Listen to this essay

29 minute listen

I look at my Fitbit and note despondently that I have done only 2,247 steps today. I haven’t met my ‘hydration goal’ or crossed everything off my to-do list. I didn’t think of three things I was grateful for before I went to sleep last night, nor did I meditate this morning. I didn’t wake up early enough, and I probably won’t get seven to nine hours of sleep. The perfect version of myself hovers in my peripheral vision – healthy, happy and, above all, productive.

We live in an age of self-quantification and the glorification of productivity. Bullet journals, habit trackers, smart watches – all of these tools allow us to collect data about ourselves in a frenzy of self-improvement. My Instagram feed is flooded with videos of thin women with smooth shiny foreheads and gleaming white teeth, extolling the virtues of 5 am workouts, lengthy skincare rituals, and gratitude journals. We seek out ‘hacks’ that will enable us to be ever-more efficient, and to extract the most value possible from our time and possessions.

This all feels very modern, and – we might sensibly assume – inextricably linked to the death throes of late capitalism, where time is money and consumption is king. Yet this culture of self-quantification in the pursuit of self-improvement long predates social media, algorithms and targeted advertising. In fact, we can trace its roots back into the daily lives and preoccupations of the Victorian middle classes.

‘The world is too much with us,’ complained William Wordsworth in 1807. Almost 30 years later, Alfred, Lord Tennyson struck a more triumphant note:

Not in vain the distance beacons. Forward, forward let us range,

Let the great world spin for ever down the ringing grooves of change.

The Victorian era was an epoch defined above all by an obsession with progress. The Victorians were great innovators, and they were also utopians, envisioning a perpetual process of improvement: not only of the self, but of society, of all mankind. Royal commissioners and philanthropists descended in droves upon the slums of London to investigate poverty and sanitary conditions. Wealthy industrialists funded libraries, town halls, public works and sewers. Prince Albert wrote reports on housing. The middle classes enthusiastically consumed scientific knowledge circulated in periodicals and treatises in the pursuit of ‘rational amusement’. The totalising representation – the text or image that would reveal all – was an implicit goal of Victorian culture, from Wordsworth and Charles Dickens to the panorama and the camera. There was a frenzy of measurement and map-making. Data would lead to understanding, and understanding would enable mastery.

