wits, he was quick to make a connection, interested in other people’s lives and worlds, and outraged by the injustices they suffered. When people met him, they remembered him – and told Dhammaloka stories long after he had passed through their lives.

In particular, Dhammaloka loved the richness of Asian cultures and sought to defend them against colonial destruction. In his 14 years as a campaigning monk, he was active in the countries we now call Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh, Burma, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Japan, Australia, and perhaps also China, Nepal and Cambodia. Along the way, he gradually became an anticolonial celebrity: crowds of thousands would travel, sometimes for days, to hear him speak in remote places in rural Burma or Sri Lanka, so much so that laws may have been changed to stop him. His pamphlets were published by the tens or hundreds of thousands, and distributed widely.

He became immensely popular for his willingness to confront colonial injustices, such as the kidnapping for slave labour of young boys and women, or corruption in high places. Colonial officials regularly abandoned their ‘native wives’ and children when they retired ‘home’ to England: Dhammaloka campaigned against this so effectively that the viceroy forced them to legalise such marriages, hence preventing them from remarrying ‘at home’.

But he was not just an isolated troublemaker. At every stage he acted as the dramatic ‘front man’ for effective Asian networks of many different kinds: Sri Lankan anticolonial Buddhists, Indian radical activists, the diaspora of the Tavoy (Dawei) ethnic minority across Burma and Thailand, the Chinese diaspora in Burma and in Singapore, a Shan chieftain from Burma’s borders, Japanese Buddhist modernisers – and beyond these, the developing social movements of pan-Asian Buddhist revival and popular self-organising that would eventually help sweep the empire away.

Buddhism played a crucial role here, connecting people across Asia in very different ways than did European empires. The religion had been born in India and Nepal, then spread into today’s Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan and along the Silk Road. It was dominant in British Burma and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and French-ruled Indochina (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). It played an important role in today’s Malaysia, Singapore, China and, to some extent, Korea.

Of the three Asian countries uncolonised in 1901, Siam (today’s Thailand) and Tibet were Buddhist. The rising power, Japan, shortly to be the first Asian country to defeat a European power in the Russo-Japanese War, counted Buddhism among its main religions, and sent Buddhist clergy to the rest of Buddhist Asia and to the diaspora in Hawaii, California and Brazil. Buddhism was older than Christianity and (wrongly) believed to have more adherents. Together with the empire’s weak spot around religion, this gave Buddhism real potential as a vehicle for anticolonial action.

As Dhammaloka said – repeatedly, loudly and publicly – colonialism came with ‘the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun’. From this perspective, a practical programme of challenging missionaries and working for temperance followed. The Gatling gun – military conquest – could not be challenged directly; but the Irish move of challenging colonial religion as a proxy for imperial power worked well.

More than this, an Irish Buddhist was a worry for the British Empire, and not only in Kipling. Irish emigrants worked not only in factories or as domestic servants. Some, like Dhammaloka, did work on the ships and docks that held the empire together. Many of the poorest joined the British Army: the rifles pointed at Asian crowds were often held in Irish hands. But what if they lost their loyalty to the empire, and made common cause with Burmese – or Indian, or Sri Lankan – people who were also organising themselves and might once again revolt against foreign rule? And what if they converted to a pan-Asian religion like Buddhism? When Dhammaloka confronted the off-duty policeman at the full moon festival in 1901, these were some of the unnerving questions that he brought to the fore.

Missionary critique of Buddhism was legitimate, but a monk’s critique of Christianity was sedition

In the decade that followed, he was active across Asia on speaking tours, founding schools, creating organisations, publishing and distributing tracts. The year 1909 saw a high-profile tour of Ceylon marked by newspaper polemics, counter-lectures, police surveillance, threats of legal action, disrupted meetings – and very large crowds. In a time of increasing tension across the empire – with Gandhi’s boycott movement taking off in India and facing severe repression – colonial authorities may have felt they had to intervene.

The east corner of the Shwe-Dagon Pagoda, Rangoon in 1907. Photograph by Philip Adolphe Klier. Courtesy the National Archives UK.

In late 1910, Dhammaloka was charged with sedition in the Burmese town of Moulmein, centred around his challenge to ‘the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun’. Complaints about this had been made by two missionaries: one Anglican and the other Baptist (the latter shortly to be fined for his mistreatment of inmates in the institute for the blind). The streets were so full of Dhammaloka’s supporters that his trial was postponed. Eventually, it was held surrounded by soldiers and police. He was convicted: missionary critique of Buddhism was legitimate, but a monk’s critique of Christianity was sedition.

On Friday 13 January 1911, the streets of Rangoon, too, were filled with a multi-ethnic crowd supporting Dhammaloka in his appeal against the Moulmein conviction. He was pulled in ceremonial procession by a crowd of laity and Buddhist monks, an honour normally reserved for the most senior monks and members of the deposed royal family. It was not only the ‘Burmese bazaar’ that closed that day. Dhammaloka’s Tavoy monastery – a node for that ethnic diaspora and for poor whites like him – was located in Chinatown, where he had many supporters. The Chinese and Indian bazaars also emptied on to the streets of Rangoon, and even the local cinema (the first in the country) donated two days’ takings to the defence fund.