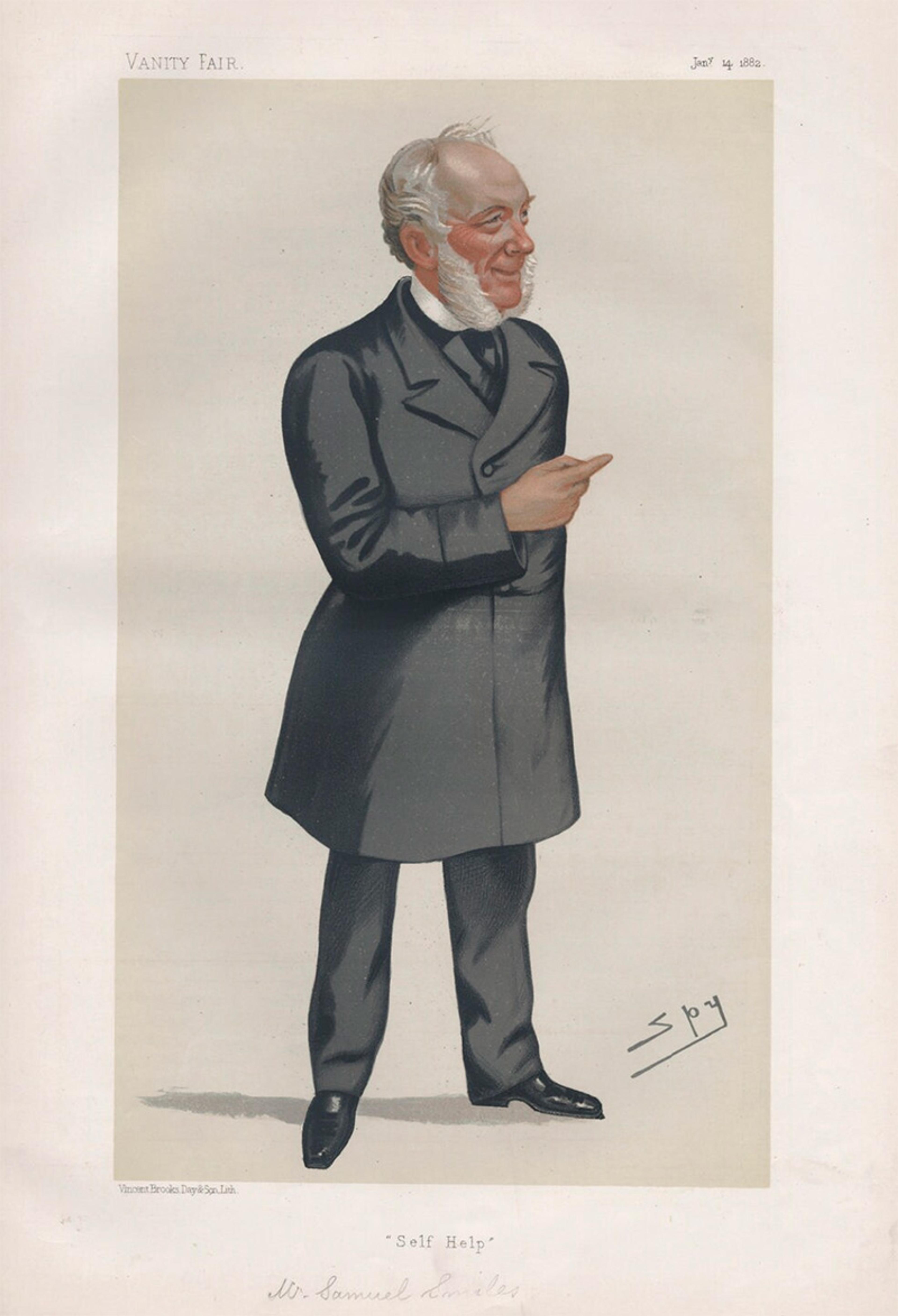

Samuel Smiles by Leslie Ward (‘Spy’), published in Vanity Fair in 1882. Courtesy the NPG London

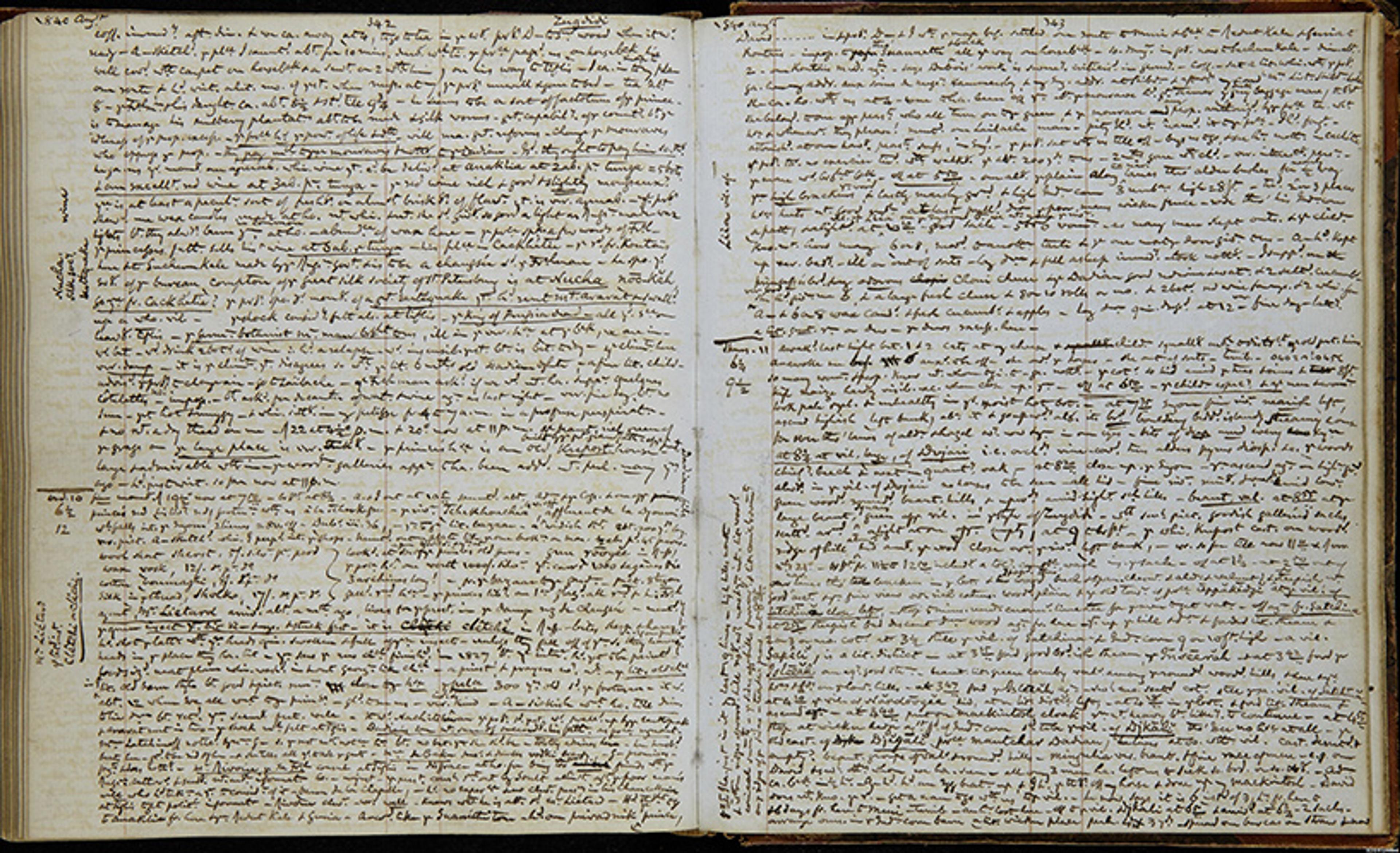

The 19th-century obsession with self-improvement and self-discipline is perhaps best exemplified by Samuel Smiles’s book Self-Help; with Illustrations of Character and Conduct (1859), which championed hard work, good habits and perseverance. It sold 20,000 copies in the first year of publication. Above all, the key was to be active in the pursuit of progress: the greatest Victorian sin was idleness. As the 15-year-old Victoria, heir presumptive to the throne, virtuously wrote in her diary on the 27 January 1835: ‘I love to be employed; I hate to be idle.’ Just as they sought to measure and quantify the progress of Western civilisation, so the Victorians sought to measure progress and improve the self through the simple practice of keeping a diary.

A printed diary held out the promise of total control over time, place and the self

Indeed, the great Victorian innovation in diary-keeping was the switch from the use of the diary solely as a means of reflecting on past actions to the use of pre-printed diaries to plan the future. Diaries were no longer just a record of experience; they were an organisational tool. A mania for progress, industry and commerce had seized the nation, trade was flourishing in the bustling capital, and these new times generated new commodities. Tasks, appointments, memoranda – all could be jotted down in a neatly structured pocket diary that would help you use your time as productively as possible.

Industrialisation, imperialism and rising bureaucracy fuelled demand for desk and pocket diaries to record meetings, appointments and financial transactions. Printed diaries with dated pages became a popular stationery product, with an unprecedented variety and number of these commercial diaries sold to purchasers who sought to organise their lives in the pursuit of productivity. Alongside pages for the writer’s notes and accounts, the diaries included pages of printed information: train timetables, tide times, public holidays, weights and measures, etc. In this way, the new printed diary drew on the tradition of the long-established family almanac, combining the functions of almanac, calendar and diary in one multifunctional book.