His lawyer was U Chit Hlaing, later a leading nationalist figure, but Dhammaloka’s most strategic supporter was Pranjivan Mehta, a Mumbai-born physician and close ally of Gandhi’s. The newspaper Mehta founded, United Burma, was seen as deeply subversive by the authorities, but even more threatening was his developing alliance with the Indian Muslim dockworkers who made Rangoon’s activities as a colonial port possible. This multi-ethnic and multi-religious crowd – Burmese, Indian and Chinese – stood behind Dhammaloka in his confrontation with the British Empire, and prefigured the alliances across entrenched ethnic and religious divides that challenge the Burmese military dictatorship today.

Faced with this incipient alliance, the authorities tried to lower the stakes without losing face. Dhammaloka was bound over to keep the peace: forced to stay within the law for 12 months on pain of his supporters losing the bond money they had to put up for him. (We discovered some of these details in the Swedish-language pages of the Minnesota Forskaren, an anarchist newspaper that republished clippings Dhammaloka had sent to his radical free-thinking allies in the New York journal The Truth Seeker.)

Then, despite the multi-ethnic struggle he had instigated and his growing prestige, the day after his term of good behaviour ended, Dhammaloka sailed for Australia, never to return to Burma. From Melbourne came a pseudonymous letter announcing his death, signed with the surname of an Irish labour organiser, and obituaries were published around the world. A few months later, he reappeared in Singapore, Penang, Ipoh and Bangkok, and claimed to have spent time in Cambodia. He vanished for good in late 1913 or early 1914.

Despite our best efforts and those of collaborators around the world, we have not been able to find out what happened to Dhammaloka. Perhaps he died quietly, somewhere remote, with the impending world war drowning out the news. Maybe he was killed and buried somewhere unknown. Or perhaps he changed his name and costume again, slipping away to lead another life somewhere else. We do not know.

What we do know is that his story gives us an unexpected window into the multi-ethnic grassroots that in these decades transformed anticolonial resistance from a largely elite activity, led by Western-educated middle-class activists, to the mass popular struggles that would eventually lead to the end of empire.

Then, as now, 60 per cent of our species lives in Asia. Asian decolonisation alone is the single largest social change that movements from below have brought about in the past 100 years – making it an important touchstone for today, when the question of whether climate justice struggles can overturn the fossil fuel capitalism driving us headlong to climate breakdown is an existential issue across the planet. Or, indeed, in an age when the question of what decolonisation might look like today, after national independence has failed to resolve those problems, and the effects of empire and slavery live on, is a burning issue across the world.

It was far clearer that empire could and should be ended than what would come next

The visions of the future that Dhammaloka and others in his generation had were naturally shaped by their present. In multi-ethnic, multilingual empires held together by telegraphs, railways and steamships, today’s world of independent nation-states, each defined around a single dominant ethnicity, was not obviously the wave of the future – indeed, nostalgia for past local kingdoms and empires was still widespread. The vision of a pan-Asian Buddhism did not come to pass (although we are familiar with pan-Islamisms of various kinds). Liberals foresaw a world shaped by modern science, education and rationality. Communists and anarchists had their own internationalist visions of the future.

In the 1910s, it was far clearer that empire could and should be ended than what would come next. This would only really come into focus in the decades that followed, as the struggles of peasants, urban workers, women, religious groups, ethnic minorities and others were brought under the leadership of nationally organised elites-in-waiting that attempted to make a state in their own image. Yet the struggles of that earlier generation laid the groundwork for what came afterwards. What we do, in our attempts to bring about a better world, is more foreseeable than the details of the visions that we imagine, of a future that even in a much smaller world defied the brightest minds of Asia to conceptualise. It is not by writing blueprints but in the concerted efforts to challenge the forces of destruction that things change. This thought can, perhaps, help us relax some of our attempts to map out the future, and encourage us to pay more attention to how we work together today to overcome the current cycle of catastrophe.

We can also see that Asian (and African) decolonisation was not a single homogenous thing. The different forces that predominated in different countries meant that China and India, Burma and Vietnam, Tanzania and South Africa inhabited this new shape of independent nation-states in very different ways. So, too, we can imagine that within broad parameters there may well be many different kinds of ecologically sustainable futures possible.

From my own work on the life of U Dhammaloka, I have drawn a deep respect for Burma’s Civil Disobedience Movement today and its capacity to challenge anti-Muslim and anti-Rohingya racism in the Burman Buddhist majority, as well as to connect many different social classes and ethnicities in a shared challenge to the dictatorship. The forces ranged against them are massive and brutal; each day brings news of more disappearances and killings. And yet they do not give up, any more than we should when faced with climate despair or the repression of ecological activism. After all, they have been here before: in previous uprisings that have caused military power to wobble, in the end of British rule in Burma, and before, on the streets of Rangoon, 100 years ago, with this irrepressible, quirky, brave and remarkable Irish Buddhist.