Early diaries sold by John Letts in London. Courtesy and © LettsGroup 2025

A printed diary held out the promise of total control over time, place and the self. In 1812, the stationer John Letts began selling a yearly printed diary at his shop in the Royal Exchange in London. The diary was a huge success, and by 1862 Letts offered 55 different versions targeted at specific social groups, with prices ranging from sixpence to 14 shillings (or £1.50 to £42 in today’s money). By 1900, Letts was selling almost a quarter of a million diaries a year, and the printed diary was established as an essential feature of commercial life. No longer merely a space to reflect on what had been achieved, the diary was also a place to plan what was yet to be accomplished.

Then, as now, the writing of a diary required time, light, materials and literacy. Studies of surviving British diaries show that, prior to the 19th century, the majority of diaries were written either by people conscious of their own importance and the value of their recorded experiences – such as aristocrats, members of the court and famous authors – or by fervent Puritans anxiously seeking signs of their own salvation. The first published guidebook for diary-keeping was by the Puritan minister John Beadle, The Journal or Diary of a Thankful Christian (1656), which insisted on the need for Christians to give a ‘strict account’ each day ‘of all our ways, and of all [the Lord’s] ways towards us’. This practice of daily self-examination profoundly shaped the diary genre as it developed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, emphasising the need to account for one’s thoughts and actions before God in the pursuit of salvation. So the diary was not a Victorian innovation, but it was during the 19th century that diary-keeping really took off, as printed diaries began to be mass-produced and sold to the rapidly expanding class of white-collar workers in Britain’s thriving towns and cities.

The 19th century also saw the emergence of a popular canon of published diaries, such as those of the writers John Evelyn (1620-1706) and Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), published in 1818 and 1825 respectively. Such diaries were widely read, sparking a new literary vogue, appearing as plot points in novels and plays, as well as being quoted at length in biographies. Pepys’s diary went through seven editions in the 19th century, and when Queen Victoria published her Leaves from a Journal of Our Life in the Highlands (1868), more than 100,000 copies were sold in the first year alone. The cultural historian Peter Gay in The Bourgeois Experience (1993) has thus described the Victorian era as the ‘golden age’ of diary-keeping, while the literary scholar Rebecca Steinitz states in Time, Space, and Gender in the 19th-Century Diary (2011) that the diary was ‘ubiquitous’ in 19th-century Britain, the form being a ‘uniquely effective vehicle for the dominant discourses of the century’.

These diaries were often perfunctory and functional: the clothes they wore, the food they ate, gossip and arguments

Within the diary, Enlightenment ideals of scientific empiricism could be harnessed in support of the evangelically inspired project of self-improvement. Increasing literacy rates, cheaper materials and new printing technologies encouraged the production and consumption of diaries on an unprecedented scale. The brothers George and Weedon Grossmith’s satire The Diary of a Nobody, first serialised in Punch in 1888 and published as a comic novel in 1892, describes the daily life of the ‘nobody’ Charles Pooter, a clerk who lives in the London suburb of Holloway with his wife Carrie. In the introduction Pooter asks:

Why should I not publish my diary? I have often seen reminiscences of people I have never even heard of, and I fail to see – because I do not happen to be a ‘Somebody’ – why my diary should not be interesting. My only regret is that I did not commence it when I was a youth.

This parody reflects just how widespread the habits of reading published diaries and diary-keeping had become by the turn of the century among the lower-middle classes, those Mr and Mrs Pooters living unremarkable lives in leafy suburbs.

These texts were often perfunctory and functional. Diarists recorded their physical health, their relationships with family and friends, their finances, their attendance at church, the books they read, their letters and appointments, the clothes they wore, the food they ate, gossip and arguments. For example, the diaries of William Gladstone run to 41 volumes, the great statesman having made almost daily entries between July 1825 and December 1896. Yet the majority of these entries are brief lists of persons written to and seen, places visited, meetings attended, and books read. He sometimes added a sentence or two of commentary, and only very rarely did he include an extended passage of soul-searching and reflection. While scholars of the 19th century have inevitably been attracted to diaries that contain lengthy passages of introspection, ripe as they are for literary analysis, most surviving Victorian diaries are similarly characterised by brief, banal entries about practical, quotidian concerns.

The literary scholar Anne-Marie Millim in 2013 describes the 19th-century diary as a ‘monitoring tool’ in which the ultimate goal was self-mastery. By carefully recording their successes and lapses, diary-writers could compare the achievements of their past, current and future selves. For example, in 1852 the 17-year-old public schoolboy Robert Nunns used his sixpenny pocket diary to chart his social, physical and academic progress. The second son of a reverend, Nunns grew up in Leeds and attended Marlborough College between 1848-54. He diligently recorded his weekly ranking in the 5th form, as well as his attendance (or absence) from church, his leisure activities, and even his weight (7 stone 9 lbs on Thursday 12 February). He often compared himself with his elder brother Thomas, two years his senior, as well as his classmates. On Friday 2 January, he confessed he ‘did not do any holiday task yesterday’, and on Monday 5 January, he glumly noted: ‘Wood has done his.’ On 21 January, he excitedly recorded a great victory over his elder brother: ‘I checkmated Tom at Chess!!’ Back at Marlborough, on Sunday 7 March, he noted in his weekly update of his form ranking that ‘Benthall above me by one mark’, which is followed on Saturday 17April with the gleeful statement: ‘Benthall got a 0 !!!’ Here we see the use of the diary to measure Nunns against his peers, as well as to chart his academic progress, and a competitive mindset that matched the spirit of the age.

After leaving Marlborough, Nunns studied at Cambridge before following his father into the Church, taking Holy Orders in 1858. He married in 1865, was rector and vicar of various parishes in West Sussex and Suffolk during his ecclesiastical career and was survived by seven children when he died in 1906. The diary allows us to cut through this rather staid and conventional biography of a respectable Victorian clergyman, offering a tantalising glimpse into the mind of a teenage boy on the cusp of manhood.

Diary-keeping was a convention of middle-class child-rearing, with parents such as Charles Darwin and his wife Emma using diaries to anxiously record the physical, intellectual and religious development of their children in accordance with the Romantic notion that ‘the child is the father of the man’. Blank or pre-printed diaries were also a common domestic gift, as parents gave diaries to their children and children gave diaries to their servants. In Between Women (2007), the literary scholar Sharon Marcus writes that Princess Victoria was instructed in how to keep a daily journal by her beloved governess, Lehzen, and until Victoria became Queen, her mother inspected her diaries daily.

Gladstone recorded each whipping episode with the Greek letter Lambda (λ)

In fact, the practice of reading the diaries of friends and relatives was widespread, meaning that diaries were texts on the threshold of public and private. Shared reading of diaries was a common habit within marriages. A private diary was not necessarily a secret text. As Marcus states: ‘Far from being a repository of the most secret self, the diary was seen as a didactic legacy, one of the links in a family history’s chain.’ Diarists wrote for prospective readers, addressing journal entries to their children, writing annual summaries, or rereading and annotating diaries in old age. Diaries were often bequeathed to family members as part of a personal archive or used to assist with the writing of an autobiography or posthumous biography. Yet Nunns described with apparent horror an incident in which one boy found the diary of another and ‘read it through’, indicating that such an act represented a clear violation of privacy. It was for the diarists themselves to determine the audience of the private text by policing access to the manuscript. Then, as now, reading someone’s diary was a deeply intimate act.

Indeed, the use of secret code by some diarists to record particularly sensitive information in itself anticipates an audience for the un-coded content. When Gladstone began to self-flagellate to manage his feelings of sexual arousal after looking at pornography and doing ‘rescue work’ with prostitutes in London, he recorded each whipping episode with the Greek letter Lambda (λ). On 13 July 1851, he recorded:

Went with a note to E[lizabeth] C[ollins]’s — received (unexpectedly) & remained 2 hours: a strange and humbling scene — returned & [Lambda]

Elizabeth Collins was a prostitute whom Gladstone described in Italian as ‘beautiful beyond measure’ in another entry, in 1852. The use of Italian rather than English indicates his self-consciousness about the impropriety of such praise of ‘fallen women’. From 1850, he met prostitutes regularly in London, and their individual names frequently appear in his diary.

Anne Lister, attributed to Mrs Turner of Halifax, 1822. Courtesy Wikipedia

The diarist Anne Lister of Shibden Hall (1791-1840), the daughter of a Yorkshire landowner, and an active lesbian, began to keep a diary when she was 15, using code to record her sexual feelings and relationships as well as her financial insecurity. Her diaries, which comprise 26 bound volumes from 1816-40 as well as loose pages from 1806-10, are three times the length of Pepys’s famous diary. About 15 per cent is written in code. The symbol X was used to indicate masturbation and/or orgasm, while a ‘kiss’ symbol of a Q with a curl was used to mark a sexual encounter.

Lister’s diary code. Courtesy West Yorkshire Archive Service

The code had been originally devised with her school friend Eliza Raine, who called Anne her ‘husband’ in writings that use the same code, and Anne went on to share the code with several other lovers, thus regulating and privileging access to the most private sections of the text. When her descendant John Lister first discovered the diaries and cracked the code in the 1880s, he promptly hid the diaries behind wooden panels in the walls of Shibden Hall; they were made available to the public only in the 1980s. Nunns similarly used a pictorial code to record visits to pubs such as The Bell and The Fighting Cocks during his terms at Marlborough, indicating that this was particularly sensitive information.

Lister’s last known diary entries, from 9-11 August 1840. Courtesy West Yorkshire Archives Service

The French literary theorist Philippe Lejeune suggests in On Diary (2009) that we should understand the diary not as a consecutive narrative but as a system of daily habits, a modus operandi, a way of being, as much as a record of being. The diary was not a coherent narrative of the self so much as the record of the self as a work in progress, and the diary was promoted as a habit that would encourage the formation of ‘character’, a virtue that was increasingly understood as the product of an accumulation of good habits, as opposed to an innate quality. The pamphlet ‘Rules for the Behaviour of Children’ (1840), published in Birmingham, included, among its religious exhortations, the instruction ‘Be diligent in business. Reason. Because with the blessing of the Lord, it ensures success.’ The emphasis on ‘diligence’ highlights the significance of good habits and fortitude as preparation for the ‘struggle’ of the commercial world of Birmingham, a fast-growing English industrial town, and the way in which poverty was interpreted as the outward sign of moral failure. The diary functioned as both a practical and an emotional response to a rapidly changing society, reflecting a desire for control and stability. The intellectual historian Stefan Collini links the intensified awareness of the role of habit in informing ‘character’ to a distinctive preoccupation with ‘the shaping power of time’, as reflected in contemporary enthusiasm for the study of slow processes of development such as geological layers.

In the Victorian period, people were more aware of the passing of time than ever before. Wrist watches and clocks allowed the middle classes to schedule their days with precision. Trains and train timetables, telegraph wires and the penny post shrank distances and accelerated the pace of life. In 1880, the Definition of Time Act proclaimed a standardised national time: Greenwich Mean Time. Diarists assiduously noted the timings of their days. Nunns recorded with pride when he rose early, and noted the days when he went to bed late, reproducing social norms that emphasised ‘good habits’ and strict routines. For example, in the same entry in which Queen Victoria proclaimed her love of industry and loathing of idleness, she gave a precise schedule of her day:

I awoke at ½ past 7 and got up at a ¼ past 8. At ½ past 9 we breakfasted. At 1 we lunched … At ½ past 1 came Baroness Howe and Sir Wathen Waller. At a ¼ past 2 we went out walking … till a ¼ to 3. At a ¼ to 6 I played with Mamma till a ¼ past 6 … At 7 we dined. I stayed up till a ¼ to 9.

The cultural historian John Gillis states that ‘No well-managed household could afford to be without a full complement of clocks and calendars carefully synchronised to the beat of the new industrial and political order.’ In his influential article ‘Life at High Pressure’ (1875), the Liberal writer W R Greg claimed that ‘the most salient characteristic of life in the latter portion of the 19th century is its SPEED.’ Such anxieties prompted an intensified awareness of the finiteness of time and the need to use one’s time wisely.

Often Victorian diaries contain apologias for missed entries and confessions of moral transgressions

Beatrice Webb (1858-1943), the pioneering socialist and co-founder of the London School of Economics, used her diary to record her attempts at self-education in psychology, philosophy and sociology. The eighth child of a wealthy businessman, as a young woman Beatrice frequently worried that she was wasting her time – and, thus, her life. In a typical diary entry, on 30 April 1883 she lamented: ‘the time rushes and I accomplish nothing,’ and later in June that year she confessed: ‘Wretchedly wasted week. No hard work done. Sick headache from over-eating and under-exercising.’

The pressure to achieve self-mastery and constantly improve could create a sense of continual failure – a sentiment many of us share with our Victorian forebears. As Steinitz wryly notes: ‘if one reached the goal of the fully improved, disciplined, controlled self, there would be no reason to write the self-improving, disciplining, controlling diary.’ Diarists were often unable to sustain the discipline of daily entries, especially those who favoured longer, descriptive entries, so they occasionally produced retrospective entries to maintain the illusion that they wrote daily. Often Victorian diaries are a record of failure, containing apologias for missed entries and confessions of moral transgressions. In 1852, the teenage Nunns recorded his many unauthorised absences from the chapel at Marlborough. Gladstone interpreted his daughter Agnes’s illness in September 1847 as the will of God but criticised his own failure to accept it, commenting that ‘everyone behaves well but me’. His ‘rescue work’ with prostitutes and intense struggles with the temptations of pornography and infidelity are constant preoccupations after 1840. As his biographer H C G Matthew wrote in 1988, these meetings with sex workers ‘became not merely a duty but a craving … an exposure to sexual stimulation which Gladstone felt he must both undergo and overcome.’ Diaries reveal the weaknesses, vices, doubts and insecurities that plagued 19th-century writers as they ultimately failed to live up to contemporary ideals of industry, piety, respectability and progress.

Nineteenth-century diaries show a growing middle class engaged in a constant quest for self-mastery and productivity. With the invention of printed commercial diaries came a new way of looking at life and new organisational possibilities. The future could be mapped out, goal-oriented, solution-focused. The Victorians were great innovators, but progress was Janus-faced. For every leap forward, a renewed pressure to go further, and faster, to do better, be better. The age of progress was also an age of anxiety.

While the Victorian diary might initially seem strange to us – the lists of books read, the constant references to religion, the fact that family members and spouses would exchange these private texts – contemporary social media accounts display the same tendencies towards performative self-improvement. In fact, the cultural obsession with self-improvement and ‘habit-tracking’ has intensified. Technology companies have successfully monetised this deep-rooted urge to better ourselves, providing new ways to document and compare our daily lives, which can create a perpetual sense of failure. The act of sharing stories about ourselves is no longer confined to a trusted circle of intimate friends and relatives. Instead, social media platforms function as multimedia diaries with an immediate, global audience who provide constant feedback on our choices and activities. As technology continues to improve our ability to mark and measure our own progress, we should learn from the Victorians and their diaries and ask ourselves: are we actually improving our lives or just finding new ways to criticise ourselves?